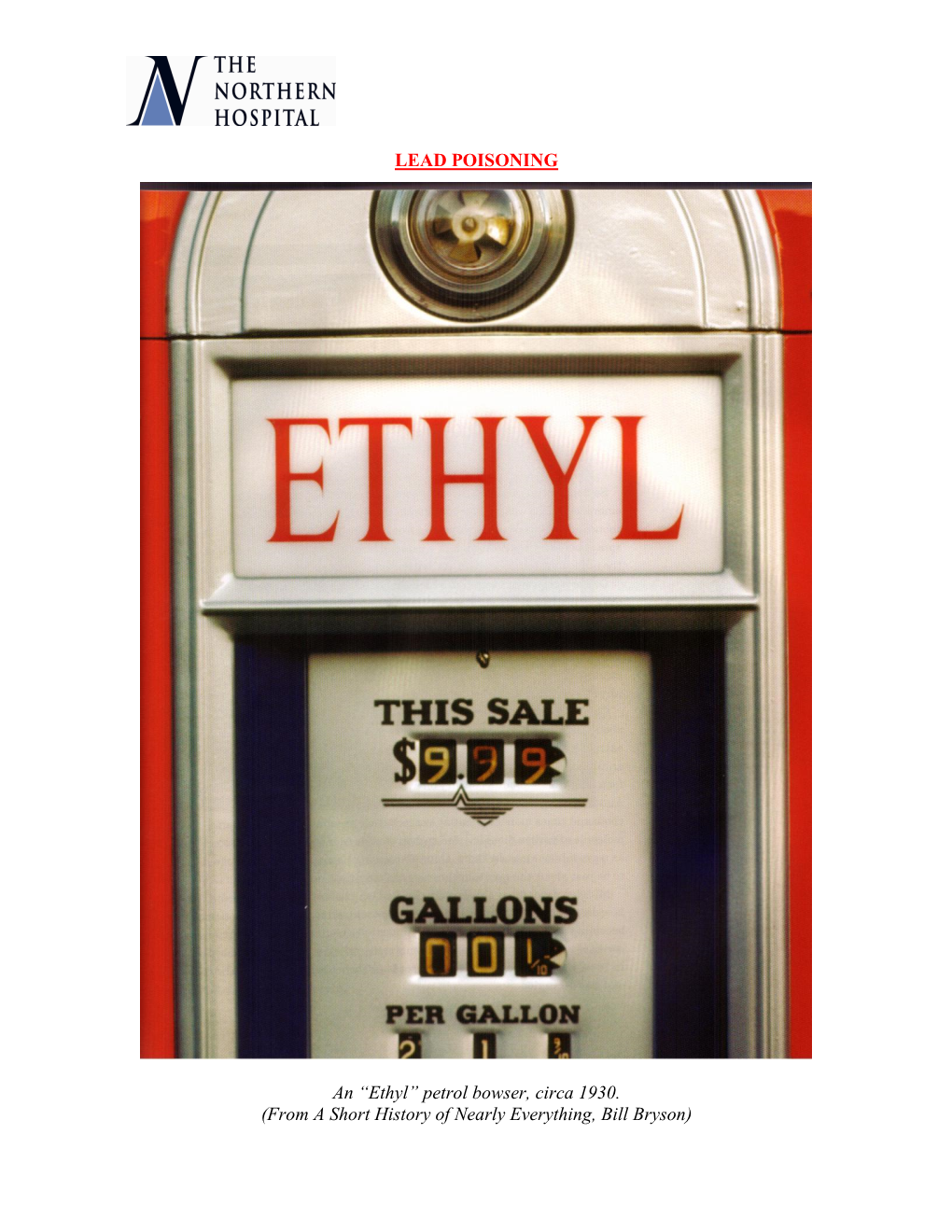

Lead Poisoning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Succimer for Treatment of Lead Poisoning

Review of Succimer for treatment of lead poisoning Glyn N Volans MD, BSc, FRCP. Department of Clinical Pharmacology, School of Medicine at Guy's, King's College & St Thomas' Hospitals, St Thomas' Hospital, London, UK Lakshman Karalliedde MB BS, DA, FRCA Consultant Medical Toxicologist, CHaPD (London), Health Protection Agency UK, Visiting Senior Lecturer, Division of Public Health Sciences, King's College Medical School, King's College , London Senior Research Collaborator, South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. Heather M Wiseman BSc MSc Medical Toxicology Information Services, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London SE1 9RT, UK. Contact details: Heather Wiseman Medical Toxicology Information Services Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust Mary Sheridan House Guy’s Hospital Great Maze Pond London SE1 9RT Tel 020 7188 7188 extn 51699 or 020 7188 0600 (admin office) Date 10th March 2010 succimer V 29 Nov 10.doc last saved: 29-Nov-10 11:30 Page 1 of 50 CONTENTS 1 Summary 2. Name of the focal point in WHO submitting or supporting the application 3. Name of the organization(s) consulted and/or supporting the application 4. International Nonproprietary Name (INN, generic name) of the medicine 5. Formulation proposed for inclusion 6. International availability 7. Whether listing is requested as an individual medicine or as an example of a therapeutic group 8. Public health relevance 8.1 Epidemiological information on burden of disease due to lead poisoning 8.2 Assessment of current use 8.2.1 Treatment of children with lead poisoning 8.2.2 Other indications 9. -

Sodium Cellulose Phosphate Sodium Edetate

Sevelamer/Sodium Edetate 1463 excreted by the kidneys. It may be used as a diagnostic is not less than 9.5% and not more than 13.0%, all calculated on supplement should not be given simultaneously with test for lead poisoning but measurement of blood-lead the dried basis. The calcium binding capacity, calculated on the sodium cellulose phosphate. dried basis, is not less than 1.8 mmol per g. concentrations is generally preferred. Sodium cellulose phosphate has also been used for the Sodium calcium edetate is also a chelator of other Adverse Effects and Precautions investigation of calcium absorption. heavy-metal polyvalent ions, including chromium. A Diarrhoea and other gastrointestinal disturbances have Preparations cream containing sodium calcium edetate 10% has been reported. USP 31: Cellulose Sodium Phosphate for Oral Suspension. been used in the treatment of chrome ulcers and skin Sodium cellulose phosphate should not be given to pa- Proprietary Preparations (details are given in Part 3) sensitivity reactions due to contact with heavy metals. tients with primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, Spain: Anacalcit; USA: Calcibind. Sodium calcium edetate is also used as a pharmaceuti- hypomagnesaemia, hypocalcaemia, bone disease, or cal excipient and as a food additive. enteric hyperoxaluria. It should be used cautiously in pregnant women and children, since they have high Sodium Edetate In the treatment of lead poisoning, sodium calcium calcium requirements. Sodu edetynian. edetate may be given by intramuscular injection or by Patients should be monitored for electrolyte distur- intravenous infusion. The intramuscular route may be Эдетат Натрия bances. Uptake of sodium and phosphate may increase CAS — 17421-79-3 (monosodium edetate). -

Uses and Administration Adverse Effects and Precautions Pharmacokinetics Uses and Administration

1549 The adverse effects of dicobalt edetate are more severe in year-old child: case report and review of literature. Z Kardiol 2005; 94: References. 817-2 3. the absence of cyanide. Therefore, dicobalt edetate should I. Schaumann W, et a!. Kinetics of the Fab fragments of digoxin antibodies and of bound digoxin in patients with severe digoxin intoxication. Eur 1 not be given unless cyanide poisoning is confirmed and 30: Administration in renal impairment. In renal impairment, Clin Pharmacol 1986; 527-33. poisoning is severe such as when consciousness is impaired. 2. Ujhelyi MR, Robert S. Pharmacokinetic aspects of digoxin-specific Fab elimination of antibody-bound digoxin or digitoxin is therapy in the management of digitalis toxicity. Clin Pharmacokinet 1995; Oedema. A patient with cyanide toxicity developed delayed1·3 and antibody fragments can be detected in the 28: 483-93. plasma for 2 to 3 weeks after treatment.1 The rebound in 3. Renard C, et al. Pharmacokinetics of dig,'><i<1-sp,eei1ie Fab: effects of severe facial and pulmonary oedema after treatment with decreased renal function and age. 1997; 44: 135-8. dicobalt edetate.1 It has been suggested that when dicobalt free-digoxin concentrations that has been reported after edetate is used, facilities for intubation and resuscitation treatment with digoxin-specific antibody fragments (see P (Jrations should be immediately available. Poisoning, below), occurred much later in patients with r.�p renal impairment than in those with normal renal func Proprietary Preparations (details are given in Volume B) 1. Dodds C, McKnight C. Cyanide toxicity after immersion and the hazards tion. -

An Oral Treatment for Lead Toxicity Paul S

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.67.783.63 on 1 January 1991. Downloaded from Postgrad MedJ (1991) 67, 63 - 65 D The Fellowship ofPostgraduate Medicine, 1991 Clinical Toxicology An oral treatment for lead toxicity Paul S. Thomas' and Charles Ashton2 'Northwick Park Hospital, Harrow, Middlesex HA] 3UJand2National Poisons Unit, Guy's Hospital, London SE], UK. Summary: Chronic lead poisoning has traditionally been treated by parenteral agents. We present a case where a comparison of ethylene diaminetetra-acetic acid was made with 2,3-dimethyl succinic acid (DMSA) which has the advantage oforal administration associated with little toxicity and appeared to be at least as efficacious. Introduction For many years the treatment of heavy metal ferase 112IU/I (normal<40). His electrolytes, poisoning has relied upon parenteral agents which urea, creatinine, clotting screening chest radio- themselves have a number of toxic side effects. We graph, computed tomographic head scan and lum- report a case ofplumbism which shows the benefits bar puncture were all normal. of using 2,3-dimethyl succinic acid (DMSA), a Re-evaluation revealed lead lines on his gingival treatment relatively new to Western countries. In margins and a urinary porphyrin screen was posi- by copyright. our case it was used in direct comparison to the tive indicating lead toxicity. Despite careful social, sodium-calcium salt of ethylene diaminetetra- occupational, and recreational history no cause for acetic acid, which has been the best available his excess lead intake could be found. As he was treatment. domiciled in India it was not possible to visit his home or workplace where he sold sarees. -

Antidotes Atropine Calcium

Version 2.9 Antidotes 4/10/2013 Atropine Indications AV conduction impairment: Cardiac glycosides , β-blockers , calcium channel blockers (CCBs) . Anticholinesterase inhibitors/Cholinergics: Organophosphates, carbamates Contraindications Relative: closed angle glaucoma, GIT obstruction, urinary obstruction Mechanism Competitive antagonist for ACh at muscarinic receptors. Pharmacokinetics Poor oral bioavailability, liver met, T ½=2-4hrs. Crosses BBB & placenta. 50% excreted unaltered. Administration AV conduction impairment: 0.6mg (20mcg/kg) IV repeated up to 3x Cholinergics: 1.2mg IV bolus, double dose q5mins until chest clear [also sBP>80mmHg, HR>80, dry axillae & no miosis]. Then infusion starting at ~10-20% of total loading dose (max 35mg/hr) Adverse Reactions Excessive dosage → Anticholinergic toxidrome. Calcium Indications CCB OD, HF exposure, hypocalcaemia, hyperkalaemia, iatrogenic hypermagnesaemia Contraindications Hypercalcaemia, ?digoxin toxicity - (contrary to traditional teaching, recently some evidence 2+ that Ca is not CI if on digoxin or even if digoxin toxic – however digoxin immune Fab & MgSO 4 10mmol might be preferred initially in the latter case) Mechanisms Restore low Ca2 + levels, binds F- ions, antagonises effects of high K + & Mg 2+ on heart. Administration Cardiac monitoring mandatory. CCBs: 20ml CaCl 2 IV (central line) or 60ml (1ml/kg) Ca gluconate IV (peripheral) over 5-10mins HF on skin: 2.5% Ca gel TOP OR local inj of 10% calcium gluconate (not fingers) OR Bier’s block with 2% Ca gluconate (i.e. 10ml of 10% in 40ml NS) for 20mins & release cuff OR same dose intra-arterially over 4 hrs & rpt prn. HF inhaled: Nebulised 2.5% Ca gluconate solution. HypoCa/HypoMg/HyperK: 5-10ml CaCl 2 or 10-20ml (1ml/kg) Ca gluconate IV over 5-10mins Adverse Reactions Transient hyperCa., vasodilatation, hypoBP, dysrhythmias, tissue damage from extravasated CaCl 2. -

Picture As Pdf Download

NOTABLE CASES Succimer therapy for congenital lead poisoning from maternal petrol sniffing An infant, born at 35 weeks’ gestation to a woman who sniffed petrol, had a cord blood lead level eight times the accepted limit. Treatment with oral dimercaptosuccinic acid promptly reduced his blood lead levels. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of congenital lead poisoning secondary to maternal petrol sniffing. We suggest that at-risk pregnancies should be identified, cord blood lead levels tested, and chelation therapy and developmental follow-up offered to affected infants. (MJA 2006; 184: 84-85) Clinical record therapy is recommended for any child with blood lead levels of μ 3 A 27-year-old Indigenous woman, who had sniffed petrol since 2.16 mol/L and over. Although chelation therapy in early child- childhood, presented for antenatal care during her first pregnancy. hood lowers blood levels, recent studies have not shown signifi- At the age of 14 years, she had severe lead encephalopathy that led cant improvement in cognitive and behavioural measurements 3,4,7 to chronic neurological deficits, including permanent ataxia and compared with untreated children. memory impairment. Her serum lead levels at 8 and 35 weeks’ There are a few case reports of neonatal lead intoxication that gestation were raised at 1.48 and 2.21 μmol/L, respectively (recom- occurred from maternal exposure to lead through pica, home 8-10 mended level, р 0.48 μmol/L1). renovation, or use of contaminated herbal medications. Petrol At 35 weeks’ gestation, she went into spontaneous labour and sniffing is a form of substance misuse that is widespread in some gave birth vaginally to a boy. -

Oral Chelation Therapy for Patients with Lead Poisoning

ORAL CHELATION THERAPY FOR PATIENTS WITH LEAD POISONING Jennifer A. Lowry, MD Division of Clinical Pharmacology and Medical Toxicology The Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics Kansas City, MO 64108 Tel: (816) 234-3059 Fax: (816) 855-1958 December 2010 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Background of Lead Poisoning …………………………………………………………...3 a. Clinical Significance of Lead Measurements …………………………………….3 b. Absorption of Lead and Its Internal Distribution Within the Body ………………3 c. Toxic Effects of Exposure to Lead in Children and Adults ………………………4 d. Reproductive and Developmental Effects………………………………………...5 e. Mechanisms of Lead Toxicity ……………………………………………………6 f. Concentration of Lead in Blood Deemed Safe for Children/Adults………………6 g. Use of Blood Lead Measurements as a Marker of Lead Exposure ……………….7 2. Management of the Child with Elevated Blood Lead Concentrations …………………...8 a. Decreasing Exposure……………………………………………………………...8 b. Chelation Therapy…………………………………………………………………8 3. Oral Chelation Therapy …………………………………………………………………...8 a. Meso-2,3 dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA, Succimer) …………………………8 i. Pharmacokinetics………………………………………………………….9 ii. Dosing …………………………………………………………………….9 iii. Efficacy……………………………………………………………………9 iv. Safety…………………………………………………………………….11 b. Racemic-2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS, Unithiol)……………11 i. Pharmacokinetics………………………………………………………...12 ii. Dosing ……………………………………………………………………12 iii. Efficacy…………………………………………………………………..12 iv. Safety…………………………………………………………………….12 c. Penicillamine……………………………………………………………………..12 i. Pharmacokinetics………………………………………………………...13 -

Other Data Relevant to an Evaluation of Carcinogenicity and Its Mechanisms

P 201-252 DEF.qxp 09/08/2006 11:36 Page 249 INORGANIC AND ORGANIC LEAD COMPOUNDS 249 4. Other Data Relevant to an Evaluation of Carcinogenicity and its Mechanisms 4.1 Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion 4.1.1 Inorganic lead compounds (a) Humans (i) Absorption Absorption of lead is influenced by the route of exposure, the physicochemical charac- teristics of the lead and the exposure medium, and the age and physiological status of the exposed individual (e.g. fasting, concentration of nutritional elements such as calcium, and iron status). Inorganic lead can be absorbed by inhalation of fine particles, by ingestion and, to a much lesser extent, transdermally. Inhalation exposure Smaller lead particles (< 1 µm) have been shown to have greater deposition and absorption rates in the lungs than larger particles (Hodgkins et al., 1991; ATSDR, 1999). In adult men, approximately 30–50% of lead in inhaled air is deposited in the respiratory tract, depending on the size of the particles and the ventilation rate of the individual. The proportion of lead deposited is independent of the absolute lead burden in the air. The half- life for retention of lead in the lungs is about 15 h (Chamberlain et al., 1978; Morrow et al., 1980). Once deposited in the lower respiratory tract, particulate lead is almost completely absorbed, and different chemical forms of inorganic lead seem to be absorbed equally (Morrow et al., 1980; US EPA, 1986). In two separate experiments, male adult volunteers were exposed to aerosols of lead oxide (prepared by bubbling propane through a solution of tetraethyl lead in dodecane and burning of resulting vapour) containing 3.2 µg/m3 lead (15 subjects) or 10.9 µg/m3 lead (18 subjects) in a room for 23 h/day for up to 18 weeks (Griffin et al., 1975a). -

The Selection and Use of Essential Medicines

This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the World Health Organization WHO Technical Report Series 933 THE SELECTION AND USE OF ESSENTIAL MEDICINES Report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2005 (including the 14th Model List of Essential Medicines) World Health Organization Geneva 2006 i WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data WHO Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines (14th : 2005: Geneva, Switzerland) The selection and use of essential medicines : report of the WHO Expert Committee, 2005 : (including the 14th model list of essential medicines). (WHO technical report series ; 933) 1.Essential drugs — standards 2.Formularies — standards 3.Drug information services — organization and administration 4.Drug utilization 5. Pharmaceutical preparations — classification 6.Guidelines I.Title II.Title: 14th model list of essential medicines III.Series. ISBN 92 4 120933 X (LC/NLM classification: QV 55) ISSN 0512-3054 © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publica- tions — whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution — should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Ed 092 563 Title Institution Report No Pub Date Note Available from Edrs Price Descriptors Identifiers Document Resume- Sp 008 1

DOCUMENT RESUME- ED 092 563 SP 008 167 TITLE Poisoning and Intoxication by Trace Elements in Children. At Abstract Review of the Worldwide Medical. Literature 1966-1971. INSTITUTION Public Health Service (DREW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Community Environmental Management. REPORT NO DREW-HSM-73-10005 PUB DATE 73 NOTE 104p. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (No price quoted) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Abstracts; Accidents; *Annotated Bibliographies; Clinical Diagnosis; *Health; Lead Poisoning; *Medical Case Histories; *Physiology; Safety IDENTIFIERS *Poisons ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography of 247 entries is divided into the following categories:(a) general aspects and reviews; (b) sources of poisoning, epideE-,..ology, and pica studies; (c) clinico-pathological studies;(d) diagnosis and screening; (e) laboratory methods; and (f) treatment and prevention. A subject and author index is included. (PD) ca° POISONING AND INTOXICATION BY TRACE ELEMENTS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. IN CHILDREN EDUCATICN IL WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS SEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN- ATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE. SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. an abstract review of the worldwide medical literature 1966-1971 DHEW Publication No. (HSM) 73-10005 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE Public Health Service Health Services and Mental Health Administration Bureau of Community Environmental Management Division of Community injury Control For sale by the Superintendent ae Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. -

EDTA Chelation Therapy in the Treatment of Toxic Metals Exposure

Original Article Spatula DD. 2011; 1(2):81-89 EDTA chelation therapy in the treatment of toxic metals exposure Toksik metallere maruz kalım tedavisinde EDTA şelasyon terapisi Nina Mikirova1, Joseph Casciari1, Ronald Hunninghake1, Neil Riordan1,2 1Riordan Clinic, Wichita, Kansas, USA. 2Medistem Inc, San Diego, California, USA SUMMARY BACKGROUND: Metal induced toxicity with wide range of physiological, biochemical and behavioral dysfunctions was reported in many studies. The chelation has been used for treatment to toxic metals’ exposure for many years. In our current clinical study, we compared different chelation protocols and two forms of EDTA (sodium calcium edetate and sodium edetate) in treatments of toxic metal exposure. METHODS: A 24 h urine samples were collected from each subject before and after treatment by Ca-EDTA or Na-EDTA. The levels of toxic and essential metals were measured by Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (AAS) with graphite furnace and by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer (ICP-AES). The cellular levels of ATP were determined by ATP-bioluminescence assay. Mitochondrial potential was measured by fluorometer and flow-cytometer after cells’ staining by mitochondrial dye. RESULTS: Data from over 600 patients with a variety of complaints, but not acute toxic mineral exposure, given chelation therapy with sodium EDTA or calcium EDTA, were analyzed. Ca-EDTA and Na-EDTA at intravenous infusions of 3 g per treatment were equally effective in removing lead from the body, while Ca-EDTA was more effective in aluminum removal. The removal of lead was dose dependent but non-linear. Chelation by different doses of Na-EDTA (3 g and 1 g) resulted in mean difference in lead urine less than 50%. -

4-Dimethylaminophenol Hydrochloride__第38版.Pdf

1550 Chelators Antidotes and started first since sodium calcium edetate may cause distributed but is concentrated in the kidney, liver, and Profile mobilisation of stored lead in symptomatic toxicity. A small intestine. Dimercaprol is rapidly metabolised and the suggested regimen is to give dimercaprol intramuscularly in metabolites and dimercaprol-metal chelates are excreted in Ditiocarb sodium is a chelator that has been used in nickel an initial dose of 4 mg/kg, followed at 4-hourly intervals by the urine and bile. Elimination is essentially complete carbonyl poisoning. Disulfiram (p. 2495.3), which is rapidly dimercaprol 3 to 4mg/kg intramuscularly and sodium within 4 hours of a single dose. metabolised to ditiocarb, has been used as an alternative. calcium edetate; the sodium calcium edetate may be given Ditiocarb has also been used in the destruction of cisplatin either intravenously, or intramuscularly at a different site Preparations wastes (see Handling and Disposal. p. 768.2). from the dimercaprol. Treatment may be continued for 2 to .......................... 7 days depending on the clinical response; in patients with Proprietary Preparations (details are given in Volume B) lead encephalopathy, combined therapy should be Edetic Acid (BAN, fiNN) Single-ingredient Preparations. Rus.: Zorex (30peKC). continued until the patient is stable. In severe lead Acide. Ed~tiqLie:AcidoedeticoiAcido. etilendiarni!'lotetraa poisoning, a minimum of 2 days without treatment should Mulfi·ingredient Preparatio·ns. Ukr.: Zarex (30peKc). cetieo; •• Acido .. Etilefldiafl'\minqtetraac:etico;Acidum. Edeti elapse before a second course of therapy with either C1.jm; Edathamil;Edetico; aCido;EdetHniha,ppo;. Edetinsaure; combined dimercaprol and sodium calcium edetate or Pharmacopoeial Preparations sodium calcium edetate alone is considered.