Dharma As a Consequentialism the Threat of Hridayananda Das Goswami’S Consequentialist Moral Philosophy to ISKCON’S Spiritual Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to BI-Tagavad-Gita

TEAcI-tER'S GuidE TO INTROduCTioN TO BI-tAGAVAd-GiTA (DAModAR CLASS) INTROduCTioN TO BHAqAVAd-qiTA Compiled by: Tapasvini devi dasi Hare Krishna Sunday School Program is sponsored by: ISKCON Foundation Contents Chapter Page Introduction 1 1. History ofthe Kuru Dynasty 3 2. Birth ofthe Pandavas 10 3. The Pandavas Move to Hastinapura 16 4. Indraprastha 22 5. Life in Exile 29 6. Preparing for Battle 34 7. Quiz 41 Crossword Puzzle Answer Key 45 Worksheets 46 9ntroduction "Introduction to Bhagavad Gita" is a session that deals with the history ofthe Pandavas. It is not meant to be a study ofthe Mahabharat. That could be studied for an entire year or more. This booklet is limited to the important events which led up to the battle ofKurlLkshetra. We speak often in our classes ofKrishna and the Bhagavad Gita and the Battle ofKurukshetra. But for the new student, or student llnfamiliar with the history ofthe Pandavas, these topics don't have much significance ifthey fail to understand the reasons behind the Bhagavad Gita being spoken (on a battlefield, yet!). This session will provide the background needed for children to go on to explore the teachulgs ofBhagavad Gita. You may have a classroonl filled with childrel1 who know these events well. Or you may have a class who has never heard ofthe Pandavas. You will likely have some ofeach. The way you teach your class should be determined from what the children already know. Students familiar with Mahabharat can absorb many more details and adventures. Young children and children new to the subject should learn the basics well. -

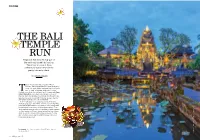

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Understanding Draupadi As a Paragon of Gender and Resistance

start page: 477 Stellenbosch eological Journal 2017, Vol 3, No 2, 477–492 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2017.v3n2.a22 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2017 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Understanding Draupadi as a paragon of gender and resistance Motswapong, Pulane Elizabeth University of Botswana [email protected] Abstract In this article Draupadi will be presented not only as an unsung heroine in the Hindu epic Mahabharata but also as a paragon of gender and resistance in the wake of the injustices meted out on her. It is her ability to overcome adversity in a venerable manner that sets her apart from other women. As a result Draupadi becomes the most complex and controversial female character in the Hindu literature. On the one hand she could be womanly, compassionate and generous and on the other, she could wreak havoc on those who wronged her. She was never ready to compromise on either her rights as a daughter-in-law or even on the rights of the Pandavas, and remained ever ready to fight back or avenge with high handedness any injustices meted out to her. She can be termed a pioneer of feminism. The subversion theory will be employed to further the argument of the article. This article, will further illustrate how Draupadi in the midst of suffering managed to overcome the predicaments she faced and continue to strive where most women would have given up. Key words Draupadi; marriage; gender and resistance; Mahabharata and women 1. Introduction The heroine Draupadi had many names: she was called Draupadi from her father’s family; Krishnaa the dusky princess, Yajnaseni-born of sacrificial fire, Parshati from her grandfather side, panchali from her country; Sairindhiri, the maid servant of the queen Vitara, Panchami (having five husbands)and Nitayauvani,(the every young) (Kahlon 2011:533). -

Teachings of Lord Kapila” by His Divine Grace A.C

“Teachings of Lord Kapila” by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This is an evaluation copy of the printed version of this book, and is NOT FOR RESALE. This evaluation copy is intended for personal non-commercial use only, under the “fair use” guidelines established by international copyright laws. You may use this electronic file to evaluate the printed version of this book, for your own private use, or for short excerpts used in academic works, research, student papers, presentations, and the like. You can distribute this evaluation copy to others over the Internet, so long as you keep this copyright information intact. You may not reproduce more than ten percent (10%) of this book in any media without the express written permission from the copyright holders. Reference any excerpts in the following way: “Excerpted from “Teachings of Lord Kapila” by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, courtesy of the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, www.Krishna.com .” This book and electronic file is Copyright 1977-2003 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, 3764 Watseka Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90034, USA. All rights reserved. For any questions, comments, correspondence, or to evaluate dozens of other books in this collection, visit the website of the publishers, www.Krishna.com . Foreword Kapila Muni, a renowned sage of antiquity, is the author of the philosophical system known as Sankhya, which forms an important part of lndia's ancient philosophical heritage. Sankhya is both a system of metaphysics, dealing with the elemental principles of the physical universe, and a system of spiritual knowledge, with its own methodology, culminating in full consciousness of the Supreme Absolute. -

Srila Prabhupada

About Srila Prabhupada His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada is the founder Acharya of ISKCON. He travelled to New York in 1965 at the age of 69, to spread the teachings of Lord Chaitanya. Srila Prabhupada visited Chennai in 1972 and 1975 and began the Chennai chapter of ISKCON. He specifically told his disciples to build a “gorgeous temple” in Chennai. His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada was born in 1896 in Calcutta, India. He first met his spiritual master, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Gosvami, in Calcutta in 1922. Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, a prominent devotional scholar and the founder of sixty-four branches of Gaudiya Mathas (Vedic institutes), liked this educated young man and convinced him to dedicate his life to teaching Vedic knowledge in the Western world. Srila Prabhupada became his student, and eleven years later (1933) at Allahabad, he became his formally initiated disciple. At their first meeting, in 1922, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura requested Srila Prabhupada to broadcast Vedic knowledge through the English language. In the years that followed, Srila Prabhupada wrote a commentary on the Bhagavad-gita and in 1944, without assistance, started an English fortnightly magazine. Recognizing Srila Prabhupada’s philosophical learning and devotion, the Gaudiya Vaisnava Society honored him in 1947 with the title “Bhaktivedanta.” In 1950, at the age of fifty-four, Srila Prabhupada retired from married life, and four years later he adopted the vanaprastha (retired) order to devote more time to his studies and writing. Srila Prabhupada traveled to the holy city of Vrndavana, where he lived in very humble circumstances in the historic medieval temple of Radha- Damodara. -

Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

S International Journal of Arts, Science and Humanities Karmic Philosophy and the Model of Disability in Ancient India OPEN ACCESS Neha Kumari Research Scholar, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India Volume: 7 Abstract Disability has been the inescapable part of human society from ancient times. With the thrust of Issue: 1 disability right movements and development in eld of disability studies, the mythical past of dis- ability is worthy to study. Classic Indian Scriptures mention differently able character in prominent positions. There is a faulty opinion about Indian mythology is that they associate disability chie y Month: July with evil characters. Hunch backed Manthara from Ramayana and limping legged Shakuni from Mahabharata are negatively stereotyped characters. This paper tries to analyze that these charac- ters were guided by their motives of revenge, loyalty and acted more as dramatic devices to bring Year: 2019 crucial changes in plot. The deities of lord Jagannath in Puri is worshipped , without limbs, neck and eye lids which ISSN: 2321-788X strengthens the notion that disability is an occasional but all binding phenomena in human civiliza- tion. The social model of disability brings forward the idea that the only disability is a bad attitude for the disabled as well as the society. In spite of his abilities Dhritrashtra did face discrimination Received: 31.05.2019 because of his blindness. The presence of characters like sage Ashtavakra and Vamanavtar of Lord Vishnu indicate that by efforts, bodily limitations can be transcended. Accepted: 25.06.2019 Keywords: Karma, Medical model, Social model, Ability, Gender, Charity, Rights. -

Most Intelligent Persons Would Go for Gauranga,All That You Have to Do Is

Most intelligent persons would go for Gauranga Speaker: HH Lokanath Swami Venue: Mayapur Candrodaya Mandir Date: 7 March 2016 So that’s the verse, Eleventh Canto, Chapter 5, Text 32. Are you familiar, if you have looked at the board? Yeah! Sounds familiar? Not new! But ever ever new also at the same time! Never be-comes old! So here we are in land of Gauranga, Gauranga! (Devotees respond: Gauranga!) Sri Krishna Cai-tanya Mahaprabhu ki (Devotees respond: Jaya!) And also we have gathered here amongst other reasons, gathered here for Kirtan Mela ki (Devotees respond: Jaya!) Yes, you have come here for Kirtan Mela! Some of you have just come for the Kirtan Mela.. So I thought of selecting a verse that talks of Caitanya Mahaprabhu as well as of course talks about the kirtana, sankirtana- yajna, that we are engaged in here. So quickly as time is running. krsna-varnam tvisakrsnam sangopangastra-parsadam yajnaih sankirtana-prayair yajanti hi su-medhasah ( SB 11.5.32) Translation and Purport by disciples of His Divine Grace A C Bhaktivedanta Swami Srila Prab-hupada ki (Devotees respond: Jaya!) “In the Age of Kali, intelligent persons perform congregational chanting to worship the incarnation of Godhead who constantly sings the names of Krsna. Although His complexion is not blackish, He is Krsna Himself. He is accompanied by His associates, servants, weapons and confidential companions.” “This same verse is quoted by Krsnadasa Kaviraja in the Caitanya-caritamrita, Adi-lila, Chapter Three, verse 52”. And I was reminded that Laghu Bhagavatamrta of Rupa Goswami, he also quotes this verse in the very beginning of Laghu Bhagavatamrta, Rupa Goswami does, its part of his mangalacarana, same verse. -

Inquiries Into the Absolute

Inquiries into the Absolute (A collection of thought provoking & intriguing answers given by His Holiness Romapada Swami for questions raised by devotees on various spiritual topics) Shri Shri Radha Govinda, Brooklyn, NY We invite you to immerse yourself into the transcendental answers given by Srila Romapada Swami! These sublime instructions are certain to break our misconceptions into millions of pieces and to deepen our understanding of various topics in Krishna consciousness. Compilation of weekly digests 1 to 242 (Upto December 2007) His Holiness Srila Romapada Swami Maharaj! Everyone one likes to inquire. Srila Prabhupada writes, "The whole world is full of questions and answers. The birds, beasts and men are all busy in the matter of perpetual questions and answers... Although they go on making such questions and answers for their whole lives, they are not at all satisfied. Satisfaction of the soul can only be obtained by questions and answers on the subject of Krishna." -- Purport to Srimad Bhagavatam 1.2.5 "Inquiries into the Absolute" is a wonderful opportunity provided by Srila Romapada Swami to help us fruitfully engage our propensity to inquire and seek answers. Please take advantage! Guide to “Inquiries into the Absolute” om ajïäna-timirändhasya jïänäïjana-çaläkayä cakñur unmélitaà yena tasmai çré-gurave namaù I offer my respectful obeisances unto my spiritual master, who has opened my eyes, blinded by the darkness of ignorance, with the torchlight of knowledge. ‘Inquiries into the Absolute’, is a weekly email digest comprising of thought provoking and sublime answers given by His Holiness Romapada Swami Maharaj to the questions raised by devotees on myriad spiritual topics. -

About Yajna, Yaga & Homa

Mahabharata Series About Yajna, Yaga & Homa Compiled by: G H Visweswara PREFACE I have extracted these contents from my other comprehensive & unique work on Mahabharata called Mahabharata-Spectroscope. (See http://www.ghvisweswara.com/mahabharata-2/mahabharata-spectroscope-a-unique- resource/). Whereas the material in that was included in the order in which it appears in the original epic, in this compilation I have grouped them by meaningful Topics & Sub- topics thus making it much more useful to the student/scholar of this subject. This is a brief compilation of the contents appearing in the great epic Mahabharata on the topics of Yajna, Yaga & Homa. The compilation is not exhaustive in the sense that every para appearing in the great epic is not included here for the sake of limiting the size of this document. Some of the topics like japa-yajna have already been compiled in another document called Japa-Dhayana-Pranayama. But still most of the key or representative passages have been compiled here. The contents are from Mahabharata excluding Bhagavad Gita. I hope the readers will find the document of some use in their study on these topics. Please see http://www.ghvisweswara.com/mahabharata-2 for my other topic based compilations based on Mahabharata. G H Visweswara [email protected] www.ghvisweswara.com March 2017 About Yajna, Yaga & Homa in Mahabharata: G H Visweswara Page 1 Table of Contents About Yajna, Yaga & Homa in Mahabharata .......................................................................................... 4 Eligibility, -

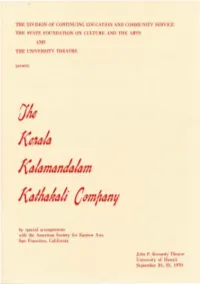

THE DIVISION of CONTINUING EDUCATION and COMMUNITY SERVICE the STATE FOUNDATION on CULTURE and the ARTS and the UNIVERSITY THEATRE Present

THE DIVISION OF CONTINUING EDUCATION AND COMMUNITY SERVICE THE STATE FOUNDATION ON CULTURE AND THE ARTS AND THE UNIVERSITY THEATRE present by special arrangements with the American Society for Eastern Arts San Francisco, California John F. Kennedy Theatre University of Hawaii September 24, 25, 1970 /(ala mania/am /(aiAahali Company The Kerala Kalamandalam (the Kerala State Academy of the Arts) was founded in 1930 by ~lahaka vi Vallathol, poet laureate of Kerala, to ensure the continuance of the best tradi tions in Kathakali. The institution is nO\\ supported by both State and Central Governments and trains most of the present-day Kathakali actors, musicians and make-up artists. The Kerala Kalamandalam Kathakali company i::; the finest in India. Such is the demand for its performances that there is seldom a "night off" during the performing season . Most of the principal actors are asatts (teachers) at the in::;titution. In 1967 the com pany first toured Europe, appearing at most of the summer festi vals, including Jean-Louis Barrault's Theatre des Nations and 15 performances at London's Saville Theatre, as well as at Expo '67 in Montreal. The next year, they we re featured at the Shiraz-Persepolis International Festival of the Arts in I ran. This August the Kerala Kalamandalam company performed at Expo '70 in Osaka and subsequently toured Indonesia, Australia and Fiji. This. their first visit to the Cnited States, is presented by the American Society for Eastern Arts. ACCOMPANISTS FOR BOTH PROGRAMS Singers: Neelakantan Nambissan S. Cangadharan -

Vishnu Sahasra Nama

Visnu-sahasra-nama Thousand Names of Lord Visnu (from Mahabharata, original translation and purports b y Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana) translated into English by Sriman Kusakratha das (ACBSP) Maëagläcaraëam (by Baladeva Vidyäbhüñaëa) Text 1 ananta kalyäëa-guëaika-väridhir vibhu-cid-änanda-ghano bhajat-priyaù kåñëas tri-çaktir bahu-mürtir éçvaro viçvaika-hetuù sa karotu naù çubham May Lord Kåñëa, the all-powerful Supreme Personality of Godhead, who appears in many forms, is the original creator of the universe, the master of the three potencies, full of transcendental knowledge and bliss, very dear to the devotees, and an ocean of unlimited auspicious qualities, grant auspiciousness to us. Text 2 vyäsaà satyavaté-sutaà muni-guruà näräyaëaà saàstumo vaiçampäyanam ucyatähvaya-sudhämodaà prapadyämahe gaìgeyaà sura-mardana-priyatamaà sarvärtha-saàvid-varaà sat-sabhyän api tat-kathä-rasa-jhuço bhüyo nanaskurmahe Let us glorify Çréla Vyäsadeva, the spiritual master of the great sages, the literary incarnation of Lord Näräyaëa and the son of Satyavaté. Let us surrender to Vaiçampäyana Muni, the speaker of the Mahäbhärata who became jubilant by drinking the nectar of Lord Viñëu's thousand names. Let us bow down before Kåñëa's friend Bhéñma, the best of the wise and the son of Gaìgä-devé, and let us also bown down before the saintly devotees who relish the narrations of Lord Viñëu's glories. Text 3 nityaà nivasatu hådaye caitanyätmä murärir naù niravadyo nirvåtimaë gajapatir anukampayä yasya May Lord Muräri, who has personally appeared as Çré Caitanya Mahäprabhu, eternally reside within our hearts. He has mercifully purified, engladdened and liberated His devotees, such as Gajendra and Mahäräja Pratäparudra. -

@ 1975: GBC RESOLUTIONS, March 1975

@ 1975: GBC RESOLUTIONS, March 1975 http://www.dandavats.com/wp-content/uploads/GBCresol... @ 1975: GBC RESOLUTIONS, March 1975 1) Jayatirtha presented a definition of GBC, which was accepted as follows: Resolved: The GBC (Governing Body Commissioned) has been established by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada to represent Him in carrying out the responsibility of managing the International Society for Krishna Consciousness of which He is the Founder-Acarya and supreme authority. The GBC accepts as its life and soul His divine instructions and recognizes that it is completely dependent on His mercy in all respects. The GBC has no other function or purpose other than to execute the instructions so kindly given by His Divine Grace and preserve and spread his Teachings to the world in their pure form. It is understood that the GBC, as a collective body of 14-members has been authorized by His Divine Grace to make necessary arrangements for carrying out these responsibilities of management. These arrangements may include delegating authority, managing resources, setting objectives, making plans, calling for reports, evaluating results, training others, maintaining spiritual standards and defining sphere of influence of the various GBC members as well as other devotees. The members of the GBC do not have any inherent authority but rather derive their authority from the Governing Body Commission itself and ultimately from His Divine Grace. Their authority may be over a particular geographic area or over a particular function. Whichever area of responsibility be given to the various members their primary responsibility is to the society as a whole.