Psychologists' Attitudes Towards Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIH Chapter 2: Human Behavior

Aviation Instructor's Handbook (FAA-H-8083-9) Chapter 2: Human Behavior Introduction Derek’s learner, Jason, is very smart and able to retain a lot of information, but has a tendency to rush through the less exciting material and shows interest and attentiveness only when performing tasks that he finds to be interesting. This concerns Derek because he is worried that Jason will overlook many important details and rush through procedures. For a homework assignment Jason was told to take a very thorough look at Preflight Procedures and that for his next flight lesson they would discuss each step in detail. As Derek predicted, Jason found this assignment to be boring and was not prepared. Derek knows that Jason is a “thrill seeker” as he talks about his business, which is a wilderness adventure company. Derek wants to find a way to keep Jason focused and help him find excitement in all areas of learning so that he will understand the complex art of flying and aircraft safety. Learning is the acquisition of knowledge or understanding of a subject or skill through education, experience, practice, or study. This chapter discusses behavior and how it affects the learning process. An instructor seeks to understand why people act the way they do and how people learn. An effective instructor uses knowledge of human behavior, basic human needs, the defense mechanisms humans use that prevent learning, and how adults learn in order to organize and conduct productive learning activities. Definitions of Human Behavior The study of human behavior is an attempt to explain how and why humans function the way they do. -

Chapter 1: the Science of Psychology Module 1: Psychology’S Domains Early Leaders and Approaches in the Study of Psychology

Chapter 1: The Science of Psychology Module 1: Psychology’s Domains Early Leaders and Approaches in the Study of Psychology "Speaking of fruitcakes, any plans for the holidays?" Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920) “the father of psychology” Structuralism “What are the pieces that make up thinking and experience?” To apply scientific principles for study of human mind and behavior, establishes first laboratory in Germany,1879. Proposed School of Structuralism: approach of psychology that mind consists of three basic elements – sensations, feelings, and images. Believed brain was made of up of nonphysical elements – thoughts, emotions, experiences, feelings, etc. Subjects required to look inward (introspection) to describe their emotions or feelings. William James (1842-1910) Harvard professor; pioneer of American psychology. Functionalism Consciousness – awareness - is a stream of ever- changing thoughts; impossible to break it down into individual elements. Most interested how humans function (School of Functionalism Psychology) and adapt to and organize their environment. Thinking developed because it is adaptive. Adaptive behaviors become habits: the “To the infant the world is “flywheel of society.” just a big, booming, buzzing confusion.” Like physical traits, useful behavioral traits could be passed to future generations. Gestalt Germany, 1930s School of Gestalt Psychology: emphasizing how we organize information wholes and integrate separate stimuli into meaningful patterns. Focus on perception – the organization and interpretation of stimuli received and within its context on how it influences behavior and problem solving. “Perceptions are more than the sum of their parts.” Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) Psychoanalysis Austrian, develops first complex personality theory. School of Psychoanalysis Psychology: importance of unconscious motives and conflicts as determinants of human behavior. -

Cognitive Psychology

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY PSYCH 126 Acknowledgements College of the Canyons would like to extend appreciation to the following people and organizations for allowing this textbook to be created: California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Chancellor Diane Van Hook Santa Clarita Community College District College of the Canyons Distance Learning Office In providing content for this textbook, the following professionals were invaluable: Mehgan Andrade, who was the major contributor and compiler of this work and Neil Walker, without whose help the book could not have been completed. Special Thank You to Trudi Radtke for editing, formatting, readability, and aesthetics. The contents of this textbook were developed under the Title V grant from the Department of Education (Award #P031S140092). However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Unless otherwise noted, the content in this textbook is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Table of Contents Psychology .................................................................................................................................................... 1 126 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1 - History of Cognitive Psychology ............................................................................................. 7 Definition of Cognitive Psychology -

INSIDE (2) an Unwarranted Presumption, Which Results in Some Very Serious The- 11 New Membership Dr

P SYCHOLOGYOF R ELIGION A N M IO E T R A I CI CA O N SS PS A YCHOLOGICAL MERICAN SYCHOLOGICAL SSOCIATION OLUME O DI 6 A P A V 32 N 1 VISION 3 EWSLETTER N WINTER 2006–2007 2006 GORMAN AWARD RELIGIONS INFLUENCE WORLDVIEWS; WORLDVIEWS ADDRESS INFLUENCE BEHAVIOR: A MODEL WITH RESEARCH AGENDA MARKE.KOLTKO-RIVERA Professional Services Group, Inc., Winter Park, Florida n emerging trend in public discourse is a renewal of interest in psychological explana- Ations of the phenomenon of religion. I shall point out some problems with that trend, one of which is that it diverts attention from a more interesting issue: religious explana- tions of psychology (i.e., how religion influences individual and social psychological phe- nomena). I shall focus upon this more interesting issue, and how it might be addressed through the use of the construct of Weltanschauung, or worldview. It has been asserted that “within the psychology of religion, the cry for good theory remains at the level of cacophony” (Spilka, Hood, Hunsberger, & Gorsuch, 2003, p. 539). My ambition here is to answer that cry in a useful way. I shall conclude with some suggestions for research. The Revival of Psychological Explanations of Religion Mark E. Koltko-Rivera In recent years, one may have noticed a resurgence of interest in a venerable question: on a fundamental level, how might we explain religion and religious phenomena? In other words, why does religion exist? Two relatively new ways of addressing this question have come into prominence. One involves neuropsychology, and looks at the neurobiological manifestations of religion, belief, and transcendent experience (e.g., Faber, 2004; Har- rington & Zajonc, 2006; McNamara, 2006; Tremlin, 2006; see also Monastersky, 2006). -

The Psychology of Music Haverford College Psychology 303

The Psychology of Music Haverford College Psychology 303 Instructor: Marilyn Boltz Office: Sharpless 407 Contact Info: 610-896-1235 or [email protected] Office Hours: before class and by appointment Course Description Music is a human universal that has been found throughout history and across different cultures of the world. Why, then, is music so ubiquitous and what functions does it serve? The intent of this course is to examine this question from multiple psychological perspectives. Within a biological framework, it is useful to consider the evolutionary origins of music, its neural substrates, and the development of music processing. The field of cognitive psychology raises questions concerning the relationship between music and language, and music’s ability to communicate emotive meaning that may influence visual processing and body movement. From the perspectives of social and personality psychology, music can be argued to serve a number of social functions that, on a more individual level, contribute to a sense of self and identity. Lastly, musical behavior will be considered in a number of applied contexts that include consumer behavior, music therapy, and the medical environment. Prerequisites: Psychology 100, 200, and at least one advanced 200-level course. Biological Perspectives A. Evolutionary Origins of Music When did music evolve in the overall evolutionary scheme of events and why? Does music serve any adaptive purposes or is it, as some have argued, merely “auditory cheesecake”? What types of evidence allows us to make inferences about the origins of music? Reading: Thompson, W.F. (2009). Origins of Music. In W.F. Thompson, Music, thought, and feeling: Understanding the psychology of music. -

Social Psychology Glossary

Social Psychology Glossary This glossary defines many of the key terms used in class lectures and assigned readings. A Altruism—A motive to increase another's welfare without conscious regard for one's own self-interest. Availability Heuristic—A cognitive rule, or mental shortcut, in which we judge how likely something is by how easy it is to think of cases. Attractiveness—Having qualities that appeal to an audience. An appealing communicator (often someone similar to the audience) is most persuasive on matters of subjective preference. Attribution Theory—A theory about how people explain the causes of behavior—for example, by attributing it either to "internal" dispositions (e.g., enduring traits, motives, values, and attitudes) or to "external" situations. Automatic Processing—"Implicit" thinking that tends to be effortless, habitual, and done without awareness. B Behavioral Confirmation—A type of self-fulfilling prophecy in which people's social expectations lead them to behave in ways that cause others to confirm their expectations. Belief Perseverance—Persistence of a belief even when the original basis for it has been discredited. Bystander Effect—The tendency for people to be less likely to help someone in need when other people are present than when they are the only person there. Also known as bystander inhibition. C Catharsis—Emotional release. The catharsis theory of aggression is that people's aggressive drive is reduced when they "release" aggressive energy, either by acting aggressively or by fantasizing about aggression. Central Route to Persuasion—Occurs when people are convinced on the basis of facts, statistics, logic, and other types of evidence that support a particular position. -

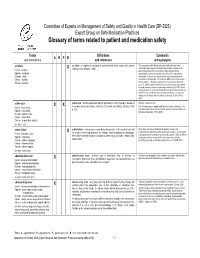

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

Genetics and Human Behaviour

Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 1 Genetics and human behaviour : Genetic screening: ethical issues Published December 1993 the ethical context Human tissue: ethical and legal issues Published April 1995 Animal-to-human transplants: the ethics of xenotransplantation Published March 1996 Mental disorders and genetics: the ethical context Published September 1998 Genetically modified crops: the ethical and social issues Published May 1999 The ethics of clinical research in developing countries: a discussion paper Published October 1999 Stem cell therapy: the ethical issues – a discussion paper Published April 2000 The ethics of research related to healthcare in developing countries Published April 2002 Council on Bioethics Nuffield The ethics of patenting DNA: a discussion paper Published July 2002 Genetics and human behaviour the ethical context Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Internet: www.nuffieldbioethics.org Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 2 Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org ISBN 1 904384 03 X October 2002 Price £3.00 inc p + p (both national and international) Please send cheque in sterling with order payable to Nuffield Foundation © Nuffield Council on Bioethics 2002 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of the publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without prior permission of the copyright owners. -

Music Education and Music Psychology: What‟S the Connection? Research Studies in Music Education

Music Psychology and Music Education: What’s the connection? By: Donald A. Hodges Hodges, D. (2003) Music education and music psychology: What‟s the connection? Research Studies in Music Education. 21, 31-44. Made available courtesy of SAGE PUBLICATIONS LTD: http://rsm.sagepub.com/ ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Abstract: Music psychology is a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary study of the phenomenon of music. The multidisciplinary nature of the field is found in explorations of the anthropology of music, the sociology of music, the biology of music, the physics of music, the philosophy of music, and the psychology of music. Interdisciplinary aspects are found in such combinatorial studies as psychoacoustics (e.g., music perception), psychobiology (e.g., the effects of music on the immune system), or social psychology (e.g., the role of music in social relationships). The purpose of this article is to explore connections between music psychology and music education. Article: ‘What does music psychology have to do with music education?’ S poken in a harsh, accusatory tone (with several expletives deleted), this was the opening salvo in a job interview I once had. I am happy, many years later, to have the opportunity to respond to that question in a more thoughtful and thorough way than I originally did. Because this special issue of Research Studies in Music Education is directed toward graduate students in music education and their teachers, I will proceed on the assumption that most of the readers of this article are more familiar with music education than music psychology. -

Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence: Moving to the Scientific Mainstream

01-Roehlke-4710.qxd 5/11/2005 7:32 PM Page 1 1 SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE: MOVING TO THE SCIENTIFIC MAINSTREAM EUGENE C. ROEHLKEPARTAIN PETER L. BENSON PAMELA EBSTYNE KING LINDA M. WAGENER round the world, there appears to be a within religious communities—worry that the growing concern with spirituality in the beliefs, narratives, and commitments of the A general public as well as among schol- world’s religious traditions are not adequately ars. Whether one looks at the list of best-selling taking root in young people’s lives (e.g., books, searches the Web, watches contemporary Lindner, 2004). As Wuthnow (1998) puts it, movies or TV shows, or reads general-interest “When the sacred no longer has a single magazines, one quickly finds evidence of this address, people worry that it may disappear trend. And one sees religion and spirituality entirely” (p. 10). Other observers contend that (mixed with nationalism and ethnic tensions) the world’s religious heritage is “tainted by an playing defining roles in most major geopoliti- incriminating record of injustice, tribalism, vio- cal conflicts in a world that is becoming both lence, and the violation of fundamental human smaller and more fragmented. rights” (King, 2001 p. 2). Instead, they say, the While spirituality in general has considerable urgent need is to engage young people in new currency, there is additional focus on the spiri- ways of seeing, knowing, and discovering, since tual development of children and adolescents. “a simple return to or retrieval of past spiritual- The source of this interest varies considerably. -

Genetic and Environmental Influences on Human Behavioral Differences

Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1998. 21:1–24 Copyright c 1998 by Annual Reviews Inc. All rights reserved GENETIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES ON HUMAN BEHAVIORAL DIFFERENCES Matt McGue and Thomas J. Bouchard, Jr Department of Psychology and Institute of Human Genetics, 75 East River Road, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455; e-mail: [email protected] KEY WORDS: heritability, gene-environment interaction and correlation, nonshared environ- ment, psychiatric genetics ABSTRACT Human behavioral genetic research aimed at characterizing the existence and nature of genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in cog- nitive ability, personality and interests, and psychopathology is reviewed. Twin and adoption studies indicate that most behavioral characteristics are heritable. Nonetheless, efforts to identify the genes influencing behavior have produced a limited number of confirmed linkages or associations. Behavioral genetic re- search also documents the importance of environmental factors, but contrary to the expectations of many behavioral scientists, the relevant environmental factors appear to be those that are not shared by reared together relatives. The observation of genotype-environment correlational processes and the hypothesized existence of genotype-environment interaction effects serve to distinguish behavioral traits from the medical and physiological phenotypes studied by human geneticists. Be- havioral genetic research supports the heritability, not the genetic determination, of behavior. INTRODUCTION One of the longest, and at times most contentious, debates in Westernintellectual history concerns the relative influence of genetic and environmental factors on human behavioral differences, the so-called nature-nurture debate (Degler 1991). Remarkably, the past generation of behavioral genetic research has led 1 0147-006X/98/0301-0001$08.00 2 McGUE & BOUCHARD many to conclude that it may now be time to retire this debate in favor of a perspective that more strongly emphasizes the joint influence of genes and the environment. -

Mind/Brain/Behavior Study Guide

Guide to the Focus in Mind, Brain, Behavior For History and Science Concentrators Science and Society Track Honors Eligible 2018-2019 Department of the History of Science Science Center 371 ____________________________________________________________________________________ The Focus in Mind, Brain, Behavior in the Science and Society Track offers opportunities for study that are at once more interdisciplinary and more focused than those available to students doing a conventional plan of study in our Department. • More interdisciplinary because the track requires students to take a graduated set of specially designed or specially designated interdisciplinary courses in common with the students in all the other MBB tracks, and also because the track offers the option of augmenting a core historical disciplinary approach to the mind, brain, and behavioral sciences with one auxiliary social science or humanities discipline, such as medical anthropology, public policy, philosophy of mind, etc. • More focused, because it asks students to bring those interdisciplinary perspectives to bear on a particularly vexed arena of scientific inquiry: the mind, brain and behavioral sciences. These include, of course, the neurosciences and cognitive sciences, but also evolutionary perspectives on behavior and cognition, relevant aspects of genetics, and such areas of medical science as psychiatry and psychopharmacology. This study guide offers some guidelines as you go about composing a study program in MBB. The guide outlines the particular areas of focus you can pursue within MBB and offers suggestions for courses you might take within those areas. This study guide is not meant to replace the other available MBB resources or the course guides of the various Harvard divisions.