The Press, the Documentaries and the Byrd Archives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 18

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 18 Legends: Other This section contains a number of unrelated entries, including material about the oft-mentioned bell legends, the little people legends, and UFO legends. Some miscellaneous entries, arguably termed legends, include an entry about two Alaskan mountains named for Mt. Shasta, and an entry for the 1930s' slang phrase "From Mt. Shasta." Some of the materials exhibit a rare originality, especially Caroling's comic-book styled Mount Shasta and the Galaxy People. This section also includes a number of miscellaneous entries which in one way or another convey the mystic and spiritual expectations of some visitors to Mt. Shasta. The [MS number] indicates the Mount Shasta Special Collection accession numbers used by the College of the Siskiyous Library. [MS2156]. Avenell, Bruce K. Mount Shasta: The Vital Essence, A Spiritual Explorers Guide. Escondido: Eureka Society, 1999. 154 pp. Subtitle: To the Natural and Man-Made Consciousness-Enhancing Structures on Mt. Shasta The author recounts spiritual lessons and experiences from several decades of travel to Mount Shasta. Sand Flat, Grey Butte, Panther Meadows, etc, are described as special places. The author has a spiritual communication with a spiritual being named Duja, on Mt. Shasta and elsewhere. The book begins: 'A small group of very dedicated people, The Eureka Society has been coming to Mt. Shasta, California, for thirty years. They come to communicate with a spiritual being with whom many of them have had spiritual experiences while camping, hiking, and meditating on the mountain.' (p. ix). 'Although Duja, or any of the spirit beings on the mountain for that matter, may appear to be standing still she must have complete control of attitude, conscious focus, mental velocity and be monitoring the expenditure of energy necessary for you to see her. -

Strategia Del Governo Italiano Per L'artico

ITALY IN THE ARCTIC TOWARDS AN ITALIAN STRATEGY FOR THE ARCTIC NATIONAL GUIDELINES MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION 2015 1 ITALY IN THE ARCTIC 1. ITALY IN THE ARCTIC: MORE THAN A CENTURY OF HISTORY The history of the Italian presence in the Arctic dates back to 1899, when Luigi Amedeo di Savoia, Duke of the Abruzzi, sailed from Archangelsk with his ship (christened Stella Polare) to use the Franz Joseph Land as a stepping stone. The plan was to reach the North Pole on sleds pulled by dogs. His expedition missed its target, though it reached previously unattained latitudes. In 1926 Umberto Nobile managed to cross for the first time the Arctic Sea from Europe to Alaska, taking off from Rome together with Roald Amundsen (Norway) and Lincoln Ellsworth (USA) on the Norge airship (designed and piloted by Nobile). They were the first to reach the North Pole, where they dropped the three national flags. 1 Two years later Nobile attempted a new feat on a new airship, called Italia. Operating from Kings Bay (Ny-Ålesund), Italia flew four times over the Pole, surveying unexplored areas for scientific purposes. On its way back, the airship crashed on the ice pack north of the Svalbard Islands and lost nearly half of its crew. 2 The accident was linked to adverse weather, including a high wind blowing from the northern side of the Svalbard Islands to the Franz Joseph Land: this wind stream, previously unknown, was nicknamed Italia, after the expedition that discovered it. 4 Nobile’s expeditions may be considered as the first Italian scientific missions in the Arctic region. -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

Commission Meeting of NEW JERSEY GENERAL AVIATION STUDY COMMISSION

Commission Meeting of NEW JERSEY GENERAL AVIATION STUDY COMMISSION LOCATION: Committee Room 16 DATE: March 27, 1996 State House Annex 10:00 a.m. Trenton, New Jersey MEMBERS OF COMMISSION PRESENT: John J. McNamara Jr., Esq., Chairman Linda Castner Jack Elliott Philip W. Engle Peter S. Hines ALSO PRESENT: Robert B. Yudin (representing Gualberto Medina) Huntley A. Lawrence (representing Ben DeCosta) Kevin J. Donahue Office of Legislative Services Meeting Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, CN 068, Trenton, New Jersey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Dennis Yap DY Consultants representing Trenton-Robbinsville Airport 2 John F. Bickel, P.E. Township Engineer Oldmans Township, New Jersey 24 Kristina Hadinger, Esq. Township Attorney Montgomery Township, New Jersey 40 Donald W. Matthews Mayor Montgomery Township, New Jersey 40 Peter Rayner Township Administrator Montgomery Township, New Jersey 42 Patrick Reilly Curator Aviation Hall of Fame and Museum 109 Ronald Perrine Deputy Mayor Alexandria Township, New Jersey 130 Barry Clark Township Administrator/ Chief Financial Officer Readington Township, New Jersey 156 Benjamin DeCosta General Manager New Jersey Airports Port Authority of New York and New Jersey 212 APPENDIX: TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) Page “Township of Readington Resolution” submitted by Barry Clark 1x mjz: 1-228 (Internet edition 1997) PHILIP W. ENGLE (Member of Commission): While we are waiting for Jack McNamara, why don’t we call this meeting of the New Jersey General Aviation Study Commission to order. We will have a roll call. Abe Abuchowski? (no response) Assemblyman Richard Bagger? (no response) Linda Castner? (no response) Huntley Lawrence? Oh, he is on the way. -

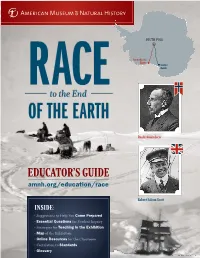

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001 “The Sensational Landscape: The History of Sensationalist Images of the Arctic, 1818-1910,” 2001. Supervisor: William Morrison UNBC Library call number: G630.G7 S74 2001 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the public perception of the Arctic through explorers’ journals and the modern press in America and Britain. The underlying question of this thesis is what exactly was the role of the press in forming public opinions about Arctic exploration in general? Did newspaper editors in America and Britain simply report what they found interesting based upon their own knowledge of Arctic explorers’ journals, or did these editors create that public interest in order to profit from increased sales? From a historical perspective, these reasons relate to the growth of an intellectual and social current that had been gaining strength on the Western World throughout the nineteenth century: the creation of the mythic hero. In essence, the mythical status of Arctic explorers developed in Britain, but was matured and honed in the American press, particularly in the competitive news industry in New York where the creation of the heroic Arctic explorer resulted largely from the vicious competitiveness of the contemporary press. Although the content of published Arctic exploration journals in the early nineteenth century did not change dramatically, the accuracy of those journals did. Exploration journals up until 1850 tended to focus heavily on the conventions of the sublime and picturesque to describe these new lands. However, these views were inaccurate, for these conventions forced the explorer to view the Arctic very much as they viewed the Swiss Alps or the English countryside. -

Number 90 RECORDS of ,THE UNITED STATES ANTARCTIC

~ I Number 90 RECORDS OF ,THE UNITED STATES ANTARCTIC SERVICE Compiled by Charles E. Dewing and Laura E. Kelsay j ' ·r-_·_. J·.. ; 'i The National Archives Nat i on a 1 A r c hive s and R e c o rd s S e r vi c e General Services~Administration Washington: 1955 ---'---- ------------------------ ------~--- ,\ PRELIMINARY INVENTORY OF THE RECORDS OF THE UNITED STATES ANTARCTIC SERVICE {Record Group 1 Z6) Compiled by Charles E. Dewing and Laura E. Kelsay The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1955 National Archives Publication No. 56-8 i\ FORENORD To analyze and describe the permanently valuable records of the Fed eral Government preserved in the National Archives Building is one of the main tasks of the National Archives. Various kinds of finding aids are needed to facilitate the use of these records, and the first step in the records-description program is the compilation of preliminary inventories of the material in the 270-odd record groups to which the holdings of the National Archives are allocated. These inventories are called "preliminary" because they are provisional in character. They are prepared.as soon as possible after the records are received without waiting to screen out all disposable material or to per fect the arrangement of the records. They are compiled primarily for in ternal use: both as finding aids to help the staff render efficient refer ence service and as a means of establishing administrative control over the records. Each preliminary inventory contains an introduction that briefly states the history and fUnctions of the agency that accumulated the records. -

WILKINS, ARCTIC EXPLORER, VISITS NAUGATUCK PLANT Senate Over-Rode Hie Veto of Gov

WILKINS, ARCTIC EXPLORER, VISITS NAUGATUCK PLANT Senate Over-Rode Hie Veto Of Gov. Cross Patients on Pan-American Orders Roosevelts Do Hartford, Conn, April 14—(UP) L. Cross. Special Bearing Up Bravely—As —The state senate today passed a The .roll call vote was 19 to 13, Danger List Observed Here bill taking away a power held by republicans voting solidly in favoi governors for 14 years of nominat- of the measure, which the governoi Rubber Outfits ing the New Haven city court judges had declared was raised because he No Change In Condition of Appropriate Exercises Held over the veto of Governor Wilbur Is a democrat. For His Crew Mrs Innes and at Wilby High School Carl Fries According to a proclamation is- sued by President Hoover, to-day Market Unsettled As Mrs Elizabeth Innes, 70, of Thom- has been set aside as Pan-American Sir Hubert, Who Will Attempt Underwater Trip to North aston, who was painfully burned day. At the regular weekly assemb- last Saturday noon at her home, ly at Wilby high school the pupils remained on the list of Miss session room Pole in Submarine Nautilus, Pays Trip to U. S. Rub= danger today Magoon's pre- Several *Issues Had at the Waterbury hospital. Owing sented a program In keeping with ber Company’s Borough Plant Yesterday to her age the chances of her re- the day. covering are not considered very The meeting was opened with the promising. singing of “America". The program to the Democrat.) North Pole, was Some Breaks (Special recently christened Carl Fries, 52, of 596 South Main which was presented included. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

99-00 May No. 4

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY 7338 Wayfarer Drive Fairfax Station, Virginia 22039 HONORARY PRESIDENT — MRS. PAUL A. SIPLE Vol. 99-00 May No. 4 Presidents: Dr. Carl R. Eklund, 1959-61 Dr. Paul A. Siple, 1961-62 Mr. Gordon D. Cartwright, 1962-63 BRASH ICE RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.), 1963-64 Mr. George R. Toney, 1964-65 Mr. Morton J. Rubin, 1965-66 Dr. Albert R Crary, 1966-68 As you can readily see, this newsletter is NOT announcing a speaker Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1968-70 program, as we have not lined anyone up, nor have any of you stepped Mr. George A. Doumani, 1970-71 Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1971-73 forward announcing your availability. So we are just moving out with a Mr. Peter F. Bermel, 1973-75 Dr. Kenneth J. Bertrand, 1975-77 newsletter based on some facts, some fiction, some fabrications. It will be Mrs. Paul A. Siple, 1977-78 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple, 1978-80 up to you to ascertain which ones are which. Good luck! Dr. Meredith F. Burrill, 1980-82 Dr. Mort D. Turner, 1982-84 Dr. Edward P. Todd, 1984-86 Two more Byrd men have been struck down -- Al Lindsey, the last of the Mr. Robert H. T. Dodson, 1986-88 Dr. Robert H. Rutford, 1988-90 Byrd scientists to die, and Steve Corey, Supply Officer, both of the 1933-35 Mr. Guy G. Guthridge, 1990-92 Byrd Antarctic Expedition. Al was a handsome man, and he and his wife, Dr. Polly A. Penhale, 1992-94 Mr. Tony K. Meunier, 1994-96 Elizabeth, were a stunning couple. -

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN Voyage Handbook

MS ROALD AMUNDSEN voyage handbook MS ROALD AMUNDSEN VOYAGE HANDBOOK 20192020 1 Dear Adventurer 2 Dear adventurer, Europe 4 Congratulations on booking make your voyage even more an extraordinary cruise on enjoyable. Norway 6 board our extraordinary new vessel, MS Roald Amundsen. This handbook includes in- formation on your chosen Svalbard 8 The ship’s namesake, Norwe- destination, as well as other gian explorer Roald Amund- destinations this ship visits Greenland 12 sen’s success as an explorer is during the 2019-2020 sailing often explained by his thor- season. We hope you will nd The Northwest Passage 16 ough preparations before this information inspiring. departure. He once said “vic- Contents tory awaits him who has every- We promise you an amazing Alaska 18 thing in order.” Being true to adventure! Amund sen’s heritage of good South America 20 planning, we encourage you to Welcome aboard for the ad- read this handbook. venture of a lifetime! Antarctica 24 It will provide you with good Your Hurtigruten Team Protecting the Antarctic advice, historical context, Environment from Invasive 28 practical information, and in- Species spiring information that will Environmental Commitment 30 Important Information 32 Frequently Asked Questions 33 Practical Information 34 Before and After Your Voyage Life on Board 38 MS Roald Amundsen Pack Like an Explorer 44 Our Team on Board 46 Landing by Small Boats 48 Important Phone Numbers 49 Maritime Expressions 49 MS Roald Amundsen 50 Deck Plan 2 3 COVER FRONT PHOTO: © HURTIGRUTEN © GREGORY SMITH HURTIGRUTEN SMITH GREGORY © COVER BACK PHOTO: © ESPEN MILLS HURTIGRUTEN CLIMATE Europe lies mainly lands and new trading routes. -

THE BALCHEN / POST AWARD for Excellence in the Performance of Airport Snow and Ice Control

^^^^^^ THE BALCHEN / POST AWARD for Excellence in the Performance of Airport Snow and Ice Control FOR EXCELLENCE IN THE PERFORMANCE OF AIRPORT SNOW & ICE CONTROL Once again the International Aviation Snow Symposium will sponsor the Balchen/Post Award for excellence in the performance of airport snow and ice control during the winter of 2020-2021 The awards will be presented to the personnel of the airport snow and ice control teams who have throughout this past winter demonstrated determination for excellence in their efforts to keep their airports open and safe. Download this application and submit in its entirety to There will be six awards - one to each of the winners in the following categories: COMMERCIAL AIRPORT MILITARY AIRPORT Providing scheduled service and holding a Part 139 certificate (The above airport classifications are for award selection purposes only) (not including a limited Part 139 certificate) Your assistance in helping select potential candidates worthy Large Over 200,000 scheduled operations annually of consideration is requested. A completed application for your Medium 100,000-200,000 scheduled operations annually airport should be submitted to the committee Small Less than 100,000 scheduled operations annually no later than April 30, 2021. Airports are encouraged to submit completed applications including GENERAL AVIATION AIRPORT their snow plan, airport layout plan and other supporting material before the deadline. Including limited Part 139 certificate airports Large 50,000 or more total operations annually The awards - six in total - are to be announced and presented virtually since our 2021 conference is Small Less than 50,000 operations annually cancelled SPONSORED BY THE NORTHEAST CHAPTER / AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF AIRPORT EXECUTIVES PAGE 1 BALCHEN/POST AWARD COMMITTEE P.O.