Vyasa's Draupadi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

Introduction to BI-Tagavad-Gita

TEAcI-tER'S GuidE TO INTROduCTioN TO BI-tAGAVAd-GiTA (DAModAR CLASS) INTROduCTioN TO BHAqAVAd-qiTA Compiled by: Tapasvini devi dasi Hare Krishna Sunday School Program is sponsored by: ISKCON Foundation Contents Chapter Page Introduction 1 1. History ofthe Kuru Dynasty 3 2. Birth ofthe Pandavas 10 3. The Pandavas Move to Hastinapura 16 4. Indraprastha 22 5. Life in Exile 29 6. Preparing for Battle 34 7. Quiz 41 Crossword Puzzle Answer Key 45 Worksheets 46 9ntroduction "Introduction to Bhagavad Gita" is a session that deals with the history ofthe Pandavas. It is not meant to be a study ofthe Mahabharat. That could be studied for an entire year or more. This booklet is limited to the important events which led up to the battle ofKurlLkshetra. We speak often in our classes ofKrishna and the Bhagavad Gita and the Battle ofKurukshetra. But for the new student, or student llnfamiliar with the history ofthe Pandavas, these topics don't have much significance ifthey fail to understand the reasons behind the Bhagavad Gita being spoken (on a battlefield, yet!). This session will provide the background needed for children to go on to explore the teachulgs ofBhagavad Gita. You may have a classroonl filled with childrel1 who know these events well. Or you may have a class who has never heard ofthe Pandavas. You will likely have some ofeach. The way you teach your class should be determined from what the children already know. Students familiar with Mahabharat can absorb many more details and adventures. Young children and children new to the subject should learn the basics well. -

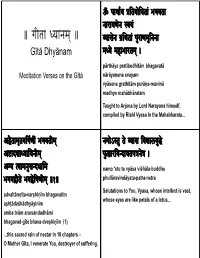

Microsoft Powerpoint

ॐ पाथाय ितबाधताे भगवता नारायणने वय ꠱ गीतॎ यॎनम् ꠱ यासेन थता पराणमिननापराणमु ुिनना Gītā Dhyānam मये महाभारतम् ꠰ pārthāya pratibodhitām bhagavatā Meditation Verses on the Gītā nārāyaṇena svayam vyāsena grathitām purāṇa-muninā madhyemahābhāratam Taught to Arjuna by Lord Narayana himself, compiled by Rishi Vyasa in the Mahabharata... अैतामतवषृ णी भगवतीम् नमाऽते त े यास वशालबु े अादशायाीयनीम् फु ारवदायतपन꠰ेे अब वामनसदधामवामनसदधामु namo 'stu te vyāsa viśhāla-buddhe phullāravindāyata-patra-netra भगवत े भवभवषणीमेषणीम् ꠱१꠱ Salutations to You, Vyyasa, whose intellect is vast, advaitāmṛita-varṣhiṇīm bhagavatīm whose eyes are like petals of a lotus... aṣhṭādaśhādhyāyinīm amba tvām anusandadhāmi bhagavad-gīte bhava-dveṣhiṇīm (1) ...this sacred rain of nectar in 18 chapters – O Mother Gita, I venerate You, destroyer of suffering. येन वया भारततलपै ूण पपारजाताय तावे े कपाणयै े꠰ वालता ेे ानमय दप ꠱२꠱ ानमु य कृ णाय गीतामृतदहु ेे नम ꠱३꠱ yena tvayā bhārata-taila-pūrṇaḥ prapanna-pārijātāya prajvālito jñāna-mayaḥ pradīpaḥ (2) totra-vetraika-pāṇaye jñāna-mudrāya kṛiṣhṇāya ...by whom the lamp filled with the oil of the gītāmṛita-dhduhenamaḥ (3) Mahabharata was lit with the flame of knowledge. Salutations to Krishna , who blesses the surrendered, in whose hands are a staff and the symbol of knowledge, who milks the Gita's nectar. सवापिनषदाे े गावा े दाधाे गापालनदने ꠰ वसदेवसत देव क सचाणरमदू नम꠰् पाथा े वस सध ीभााेे दधु गीतामृत महत् ꠰꠰ देेवकपरमानद कृ ण वदेे जगु म् ꠱꠱ sarvopaniṣhado gāvo vasudeva-sutam devam dogdhā gopāla-nandanaḥ kaḿsa-cāṇūra-mardanam pārtho vatsaḥ sudhīr bhoktā devakī-paramānandam ddhdugdham gītāmṛitam mahthat (4) kṛiṣhṇam vande jdjagad-gurum (5) The Upanishads are cows, Krishna is the cowherd, I revere Sri Krishna, teacher of all, son of Vasudeva, Arjuna is the calf, and wise people enjoy the sacred destroyer of Kamsa and Chanura, who is the delight nectar milked from the Gita. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

Dr Anupama.Pdf

NJESR/July 2021/ Vol-2/Issue-7 E-ISSN-2582-5836 DOI - 10.53571/NJESR.2021.2.7.81-91 WOMEN AND SAMSKRIT LITERATURE DR. ANUPAMA B ASSISTANT PROFESSOR (VYAKARNA SHASTRA) KARNATAKA SAMSKRIT UNIVERSITY BENGALURU-560018 THE FIVE FEMALE SOULS OF " MAHABHARATA" The Mahabharata which has The epics which talks about tradition, culture, laws more than it talks about the human life and the characteristics of male and female which most relevant to this modern period. In Indian literature tradition the Ramayana and the Mahabharata authors talks not only about male characters they designed each and every Female characters with most Beautiful feminine characters which talk about their importance and dutiful nature and they are all well in decision takers and live their lives according to their decisions. They are the most powerful and strong and also reason for the whole Mahabharata which Occur. The five women in particular who's decision makes the whole Mahabharata to happen are The GANGA, SATYAVATI, AMBA, KUNTI and DRUPADI. GANGA: When king shantanu saw Ganga he totally fell for her and said "You must certainly become my wife, whoever you may be." Thus said the great King Santanu to the goddess Ganga who stood before him in human form, intoxicating his senses with her superhuman loveliness 81 www.njesr.com The king earnestly offered for her love his kingdom, his wealth, his all, his very life. Ganga replied: "O king, I shall become your wife. But on certain conditions that neither you nor anyone else should ever ask me who I am, or whence I come. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

Understanding Draupadi As a Paragon of Gender and Resistance

start page: 477 Stellenbosch eological Journal 2017, Vol 3, No 2, 477–492 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2017.v3n2.a22 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2017 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Understanding Draupadi as a paragon of gender and resistance Motswapong, Pulane Elizabeth University of Botswana [email protected] Abstract In this article Draupadi will be presented not only as an unsung heroine in the Hindu epic Mahabharata but also as a paragon of gender and resistance in the wake of the injustices meted out on her. It is her ability to overcome adversity in a venerable manner that sets her apart from other women. As a result Draupadi becomes the most complex and controversial female character in the Hindu literature. On the one hand she could be womanly, compassionate and generous and on the other, she could wreak havoc on those who wronged her. She was never ready to compromise on either her rights as a daughter-in-law or even on the rights of the Pandavas, and remained ever ready to fight back or avenge with high handedness any injustices meted out to her. She can be termed a pioneer of feminism. The subversion theory will be employed to further the argument of the article. This article, will further illustrate how Draupadi in the midst of suffering managed to overcome the predicaments she faced and continue to strive where most women would have given up. Key words Draupadi; marriage; gender and resistance; Mahabharata and women 1. Introduction The heroine Draupadi had many names: she was called Draupadi from her father’s family; Krishnaa the dusky princess, Yajnaseni-born of sacrificial fire, Parshati from her grandfather side, panchali from her country; Sairindhiri, the maid servant of the queen Vitara, Panchami (having five husbands)and Nitayauvani,(the every young) (Kahlon 2011:533). -

Teachings of Queen Kunti Consists of Kunti's Celebrated Prayers As Recorded in the Srimad Bhagavatam Together with Illuminating Commen Tary by His Divine Grace A

lfisDivine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada FOUNDER-ACARYA OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS THE TRAGIC and heroic figure of Queen Kunti emerges &om an explosive era in the history of ancient India. As the wife of King Pal)QU and the mother of five illustrious sons (the Pal)<,lavas), she was a central figure in a complex political drama that fifty centuries ago culminated in the devas tating Kuruk�etra War. At the conclusion of the war, Queen Kunti approaches Lord Knl)a as He prepares to depart &om the scene of battle. Although Kunti is Lord Knl)a's aunt (He incarnated as her brother Vasudeva's son), she perfectly understands His exalted and divine identity as the Supreme Per sonality of Godhead. She knows full well that He descended from His abode in the spiritual world to rid the earth of demoniac military forces and reestablish peace and righteousness. Thus the prayers she offers Him on this occasion are not the conventional pious solicitations. Rather, they are philosophical reSections, devotional illumina tions, even mystical exultations. As such they have been recorded and immortalized in the Srimad-Bhagavatam, India's greatest philosophical and spiritual classic. Queen Kunti's prayers-the simple and il luminating outpourings of the soul of a great and saintly woman devotee-reveal both the deepest transcendental emotions of the heart and the most profound philosophical and theological penetra tions of the intellect. Her words have been recited, chanted, and sung by sages and philoso phers in India for thousands of years. Teachings of Queen Kunti consists of Kunti's celebrated prayers as recorded in the Srimad Bhagavatam together with illuminating commen tary by His Divine Grace A. -

Dharma As a Consequentialism the Threat of Hridayananda Das Goswami’S Consequentialist Moral Philosophy to ISKCON’S Spiritual Identity

Dharma as a Consequentialism The threat of Hridayananda das Goswami’s consequentialist moral philosophy to ISKCON’s spiritual identity. Krishna-kirti das 3/24/2014 This paper shows that Hridayananda Das Goswami’s recent statements that question the validity of certain narrations in authorized Vedic scriptures, and which have been accepted by Srila Prabhupada and other acharyas, arise from a moral philosophy called consequentialism. In a 2005 paper titled “Vaisnava Moral Theology and Homosexuality,” Maharaja explains his conception consequentialist moral reasoning in detail. His application of it results in a total repudiation of Srila Prabhupada’s authority, a repudiation of several acharyas in ISKCON’s parampara, and an increase in the numbers of devotees whose Krishna consciousness depends on the repudiation of these acharyas’ authority. A non- consequentialist defense of Śrīla Prabhupāda is presented along with recommendations for resolving the existential threat Maharaja’s moral reasoning poses to the spiritual well-being of ISKCON’s members, the integrity of ISKCON itself, and the authenticity of Srila Prabhupada’s spiritual legacy. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Dharma as a Consequentialism ..................................................................................................................... 1 Maharaja’s application of consequentialism to Krishna Consciousness ..................................................... -

A Comprehensive Guide by Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts

A Comprehensive Guide By Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts: Mahabharata ● Written by Vyasa ● Its plot centers on the power struggle between the Kaurava and Pandava princes. They fight the Kurukshetra War for the throne of Hastinapura, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan. ● As per legend, Vyasa dictates it to Ganesha, who writes it down ● Divided into 18 parvas and 100 subparvas ● The Mahabharata is told in the form of a frame tale. Janamejaya, an ancestor of the Pandavas, is told the tale of his ancestors while he is performing a snake sacrifice ● The Genealogy of the Kuru clan ○ King Shantanu is an ancestor of Kuru and is the first king mentioned ○ He marries the goddess Ganga and has the son Bhishma ○ He then wishes to marry Satyavati, the daughter of a fisherman ○ However, Satyavati’s father will only let her marry Shantanu on one condition: Shantanu must promise that any sons of Satyavati will rule Hastinapura ○ To help his father be able to marry Satyavati, Bhishma renounces his claim to the throne and takes a vow of celibacy ○ Satyavati had married Parashara and had a son with him, Vyasa ○ Now she marries Shantanu and has another two sons, Chitrangada and Vichitravirya ○ Shantanu dies, and Chitrangada becomes king ○ Chitrangada lives a short and uneventful life, and then dies, making Vichitravirya king ○ The King of Kasi puts his three daughters up for marriage (A swayamvara), but he does not invite Vichitravirya as a possible suitor ○ Bhishma, to arrange a marriage for Vichitravirya, abducts the three daughters of Kasi: Amba, -

Dharma in the Mahabharata As a Response to Ecological Crises: a Speculation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Trumpeter - Journal of Ecosophy (Athabasca University) Dharma in the Mahabharata as a response to Ecological Crises: A speculation By Kamesh Aiyer Abstract Without doing violence to Vyaasa, the Mahabharata (Vyaasa, The Mahabharata 1933-1966) can be properly viewed through an ecological prism, as a story of how “Dharma” came to be established as a result of a conflict over social policies in response to on-going environmental/ecological crises. In this version, the first to recognize the crises and to attempt to address them was Santanu, King of Hastinapur (a town established on the banks of the Ganges). His initial proposals evoked much opposition because draconian and oppressive, and were rescinded after his death. Subsequently, one of Santanu’s grandsons, Pandu, and his children, the Pandavas, agreed with Santanu that the crises had to be addressed and proposed more acceptable social policies and practices. Santanu’s other grandson, Dhritarashtra, and his children, the Kauravas, disagreed, believing that nothing needed to be done and opposed the proposed policies. The fight to establish these policies culminated in the extended and widespread “Great War” (the “Mahaa-Bhaarata”) that was won by the Pandavas. Some of the proposed practices/social policies became core elements of "Hinduism" (such as cow protection and caste), while others became accepted elements of the cultural landscape (acceptance of the rights of tribes to forests as “commons”). Still other proposals may have been implied but never became widespread (polyandry) or may have been deemed unacceptable and immoral (infanticide). -

Always Remember Krishna - Part 10

Always Remember Krishna - Part 10 Date: 2014-09-27 Author: Sudarshana devi dasi Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis, Please accept my humble obeisances! All glories to Srila Prabhupada and Srila Gurudev! This is in continuation of the previous offerings titled, "Always Remember Krishna" wherein we were meditating on Arjuna's experiences once Krishna returned to Goloka. In previous offerings we meditated on the 8 blessings recollected by Arjuna. Now we shall continue to hear further. d. Blessing 9: In Srimad Bhagavatam verse 1.15.16 Arjuna says, yad-doḥṣu mā praṇihitaṁ guru-bhīṣma-karṇa- naptṛ-trigarta-śalya-saindhava-bāhlikādyaiḥ astrāṇy amogha-mahimāni nirūpitāni nopaspṛśur nṛhari-dāsam ivāsurāṇi Great generals like Bhishma, Drona, Karna, Bhurishrava, Susharma, Shalya, Jayadratha, and Bahlika all directed their invincible weapons against me. But by His [Lord Krishna's] grace they could not even touch a hair on my head. Similarly, Prahlada Maharaja, the supreme devotee of Lord Narsimhadeva, was unaffected by the weapons the demons used against him. In Kurukshetra war, there were so many dangerous situations faced by Arjuna when he had to fight against great generals like Bhishma, Drona, Karna etc. who had many powerful weapons which when released on Arjuna would have definitely caused death. But in every instance Krishna protected him. In case of Bhishmadev we know how Duryodhana blamed him to be partial to Pandavas and hurt by Duryodhana's lack of trust, Bhishmadev reserved five special arrows, one for each of the Pandavas. That night, somehow Krishna inspired Arjuna and took away those arrows Bhishmadev had reserved to kill the Pandavas.