Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001 “The Sensational Landscape: The History of Sensationalist Images of the Arctic, 1818-1910,” 2001. Supervisor: William Morrison UNBC Library call number: G630.G7 S74 2001 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the public perception of the Arctic through explorers’ journals and the modern press in America and Britain. The underlying question of this thesis is what exactly was the role of the press in forming public opinions about Arctic exploration in general? Did newspaper editors in America and Britain simply report what they found interesting based upon their own knowledge of Arctic explorers’ journals, or did these editors create that public interest in order to profit from increased sales? From a historical perspective, these reasons relate to the growth of an intellectual and social current that had been gaining strength on the Western World throughout the nineteenth century: the creation of the mythic hero. In essence, the mythical status of Arctic explorers developed in Britain, but was matured and honed in the American press, particularly in the competitive news industry in New York where the creation of the heroic Arctic explorer resulted largely from the vicious competitiveness of the contemporary press. Although the content of published Arctic exploration journals in the early nineteenth century did not change dramatically, the accuracy of those journals did. Exploration journals up until 1850 tended to focus heavily on the conventions of the sublime and picturesque to describe these new lands. However, these views were inaccurate, for these conventions forced the explorer to view the Arctic very much as they viewed the Swiss Alps or the English countryside. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

Rather Than Imposing Thematic Unity Or Predefining a Common Theoretical

The Supernatural Arctic: An Exploration Shane McCorristine, University College Dublin Abstract The magnetic attraction of the North exposed a matrix of motivations for discovery service in nineteenth-century culture: dreams of wealth, escape, extreme tourism, geopolitics, scientific advancement, and ideological attainment were all prominent factors in the outfitting expeditions. Yet beneath this „exoteric‟ matrix lay a complex „esoteric‟ matrix of motivations which included the compelling themes of the sublime, the supernatural, and the spiritual. This essay, which pivots around the Franklin expedition of 1845-1848, is intended to be an exploration which suggests an intertextuality across Arctic time and geography that was co-ordinated by the lure of the supernatural. * * * Introduction In his classic account of Scott‟s Antarctic expedition Apsley Cherry- Garrard noted that “Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time which has been devised”.1 If there is one single question that has been asked of generations upon generations of polar explorers it is, Why?: Why go through such ordeals, experience such hardship, and take such risks in order to get from one place on the map to another? From an historical point of view, with an apparent fifty per cent death rate on polar voyages in the long nineteenth century amid disaster after disaster, the weird attraction of the poles in the modern age remains a curious fact.2 It is a less curious fact that the question cui bono? also featured prominently in Western thinking about polar exploration, particularly when American expeditions entered the Arctic 1 Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World. -

Annual Report FY15: July 1, 2014–June 30, 2015

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC Annual Report Fiscal Year 2015 COA Development Office College of the Atlantic 105 Eden Street Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 Dean of Institutional Advancement Lynn Boulger 207-801-5620, [email protected] Development Associate Amanda Ruzicka Mogridge 207-801-5625, [email protected] Development Officer Kristina Swanson 207-801-5621, [email protected] Alumni Relations/Development Coordinator Dianne Clendaniel 207-801-5624, [email protected] Manager of Donor Engagement Jennifer Hughes 207-801-5622, [email protected] Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in preparing all donor lists for this annual report. If a mistake has been made in your name, or if your name was omitted, we apologize. Please notify the development office at 207-801-5625 with any changes. www.coa.edu/support COA ANNUAL REPorT FY15: July 1, 2014–June 30, 2015 I love nothing more than telling stories of success and good news about our We love to highlight the achievements of our students, and one that stands out incredible college. One way I tell these stories is through a series I’ve created for from last year is the incredible academic recognition given to Ellie Oldach '15 our Board of Trustees called the College of the Atlantic Highlight Reel. A perusal of when she received a prestigious Fulbright Research Scholarship. It was the first the Reels from this year include the following elements: time in the history of the college that a student has won a Fulbright. Ellie is spending ten months on New Zealand’s South Island working to understand and COA received the 2014 Honor Award from Maine Preservation for our model coastal marsh and mussel bed communities. -

The North Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: an Historical Perspective

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State History Theses History and Social Studies Education 12-2011 The orN th Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective Kayla J. Shypski [email protected] Advisor Dr. Cynthia A. Conides First Reader Cynthia A. Conides, Ph.D., Associate Professor of History and Social Studies Education, Director of Museum Studies Second Reader Lisa Marie Anselmi, Ph.D., R.P.A., Associate Professor and Chair of the Anthropology Department Department Chair Andrew D. Nicholls To learn more about the History and Social Studies Education Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://history.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Shypski, Kayla J., "The orN th Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective" (2011). History Theses. Paper 2. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons i ABSTRACT OF THESIS The North Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective Polar exploration was a large part of American culture and society during the mid to late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. The North Pole controversy of 1909 in which two American Arctic explorers both claimed to have reached the North Pole was a culmination of the polar exploration era. However, one aspect of the polar expeditions that is relatively unknown is the treatment of the native Inuit peoples of the Arctic by the polar explorers. -

Roald Amundsen Essay Prepared for the Encyclopedia of the Arctic by Jonathan M

Roald Amundsen Essay prepared for The Encyclopedia of the Arctic By Jonathan M. Karpoff No polar explorer can lay claim to as many major accomplishments as Roald Amundsen. Amundsen was the first to navigate a Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the first to reach the South Pole, and the first to lay an undisputed claim to reaching the North Pole. He also sailed the Northeast Passage, reached a farthest north by air, and made the first crossing of the Arctic Ocean. Amundsen also was an astute and respectful ethnographer of the Netsilik Inuits, leaving valuable records and pictures of a two-year stay in northern Canada. Yet he appears to have been plagued with a public relations problem, regarded with suspicion by many as the man who stole the South Pole from Robert F. Scott, constantly having to fight off creditors, and never receiving the same adulation as his fellow Norwegian and sometime mentor, Fridtjof Nansen. Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was born July 16, 1872 in Borge, Norway, the youngest of four brothers. He grew up in Oslo and at a young age was fascinated by the outdoors and tales of arctic exploration. He trained himself for a life of exploration by taking extended hiking and ski trips in Norway’s mountains and by learning seamanship and navigation. At age 25, he signed on as first mate for the Belgica expedition, which became the first to winter in the south polar region. Amundsen would form a lifelong respect for the Belgica’s physician, Frederick Cook, for Cook’s resourcefulness in combating scurvy and freeing the ship from the ice. -

Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott: Amundsen’S Earlier Voyages and Experience

Roald Amundsen and Robert Scott: Amundsen’s earlier voyages and experience. • Roald Amundsen joined the Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–99) as first mate. • This expedition, led by Adrien de Gerlache using the ship the RV Belgica, became the first expedition to winter in Antarctica. Voyage in research vessel Belgica. • The Belgica, whether by mistake or design, became locked in the sea ice at 70°30′S off Alexander Island, west of the Antarctic Peninsula. • The crew endured a winter for which they were poorly prepared. • RV Belgica frozen in the ice, 1898. Gaining valuable experience. • By Amundsen's own estimation, the doctor for the expedition, the American Frederick Cook, probably saved the crew from scurvy by hunting for animals and feeding the crew fresh meat • In cases where citrus fruits are lacking, fresh meat from animals that make their own vitamin C (which most do) contains enough of the vitamin to prevent scurvy, and even partly treat it. • This was an important lesson for Amundsen's future expeditions. Frederick Cook с. 1906. Another successful voyage. • In 1903, Amundsen led the first expedition to successfully traverse Canada's Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. • He planned a small expedition of six men in a 45-ton fishing vessel, Gjøa, in order to have flexibility. Gjøa today. Sailing westward. • His ship had relatively shallow draft. This was important since the depth of the sea was about a metre in some places. • His technique was to use a small ship and hug the coast. Amundsen had the ship outfitted with a small gasoline engine. -

Chapter 8: Surface and Deep Circulation Exploring the World

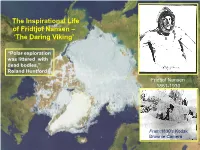

The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ “Polar exploration was littered with dead bodies,” Roland Huntford Fridtjof Nansen 1861-1930 Fram:1890’s Kodak Brownie Camera The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen – „The Daring Viking‟ Events of Period U.S. Civil War 1861-1865 2nd Industrial Rev. 1880‟s Fridtjof Nansen World War I 1861-1930 1914-1918 League of Nations 1919 Rise of Bolshevism 1920‟s Fram:1890’s Kodak Brownie Camera The Inspirational Life of Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930) * Nansen‟s Youth * Education/Sportsman * Early Career Accomplishments * First Research Cruise * Greenland Crossing * Farthest North and Accolades * More Oceanographic Research * Statesman and Diplomat * Humanitarian - Nobel Peace Prize * Lasting Impact of a Remarkable Life Nansen‟s Youth * Fridtjof Nansen born near Christiania (now Oslo) Norway Oct. 10, 1861 * Name Fridtjof from saga of a daring Viking (Very fitting!) *Ancestor Hans Nansen, b. 1598, was sailor, Arctic explorer, mayor of Copenhagen * Father: lawyer, financier; strict parent * Mother: widow with 5 children – free-spirit - avid skier * Nansen skied across Norway to participate in a ski *In youth, he loved the competition in 1884, a remarkable feat noted by Norwegians. outdoors – skating, skiing, hiking, fishing Early Career/First Research Cruise * Entered Univ. of Christiania (Oslo) at age of 18 in 1880 * Chose zoology to do field work * First research cruise on working sealer Viking 1882 in Norwegian Sea * Did ocean and ice observations/ Fit in as excellent harpooner! * Vision of crossing Greenland! Nansen‟s First Job and His Ph D Work * Bergen Museum Curator at age of 20 in 1882 – lived with family that treated lepers * Studied nervous system of hag fish * Developed neuron theory for Ph. -

The Great Polar Controversy: D R Cook, Mt. Mckinley, And

THE GREAT POLAR CONTROVERSY: DR COOK, MT. MCKINLEY, AND THE QUEST FOR THE POLES Michael Sfraga College of Rural Alaska P.O. Box 756500 University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, Alaska 99775 Dennis Stephens Rasmuson Library P. 0. Box 756800 University of Alaska Fairbanks Fairbanks, Alaska 99775 ABSTRACT: In September 1906, Dr. Frederick A. Cook announced to a receptive public that he and Ed Barrill had successfully climbed Mt. McKinley by a "new route from the North." It was a time of keen interest in exploration, particularly of the Arctic and Antarctic regions. While Cook's was initially hailed as the first ascent of North America's highest mountain, his report came under increasing scrutiny as details came to light (or failed to come to light, as the case may be.) The controversy surrounding Cook's Mt. McKinley climb assumed increasing importance in the context of his claim to have been the first to reach the North Pole in April, 1908. The Doctor's claim was disputed by Robert E. Peary, who announced that he himself was first to the Pole in April, 1909, and that Cook "should not be taken too seriously." The chain of events that followed affected the course of exploration at both poles. This paper will examine the bases for Cook's claim to have been first on McKinley and first at the North Pole; the sequence of events that has led to general scepticism about Cook's claims; and the figures in Arctic and Antarctic exploration who were caught up in a dispute that continues to the current day. -

British Explorer Robert Falcon Scott Wrote in His Diary

“Another hard grind in the afternoon and five miles added,” British explorer Robert Falcon Scott wrote in his diary. “Our chance still holds good if we can put the work in, but it’s a terribly trying time.” It was mid-January 1912, and the 43-year-old Royal Navy officer was nearly 800 miles into a journey to one of the last unexplored places on the globe: the geographic South Pole. Scott’s five-man party had already endured brushes with blizzards and frostbite during their trek. They were now less than 80 miles from the finish line, but a single question still loomed over their progress: would they be the first group of men in history to reach the South Pole, or the second? Robert F. Scott and two of his four companions set out for the South Pole pulling a sled. Scott’s frozen ordeal had begun over a year earlier, when his ship Terra Nova had arrived on Ross Island in Antarctica’s McMurdo Sound. His 34-man shore party was tasked with conducting scientific research and collecting wildlife and rock samples, but Scott, who had previously led an Antarctic mission in 1902, was also determined to make a run at the Pole. Before leaving on the expedition, he had vowed “to reach the South Pole and to secure for the British Empire the honour of this achievement.” Scott’s mission was made all the more urgent by the knowledge that another explorer was seeking the Pole. Roald Amundsen was a 39- year-old Norwegian who had spent most of his life venturing to the far corners of the globe. -

Richard E. Byrd and the North Pole Fzight of 1926: Fact, Fiction As Fact, and Interpretation

RICHARD E. BYRD AND THE NORTH POLE FZIGHT OF 1926: FACT, FICTION AS FACT, AND INTERPRETATION Raimund E. Goerler Byrd Polar Research Center The Ohio State University 2700 Kenny Road Columbus, Ohio 432 10 USA ABSTRACT: On May 9, 1926, Richard E. Byrd announced that he and co-pilot Floyd Bennett were the fust to fly an airplane over the North Pole. That claim made Byrd an international hero, established him as a pivotal figure in polar exploration and in aerial navigation, and set the stage for Byrd's flight over the South Pole in 1929 and his leadership and participation in five expeditions to Antarctica before his death in 1957. Byrd's claim to the North Pole in 1926 has aroused controversy. Some critics scoffed that hls plane did not have the speed to have reached the Pole in the time he reported. One book even charged that Byrd had merely circled in the horizon out of sight of reporters and then announced his achievement. Three days after Byrd's claim, Roald Amundsen, Lincoh Ellsworth, Umberto Nobile and an international crew aboard the airship Norge flew over the Pole in a trans-Arctic crossing. In 1996, the announcement and discovery of Byrd's diary of the fight in 1926 renewed the debate about Byrd's claim to the North Pole. This presentation reviews the controversy, the diary, which was recently published (To the Pole: The Dialy and Notebook of Richard E. Byrd 1925-1927 (Columbus, Ohio: the Ohio State University Press, 1998), interpretations of the diary, and the records of Byrd's first expedition in the Papers of Admiral Richard E. -

Ghosts of Cape Sabine: the Harrowing True Story of the Greely

REVIEWS • 317 GHOSTS OF CAPE SABINE: THE HARROWING TRUE Howgate’s breezy assertions were particularly fateful in STORY OF THE GREELY EXPEDITION. By light of later events. First, the experiences of Charles LEONARD F. GUTTRIDGE. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Francis Hall in 1871 and Nares in 1875–76 had led Sons, 2000. 354 p., maps, b&w illus., notes, bib., index. Howgate to conclude that Lady Franklin Bay could reliably Hardbound. Cdn$37.99. be reached by ship every summer. Second, he believed that ships were undesirable “cities of refuge” that hindered Depending on their personalities, explorers have always proper adaptation to the Arctic. The polar colony, he made a choice between pursuing dramatic geographical proposed, should be transported by ship, left with adequate discoveries or doing quiet, competent scientific work. supplies, and picked up three years later (Howgate, 1879). Some tried to play both sides, but the conservative ones Howgate’s optimism seemed well founded when the could never quite match the dash of the sensation-seek- Proteus, a refitted whaling ship, left the 25 men of the ers—who, for their part, feigned scientific aspirations but Greely expedition at Lady Franklin Bay in August 1881. A brought back few solid results. In the High Arctic, Robert ship was to bring mail and supplies the following summer, Peary and Elisha Kent Kane are classic examples of the and the pickup was scheduled for 1883. Adolphus Greely, melodramatic explorer, while Otto Sverdrup exemplifies an ambitious Signal Corps lieutenant who had done well the ideal leader of a nineteenth-century scientific team.