The Integration of the Volga Germans Into American Lutheranism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Directory of Minorities

World Directory of Minorities Europe MRG Directory –> Russian Federation –> Russian or Volga Germans Print Page Close Window Russian or Volga Germans Profile According to the 2002 national census, there are 597,212 Russian or Volga Germans in the Russian Federation. Volga Germans are primarily Lutheran and Mennonite in religion. Their number has fallen by almost half since 1989, as many have taken advantage of naturalization opportunities in Germany. Historical context Large-scale German settlement in Russia first occurred in the sixteenth century following Catherine the Great's decree of 1763 granting steppe land along the Volga River to Germans. In 1924 the Soviet regime created the Volga German ASSR with German as its official language. The republic was disbanded during the war and its German population (895,637) deported to Siberia and Central Asia. The Germans were not allowed to resettle in the region despite being rehabilitated in 1965. They settled instead in Siberia, the Ural mountains and the republics of Central Asia, especially Kazakhstan. From the late 1980s, a number of German organizations were established: Revival (Wiedergeburt, Vozrozhdenie); Freedom (Freiheit, Svoboda); and the Interstate Organization of Russian Germans (Zwischenstaathischer Verein der Russlanddeutschen). These organizations have campaigned for the restoration of their homeland but have faced strong opposition from the local populations of the Saratov and Volgograd oblasts. The German Government has allocated significant funds for the creation of German cultural centres and schools in Central Asia and Russia. This has not, however, deterred hundreds of thousands of Germans from emigrating to Germany. Ethnic Germans, their spouses and their descendants have been able to naturalize as German citizens through the Law of Return, in spite of often lacking even rudimentary knowledge of the German language. -

Prelims Nov 2005.Qxd

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 27 2005 Nr. 2 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. CLARISSA CAMPBELL ORR (ed.), Queenship in Europe 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), xvii + 419 pp. ISBN 0 521 81422 7. £60.00 ($100.00) During the past decade the literature on women at the European courts has grown rapidly. Queenship in Europe 1660–1815 is a wel- come addition to this expanding field of research and it appears as a natural extension of Clarissa Campbell Orr’s previous volume enti- tled Queenship in Britain, 1660–1837 (2002). Queenship in Europe consists of a fine introduction by the editor and fourteen essays on various consorts and/or mistresses. After a brief overview of the volume, this review will focus on Campell Orr’s introduction and a few selected papers that exemplify the strengths of the collection and reveal some of the difficulties that arise when court history is combined with gender history. In the first essay, Robert Oresko traces the life of the powerful Maria Giovanna Battista of Savoy-Nemours (1644–1724) with an emphasis on her regency and her extensive building projects. -

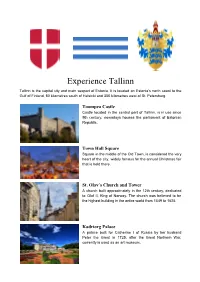

ExperienceTallinn

Experience Tallinn Tallinn is the capital city and main seaport of Estonia. It is located on Estonia's north coast to the Gulf of Finland, 80 kilometres south of H elsinki and 350 kilometres w est of S t. P etersburg. Toompea C astle Castle located in the central part of Tallinn, is in use since 9th century, nowadays houses the parliament of Estonian Republic. Town H all Square Square in the middle of the Old Town, is considered the very heart of the city, widely famous for the annual Christmas fair that is held there. St. O lav’s C hurch and T ower A church built approximately in the 12th century, dedicated to Olaf II, King of Norway. The church was believed to be the highest building in the entire w orld from 1549 to 1625. Kadriorg Palace A palace built for Catherine I of Russia by her husband Peter the Great in 1725, after the Great Northern War, currently is used as an art m useum. Town H all Pharmacy A pharmacy located on the Town Hall Square, which has been working continuosly since 14th century. Even nowadays one can buy any medicin needed from the pharmacy. Contains a little exhibition of different items used to treat diseases in the M iddle ages. St. A lexander N evsky C athedral The large and richly decorated Russian Orthodox church, designed in a mixed historicist style, was completed on Toompea Hill in 1900, when Estonia was part of the Czarist Empire. -

American Historical Society of Germans from Russia

Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia Winter 2019 Volume 42, No. 4 Editor, Michael Brown Emeritus Professor, University of Wyoming Editorial & Publications Coordinator, Allison Hunter-Frederick AHSGR Headquarters, Lincoln, Nebraska EDITORIAL BOARD Michael Brown Timothy J. Kloberdanz Emeritus Professor, University of Wyoming Professor Emeritus North Dakota State University, Laramie, WY Fargo, ND Robert Chesney J. Otto Pohl Cedarburg, Wisconsin Laguna Woods, CA Irmgard Hein Ellingson Dona Reeves Marquardt Bukovina Society, Ellis, KA Arofessor Emerita at Texas State University Austin, TX Velma Jesser Retired Educator Eric J. Schmaltz Calico Consulting, Las Cruces, NM Northwestern Oklahoma State University Alva, OK William Keel University of Kansas, Lawrence, KA Jerome Siebert Moraga, California Mission Statements The American Historical Society of Germans from Russia is an international organization whose mission is to discover, collect, perserve, and share the history, cultural heritage, and genealogical legacy of German settlers in the Russian Empire. The International Foundation of American Historical Society of Germans from Russia is responsible for exercising financial stewardship to generate, manage, and allocate resources which advance the mission and assist in securing the future of AHSGR. Cover Illustration Catholic church in the Village of Obermonjou. Photo provided by Olga Litzenburg. To learn more, see page 1. Contents Christmas in the German Villages on the Volga—and a Special Christmas Carol By Richard -

Russian Art, Icons + Antiques

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES International auction 872 1401 - 1580 RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. -

American Historical Society of Germans from Russia

American Historical Society Of Germans From Russia Kongregational Gemeinden von Amerika 61. Jahrgang Yankton, S. Dak. 14. January 1943 Nr. 11 Work Paper No. 6 May 1971 (front cover of WP6) TABLE OF CONTENTS President's Letter…………………………………………………………………….1 From the Editor's Desk…………………………………………………..3 Report From Germany ..Emma S. Haynes……………………………...4 Russia Revisited ...Cornelius Krahn………………………………….15 Comments on Frank ..Fred Grosskopf ……………………………….24 St. Joseph's Colonie, Balgonie .. A. Becker…………………………...25 Migration of the First Russian-Germans to The United States ..Friedrich Mutschelnaus Edited and Translated by Sen. Theodore Wenzlaff ……………………43 Inland Empire Russia Germans ..Harm H. Schlomer…………………..53 Genealogy Section ..Gerda Walker………………………………61 About the Cover: This photograph of the Church at Frank was donated by Mrs. Rachel Amen. It appeared in a publication of the Evangelical Congregational Conference. A comment on the picture is found on page 24. AMERICAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF GERMANS FROM RUSSIA POST OFFICE BOX 1424 GREELEY. COLORADO 80631 (inside front cover of WP6) American Historical Society of Germans from Russia 1004A NINTH AVENUE - P.O. BOX 1424 TELEPHONE; 352-9467 GREEL.EY. COLORADO 00631 April 27, 1971 OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS: H. J. Amen, President Emeritus 601 D Street Lincoln, Nebraska 68502 PRESIDENT'S LETTER Dr. Karl Stumpp, Chairman Emeritus 74 Tuebingen Autenrieth Strasse 16 West Germany David J. Miller, President Dear Members of AHSGR: P.O. Box 1424 Greeley, Colorado 80631 John H. Werner, Vice-President 522 Tucson The progress we have made in membership and in Aurora, Colorado 80010 contributions to our cause is proof of the basic need and W. F. Urbach. Vice-President 9320 East Center Avenue demand for AHSGR. -

TSARINA Ellen Alpsten

Book Club Guide TSARINA Ellen Alpsten In brief Lover, murder, mother, Tsarina. Memoirs of a Geisha meets Game of Thrones in this page-turning epic charting the extraordinary rags-to-riches tale of the most powerful woman history ever forgot. In detail Spring 1699: Illegitimate, destitute and strikingly beautiful, Marta has survived the brutal Russian winter in her remote Baltic village. Sold by her family into household labour at the age of fifteen, Marta survives by committing a crime that will force her to go on the run. A world away, Russia's young ruler, Tsar Peter I, passionate and iron-willed, has a vision for transforming the traditionalist Tsardom of Russia into a modern, Western empire. Countless lives will be lost in the process. Falling prey to the Great Northern War, Marta cheats death at every turn, finding work as a washerwoman at a battle camp. One night at a celebration, she encounters Peter the Great. Relying on her wits and her formidable courage, and fuelled by ambition, desire and the sheer will to live, Marta will become Catherine I of Russia. But her rise to the top is ridden with peril; how long will she survive the machinations of Peter's court, and more importantly, Peter himself? Author Biography Ellen Alpsten was raised in Kenya. She won the Grande École short story competition for her novella Meeting Mr Gandhi while studying for her Msc in PPE, and went on to work as a producer and presenter for Bloomberg TV in London. She has written for Vogue and Conde Nast Traveller. -

American Historical Society of Germans from Russia

Journal of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia Fall 2019 Volume 42, No. 3 Editor, Robert Meininger Professor Emeritus, Nebraska Wesleyan University Editorial & Publications Coordinator, Allison Hunter-Frederick AHSGR Headquarters, Lincoln, Nebraska Editorial Board Irmgard Hein Ellingson Timothy J. Kloberdanz, Professor Emeritus Bukovina Society, Ellis, KA North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND Velma Jesser, Retired Educator Eric J. Schmaltz Calico Consulting, Las Cruces, NM Northwestern Oklahoma State University, Alva, OK William Keel University of Kansas, Lawrence, KA MISSION STATEMENTS The American Historical Society of Germans from Russia is an international organization whose mission is to discover, collect, perserve, and share the history, cultural heritage, and genealogical legacy of German settlers in the Russian Empire. The International Foundation of American Historical Society of Germans from Russia is responsible for exercising financial stewardship to generate, manage, and allocate resources which advance the mission and assist in securing the future of AHSGR. Cover Illustration A Lutheran church in the Village of Jost. Photo provided by Olga Litzenburg. To learn more, see page 1. Contents Jost (Jost, Obernberg, Popovkina, Popovkino; no longer existing) By Dr. Olga Litzenberger....................................................................................................................................1 Maternal Instincts By Christine Antinori ..........................................................................................................................................7 -

American Historical Society of Germans from Russia

American Historical Society Of Germans From Russia Work Paper No. 25 Winter, 1977 Price $2.50 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE RuthM. Amen ................................…………………………………………………………...............…................... i TWO POEMS Nona Uhrich Nimnicht .................................…………………………………………………………….........……............... .ii PASSAGE TO RUSSIA: WHO WERE THE EMIGRANTS? Lew Malinowski Translated by Dona B. Reeves. ................………………………………….................……................ 1 THE FIRST STATISTICAL REPORT ON THE VOLGA COLONIES - February 14, 1769. Prepared for Empress Catherine II by Count Orlov Translated by Adam Giesinger.....................................……………………………………………………………...............…4 EARLY CHRONICLERS AMONG THE VOLGA GERMANS Reminiscences ofHeinrich Erfurth, S. Koliweck, and Kaspar Scheck Translated by Adam Giesinger. ...............................……………………………………………………..................... 10 A VOLHYNIAN GERMAN CONTRACT Adam Giesinger. ...................................................…………………………………………………………............. 13 THE REBUILDING OF GERMAN EVANGELICAL PARISHES IN THE EAST An Appeal of 17 January 1943 to the Nazi authorities by Pastor Friedrich Rink Translated by Adam Giesinger. ..................................……………………………………………………................... 15 A BIT OF EUROPE IN DAKOTA: THE GERMAN RUSSIAN COLONY AT EUREKA W. S. Harwood ..........................................…………………………………………………………….................... .17 A VOICE FROM THE PAST: The Autobiography of Gottlieb Isaak Introduced -

Little Russia: Patterns in Migration, Settlement, and the Articulation of Ethnic Identity Among Portland's Volga Germans

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-12-2018 Little Russia: Patterns in Migration, Settlement, and the Articulation of Ethnic Identity Among Portland's Volga Germans Heather Ann Viets Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Viets, Heather Ann, "Little Russia: Patterns in Migration, Settlement, and the Articulation of Ethnic Identity Among Portland's Volga Germans" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4440. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6324 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Little Russia: Patterns in Migration, Settlement, and the Articulation of Ethnic Identity Among Portland’s Volga Germans by Heather Ann Viets A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Katrine Barber, Chair Marc Rodriguez Tim Garrison Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Heather Ann Viets Abstract The Volga Germans assert a particular ethnic identity to articulate their complex history as a multinational community even in the absence of traditional practices in language, religious piety, and communal lifestyle. Across multiple migrations and settlements from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, the Volga Germans’ self- constructed group identity served historically as a tool with which to navigate uncertain politics of belonging. -

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including the Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection

RUSSIAN ART, ICONS + ANTIQUES Including The Commercial Attaché Richard Zeiner-Henriksen Russian Collection International auction 872 AUCTION Friday 9 June 2017, 2 pm PREVIEW Wednesday 24 May 3 pm - 6 pm Thursday 25 May Public Holiday Friday 26 May 11 am - 5 pm Saturday 27 May 11 am - 4 pm Sunday 28 May 11 am - 4 pm Monday 29 May 11 am - 5 pm or by appointment Bredgade 33 · DK-1260 Copenhagen K · Tel +45 8818 1111 · Fax +45 8818 1112 [email protected] · bruun-rasmussen.com 872_russisk_s001-188.indd 1 28/04/17 16.28 Коллекция коммерческого атташе Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена и другие русские шедевры В течение 19 века Россия переживала стремительную трансформацию - бушевала индустриализация, модернизировалось сельское хозяйство, расширялась инфраструктура и создавалась обширная телеграфная система. Это представило новые возможности для международных деловых отношений, и известные компании, такие как датская Бурмэйстер энд Вэйн (В&W), Восточно-Азиатская Компания (EAC) и Компания Грэйт Норсерн Телеграф (GNT) открыли офисы в России и внесли свой вклад в развитие страны. Большое количество скандинавов выехало на Восток в поисках своей удачи в растущей деловой жизни и промышленности России. Среди многочисленных путешественников возникало сильное увлечение культурой страны, что привело к созданию высококачественных коллекций русского искусства. Именно по этой причине сегодня в Скандинавии так много предметов русского антиквариата, некоторые из которых будут выставлены на этом аукционе. Самые значимые из них будут ещё до аукциона выставлены в посольстве Дании в Лондоне во время «Недели Русского Искусства». Для более подробной информации смотри страницу 9. Изюминкой аукциона, без сомнения, станет Русская коллекция Ричарда Зейнера-Хенриксена, норвежского коммерческого атташе. Мы представляем эту коллекцию в сотрудничестве с норвежским аукционным домом Бломквист (Blomqvist Kunsthandel AS) в Осло. -

Domesticating the German East: Nazi Propaganda and Women's Roles in the “Germanization” of the Warthegau During World Wa

DOMESTICATING THE GERMAN EAST: NAZI PROPAGANDA AND WOMEN’S ROLES IN THE “GERMANIZATION” OF THE WARTHEGAU DURING WORLD WAR II Madeline James A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the History Department in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Konrad Jarausch Karen Auerbach Karen Hagemann © 2020 Madeline James ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Madeline James: Domesticating the German East: Nazi Propaganda And Women’s Roles in the “Germanization” of the Warthegau during World War II (Under the direction of Konrad Jarausch and Karen Auerbach) This thesis utilizes Nazi women’s propaganda to explore the relationship between Nazi gender and racial ideology, particularly in relation to the Nazi Germanization program in the Warthegau during World War II. At the heart of this study is an examination of a paradox inherent in Nazi gender ideology, which simultaneously limited and expanded “Aryan” German women’s roles in the greater German community. Far from being “returned to the home” by the Nazis in 1933, German women experienced an expanded sphere of influence both within and beyond the borders of the Reich due to their social and cultural roles as “mothers of the nation.” As “bearers of German culture,” German women came to occupy a significant role in Nazi plans to create a new “German homeland” in Eastern Europe. This female role of “domesticating” the East, opposite the perceived “male” tasks of occupation, expulsion, and resettlement, entailed cultivating and reinforcing Germanness in the Volksdeutsche (ethnic German) communities, molding them into “future masters of the German East.” This thesis therefore also examines the ways in which Reich German women utilized the notion of a distinctly female cultural sphere to stake a claim in the Germanizing mission.