Arctic Exploration in British Print Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001

Stevenson-Waldie, Laura. 2001 “The Sensational Landscape: The History of Sensationalist Images of the Arctic, 1818-1910,” 2001. Supervisor: William Morrison UNBC Library call number: G630.G7 S74 2001 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of the public perception of the Arctic through explorers’ journals and the modern press in America and Britain. The underlying question of this thesis is what exactly was the role of the press in forming public opinions about Arctic exploration in general? Did newspaper editors in America and Britain simply report what they found interesting based upon their own knowledge of Arctic explorers’ journals, or did these editors create that public interest in order to profit from increased sales? From a historical perspective, these reasons relate to the growth of an intellectual and social current that had been gaining strength on the Western World throughout the nineteenth century: the creation of the mythic hero. In essence, the mythical status of Arctic explorers developed in Britain, but was matured and honed in the American press, particularly in the competitive news industry in New York where the creation of the heroic Arctic explorer resulted largely from the vicious competitiveness of the contemporary press. Although the content of published Arctic exploration journals in the early nineteenth century did not change dramatically, the accuracy of those journals did. Exploration journals up until 1850 tended to focus heavily on the conventions of the sublime and picturesque to describe these new lands. However, these views were inaccurate, for these conventions forced the explorer to view the Arctic very much as they viewed the Swiss Alps or the English countryside. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

99-00 May No. 4

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY 7338 Wayfarer Drive Fairfax Station, Virginia 22039 HONORARY PRESIDENT — MRS. PAUL A. SIPLE Vol. 99-00 May No. 4 Presidents: Dr. Carl R. Eklund, 1959-61 Dr. Paul A. Siple, 1961-62 Mr. Gordon D. Cartwright, 1962-63 BRASH ICE RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.), 1963-64 Mr. George R. Toney, 1964-65 Mr. Morton J. Rubin, 1965-66 Dr. Albert R Crary, 1966-68 As you can readily see, this newsletter is NOT announcing a speaker Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1968-70 program, as we have not lined anyone up, nor have any of you stepped Mr. George A. Doumani, 1970-71 Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1971-73 forward announcing your availability. So we are just moving out with a Mr. Peter F. Bermel, 1973-75 Dr. Kenneth J. Bertrand, 1975-77 newsletter based on some facts, some fiction, some fabrications. It will be Mrs. Paul A. Siple, 1977-78 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple, 1978-80 up to you to ascertain which ones are which. Good luck! Dr. Meredith F. Burrill, 1980-82 Dr. Mort D. Turner, 1982-84 Dr. Edward P. Todd, 1984-86 Two more Byrd men have been struck down -- Al Lindsey, the last of the Mr. Robert H. T. Dodson, 1986-88 Dr. Robert H. Rutford, 1988-90 Byrd scientists to die, and Steve Corey, Supply Officer, both of the 1933-35 Mr. Guy G. Guthridge, 1990-92 Byrd Antarctic Expedition. Al was a handsome man, and he and his wife, Dr. Polly A. Penhale, 1992-94 Mr. Tony K. Meunier, 1994-96 Elizabeth, were a stunning couple. -

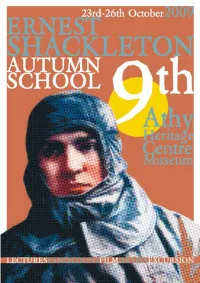

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Shackleton Born close to the village of Kilkea, FRIDAY 23rd October between Castledermot and Athy, in the south of County Kildare in 1874, Ernest Shackleton Official Opening & is renowned for his courage, his commitment to the welfare of his comrades and his Book Launch immense contribution to exploration and 7.30pm in Athy Heritage Centre - geographical discovery. The Shackleton family Museum first came to south Kildare in the early years of the eighteenth century. Ernest’s Quaker In association with the Erskine Press the forefather, Abraham Shackleton, established a multi-denominational school in the village school will host the launch of Regina Daly’s of Ballitore. This school was to educate such book notable figures as Napper Tandy, Edmund ‘The Shackleton Letters: Behind the Scenes of Burke, Cardinal Paul Cullen and Shackleton’s the Nimrod Expedition’. great aunt, the Quaker writer, Mary Leadbeater. Apart from their involvement in education, the extended family was also deeply involved in Shackleton the business and farming life of south Kildare. Having gone to sea as a teenager, Memorial Lecture Shackleton joined Captain Scott’s Discovery expedition (1901 – 1904) and, in time, was by Caroline Casey to lead three of his own expeditions to the Antarctic. His Endurance expedition (1914 – 8.15pm in Athy Heritage Centre - Museum 1916) has become known as one of the great epics of human survival. He died in 1922, at The founder and CEO of Kanchi (formerly South Georgia, on his fourth expedition to the known as The Aisling Foundation) Caroline is Antarctic, and – on his wife’s instructions – was buried there. -

THE STANDARD CHARTERED TRANS-ANTARCTIC WINTER EXPEDITION SUPPORTED by the COMMONWEALTH the Coldest Journey on Earth

THE STANDARD CHARTERED TRANS-ANTARCTIC WINTER EXPEDITION SUPPORTED BY THE COMMONWEALTH The Coldest Journey On Earth PATRON: HRH THE PRINCE OF WALES, CHAIRMAN: Tony Medniuk, DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Gavin Laws (Standard Chartered Bank), SCIENCE COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN: Sir Peter Williams CBE FRS FREng, SCIENCE COMMITTEE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Prof Dougal Goodman FREng, EXPEDITION ORGANISER & LEADER: Sir Ranulph Fiennes Bt OBE, MARINE ORGANISER: Anton Bowring, COMMONWEALTH LIAISON: Derek Smail, EXPEDITION POLAR PLANNER: Martin Bell, EXPEDITION POLAR CONSULTANT: Jim McNeill, INTERACTIVE EDUCATIONAL WEBSITE DIRECTOR/MICROSOFT LIAISON: Phil Hodgson (Durham's Education Development Service), EXTREME COLD TEMPERATURE EQUIPMENT: Steven Holland and Team, SPONSOR LIAISON: Eric Reynolds The TAWT TRUST Ltd (UK Registered Charity 7424188) CHAIRMAN: Tony Medniuk, DEPUTY CHAIRMAN: Gavin Laws; Michael Payton, Richard Jackson, Alan Tasker, Anton Bowring, Sir Ranulph Fiennes Bt OBE IN CONFIDENCE EXPEDITION AIMS AND OUTLINE SCHEDULE 1. OVERALL The aim of the TAWT Expedition is to complete the first historic crossing of the Antarctic Continent, to raise over £10 million for our charity SEEING IS BELIEVING, to educate school children, and to complete our science programme. In order not to alert other polar groups, such as our long-time rivals in Norway, we will only announce the Expedition when we are 100% ready to go! The earliest date that we could leave the UK will be 1 October 2012. The alternate date, given any unforeseen delay, will be 1 October 2013. Relevant Antarctic Records 1902 First Penetration of the unknown continent : Scott/Shackleton/Wilson (Brit) 1908 First Penetration of Inland icecap : Shackleton/Wilde/Marshall/?+1 (Brit) 1911 First to reach South Pole : Amundsen + 4 skiers (Norwegian) 1950s First 2-way-pincer Crossing of Antarctica. -

Rather Than Imposing Thematic Unity Or Predefining a Common Theoretical

The Supernatural Arctic: An Exploration Shane McCorristine, University College Dublin Abstract The magnetic attraction of the North exposed a matrix of motivations for discovery service in nineteenth-century culture: dreams of wealth, escape, extreme tourism, geopolitics, scientific advancement, and ideological attainment were all prominent factors in the outfitting expeditions. Yet beneath this „exoteric‟ matrix lay a complex „esoteric‟ matrix of motivations which included the compelling themes of the sublime, the supernatural, and the spiritual. This essay, which pivots around the Franklin expedition of 1845-1848, is intended to be an exploration which suggests an intertextuality across Arctic time and geography that was co-ordinated by the lure of the supernatural. * * * Introduction In his classic account of Scott‟s Antarctic expedition Apsley Cherry- Garrard noted that “Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time which has been devised”.1 If there is one single question that has been asked of generations upon generations of polar explorers it is, Why?: Why go through such ordeals, experience such hardship, and take such risks in order to get from one place on the map to another? From an historical point of view, with an apparent fifty per cent death rate on polar voyages in the long nineteenth century amid disaster after disaster, the weird attraction of the poles in the modern age remains a curious fact.2 It is a less curious fact that the question cui bono? also featured prominently in Western thinking about polar exploration, particularly when American expeditions entered the Arctic 1 Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

Who Is Sir Ranulph Fiennes?

Who Is Sir Ranulph Fiennes? Sir Ranulph Fiennes is a British expedition leader who has broken world records, won many awards and completed expeditions on a range of different modes of transport. These include hovercraft, riverboat, manhaul sledge, snowmobile, skis and a four-wheel drive vehicle. He is also the only living person who has travelled around the Earth’s circumpolar surface. Did You Know…? Circumpolar means Sir Ranulph does not call himself to go around the an explorer as he says he has only Earth’s North Pole once mapped an unknown area. and South Pole. The Beginning of an Expedition Leader Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes was born on 7th March 1944 in Windsor, UK. His father was killed during the Second World War and after the war, Ranulph’s mother moved the family to South Africa. He lived there until he was 12 years old. He returned to the UK where he continued his education, later attending Eton College. Ranulph joined the British army, where he served for eight years in the same regiment that his father had served in, the Royal Scots Greys. While in the army, Ranulph taught soldiers how to ski and canoe. After leaving the army, Ranulph and his wife decided to earn money by leading expeditions. A World of Expeditions North Pole Arctic Mount Everest The Eiger The River Nile South Pole Antarctic The Transglobe Expedition In 1979, Ranulph, his wife Ginny and friends Charles Burton and Oliver Shepherd embarked on an expedition to the Antarctic which was planned by Ginny, an explorer in her own right. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

Brilliant Ideas to Get Your Students Thinking Creatively About Polar

FOCUS ON SHACKLETON Brilliant ideas to get your students thinking creatively about polar exploration, with links across a wide range of subjects including maths, art, geography, science and literacy. WHAT? WHERE? WHEN? WHO? AURORA AUSTRALIS This book was made in the Antarctic by Shackleton’s men during the winter of 1908. It contains poems, accounts, stories, pictures and entertainment all written by the men during the 1907-09 Nimrod expedition. The copy in our archive has a cover made from pieces of packing crates. The book is stitched with green silk cord thread and held together with a spine made from seal skin. The title and the penguin stamp were glued on afterwards. DID YOU KNOW? To entertain the men during the long, cold winter months of the Nimrod Expedition, Shackleton packed a printing press. Before the expedition set off Ernest Joyce and Frank Wild received training in typesetting and printing. In the hut at Cape Royds the men wrote and practised their printing techniques. All through the winter different men wrote pieces for the book. The expedition artist, George Marston, produced the illustrations. Bernard Day constructed the book using packing crates that had stored butter. This was the first book to be published in the Antarctic. SHORT FILMS ABOUT ANTARCTICA: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/resources Accession number: MS 722;EN – Dimensions: height: 270mm, width 210mm, depth: 30mm MORE CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/resources HIGH RESOLUTION IMAGE: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/resources This object is part of the collection at the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge ̶ see more online at: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/collections ACTIVITY IDEAS FOR THE CLASSROOM Visit our website for a high resolution image of this object and more: www.spri.cam.ac.uk/museum/resources BACKGROUND ACTIVITY IDEA RESOURCES CURRICULUM LINKS Aurora Australis includes lots of accounts, As a class discuss events that you have all experienced - a An example of an account, poem LITERACY different styles of writing, stories and poems written by the men. -

Annual Report FY15: July 1, 2014–June 30, 2015

COLLEGE OF THE ATLANTIC Annual Report Fiscal Year 2015 COA Development Office College of the Atlantic 105 Eden Street Bar Harbor, Maine 04609 Dean of Institutional Advancement Lynn Boulger 207-801-5620, [email protected] Development Associate Amanda Ruzicka Mogridge 207-801-5625, [email protected] Development Officer Kristina Swanson 207-801-5621, [email protected] Alumni Relations/Development Coordinator Dianne Clendaniel 207-801-5624, [email protected] Manager of Donor Engagement Jennifer Hughes 207-801-5622, [email protected] Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in preparing all donor lists for this annual report. If a mistake has been made in your name, or if your name was omitted, we apologize. Please notify the development office at 207-801-5625 with any changes. www.coa.edu/support COA ANNUAL REPorT FY15: July 1, 2014–June 30, 2015 I love nothing more than telling stories of success and good news about our We love to highlight the achievements of our students, and one that stands out incredible college. One way I tell these stories is through a series I’ve created for from last year is the incredible academic recognition given to Ellie Oldach '15 our Board of Trustees called the College of the Atlantic Highlight Reel. A perusal of when she received a prestigious Fulbright Research Scholarship. It was the first the Reels from this year include the following elements: time in the history of the college that a student has won a Fulbright. Ellie is spending ten months on New Zealand’s South Island working to understand and COA received the 2014 Honor Award from Maine Preservation for our model coastal marsh and mussel bed communities.