Robert Peary's North Polar Narratives and the Making of an American Icon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Arctic Nation a U.S

Connecting the United States to the Arctic OUR ARCTIC NATION A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative Cover Photo: Cover Photo: Hosting Arctic Council meetings during the U.S. Chairmanship gave the United States an opportunity to share the beauty of America’s Arctic state, Alaska—including this glacier ice cave near Juneau—with thousands of international visitors. Photo: David Lienemann, www. davidlienemann.com OUR ARCTIC NATION Connecting the United States to the Arctic A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Alabama . .2 14 Illinois . 32 02 Alaska . .4 15 Indiana . 34 03 Arizona. 10 16 Iowa . 36 04 Arkansas . 12 17 Kansas . 38 05 California. 14 18 Kentucky . 40 06 Colorado . 16 19 Louisiana. 42 07 Connecticut. 18 20 Maine . 44 08 Delaware . 20 21 Maryland. 46 09 District of Columbia . 22 22 Massachusetts . 48 10 Florida . 24 23 Michigan . 50 11 Georgia. 26 24 Minnesota . 52 12 Hawai‘i. 28 25 Mississippi . 54 Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. Photo: iStock.com 13 Idaho . 30 26 Missouri . 56 27 Montana . 58 40 Rhode Island . 84 28 Nebraska . 60 41 South Carolina . 86 29 Nevada. 62 42 South Dakota . 88 30 New Hampshire . 64 43 Tennessee . 90 31 New Jersey . 66 44 Texas. 92 32 New Mexico . 68 45 Utah . 94 33 New York . 70 46 Vermont . 96 34 North Carolina . 72 47 Virginia . 98 35 North Dakota . 74 48 Washington. .100 36 Ohio . 76 49 West Virginia . .102 37 Oklahoma . 78 50 Wisconsin . .104 38 Oregon. 80 51 Wyoming. .106 39 Pennsylvania . 82 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE AN ARCTIC NATION? oday, the Arctic region commands the world’s attention as never before. -

Of Penguins and Polar Bears Shapero Rare Books 93

OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS Shapero Rare Books 93 OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS EXPLORATION AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA +44 20 7493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com CONTENTS Antarctica 03 The Arctic 43 2 Shapero Rare Books ANTARCTIca Shapero Rare Books 3 1. AMUNDSEN, ROALD. The South Pole. An account of “Amundsen’s legendary dash to the Pole, which he reached the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912. before Scott’s ill-fated expedition by over a month. His John Murray, London, 1912. success over Scott was due to his highly disciplined dogsled teams, more accomplished skiers, a shorter distance to the A CORNERSTONE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION; THE ACCOUNT OF THE Pole, better clothing and equipment, well planned supply FIRST EXPEDITION TO REACH THE SOUTH POLE. depots on the way, fortunate weather, and a modicum of luck”(Books on Ice). A handsomely produced book containing ten full-page photographic images not found in the Norwegian original, First English edition. 2 volumes, 8vo., xxxv, [i], 392; x, 449pp., 3 folding maps, folding plan, 138 photographic illustrations on 103 plates, original maroon and all full-page images being reproduced to a higher cloth gilt, vignettes to upper covers, top edges gilt, others uncut, usual fading standard. to spine flags, an excellent fresh example. Taurus 71; Rosove 9.A1; Books on Ice 7.1. £3,750 [ref: 96754] 4 Shapero Rare Books 2. [BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION]. Grande 3. BELLINGSHAUSEN, FABIAN G. VON. The Voyage of Fete Venitienne au Parc de 6 a 11 heurs du soir en faveur de Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-1821. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001 “The Sensational Landscape: The History of Sensationalist Images of the Arctic, 1818-1910,” 2001. Supervisor: William Morrison UNBC Library call number: G630.G7 S74 2001 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the public perception of the Arctic through explorers’ journals and the modern press in America and Britain. The underlying question of this thesis is what exactly was the role of the press in forming public opinions about Arctic exploration in general? Did newspaper editors in America and Britain simply report what they found interesting based upon their own knowledge of Arctic explorers’ journals, or did these editors create that public interest in order to profit from increased sales? From a historical perspective, these reasons relate to the growth of an intellectual and social current that had been gaining strength on the Western World throughout the nineteenth century: the creation of the mythic hero. In essence, the mythical status of Arctic explorers developed in Britain, but was matured and honed in the American press, particularly in the competitive news industry in New York where the creation of the heroic Arctic explorer resulted largely from the vicious competitiveness of the contemporary press. Although the content of published Arctic exploration journals in the early nineteenth century did not change dramatically, the accuracy of those journals did. Exploration journals up until 1850 tended to focus heavily on the conventions of the sublime and picturesque to describe these new lands. However, these views were inaccurate, for these conventions forced the explorer to view the Arctic very much as they viewed the Swiss Alps or the English countryside. -

Chapter 5. Evelyn Briggs Baldwin and Operti Bay21

48 Chapter 5. Evelyn Briggs Baldwin and Operti Bay21 Amanda Lockerby Abstract During the second Wellman polar expedition, to Franz Josef Land in 1898, Wellman’s second- in-command, Evelyn Briggs Baldwin, gave the waters south of Cape Heller on the northwest of Wilczek Land the name ‘Operti Bay.’ Proof of this is found in Baldwin’s journal around the time of 16 September 1898. Current research indicates that Operti Bay was named after an Italian artist, Albert Operti. Operti’s membership in a New York City masonic fraternity named Kane Lodge, as well as correspondence between Baldwin and Rudolf Kersting, confirm that Baldwin and Operti engaged in a friendly relationship that resulted in the naming of the bay. Keywords Franz Josef Land, historic place names, historical geography, Evelyn Briggs Baldwin, Walter Wellman, Albert Operti, Operti Bay, polar exploration, Oslo NSF workshop DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/5.3582 Background Albert Operti was born in Turin Italy and educated in Ireland and Scotland and graduated from the Portsmouth Naval School before entering the British Marine Service. He soon returned to school to study art (see Freemasons, n.d.). He came to the United States where he served as a correspondent for the New York Herald in the 1890s who accompanied Robert Peary on two expeditions to Greenland. Artwork Operti was known for his depictions of the Arctic which included scenes from the history of exploration and the ships used in this exploration in the 19th century. He painted scenes from the search for Sir John Franklin, including one of the Royal Navy vessels Erebus and Terror under sail, as well as the abandonment of the American vessel Advance during Elisha Kent Kane’s Second Grinnell expedition. -

Missing Pacific Island Riddle Solved, Researcher Says 3 December 2012

Missing Pacific island riddle solved, researcher says 3 December 2012 "My supposition is that they simply recorded a hazard at the time. They might have recorded a low- lying reef or thought they saw a reef. They could have been in the wrong place. There is all number of possibilities," he said. "But what we do have is a dotted shape on the map that's been recorded at that time and it appears it's simply been copied over time." The supposed 'Sandy Island' as seen on Google Earth. A New Zealand researcher Monday claimed to have solved the riddle of a mystery South Pacific island shown on Google Earth and world maps which does not exist, blaming a whaling ship from 1876. The phantom landmass in the Coral Sea is shown as Sandy Island on Google Earth and Google maps and is supposedly midway between Australia and the French-governed New Caledonia. This November 22, 2012 photo illustration shows a computer screen displaying the Google Maps location of The Times Atlas of the World appears to identify it Sandy Island, which Australian scientists said last month as Sable Island, but according to Australian did not exist. It now appears to have been removed from scientists who went searching last month during a Google Maps. geological expedition it could not be found. Intrigued, Shaun Higgins, a researcher at Auckland Museum, started investigating and claimed it never News of the invisible island sparked debate on existed, with a whaling ship the source of the social media at the time, with tweeters pointing out original error. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

99-00 May No. 4

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY 7338 Wayfarer Drive Fairfax Station, Virginia 22039 HONORARY PRESIDENT — MRS. PAUL A. SIPLE Vol. 99-00 May No. 4 Presidents: Dr. Carl R. Eklund, 1959-61 Dr. Paul A. Siple, 1961-62 Mr. Gordon D. Cartwright, 1962-63 BRASH ICE RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.), 1963-64 Mr. George R. Toney, 1964-65 Mr. Morton J. Rubin, 1965-66 Dr. Albert R Crary, 1966-68 As you can readily see, this newsletter is NOT announcing a speaker Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1968-70 program, as we have not lined anyone up, nor have any of you stepped Mr. George A. Doumani, 1970-71 Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1971-73 forward announcing your availability. So we are just moving out with a Mr. Peter F. Bermel, 1973-75 Dr. Kenneth J. Bertrand, 1975-77 newsletter based on some facts, some fiction, some fabrications. It will be Mrs. Paul A. Siple, 1977-78 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple, 1978-80 up to you to ascertain which ones are which. Good luck! Dr. Meredith F. Burrill, 1980-82 Dr. Mort D. Turner, 1982-84 Dr. Edward P. Todd, 1984-86 Two more Byrd men have been struck down -- Al Lindsey, the last of the Mr. Robert H. T. Dodson, 1986-88 Dr. Robert H. Rutford, 1988-90 Byrd scientists to die, and Steve Corey, Supply Officer, both of the 1933-35 Mr. Guy G. Guthridge, 1990-92 Byrd Antarctic Expedition. Al was a handsome man, and he and his wife, Dr. Polly A. Penhale, 1992-94 Mr. Tony K. Meunier, 1994-96 Elizabeth, were a stunning couple. -

Elisha Kent Kane (1820-1857)

I78 ARCTIC PROFILES Elisha Kent Kane (1 820-1857) The first American arctic explorer of note, Elisha Kent Kane north up the west coast of Greenland to latitude 78”N, where was a man of broad interests and varied talents. Although he the Advunce was icebound and never released. Two of Kane’s died when he was only 37 years old, he distinguished himself crew continued by sled and on foot to 81 “22’N. “the northern- as a career naval officer, medical doctor, scientist, author, and mostland ever trodden by awhite man,” where they saw artist, and his death inspired a funeral procession by train from “open water stretching to the nothern horizon. The unending New Orleans to the home of his birth in Philadelphia. Eulogies shore line waswashed by shiningwaters without a sign of hailed Kane as America’s “Arctic Columbus”. ice.” Kane, believing this to’be the scientific culmination of theirjourney, declared: “The great North Sea, the Polynia has Well-travelled prior to his mid-century arctic voyages, Kane been reached.” had journeyed through South America, Africa, Europe, and the Far East. Small of stature and physically frail as a result of By the spring of 1855, after three bummers and two winters a rheumatica ‘heart, the naval doctor neverthelesssought that proved far harsher and more impoverished than the men’s challenges of physical endurance, which led to his volunteer- most pessimistic fears, Kane and his crew faced imminent star- ing for the arduous U.S. polar expedition in 1850 as ship’s vation. Consequentunrest and disloyalty, coupledwith the surgeon and again in 1853 as leader. -

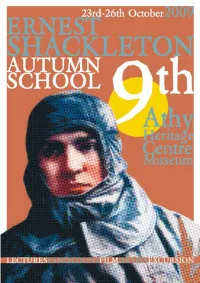

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Shackleton Born close to the village of Kilkea, FRIDAY 23rd October between Castledermot and Athy, in the south of County Kildare in 1874, Ernest Shackleton Official Opening & is renowned for his courage, his commitment to the welfare of his comrades and his Book Launch immense contribution to exploration and 7.30pm in Athy Heritage Centre - geographical discovery. The Shackleton family Museum first came to south Kildare in the early years of the eighteenth century. Ernest’s Quaker In association with the Erskine Press the forefather, Abraham Shackleton, established a multi-denominational school in the village school will host the launch of Regina Daly’s of Ballitore. This school was to educate such book notable figures as Napper Tandy, Edmund ‘The Shackleton Letters: Behind the Scenes of Burke, Cardinal Paul Cullen and Shackleton’s the Nimrod Expedition’. great aunt, the Quaker writer, Mary Leadbeater. Apart from their involvement in education, the extended family was also deeply involved in Shackleton the business and farming life of south Kildare. Having gone to sea as a teenager, Memorial Lecture Shackleton joined Captain Scott’s Discovery expedition (1901 – 1904) and, in time, was by Caroline Casey to lead three of his own expeditions to the Antarctic. His Endurance expedition (1914 – 8.15pm in Athy Heritage Centre - Museum 1916) has become known as one of the great epics of human survival. He died in 1922, at The founder and CEO of Kanchi (formerly South Georgia, on his fourth expedition to the known as The Aisling Foundation) Caroline is Antarctic, and – on his wife’s instructions – was buried there. -

Expedition Periodicals: a Chronological List

Appendix: Expedition Periodicals: A Chronological List by David H. Stam [Additions and corrections are welcome at [email protected]] THE FOLLOWING LIST provides the date, the periodical name, the setting (ship or other site), the expedition leader, the expedition name when assigned, and, as available, format and publication information. 1819–20. North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle. Hecla and Griper. William Edward Parry. British Northwest Passage Expedition. Manuscript, printed in London in 1821 with a second edition that same year (London: John Murray, 1821). Biweekly (21 issues). 1845–49. Name, if any, unknown. Terror and Erebus. Sir John Franklin. Both ships presumably had printing facilities for publishing a ship’s newspaper but no trace of one survives. [Not to be included in this list is the unpublished The Arctic Spectator & North Devon Informer, dated Monday, November 24, 1845, a completely fictional printed newssheet, invented for the Franklin Expedition by Professor Russell Potter, Rhode Island College. Only two pages of a fictional facsimile have been located.] 1850–51. Illustrated Arctic News. Resolute. Horatio Austin. Manuscript with illustrations, the latter published as Facsimile of the Illustrated Arctic News. Published on Board H.M.S. Resolute, Captn. Horatio T. Austin (London: Ackermann, 1852). Monthly. Five issues included in the facsimile. 1850–51. Aurora Borealis. Assistance. Erasmus Ommaney. Manuscript, from which selected passages were published in Arctic Miscellanies: A Souvenir of the Late Polar Search (London: Colburn and Co., 1852). Monthly. Albert Markham was aboard Assistance and was also involved in the Minavilins, a more covert paper on the Assistance which, like its Resolute counterpart, The Gleaner, was confiscated and suppressed altogether. -

FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE EARLY MAPS 99298 IMCOS Covers 2012 Layout 1 06/02/2012 09:45 Page 5

IMCSJOURNAL S pr ing 2013 | Number 132 FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE EARLY MAPS 99298 IMCOS covers 2012_Layout 1 06/02/2012 09:45 Page 5 THE MAP HOUSE OF LONDON (established 1907) Antiquarian Maps, Atlases, Prints & Globes 54 BEAUCHAMP PLACE KNIGHTSBRIDGE LONDON SW3 1NY Telephone: 020 7589 4325 or 020 7584 8559 Fax: 020 7589 1041 Email: [email protected] www.themaphouse.com JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL MAP COLLECTORS’ SOCIETY FOUNDED S pr ing 2013 | Number 132 1980 FEATURES Mercator and his ‘Atlas of Europe’ 13 Self-protection, official obligations and the pursuit of truth Peter Barber High in the Andes partii 25 Further adventures of the French Academy expedition to Peru Richard Smith ‘The Dutch colony of The Cape of Good Hope’ 30 A map by L.S. De la Rochette Roger Stewart REGULAR ITEMS A Letter from the Chairman 3 Hans Kok From the Editor’s Desk 5 Ljiljana Ortolja-Baird IMCoS Matters 7 Mapping Matters 37 Worth a Look 46 You Write to Us 49 Book Reviews 53 Copy and other material for our next issue (Summer 2013) should be submitted by 1 April 2013. Editorial items should be sent to the Editor Ljiljana Ortolja-Baird, email [email protected] or 14 Hallfield, Quendon, Essex CB11 3XY United Kingdom Consultant Editor Valerie Newby Designer Catherine French Advertising Jenny Harvey, 27 Landford Road, Putney, London SW15 1AQ United Kingdom Tel +44 (0)20 8789 7358, email [email protected] Please note that acceptance of an article for publication gives IMCoS the right to place it on our website.