The Press, the Documentaries and the Byrd Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001 “The Sensational Landscape: The History of Sensationalist Images of the Arctic, 1818-1910,” 2001. Supervisor: William Morrison UNBC Library call number: G630.G7 S74 2001 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the public perception of the Arctic through explorers’ journals and the modern press in America and Britain. The underlying question of this thesis is what exactly was the role of the press in forming public opinions about Arctic exploration in general? Did newspaper editors in America and Britain simply report what they found interesting based upon their own knowledge of Arctic explorers’ journals, or did these editors create that public interest in order to profit from increased sales? From a historical perspective, these reasons relate to the growth of an intellectual and social current that had been gaining strength on the Western World throughout the nineteenth century: the creation of the mythic hero. In essence, the mythical status of Arctic explorers developed in Britain, but was matured and honed in the American press, particularly in the competitive news industry in New York where the creation of the heroic Arctic explorer resulted largely from the vicious competitiveness of the contemporary press. Although the content of published Arctic exploration journals in the early nineteenth century did not change dramatically, the accuracy of those journals did. Exploration journals up until 1850 tended to focus heavily on the conventions of the sublime and picturesque to describe these new lands. However, these views were inaccurate, for these conventions forced the explorer to view the Arctic very much as they viewed the Swiss Alps or the English countryside. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

Rather Than Imposing Thematic Unity Or Predefining a Common Theoretical

The Supernatural Arctic: An Exploration Shane McCorristine, University College Dublin Abstract The magnetic attraction of the North exposed a matrix of motivations for discovery service in nineteenth-century culture: dreams of wealth, escape, extreme tourism, geopolitics, scientific advancement, and ideological attainment were all prominent factors in the outfitting expeditions. Yet beneath this „exoteric‟ matrix lay a complex „esoteric‟ matrix of motivations which included the compelling themes of the sublime, the supernatural, and the spiritual. This essay, which pivots around the Franklin expedition of 1845-1848, is intended to be an exploration which suggests an intertextuality across Arctic time and geography that was co-ordinated by the lure of the supernatural. * * * Introduction In his classic account of Scott‟s Antarctic expedition Apsley Cherry- Garrard noted that “Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time which has been devised”.1 If there is one single question that has been asked of generations upon generations of polar explorers it is, Why?: Why go through such ordeals, experience such hardship, and take such risks in order to get from one place on the map to another? From an historical point of view, with an apparent fifty per cent death rate on polar voyages in the long nineteenth century amid disaster after disaster, the weird attraction of the poles in the modern age remains a curious fact.2 It is a less curious fact that the question cui bono? also featured prominently in Western thinking about polar exploration, particularly when American expeditions entered the Arctic 1 Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World. -

Annual Report FY15: July 1, 2014–June 30, 2015

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC Annual Report Fiscal Year 2015 COA Development Office College of the Atlantic 105 Eden Street Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 Dean of Institutional Advancement Lynn Boulger 207-801-5620, [email protected] Development Associate Amanda Ruzicka Mogridge 207-801-5625, [email protected] Development Officer Kristina Swanson 207-801-5621, [email protected] Alumni Relations/Development Coordinator Dianne Clendaniel 207-801-5624, [email protected] Manager of Donor Engagement Jennifer Hughes 207-801-5622, [email protected] Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in preparing all donor lists for this annual report. If a mistake has been made in your name, or if your name was omitted, we apologize. Please notify the development office at 207-801-5625 with any changes. www.coa.edu/support COA ANNUAL REPorT FY15: July 1, 2014–June 30, 2015 I love nothing more than telling stories of success and good news about our We love to highlight the achievements of our students, and one that stands out incredible college. One way I tell these stories is through a series I’ve created for from last year is the incredible academic recognition given to Ellie Oldach '15 our Board of Trustees called the College of the Atlantic Highlight Reel. A perusal of when she received a prestigious Fulbright Research Scholarship. It was the first the Reels from this year include the following elements: time in the history of the college that a student has won a Fulbright. Ellie is spending ten months on New Zealand’s South Island working to understand and COA received the 2014 Honor Award from Maine Preservation for our model coastal marsh and mussel bed communities. -

The North Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: an Historical Perspective

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State History Theses History and Social Studies Education 12-2011 The orN th Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective Kayla J. Shypski [email protected] Advisor Dr. Cynthia A. Conides First Reader Cynthia A. Conides, Ph.D., Associate Professor of History and Social Studies Education, Director of Museum Studies Second Reader Lisa Marie Anselmi, Ph.D., R.P.A., Associate Professor and Chair of the Anthropology Department Department Chair Andrew D. Nicholls To learn more about the History and Social Studies Education Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://history.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Shypski, Kayla J., "The orN th Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective" (2011). History Theses. Paper 2. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons i ABSTRACT OF THESIS The North Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective Polar exploration was a large part of American culture and society during the mid to late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. The North Pole controversy of 1909 in which two American Arctic explorers both claimed to have reached the North Pole was a culmination of the polar exploration era. However, one aspect of the polar expeditions that is relatively unknown is the treatment of the native Inuit peoples of the Arctic by the polar explorers. -

Lingering Apologia for the Byrd North Pole Hoax

Peary&Byrd Fakes Still Obscure Amundsen First Lingering Apologia for the Byrd North Pole Hoax MythCling in the Face of Diary's Unexceedable Counterproof Ohio State University Vs Ohioan Ellsworth's Achievement Fellow Pocahantas Descendants InDenial by Dennis Rawlins www.dioi.org/by.pdf 2019/2/12 [email protected] [See article's end for source-abbreviations.] A First Families A1 In 2013 appeared a 560pp book by Sheldon Bart, stimulatingly entitled Race to the Top of the World: Richard Byrd and the First Flight to the North Pole, with the jacketjuiced aim of rehabbing Adm. Byrd's and copilot Floyd Bennett's tattered claim to have been first by air to the North Pole of the Earth, flying from Spitzbergen's KingsBay allegedly to the Pole and back on 1926/5/9 in the Fokker trimotor airplane the Josephine Ford. The flight occurred 3d prior to the 1926/5/12 arrival at the Pole of the Norge dirigible expedition of Norway's Roald Amundsen, Ohio's Lincoln Ellsworth, and Italy's Umberto Nobile (who designed & copiloted the airship). The Norge reached the Pole on 1926/5/12, Ellsworth's birthday, and arrived a few days later at Pt.Barrow, Alaska. The shortest distance between KingsBay and Pt.Barrow being virtually over the North Pole, there was no doubt of the Norge's success, leaving only the question of whether Byrd's in&out flight had gone far enough to hit the Pole in the short time it was out of sight. A2 Defending Byrd's 1926 tale at this point is a Sisyphan errand, given the varied disproofs1 revealed by DIO — primarily huge discrepancies between the Byrd diary's solar sextant data vs his official reports (RX p.7&xxEF&MN). -

Roald Amundsen Essay Prepared for the Encyclopedia of the Arctic by Jonathan M

Roald Amundsen Essay prepared for The Encyclopedia of the Arctic By Jonathan M. Karpoff No polar explorer can lay claim to as many major accomplishments as Roald Amundsen. Amundsen was the first to navigate a Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the first to reach the South Pole, and the first to lay an undisputed claim to reaching the North Pole. He also sailed the Northeast Passage, reached a farthest north by air, and made the first crossing of the Arctic Ocean. Amundsen also was an astute and respectful ethnographer of the Netsilik Inuits, leaving valuable records and pictures of a two-year stay in northern Canada. Yet he appears to have been plagued with a public relations problem, regarded with suspicion by many as the man who stole the South Pole from Robert F. Scott, constantly having to fight off creditors, and never receiving the same adulation as his fellow Norwegian and sometime mentor, Fridtjof Nansen. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was born July 16, 1872 in Borge, Norway, the youngest of four brothers. He grew up in Oslo and at a young age was fascinated by the outdoors and tales of arctic exploration. He trained himself for a life of exploration by taking extended hiking and ski trips in Norway’s mountains and by learning seamanship and navigation. At age 25, he signed on as first mate for the Belgica expedition, which became the first to winter in the south polar region. Amundsen would form a lifelong respect for the Belgica’s physician, Frederick Cook, for Cook’s resourcefulness in combating scurvy and freeing the ship from the ice. -

Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott: Amundsen’S Earlier Voyages and Experience

Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott: Amundsen’s earlier voyages and experience. • Roald Amundsen joined the Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–99) as first mate. • This expedition, led by Adrien de Gerlache using the ship the RV Belgica, became the first expedition to winter in Antarctica. Voyage in research vessel Belgica. • The Belgica, whether by mistake or design, became locked in the sea ice at 70°30′S off Alexander Island, west of the Antarctic Peninsula. • The crew endured a winter for which they were poorly prepared. • RV Belgica frozen in the ice, 1898. Gaining valuable experience. • By Amundsen's own estimation, the doctor for the expedition, the American Frederick Cook, probably saved the crew from scurvy by hunting for animals and feeding the crew fresh meat • In cases where citrus fruits are lacking, fresh meat from animals that make their own vitamin C (which most do) contains enough of the vitamin to prevent scurvy, and even partly treat it. • This was an important lesson for Amundsen's future expeditions. Frederick Cook с. 1906. Another successful voyage. • In 1903, Amundsen led the first expedition to successfully traverse Canada's Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. • He planned a small expedition of six men in a 45-ton fishing vessel, Gjøa, in order to have flexibility. Gjøa today. Sailing westward. • His ship had relatively shallow draft. This was important since the depth of the sea was about a metre in some places. • His technique was to use a small ship and hug the coast. Amundsen had the ship outfitted with a small gasoline engine. -

The Press, the Documentaries and the Byrd Archives

THE AMERICAN ARCHIVIST Archives in Controversy: The Press, the Documentaries Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/62/2/307/2749198/aarc_62_2_t1u7854068882508.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 and the Byrd Archives Raimund E. Goerler Abstract One of the major news stories of 1996 was the discovery and analysis of Richard Byrd's diary and notebook for his North Pole flight of 1926. Byrd's claim to be die first to fly to the North Pole was challenged by his contemporaries and by later historians. The diary provided new evidence, and the news of its existence and meaning fueled stories that reached every part of the globe. Interest in Byrd also inspired producers of three documentaries. The archivist who dealt widi reporters and producers discusses die media coverage, the challenges of working with reporters and producers of documentaries, and the impact of the publicity on an archival program. n May 9,1996, the seventieth anniversary of Richard Byrd's flight to the North Pole, Ohio State University ("OSU") announced the discovery Oof a diary of the flight. The story about Byrd's diary appeared in news- papers and on television and radio across the United States and Europe, and as far away as Australia. At die end of 1996 columnist George Will ranked the story as one of the year's biggest, especially because of an interpretation of the diary that cast doubt upon Byrd's accomplishment.1 Producers also followed the Byrd story and used archival materials for three separate television documentaries. Rarely have archivists experienced such controversy over an event covered by the media.2 The publicity and the dramatic productions that followed the 1 George F. -

Chapter 8: Surface and Deep Circulation Exploring the World

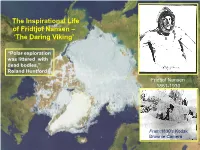

The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 Fram:1890’s Kodak Brownie Camera The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ Events of Period U.S. Civil War 1861-1865 2nd Industrial Rev. 1880‟s Fridtjof Nansen World War I 1861-1930 1914-1918 League of Nations 1919 Rise of Bolshevism 1920‟s Fram:1890’s Kodak Brownie Camera The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930) * Nansen‟s Youth * Education/Sportsman * Early Career Accomplishments * First Research Cruise * Greenland Crossing * Farthest North and Accolades * More Oceanographic Research * Statesman and Diplomat * Humanitarian - Nobel Peace Prize * Lasting Impact of a Remarkable Life Nansen‟s Youth * Fridtjof Nansen born near Christiania (now Oslo) Norway Oct. 10, 1861 * Name Fridtjof from saga of a daring Viking (Very fitting!) *Ancestor Hans Nansen, b. 1598, was sailor, Arctic explorer, mayor of Copenhagen * Father: lawyer, financier; strict parent * Mother: widow with 5 children – free-spirit - avid skier * Nansen skied across Norway to participate in a ski *In youth, he loved the competition in 1884, a remarkable feat noted by Norwegians. outdoors – skating, skiing, hiking, fishing Early Career/First Research Cruise * Entered Univ. of Christiania (Oslo) at age of 18 in 1880 * Chose zoology to do field work * First research cruise on working sealer Viking 1882 in Norwegian Sea * Did ocean and ice observations/ Fit in as excellent harpooner! * Vision of crossing Greenland! Nansen‟s First Job and His Ph D Work * Bergen Museum Curator at age of 20 in 1882 – lived with family that treated lepers * Studied nervous system of hag fish * Developed neuron theory for Ph. -

The Great Polar Controversy: D R Cook, Mt. Mckinley, And

THE GREAT POLAR CONTROVERSY: DR COOK, MT. MCKINLEY, AND THE QUEST FOR THE POLES Michael Sfraga College of Rural Alaska P.O. Box 756500 University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, Alaska 99775 Dennis Stephens Rasmuson Library P. 0. Box 756800 University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, Alaska 99775 ABSTRACT: In September 1906, Dr. Frederick A. Cook announced to a receptive public that he and Ed Barrill had successfully climbed Mt. McKinley by a "new route from the North." It was a time of keen interest in exploration, particularly of the Arctic and Antarctic regions. While Cook's was initially hailed as the first ascent of North America's highest mountain, his report came under increasing scrutiny as details came to light (or failed to come to light, as the case may be.) The controversy surrounding Cook's Mt. McKinley climb assumed increasing importance in the context of his claim to have been the first to reach the North Pole in April, 1908. The Doctor's claim was disputed by Robert E. Peary, who announced that he himself was first to the Pole in April, 1909, and that Cook "should not be taken too seriously." The chain of events that followed affected the course of exploration at both poles. This paper will examine the bases for Cook's claim to have been first on McKinley and first at the North Pole; the sequence of events that has led to general scepticism about Cook's claims; and the figures in Arctic and Antarctic exploration who were caught up in a dispute that continues to the current day. -

British Explorer Robert Falcon Scott Wrote in His Diary

“Another hard grind in the afternoon and five miles added,” British explorer Robert Falcon Scott wrote in his diary. “Our chance still holds good if we can put the work in, but it’s a terribly trying time.” It was mid-January 1912, and the 43-year-old Royal Navy officer was nearly 800 miles into a journey to one of the last unexplored places on the globe: the geographic South Pole. Scott’s five-man party had already endured brushes with blizzards and frostbite during their trek. They were now less than 80 miles from the finish line, but a single question still loomed over their progress: would they be the first group of men in history to reach the South Pole, or the second? Robert F. Scott and two of his four companions set out for the South Pole pulling a sled. Scott’s frozen ordeal had begun over a year earlier, when his ship Terra Nova had arrived on Ross Island in Antarctica’s McMurdo Sound. His 34-man shore party was tasked with conducting scientific research and collecting wildlife and rock samples, but Scott, who had previously led an Antarctic mission in 1902, was also determined to make a run at the Pole. Before leaving on the expedition, he had vowed “to reach the South Pole and to secure for the British Empire the honour of this achievement.” Scott’s mission was made all the more urgent by the knowledge that another explorer was seeking the Pole. Roald Amundsen was a 39- year-old Norwegian who had spent most of his life venturing to the far corners of the globe.