Towards a Balanced Social Psychology: Causes, Consequences, and Cures for the Problem-Seeking Approach to Social Behavior and Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIH Chapter 2: Human Behavior

Aviation Instructor's Handbook (FAA-H-8083-9) Chapter 2: Human Behavior Introduction Derek’s learner, Jason, is very smart and able to retain a lot of information, but has a tendency to rush through the less exciting material and shows interest and attentiveness only when performing tasks that he finds to be interesting. This concerns Derek because he is worried that Jason will overlook many important details and rush through procedures. For a homework assignment Jason was told to take a very thorough look at Preflight Procedures and that for his next flight lesson they would discuss each step in detail. As Derek predicted, Jason found this assignment to be boring and was not prepared. Derek knows that Jason is a “thrill seeker” as he talks about his business, which is a wilderness adventure company. Derek wants to find a way to keep Jason focused and help him find excitement in all areas of learning so that he will understand the complex art of flying and aircraft safety. Learning is the acquisition of knowledge or understanding of a subject or skill through education, experience, practice, or study. This chapter discusses behavior and how it affects the learning process. An instructor seeks to understand why people act the way they do and how people learn. An effective instructor uses knowledge of human behavior, basic human needs, the defense mechanisms humans use that prevent learning, and how adults learn in order to organize and conduct productive learning activities. Definitions of Human Behavior The study of human behavior is an attempt to explain how and why humans function the way they do. -

The Situational Character: a Critical Realist Perspective on the Human Animal , 93 93 Geo L

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 11-2004 The ituaS tional Character: A Critical Realist Perspective on the Human Animal Jon Hanson Santa Clara University School of Law David Yosifon Santa Clara University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Part of the Law and Economics Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Legal History Commons Automated Citation Jon Hanson and David Yosifon, The Situational Character: A Critical Realist Perspective on the Human Animal , 93 93 Geo L. J. 1 (2004), Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs/59 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Articles The Situational Character: A Critical Realist Perspective on the Human Animal JON HANSON* & DAVID YOSIFON** Th is Article is dedicated to retiring the now-dominant "rational actor" model of human agency, together with its numerous "dispositionist" cohorts, and replacing them with a new conception of human agency that the authors call the "situational character." Th is is a key installment of a larger project recently introduced in an article titled The Situation: An Introduction to the Situational Character, Critical Realism, Power Economics, and Deep Capture. 1 That introduc tory article adumbrated, often in broad stroke, the central premises and some basic conclusions of a new app roach to legal theory and policy analysis. -

Working Memory, Cognitive Miserliness and Logic As Predictors of Performance on the Cognitive Reflection Test

Working Memory, Cognitive Miserliness and Logic as Predictors of Performance on the Cognitive Reflection Test Edward J. N. Stupple ([email protected]) Centre for Psychological Research, University of Derby Kedleston Road, Derby. DE22 1GB Maggie Gale ([email protected]) Centre for Psychological Research, University of Derby Kedleston Road, Derby. DE22 1GB Christopher R. Richmond ([email protected]) Centre for Psychological Research, University of Derby Kedleston Road, Derby. DE22 1GB Abstract Most participants respond that the answer is 10 cents; however, a slower and more analytic approach to the The Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) was devised to measure problem reveals the correct answer to be 5 cents. the inhibition of heuristic responses to favour analytic ones. The CRT has been a spectacular success, attracting more Toplak, West and Stanovich (2011) demonstrated that the than 100 citations in 2012 alone (Scopus). This may be in CRT was a powerful predictor of heuristics and biases task part due to the ease of administration; with only three items performance - proposing it as a metric of the cognitive miserliness central to dual process theories of thinking. This and no requirement for expensive equipment, the practical thesis was examined using reasoning response-times, advantages are considerable. There have, moreover, been normative responses from two reasoning tasks and working numerous correlates of the CRT demonstrated, from a wide memory capacity (WMC) to predict individual differences in range of tasks in the heuristics and biases literature (Toplak performance on the CRT. These data offered limited support et al., 2011) to risk aversion and SAT scores (Frederick, for the view of miserliness as the primary factor in the CRT. -

The Psychology of Music Haverford College Psychology 303

The Psychology of Music Haverford College Psychology 303 Instructor: Marilyn Boltz Office: Sharpless 407 Contact Info: 610-896-1235 or [email protected] Office Hours: before class and by appointment Course Description Music is a human universal that has been found throughout history and across different cultures of the world. Why, then, is music so ubiquitous and what functions does it serve? The intent of this course is to examine this question from multiple psychological perspectives. Within a biological framework, it is useful to consider the evolutionary origins of music, its neural substrates, and the development of music processing. The field of cognitive psychology raises questions concerning the relationship between music and language, and music’s ability to communicate emotive meaning that may influence visual processing and body movement. From the perspectives of social and personality psychology, music can be argued to serve a number of social functions that, on a more individual level, contribute to a sense of self and identity. Lastly, musical behavior will be considered in a number of applied contexts that include consumer behavior, music therapy, and the medical environment. Prerequisites: Psychology 100, 200, and at least one advanced 200-level course. Biological Perspectives A. Evolutionary Origins of Music When did music evolve in the overall evolutionary scheme of events and why? Does music serve any adaptive purposes or is it, as some have argued, merely “auditory cheesecake”? What types of evidence allows us to make inferences about the origins of music? Reading: Thompson, W.F. (2009). Origins of Music. In W.F. Thompson, Music, thought, and feeling: Understanding the psychology of music. -

PSY 324: Social Psychology of Emotion

Advanced Social Psychology: Emotion PSY 324 Section A Spring 2008 Instructor: Christina M. Brown, M.A., A.B.D. CRN: 66773 E-mail: [email protected] Class Time: Monday, Wednesday, Friday Office Hours: 336 Psych MW 2:00-3:00 or by appt 1:00 - 1:50 pm Office Phone: (513) 529-1755 Location: 127 PSYC Required Readings Niedenthal, P. M., Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2006). Psychology of emotion: Interpersonal, experiential, and cognitive approaches. New York: Taylor & Francis. *The textbook is $35 Amazon.com and can be found on Half.com for as cheap as $26. Journal articles will be assigned regularly throughout the semester. These will be available as downloadable .pdf files on Blackboard. Course Description This course is on the advanced social psychology of emotion. Students will gain an understanding of the function of emotion, structure of emotion, and the interplay between emotion, cognition, behavior, and physiology. We will spend most of our time discussing theories of emotion and empirical evidence supporting and refuting these theories. Research is the foundation of psychology, and so a considerable amount of time will be spent reading, discussing, and analyzing research. There will be regular discussions that will each focus on a single assigned reading (always a journal article, which will be made available on Blackboard), and it is my hope that these discussions are active, thoughtful, and generative (meaning that students leave the discussion with research questions and ideas for future research). Although there will be some days entirely devoted to discussion, I hope that we can weave discussion into lecture-based days as well. -

Social Psychology Glossary

Social Psychology Glossary This glossary defines many of the key terms used in class lectures and assigned readings. A Altruism—A motive to increase another's welfare without conscious regard for one's own self-interest. Availability Heuristic—A cognitive rule, or mental shortcut, in which we judge how likely something is by how easy it is to think of cases. Attractiveness—Having qualities that appeal to an audience. An appealing communicator (often someone similar to the audience) is most persuasive on matters of subjective preference. Attribution Theory—A theory about how people explain the causes of behavior—for example, by attributing it either to "internal" dispositions (e.g., enduring traits, motives, values, and attitudes) or to "external" situations. Automatic Processing—"Implicit" thinking that tends to be effortless, habitual, and done without awareness. B Behavioral Confirmation—A type of self-fulfilling prophecy in which people's social expectations lead them to behave in ways that cause others to confirm their expectations. Belief Perseverance—Persistence of a belief even when the original basis for it has been discredited. Bystander Effect—The tendency for people to be less likely to help someone in need when other people are present than when they are the only person there. Also known as bystander inhibition. C Catharsis—Emotional release. The catharsis theory of aggression is that people's aggressive drive is reduced when they "release" aggressive energy, either by acting aggressively or by fantasizing about aggression. Central Route to Persuasion—Occurs when people are convinced on the basis of facts, statistics, logic, and other types of evidence that support a particular position. -

Redalyc. Social Psychology of Mental Health: the Social Structure and Personality Prespective

Scientific Information System Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Esteban Sánchez Moreno, Ana Barrón López de Roda Social Psychology of Mental Health: The Social Structure and Personality Prespective The Spanish Journal of Psychology, vol. 6, núm. 1, mayo, 2003 Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=17260102 The Spanish Journal of Psychology, ISSN (Printed Version): 1138-7416 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España How to cite Complete issue More information about this article Journal's homepage www.redalyc.org Non-Profit Academic Project, developed under the Open Acces Initiative The Spanish Journal of Psychology Copyright 2003 by The Spanish Journal of Psychology 2003, Vol. 6, No. 1, 3-11 1138-7416 Social Psychology of Mental Health: The Social Structure and Personality Perspective Esteban Sánchez Moreno and Ana Barrón López de Roda Complutense University of Madrid Previous research has revealed a persistent association between social structure and mental health. However, most researchers have focused only on the psychological and psychosocial aspects of that relationship. The present paper indicates the need to include the social and structural bases of distress in our theoretical models. Starting from a general social and psychological model, our research considered the role of several social, environmental, and structural variables (social position, social stressors, and social integration), psychological factors (self-esteem), and psychosocial variables (perceived social support). The theoretical model was tested working with a group of Spanish participants (N = 401) that covered a range of social positions. The results obtained using structural equation modeling support our model, showing the relevant role played by psychosocial, psychological and social, and structural factors. -

Mind Perception Daniel R. Ames Malia F. Mason Columbia

Mind Perception Daniel R. Ames Malia F. Mason Columbia University To appear in The Sage Handbook of Social Cognition, S. Fiske and N. Macrae (Eds.) Please do not cite or circulate without permission Contact: Daniel Ames Columbia Business School 707 Uris Hall 3022 Broadway New York, NY 10027 [email protected] 2 What will they think of next? The contemporary colloquial meaning of this phrase often stems from wonder over some new technological marvel, but we use it here in a wholly literal sense as our starting point. For millions of years, members of our evolving species have gazed at one another and wondered: what are they thinking right now … and what will they think of next? The interest people take in each other’s minds is more than idle curiosity. Two of the defining features of our species are our behavioral flexibility—an enormously wide repertoire of actions with an exquisitely complicated and sometimes non-obvious connection to immediate contexts— and our tendency to live together. As a result, people spend a terrific amount of time in close company with conspecifics doing potentially surprising and bewildering things. Most of us resist giving up on human society and embracing the life of a hermit. Instead, most perceivers proceed quite happily to explain and predict others’ actions by invoking invisible qualities such as beliefs, desires, intentions, and feelings and ascribing them without conclusive proof to others. People cannot read one another’s minds. And yet somehow, many times each day, most people encounter other individuals and “go mental,” as it were, adopting what is sometimes called an intentional stance, treating the individuals around them as if they were guided by unseen and unseeable mental states (Dennett, 1987). -

4. Cognitive Heuristics: an Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Cognitive Heuristics and Biases and Their Impact on Negotiations Verfasserin Martina Györik Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Sozial- und Wirtschaftswissenschaften (Mag. rer. soc. oec.) Wien, im November 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 157 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Internationale Betriebswirtschaft Betreuer: O. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Rudolf Vetschera Dedicated to my parents Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 2. The Nature of Human Decision Behavior .............................................. 3 2.1 The Architecture of Cognition .................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Problem Solving, Choice and Judgment .................................................................................. 4 2.3 An Outlook on Decision Analysis ............................................................................................ 6 3. Models of Rationality................................................................................... 9 3.1 Homo œconomicus ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.2 The Concept of Bounded Rationality ..................................................................................... 11 4. Cognitive -

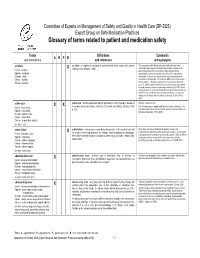

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

David G. Rand

DAVID G. RAND Sloan School (E-62) Room 539 100 Main Street, Cambridge MA 02138 [email protected] EDUCATION 2006-2009 Ph.D., Harvard University, Systems Biology 2000-2004 B.A., Cornell University summa cum laude, Computational Biology PROFESSIONAL Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2019- Erwin H. Schell Professorship 2018- Associate Professor (tenured) of Management Science, Sloan School 2018- Secondary appointment, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences 2018- Affiliated faculty, Institute for Data, Systems, and Society Yale University 2017-2018 Associate Professor (tenured) – Psychology Department 2016-2017 Associate Professor (untenured) – Psychology Department 2013-2016 Assistant Professor – Psychology Department 2013-2018 Appointment by courtesy, Economics Department 2013-2018 Appointment by courtesy, School of Management 2013-2018 Cognitive Science Program 2013-2018 Institution for Social and Policy Studies 2013-2018 Yale Institute for Network Science Applied Cooperation Team (ACT) 2013- Director Harvard University 2012-2013 Postdoctoral Fellow – Psychology Department 2011 Lecturer – Human Evolutionary Biology Department 2010-2012 FQEB Prize Fellow – Psychology Department 2009-2013 Research Scientist – Program for Evolutionary Dynamics 2009-2011 Fellow – Berkman Center for Internet & Society 2006-2009 Ph.D. Student – Systems Biology 2004-2006 Mathematical Modeler – Gene Network Sciences, Ithaca NY 2003-2004 Undergraduate Research Assistant – Psychology, Cornell University 2002-2004 Undergraduate Research Assistant – Plant Biology, Cornell University SELECTED PUBLICATIONS [*Equal contribution] Mosleh M, Arechar AA, Pennycook G, Rand DG (In press) Cognitive reflection correlates with behavior on Twitter. Nature Communications. Bago B, Rand DG, Pennycook G (2020) Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines. Journal of Experimental Psychology:General. doi:10.1037/xge0000729 Dias N, Pennycook G, Rand DG (2020) Emphasizing publishers does not effectively reduce susceptibility to misinformation on social media. -

Genetics and Human Behaviour

Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 1 Genetics and human behaviour : Genetic screening: ethical issues Published December 1993 the ethical context Human tissue: ethical and legal issues Published April 1995 Animal-to-human transplants: the ethics of xenotransplantation Published March 1996 Mental disorders and genetics: the ethical context Published September 1998 Genetically modified crops: the ethical and social issues Published May 1999 The ethics of clinical research in developing countries: a discussion paper Published October 1999 Stem cell therapy: the ethical issues – a discussion paper Published April 2000 The ethics of research related to healthcare in developing countries Published April 2002 Council on Bioethics Nuffield The ethics of patenting DNA: a discussion paper Published July 2002 Genetics and human behaviour the ethical context Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Internet: www.nuffieldbioethics.org Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 2 Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org ISBN 1 904384 03 X October 2002 Price £3.00 inc p + p (both national and international) Please send cheque in sterling with order payable to Nuffield Foundation © Nuffield Council on Bioethics 2002 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of the publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without prior permission of the copyright owners.