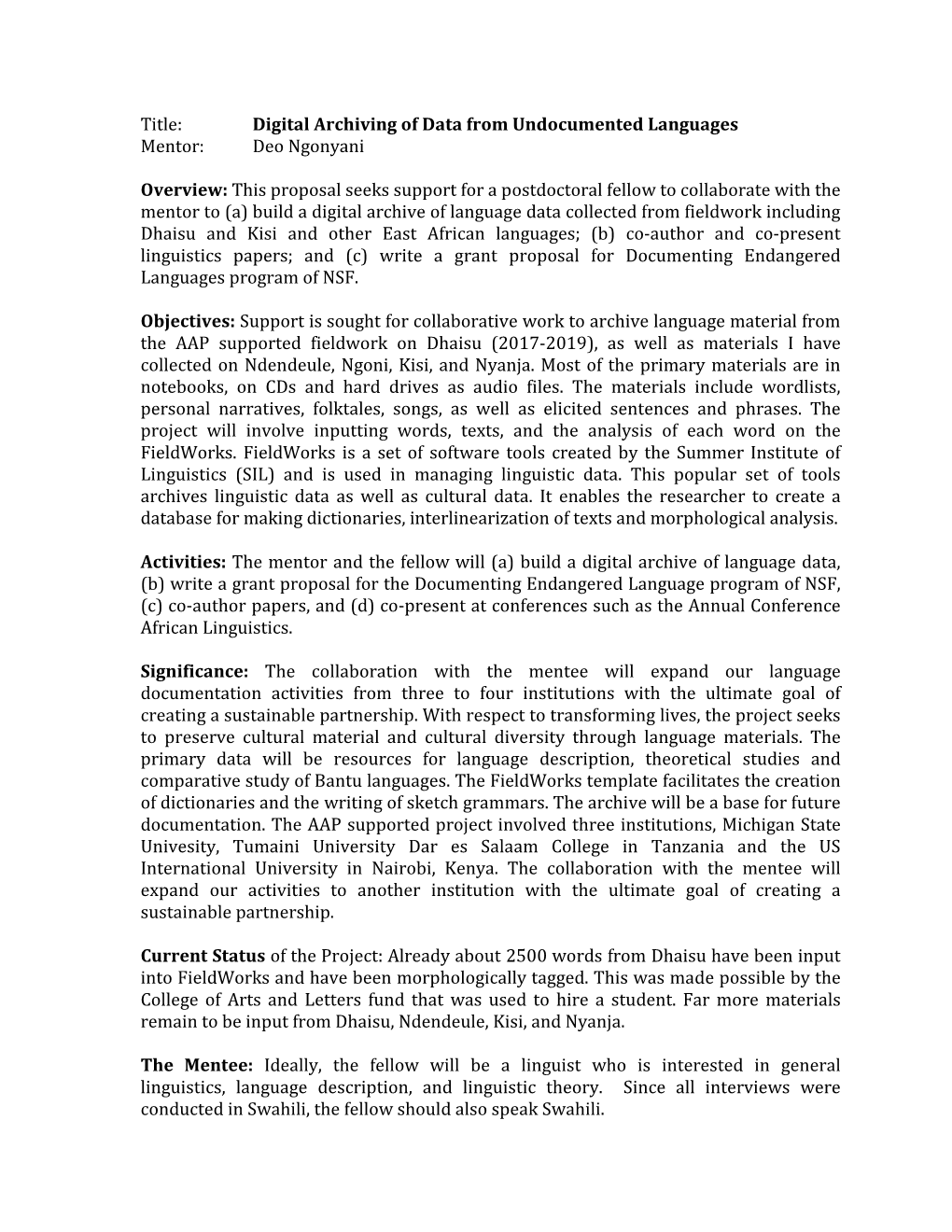

Title: Digital Archiving of Data from Undocumented Languages Mentor: Deo Ngonyani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Closed Adjective Classes and Primary Adjectives in African Languages Guillaume Segerer

Closed adjective classes and primary adjectives in African Languages Guillaume Segerer To cite this version: Guillaume Segerer. Closed adjective classes and primary adjectives in African Languages. 2008. halshs-00255943 HAL Id: halshs-00255943 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00255943 Preprint submitted on 14 Feb 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Closed adjective classes and primary adjectives in African Languages Guillaume Segerer – LLACAN (INALCO, CNRS) Closed adjective classes and primary adjectives in African Languages INTRODUCTION The existence of closed adjective classes (henceforth CAC) has long been recognized for African languages. Although I probably haven’t found the earliest mention of this property1, Welmers’ statement in African Language Structures is often quoted: “It is important to note, however, that in almost all Niger-Congo languages which have a class of adjectives, the class is rather small (...).” (Welmers 1973:250). Maurice Houis provides further precision: “Il y a lieu de noter que de nombreuses langues possèdent des lexèmes adjectivaux. Leur usage en discours est courant, toutefois l’inventaire est toujours limité (autour de 30 à 40 unités).” (Houis 1977:35). These two statements are not further developped by their respective authors. -

Music of Ghana and Tanzania

MUSIC OF GHANA AND TANZANIA: A BRIEF COMPARISON AND DESCRIPTION OF VARIOUS AFRICAN MUSIC SCHOOLS Heather Bergseth A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERDecember OF 2011MUSIC Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2011 Heather Bergseth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor This thesis is based on my engagement and observations of various music schools in Ghana, West Africa, and Tanzania, East Africa. I spent the last three summers learning traditional dance- drumming in Ghana, West Africa. I focus primarily on two schools that I have significant recent experience with: the Dagbe Arts Centre in Kopeyia and the Dagara Music and Arts Center in Medie. While at Dagbe, I studied the music and dance of the Anlo-Ewe ethnic group, a people who live primarily in the Volta region of South-eastern Ghana, but who also inhabit neighboring countries as far as Togo and Benin. I took classes and lessons with the staff as well as with the director of Dagbe, Emmanuel Agbeli, a teacher and performer of Ewe dance-drumming. His father, Godwin Agbeli, founded the Dagbe Arts Centre in order to teach others, including foreigners, the musical styles, dances, and diverse artistic cultures of the Ewe people. The Dagara Music and Arts Center was founded by Bernard Woma, a master drummer and gyil (xylophone) player. The DMC or Dagara Music Center is situated in the town of Medie just outside of Accra. Mr. Woma hosts primarily international students at his compound, focusing on various musical styles, including his own culture, the Dagara, in addition music and dance of the Dagbamba, Ewe, and Ga ethnic groups. -

1 Parameters of Morpho-Syntactic Variation

This paper appeared in: Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 105:3 (2007) 253–338. Please always use the published version for citation. PARAMETERS OF MORPHO-SYNTACTIC VARIATION IN BANTU* a b c By LUTZ MARTEN , NANCY C. KULA AND NHLANHLA THWALA a School of Oriental and African Studies, b University of Leiden and School of Oriental and African Studies, c University of the Witwatersrand and School of Oriental and African Studies ABSTRACT Bantu languages are fairly uniform in terms of broad typological parameters. However, they have been noted to display a high degree or more fine-grained morpho-syntactic micro-variation. In this paper we develop a systematic approach to the study of morpho-syntactic variation in Bantu by developing 19 parameters which serve as the basis for cross-linguistic comparison and which we use for comparing ten south-eastern Bantu languages. We address conceptual issues involved in studying morpho-syntax along parametric lines and show how the data we have can be used for the quantitative study of language comparison. Although the work reported is a case study in need of expansion, we will show that it nevertheless produces relevant results. 1. INTRODUCTION Early studies of morphological and syntactic linguistic variation were mostly aimed at providing broad parameters according to which the languages of the world differ. The classification of languages into ‘inflectional’, ‘agglutinating’, and ‘isolating’ morphological types, originating from the work of Humboldt (1836), is a well-known example of this approach. Subsequent studies in linguistic typology, e.g. work following Greenberg (1963), similarly tried to formulate variables which could be applied to any language and which would classify languages into a number of different types. -

Vidunda (G38) As an Endangered Language?

Vidunda (G38) as an Endangered Language? Karsten Legère University of Gothenburg 1. The position of Swahili and other Tanzanian languages Tanzania is a multi-ethnic and, as a consequence, multi-lingual country. This fact is reflected in the existence of approximately 120 ethnonyms according to the 1967 population census (Tanzania 1971). The most recent edition of Ethnologue (Gordon 2005) lists 128 languages (of which one is extinct) and glossonyms accordingly. This number recently grew even bigger when the results of a country-wide survey under the auspices of LoT1 were released (LoT 2006). Thus, the survey added approximately 80 more glossonyms to the existing lists published by, for example, Polomé & Hill (1980) and Ethnologue. As known, many glossonyms refer to language varieties which are mutually intelligible with those spoken mainly by neighboring ethnic groups or nationalities. People who claim to speak a language of their own frequently understand that of their neighbors, although the latter’s variety is terminologically distinct from the former.2 Hence, the high number of glossonyms is linguistically not relevant for adequately describing the factual situation, which is often characterized by a dialect continuum. In other words, dialect clusters which are comprised of “languages” (as expressed by particular glossonyms) may definitely reduce the number of Tanzanian languages. However, to which number a necessary linguistic and terminological recategorization may ultimately lead is still an open question. The informal and formal spread of Swahili (henceforth called L2) as a language of wider distribution/lingua franca (the national and co-official3 language; see Legère 2006b for discussion) has increasingly limited the use of all other Tanzanian languages (henceforth referred to as L1s). -

Élémentsde Description Du Langi Langue Bantu F.33 De Tanzanie

ÉLÉMENTS DE DESCRIPTION DU LANGI LANGUE BANTU F.33 DE TANZANIE MARGARET DUNHAM Remerciements Je remercie très chaleureusement tous les Valangi, ce sont eux qui ont fourni la matière sur laquelle se fonde cet ouvrage, et notamment : Saidi Ikaji, Maryfrider Joseph, Mama Luci, Yuda, Pascali et Agnès Daudi, Gaitani et Philomena Paoli, M. Sabasi, et toute la famille Ningah : Ally, Saidi, Amina, Jamila, Nasri, Saada et Mei. Je remercie également mes autres amis de Kondoa : Elly Benson, à qui je dois la liste des noms d’arbres qui se trouve en annexe, et Elise Pinners, qui m’a logée à Kondoa et ailleurs. Je remercie le SNV et le HADO à Kondoa pour avoir mis à ma disposition leurs moyens de transport et leur bibliothèque. Je remercie les membres du LACITO du CNRS, tout le groupe Langue-Culture- Environnement et ceux qui ont dirigé le laboratoire pendant ma thèse : Jean-Claude Rivierre, Martine Mazaudon et Zlatka Guentchéva Je remercie tout le groupe bantu : Gladys Guarisma, Raphaël Kaboré, Jacqueline Leroy, Christiane Paulian, Gérard Philippson, Marie-Françoise Rombi et Serge Sauvageot, pour leurs conseils et pour leurs oreilles. Je remercie Jacqueline Vaissière pour ses conseils et sa disponibilité. Je remercie Sophie Manus pour la traduction du swahili du rapport de l’Officier culturel de Kondoa. Je remercie Ewen Macmillan pour son hospitalité chaleureuse et répétée à Londres. Je remercie mes amis à Paris qui ont tant fait pour me rendre la vie agréable pendant ce travail. Je remercie Eric Agnesina pour son aide précieuse, matérielle et morale. Et enfin, je ne saurais jamais assez remercier Marie-Françoise Rombi, pour son amitié et pour son infinie patience. -

An Analysis of the Verbal Marker Tsa in Luguru

AN ANALYSIS OF THE VERBAL MARKER TSA IN LUGURU Malin Petzell University of Gothenburg This paper deals with a morphosyntactic phenomenon found in the under-described Bantu language Luguru, spoken in central Tanzania: the verbal marker tsa. This marker encodes shared knowledge or shared reference. The meanings conveyed by the marker stretch from ‘at a specific time’ or ‘at that place’ to ‘as we know’, or even ‘for that reason’. In Mkude’s grammatical description of Luguru from 1974, there is a mention of a marker (zaa) signalling what he calls “recollected refer- ence”, which restricts the event to one specific moment in the past; this marker is believed to have developed into today’s tsa. 1. INTRODUCTION This paper explores the verbal marker tsa in the under-described Bantu language Luguru, classified as G35 in Guthrie’s (1967–1971) standard classification (ISO 639-3: ruf).1 Luguru is spoken by 403,602 people in the Morogoro region of central Tanzania (Languages of Tanzania Project 2009) and is the major mother tongue in the region. Swahili is the official language and almost all Luguru speakers are bilingual (Petzell & Khül 2017: 36). Below is a map of the languages of the Morogoro region (Figure 1), in which Luguru is marked with green hexagons. The verbal marker tsa, it will be argued, encodes shared knowledge or shared reference. The meanings conveyed by the marker range from ‘at a specific time’ or ‘at that place’ to ‘as we know’, or even ‘for that reason’. Typically, it is used to express determinate moments in the past. -

The Languages of Tanzania There Are About 112 Indi,Enous African Languages in Tanzania (Grimes 1992)

LANGUAGE SHIFI' AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN TANZANIA I Deo Ngonyani Introduction Tanzania is a country of many languages. While Swahili is used by everyone in different situations, vernacular languages are restricted to the different ethnic groups and English is mainly used in education. Vernacular languages, Swahili and English are competitors whose fonuncs are tied to the socio-political changes in the country. In the past flfty years the use of the Swahili language has increased tremendously in Tanzania. Vinually all Tanzanians speak Swahili today and Swahili has become an identity marker for Tanzanians. The use of Swahili has expanded so much that it is now replacing vernacular languages as the language of everyday interaction and is also replacing English as the languaJe of education and government. In this paper, I illusttate that there 1s a process of language shift in Tanzan1a. I also show that due to different factors, Swahili bas become the language of Tanzanian identity. The Language Situtation In order to understand the dynamics propelling Swahili to such a position of prominence, one needs to look at the language situation. In this section I briefly discuss what languages are spoken and for what functions as well as how the different languages relate to each other. The Languages of Tanzania There are about 112 indi,enous African languages in Tanzania (Grimes 1992). The majority o them (101 languages) belong to the Bantu language group. The other African language super-families are also represented. There are 4 Nilotic languages which include Maasai and Tatoga, 5 Cushitic languages such as Iraqw, and 2 Khoisan languages, Hatsa and Sandawe. -

The Classification of the Bantu Languages of Tanzania

i lIMFORIVIATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document h^i(^|eeh used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the qriginal submitted. ■ The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. I.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Mining Page(s)". IfJt was'possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are^spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you'complete continuity. 2. When an.image.on the film is obliterated with li large round black mark, it . is an if}dication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during, exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing' or chart, etc., was part of the material being V- photographed the photographer ' followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to .continue photoing fronTleft to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued, again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until . complete. " - 4. The majority of usefs indicate that the textual content is, of greatest value, ■however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from .'"photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Participation and Language Use

Stichproben. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien Nr. 21/2011, 11. Jg., 63‐117. Participation and language use Irmi Maral‐Hanak First published as chapter 4 in: Maral‐Hanak, Irmi. 2009. Language, discourse and participation: Studies in donor‐ driven development in Tanzania. Wien / Münster: Lit‐Verlag, 115‐156. Multilingualism, colonialism, racism ʺThe term ʹexpatriateʹ itself is an interesting one, on the one hand distinguishing a certain group of people clearly from ʹimmigrantsʹ and other dark‐skinned arrivals, and on the other locating their identity not as ʹforeignersʹ or ʹoutsidersʹ in a host community […] but rather as people whose identity is defined a decontextualized English/American etc. person overseas. Being an ʹexpatriateʹ locates one not as an outsider in a particular community but a permanent insider who happens for the moment to be elsewhere. The very use of this term puts into play a host of significant discoursesʺ (Pennycook 1994:219, endnote to chapter one). Sociolinguistic enquiry focuses on variants in speech and the association of these variants with social factors. A sociolinguistic approach is promising where insights on the implications of language use in society are at stake, such as why ‘development experts’ or ‘beneficiaries’ choose to communicate in one language or variety rather than another, and how the use of a particular language is related to social discrimination and exclusion. From the linguistic vantage point, the object of investigation is the plurality of languages and variations, while from the perspective of social categories it is age, sex and social class (constituted by factors such as education, profession, housing, and others). -

Additive and Substitutive Borrowing Against Semantic Broadening and Narrowing in the Names of Architectural Structures in Tanzanian Bantu Languages

Additive and Substitutive Borrowing against Semantic Broadening and Narrowing in the Names of Architectural Structures in Tanzanian Bantu Languages Amani Lusekelo http://dx.doi./org/10.4314/ujah.v18i1.2 Abstract The thrust of this paper lies on semantic changes associated with additive and substitutive borrowing in Bantu-speaking communities in Tanzania. Due to contact of languages, semantic differences of the terms related to architectural structures emanate. Apart from data from a few elderly native speakers, research was carried out with the help of undergraduate students of linguistics. Further linguistic materials analysed herein come from dictionaries and lexicons. Although retention of the proto- Bantu words are apparent, findings indicate that cases of additive borrowing are obvious for new concepts associated with new architectural structures. The additive Swahili names incorporated into Tanzanian Bantu tend to designate specific concepts associated with modern (contemporary) architectural senses such as mulango ‘modern door’ vs. luigi ‘traditional entranceway’. Cases of substitutive borrowing are rare, as demonstrated by the Swahili word dirisha ‘window’ which replaces chitonono in Chimakonde, echihúru in Runyambo, ilituulo in Kinyakyusa etc. Keywords: Architectural Terms, Additive Borrowing, Onomastics, Semantic Changes, Substitutive Borrowing, Tanzanian Bantu 19 Lusekelo: Additive and Substitutive Borrowing Introduction Linguistic issues emanating from contact languages include additive and substitutive borrowing and semantic narrowing and broadening of both loanwords and native words. For Bantu communities, however, cases of substitutive borrowing are rare and in most instances involve semantic narrowing and broadening (Mapunda & Rosendal 2015). Most of the additive loanwords in Bantu languages of Tanzania come from Kiswahili (Sebonde 2014; Lusekelo 2013; Yoneda 2010) and surround semantic fields associated with ‘agriculture and vegetation’, ‘modern world’, ‘modern healthcare’, ‘formal education’ (Ibid). -

1. Introduction

Kami Malin Petzell & Lotta Aunio 1. Introduction Kami is an endangered, under-described Eastern Bantu language, classified as G36 in Guthrie’s (1967/71) standard classification. It is reported to be spoken by 5,518 people in the Morogoro region of Tanzania (Languages of Tanzania Project, 2009). This figure indicates the total number of persons who consider themselves to speak Kami, but it does not say anything about the competence of those speakers. The number of fluent speakers left is significantly lower, as was established during field trips to the area (2008, 2009, 2014, and 2016). We found no children or adolescents speaking the language, which means that the language is threatened with extinction. Our youngest informant was in his thirties, and he could only understand Kami, not speak it. Swahili, the national language of Tanzania, is gaining ground at the expense of Kami, and is the only language (apart from English) allowed in education, media, parliament, and church. That said, Swahili is not the major threat to Kami – the regional language Luguru is. Luguru is the major language in the Morogoro region, with 403,602 speakers (Languages of Tanzania Project 2009). In the smaller Morogoro district, where most Kami speakers live, the Luguru speakers amount to 73.5% while the Kami speakers amount to only 1.3%, and in the entire Morogoro region, the Kami speakers constitute only 0.3% (Petzell 2012b: 19). This means that most Kami speakers are in fact trilingual in Kami, Luguru, and Swahili. Kami is linguistically similar to its neighbours Kutu (G37), Kwere (G32) and Zalamo (G33) (Petzell & Hammarström 2013). -

Report .R.E S U M E S

REPORT .R.E S U M E S ED 011 120 AL 000 219 SELECTED TITLES IN SOCIOLINGUISTICS,AN INTERIM BIBLIOGRAPHY . OF WORKS ON MULTILINGUALISM,LANGUAGE STANDARDIZATION, AND LANGUAGES OF WIDER COMMUNICATION. BY- PIETRZYK, ALFRED AND OTHERS CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS,WASHINGTON, D.C. PUB DATE MAY 67 EDRS PRICEMF-$9.36 HC-$9.04 226P. DESCRIPTORS- *SOCIOLINGUISTICS,*BIBLIOGRAPHIES, LANGUAGE STANDARDIZATION,MULTILINGUALISM, PIDGINS, SOCIOLINGUISTICS, ETHNICGROUPS, SOCIOLOGY, 'LINGUISTICS',.DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA THIS BIBLIOGRAPHY INCLUDES APRELIMINARY BIBLIOGRAPHY WHICH WAS COMPILED FOR ASOCIOLINGUISTICS-SEMINAR HELD AT THE LINGUISTIC INSTITUTE, BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA,IN THE SUMMER OF 1964 AND AN ADDENDUM ADDED IN MAY1967. THE PRIMARY EMPHASIS IS ON LANGUAGE IN ITS RELATION TOSOCIAL PHENOMENA. THE MAIN AREAS COVERED' ARE' LANGUAGE AND SOCIETY, (2) MULILINGUALISM, (3) LANGUAGE STANDARDIZATION,AND (4) LANGUAGE OFIDER COMMUNICATION. ALISTING OF BIBLIOGRAPHIES RELEVANT TO THE FIELD AND GENERAL REFERENCEWORKS ARE ALSO INCLUDED. ABSTRACTS ARE PROVIDEDFOR MOST OF THE ENTRIES. (RS) CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, 1717 MASSACHUSETTS AVE., N.W.,WASHINGTON, D.0. O r4 ir4I U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION& WELFARE O OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS MEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGAMEATION 0116INA1IN6IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENTOFFICIAL OffICElli EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. SELECTED TITLES IN SOCIOLINGUISTICS An Interim Bibliography of Workson Multilingual ism, Language Standardization, and