Mind/Brain/Behavior Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIH Chapter 2: Human Behavior

Aviation Instructor's Handbook (FAA-H-8083-9) Chapter 2: Human Behavior Introduction Derek’s learner, Jason, is very smart and able to retain a lot of information, but has a tendency to rush through the less exciting material and shows interest and attentiveness only when performing tasks that he finds to be interesting. This concerns Derek because he is worried that Jason will overlook many important details and rush through procedures. For a homework assignment Jason was told to take a very thorough look at Preflight Procedures and that for his next flight lesson they would discuss each step in detail. As Derek predicted, Jason found this assignment to be boring and was not prepared. Derek knows that Jason is a “thrill seeker” as he talks about his business, which is a wilderness adventure company. Derek wants to find a way to keep Jason focused and help him find excitement in all areas of learning so that he will understand the complex art of flying and aircraft safety. Learning is the acquisition of knowledge or understanding of a subject or skill through education, experience, practice, or study. This chapter discusses behavior and how it affects the learning process. An instructor seeks to understand why people act the way they do and how people learn. An effective instructor uses knowledge of human behavior, basic human needs, the defense mechanisms humans use that prevent learning, and how adults learn in order to organize and conduct productive learning activities. Definitions of Human Behavior The study of human behavior is an attempt to explain how and why humans function the way they do. -

The Psychology of Music Haverford College Psychology 303

The Psychology of Music Haverford College Psychology 303 Instructor: Marilyn Boltz Office: Sharpless 407 Contact Info: 610-896-1235 or [email protected] Office Hours: before class and by appointment Course Description Music is a human universal that has been found throughout history and across different cultures of the world. Why, then, is music so ubiquitous and what functions does it serve? The intent of this course is to examine this question from multiple psychological perspectives. Within a biological framework, it is useful to consider the evolutionary origins of music, its neural substrates, and the development of music processing. The field of cognitive psychology raises questions concerning the relationship between music and language, and music’s ability to communicate emotive meaning that may influence visual processing and body movement. From the perspectives of social and personality psychology, music can be argued to serve a number of social functions that, on a more individual level, contribute to a sense of self and identity. Lastly, musical behavior will be considered in a number of applied contexts that include consumer behavior, music therapy, and the medical environment. Prerequisites: Psychology 100, 200, and at least one advanced 200-level course. Biological Perspectives A. Evolutionary Origins of Music When did music evolve in the overall evolutionary scheme of events and why? Does music serve any adaptive purposes or is it, as some have argued, merely “auditory cheesecake”? What types of evidence allows us to make inferences about the origins of music? Reading: Thompson, W.F. (2009). Origins of Music. In W.F. Thompson, Music, thought, and feeling: Understanding the psychology of music. -

Social Psychology Glossary

Social Psychology Glossary This glossary defines many of the key terms used in class lectures and assigned readings. A Altruism—A motive to increase another's welfare without conscious regard for one's own self-interest. Availability Heuristic—A cognitive rule, or mental shortcut, in which we judge how likely something is by how easy it is to think of cases. Attractiveness—Having qualities that appeal to an audience. An appealing communicator (often someone similar to the audience) is most persuasive on matters of subjective preference. Attribution Theory—A theory about how people explain the causes of behavior—for example, by attributing it either to "internal" dispositions (e.g., enduring traits, motives, values, and attitudes) or to "external" situations. Automatic Processing—"Implicit" thinking that tends to be effortless, habitual, and done without awareness. B Behavioral Confirmation—A type of self-fulfilling prophecy in which people's social expectations lead them to behave in ways that cause others to confirm their expectations. Belief Perseverance—Persistence of a belief even when the original basis for it has been discredited. Bystander Effect—The tendency for people to be less likely to help someone in need when other people are present than when they are the only person there. Also known as bystander inhibition. C Catharsis—Emotional release. The catharsis theory of aggression is that people's aggressive drive is reduced when they "release" aggressive energy, either by acting aggressively or by fantasizing about aggression. Central Route to Persuasion—Occurs when people are convinced on the basis of facts, statistics, logic, and other types of evidence that support a particular position. -

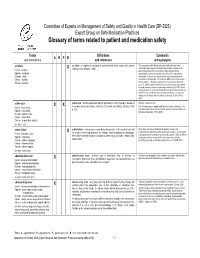

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

Genetics and Human Behaviour

Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 1 Genetics and human behaviour : Genetic screening: ethical issues Published December 1993 the ethical context Human tissue: ethical and legal issues Published April 1995 Animal-to-human transplants: the ethics of xenotransplantation Published March 1996 Mental disorders and genetics: the ethical context Published September 1998 Genetically modified crops: the ethical and social issues Published May 1999 The ethics of clinical research in developing countries: a discussion paper Published October 1999 Stem cell therapy: the ethical issues – a discussion paper Published April 2000 The ethics of research related to healthcare in developing countries Published April 2002 Council on Bioethics Nuffield The ethics of patenting DNA: a discussion paper Published July 2002 Genetics and human behaviour the ethical context Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Internet: www.nuffieldbioethics.org Cover final A/W13657 19/9/02 11:52 am Page 2 Published by Nuffield Council on Bioethics 28 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JS Telephone: 020 7681 9619 Fax: 020 7637 1712 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org ISBN 1 904384 03 X October 2002 Price £3.00 inc p + p (both national and international) Please send cheque in sterling with order payable to Nuffield Foundation © Nuffield Council on Bioethics 2002 All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of the publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without prior permission of the copyright owners. -

Music Education and Music Psychology: What‟S the Connection? Research Studies in Music Education

Music Psychology and Music Education: What’s the connection? By: Donald A. Hodges Hodges, D. (2003) Music education and music psychology: What‟s the connection? Research Studies in Music Education. 21, 31-44. Made available courtesy of SAGE PUBLICATIONS LTD: http://rsm.sagepub.com/ ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Abstract: Music psychology is a multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary study of the phenomenon of music. The multidisciplinary nature of the field is found in explorations of the anthropology of music, the sociology of music, the biology of music, the physics of music, the philosophy of music, and the psychology of music. Interdisciplinary aspects are found in such combinatorial studies as psychoacoustics (e.g., music perception), psychobiology (e.g., the effects of music on the immune system), or social psychology (e.g., the role of music in social relationships). The purpose of this article is to explore connections between music psychology and music education. Article: ‘What does music psychology have to do with music education?’ S poken in a harsh, accusatory tone (with several expletives deleted), this was the opening salvo in a job interview I once had. I am happy, many years later, to have the opportunity to respond to that question in a more thoughtful and thorough way than I originally did. Because this special issue of Research Studies in Music Education is directed toward graduate students in music education and their teachers, I will proceed on the assumption that most of the readers of this article are more familiar with music education than music psychology. -

Genetic and Environmental Influences on Human Behavioral Differences

Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1998. 21:1–24 Copyright c 1998 by Annual Reviews Inc. All rights reserved GENETIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES ON HUMAN BEHAVIORAL DIFFERENCES Matt McGue and Thomas J. Bouchard, Jr Department of Psychology and Institute of Human Genetics, 75 East River Road, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455; e-mail: [email protected] KEY WORDS: heritability, gene-environment interaction and correlation, nonshared environ- ment, psychiatric genetics ABSTRACT Human behavioral genetic research aimed at characterizing the existence and nature of genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in cog- nitive ability, personality and interests, and psychopathology is reviewed. Twin and adoption studies indicate that most behavioral characteristics are heritable. Nonetheless, efforts to identify the genes influencing behavior have produced a limited number of confirmed linkages or associations. Behavioral genetic re- search also documents the importance of environmental factors, but contrary to the expectations of many behavioral scientists, the relevant environmental factors appear to be those that are not shared by reared together relatives. The observation of genotype-environment correlational processes and the hypothesized existence of genotype-environment interaction effects serve to distinguish behavioral traits from the medical and physiological phenotypes studied by human geneticists. Be- havioral genetic research supports the heritability, not the genetic determination, of behavior. INTRODUCTION One of the longest, and at times most contentious, debates in Westernintellectual history concerns the relative influence of genetic and environmental factors on human behavioral differences, the so-called nature-nurture debate (Degler 1991). Remarkably, the past generation of behavioral genetic research has led 1 0147-006X/98/0301-0001$08.00 2 McGUE & BOUCHARD many to conclude that it may now be time to retire this debate in favor of a perspective that more strongly emphasizes the joint influence of genes and the environment. -

THEORETICAL BEHAVIORISM John Staddon Duke University “Isms”

Behavior and Philosophy, 45, 27-44 (2017). © 2017 Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies THEORETICAL BEHAVIORISM John Staddon Duke University Abstract: B. F. Skinner’s radical behaviorism has been highly successful experimentally, revealing new phenomena with new methods. But Skinner’s dismissal of theory limited its development. Theoretical behaviorism recognizes that a historical system, an organism, has a state as well as sensitivity to stimuli and the ability to emit responses. Indeed, Skinner himself acknowledged the possibility of what he called “latent” responses in humans, even though he neglected to extend this idea to rats and pigeons. Latent responses constitute a repertoire, from which operant reinforcement can select. The paper describes some applications of theoretical behaviorism to operant learning. Key words: Skinner, response repertoire, teaching, classical conditioning, memory “Isms” are rarely a “plus” for science. The suffix sounds political. It implies a coherence and consistency that is rarely matched by reality. But labels are effective rhetorically. J. B. Watson’s 1913 behaviorist paper (Watson, 1913) would not have been as influential without his rather in-your-face term. Theoretical behaviorism accepts the “ism” with reluctance. ThB is not a doctrine or even a philosophy. As I will try to show, it is an attempt to bring behavioristic psychology back into the mainstream of science: avoiding the Scylla of atheoretical simplism on one side and the Charybdis of scientistic mentalism on the other. John Watson was both realistic and naïve. The realism was in his rejection of the subjective, of first-person accounts as a part of science. ‘Qualia’ are not data and little has been learned through reports of conscious experience. -

The Psychology of Music

16 Comparative Music Cognition: Cross-Species and Cross-Cultural Studies Aniruddh D. Patelà and Steven M. Demorest† ÃDepartment of Psychology, Tufts University, Medford, Massachusetts; †School of Music, University of Washington, Seattle I. Introduction Music, according to the old saw, is the universal language. Yet a few observations quickly show that this is untrue. Our familiar animal companions, such as dogs and cats, typically show little interest in our music, even though they have been domes- ticated for thousands of years and are often raised in households where music is frequently heard. More formally, a scientific study of nonhuman primates (tamarins and marmosets) showed that when given the choice of listening to human music or silence, the animals chose silence (McDermott & Hauser, 2007). Such observations clearly challenge the view that our sense of music simply reflects the auditory system’s basic response to certain frequency ratios and temporal patterns, combined with basic psychological mechanisms such as the ability to track the probabilities of different events in a sound sequence. Were this the case, we would expect many species to show an affinity for music, since basic pitch, timing, and auditory sequencing abilities are likely to be similar in humans and many other animals (Rauschecker & Scott, 2009). Hence although these types of processing are doubt- lessly relevant to our musicality, they are clearly not the whole story. Our sense of music reflects the operation of a rich and multifaceted cognitive system, with many processing capacities working in concert. Some of these capacities are likely to be uniquely human, whereas others are likely to be shared with nonhuman animals. -

Towards a Balanced Social Psychology: Causes, Consequences, and Cures for the Problem-Seeking Approach to Social Behavior and Cognition

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2004) 27, 000–000 Printed in the United States of America Towards a balanced social psychology: Causes, consequences, and cures for the problem-seeking approach to social behavior and cognition Joachim I. Krueger Department of Psychology, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912. [email protected] http://www.brown.edu/departments/psychology/faculty/krueger.html David C. Funder Department of Psychology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92506 [email protected] http://www.psych.ucr.edu/faculty/funder/rap/rap.htm Abstract: Mainstream social psychology focuses on how people characteristically violate norms of action through social misbehaviors such as conformity with false majority judgments, destructive obedience, and failures to help those in need. Likewise, they are seen to violate norms of reasoning through cognitive errors such as misuse of social information, self-enhancement, and an over-readiness to at- tribute dispositional characteristics. The causes of this negative research emphasis include the apparent informativeness of norm viola- tion, the status of good behavior and judgment as unconfirmable null hypotheses, and the allure of counter-intuitive findings. The short- comings of this orientation include frequently erroneous imputations of error, findings of mutually contradictory errors, incoherent interpretations of error, an inability to explain the sources of behavioral or cognitive achievement, and the inhibition of generalized the- ory. Possible remedies include increased attention to the complete range of behavior and judgmental accomplishment, analytic reforms emphasizing effect sizes and Bayesian inference, and a theoretical paradigm able to account for both the sources of accomplishment and of error. A more balanced social psychology would yield not only a more positive view of human nature, but also an improved under- standing of the bases of good behavior and accurate judgment, coherent explanations of occasional lapses, and theoretically grounded suggestions for improvement. -

Quick Study Guide Topic: Subfields in Psychology Related Course(S): Psych 1100, 2800, 3000, 3200

Office of the Dean of Instructional Services Tutorial Services I Dean of Instructional Services l Instructional Computing Institutional Research I Computing & Information Technology l Testing Quick Study Guide Topic: Subfields in Psychology Related Course(s): Psych 1100, 2800, 3000, 3200 Subfields in Psychology – Concepts & Definitions Behavioral neuroscience – subfield of psychology that mainly examines how the brain and the nervous system, but other biological processes as well, determine behavior. Clinical Psychology – Focuses on diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and problematic patterns of behavior. Study involves clinical therapy and counseling. Cognitive Psychology – Branch of psychology that focuses on cognition (thoughts) Counseling Psychology – similar to Clinical and focuses on emotional, social, vocational, and health-related outcomes in individuals who are considered psychologically healthy. Developmental Psychology – Developmental psychology studies the physical and mental attributes of aging and maturation. This can include how cognitive, social and psychological skills are acquired throughout growth. Evolutionary psychology – considers how behavior is influenced by our genetic inheritance from our ancestors Experimental psychology – is the branch of psychology that studies the processes of sensing, perceiving, learning, and thinking about the world Forensic Psychology – Branch of psychology dealing with justice system. Tasks of Forensic Psychologists include assessment of individuals' mental competency to stand in trial, sentencing and treatment suggestions, and advisement regarding eyewitness testimonies. This field of psychology requires a strong understanding of the legal system. Health Psychology – Branch that focuses on how individual health is directly related or affected by biological, psychological, and sociocultural influences. Industrial/Organizational Psychology – Applies theories, principles and research findings tin industrial (businesses) and organizational settings. -

Social Cognitive Theory

1 SOCIAL COGNITIVE THEORY Albert Bandura Stanford University Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of child development. Vol. 6. Six theories of child development (pp. 1-60). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. 2 Many theories have been proposed over the years to explain the developmental changes that people undergo over the course of their lives. These theories differ in the conceptions of human nature they adopt and in what they regard to be the basic causes and mechanisms of human motivation and behavior. The present chapter analyzes human development from the perspective of social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986). Since development is a life- long process (Baltes & Reese, 1984), the analysis is concerned with changes in the psychosocial functioning of adults as well as with those occurring in childhood. Development is not a monolithic process. Human capabilities vary in their psychobiologic origins and in the experiential conditions needed to enhance and sustain them. Human development, therefore, encompasses many different types and patterns of changes. Diversity in social practices produces substantial individual differences in the capabilities that are cultivated and those that remain underdeveloped. Triadic Reciprocal Determinism Before analyzing the development of different human capabilities, the model of causation on which social cognitive theory is founded is reviewed briefly. Human behavior has often been explained in terms of one-sided determinism. In such modes of unidirectional causation, behavior is depicted as being shaped and controlled either by environmental influences or by internal dispositions. Social cognitive theory favors a model of causation involving triadic reciprocal determinism. In this model of reciprocal causation, behavior, cognition and other personal factors, and environmental influences all operate as interacting determinants that influence each other bidirectionally (Figure 1).