Italian Bookshelf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maurizio Basili Ultimissimo

Le tesi Portaparole © Portaparole 00178 Roma Via Tropea, 35 Tel 06 90286666 www.portaparole.it [email protected] isbn 978-88-97539-32-2 1a edizione gennaio 2014 Stampa Ebod / Milano 2 Maurizio Basili La Letteratura Svizzera dal 1945 ai giorni nostri 3 Ringrazio la Professoressa Elisabetta Sibilio per aver sempre seguito e incoraggiato la mia ricerca, per i consigli e le osservazioni indispensabili alla stesura del presente lavoro. Ringrazio Anna Fattori per la gratificante stima accordatami e per il costante sostegno intellettuale e morale senza il quale non sarei mai riuscito a portare a termine questo mio lavoro. Ringrazio Rosella Tinaburri, Micaela Latini e gli altri studiosi per tutti i consigli su aspetti particolari della ricerca. Ringrazio infine tutti coloro che, pur non avendo a che fare direttamente con il libro, hanno attraversato la vita dell’autore infondendo coraggio. 4 INDICE CAPITOLO PRIMO SULL’ESISTENZA DI UNA LETTERATURA SVIZZERA 11 1.1 Contro una letteratura svizzera 13 1.2 Per una letteratura svizzera 23 1.3 Sull’esistenza di un “canone elvetico” 35 1.4 Quattro lingue, una nazione 45 1.4.1 Caratteristiche dello Schweizerdeutsch 46 1.4.2 Il francese parlato in Svizzera 50 1.4.3 L’italiano del Ticino e dei Grigioni 55 1.4.4 Il romancio: lingua o dialetto? 59 1.4.5 La traduzione all’interno della Svizzera 61 - La traduzione in Romandia 62 - La traduzione nella Svizzera tedesca 67 - Traduzione e Svizzera italiana 69 - Iniziative a favore della traduzione 71 CAPITOLO SECONDO IL RAPPORTO TRA PATRIA E INTELLETTUALI 77 2.1 Gli intellettuali e la madrepatria 79 2.2 La ristrettezza elvetica e le sue conseguenze 83 2.3 Personaggi in fuga: 2.3.1 L’interiorità 102 2.3.2 L’altrove 111 2.4 Scrittori all’estero: 2.4.1 Il viaggio a Roma 120 2.4.2 Parigi e gli intellettuali svizzeri 129 2.4.3 La Berlino degli elvetici 137 2.5 Letteratura di viaggio. -

SHOELESS JOE Di William Patrick Kinsella

Condividi 2 Altro Blog successivo» Crea blog Entra A.A.A.Book.Wanted Siamo sempre a caccia di libri... giovedì 24 febbraio 2011 Noi leggiamo con loro SHOELESS JOE di William Patrick Kinsella William Patrick Kinsella è un nome che probabilmente dice poco al lettore italiano e lo stesso vale per questo romanzo (in apparenza). Si, perché Shoeless Joe è il primo libro di W. P. Kinsella tradotto in italiano, eppure la storia è nota a ...i nostri ereader lettori e non. Ray vive con moglie e figlia in una fattoria in Iowa quando un giorno Seguici anche su Twitter una voce lo chiama a costruire un campo da baseball per far tornare a Segui @AAABookWanted giocare Sholess Joe Jackson, un campione del passato squalificato a vita perché coinvolto in uno scandalo. Ray segue la voce e Facebook costruisce il campo. Ma la voce torna a chiamare, questa volta vuole che Ray parta per un viaggio che lo porterà a trascinare A.A.A.Book.Wanted Blog fuori dal suo isolamento, con una specie di sgangherato rapimento fallito, J. D. Salinger, perché così deve essere, è Mi piace 80 necessario. Vi sembra una storia già sentita? Probabile, il libro è del 1982 e il film che ne è stato tratto è del 1989. Il titolo italiano è L’uomo dei sogni. Esatto! Il protagonista è Kevin Iscriviti a AAA.Book.Wanted Kostner. Il tema dominante del romanzo è il Post baseball, ma questo è insieme cornice e sfondo, perché è si un romanzo sul Commenti baseball ma è anche una favola, un romanzo che parla di sogni, è possibile dare vita ai sogni, farli letteralmente “vivere”? Share it Scritto in prima persona con linguaggio Share this on Facebook agile è un libro che scorre via velocemente appassionando. -

Rivista Trimestrale Di Cultura

CENOBIO rivista trimestrale di cultura anno LXVII numero ii aprile-giugno 2018 Fondatore Un fascicolo costa 16 chf / 15 euro. Pier Riccardo Frigeri (1918-2005) Condizioni di abbonamento per il 2018: Direttore responsabile svizzera (in chf) Pietro Montorfani ordinario 45 sostenitore 100 Comitato di redazione Federica Alziati italia (in euro) Daniele Bernardi ordinario 40 Andrea Bianchetti sostenitore 80 Comitato di consulenza altri paesi (in euro) Giuseppe Curonici ordinario 50 Maria Antonietta Grignani via aerea 80 Fleur Jaeggy sostenitore 100 Fabio Merlini Daniela Persico Versamenti dalla Svizzera Giancarlo Pontiggia ccp 69-2337-7 Manuel Rossello iban ch94 0900 0000 6900 2337 7 Claudio Scarpati Rivista Cenobio, 6933 Muzzano Redazione svizzera Versamenti dall’estero c/o Pietro Montorfani Gaggini Bizzozero sa - Muzzano-Piodella Via alle Cascine 32 ch 6933 conto corrente 103700-21-2 - Arbedo ch 6517 c/o Credit Suisse, ch-6900 Lugano iban ch83 0483 5010 3700 2100 2 Redazione italiana bic: creschzz69a c/o Federica Alziati Rif. Rivista Cenobio Via Liberazione 14 20083 Gaggiano (mi) Abbonamenti, fascicoli arretrati e volumi delle Edizioni Cenobio Amministrazione e stampa possono essere acquistati online Industria Grafica Gaggini-Bizzozerosa tramite il nostro webshop sul sito: ch-6933 Muzzano-Piodella www.edizionicenobio.com tel. 0041 91 935 75 75 Tutti i diritti riservati. È vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale, non autorizzata dall’editore. Questo fascicolo è stato pubblicato con il © Edizioni Cenobio Contributo del Cantone Ticino derivante dall’Aiuto federale Email: [email protected] per la salvaguardia e promozione della lingua e cultura italiana issn ooo8-896x SOMMARIO marco maggi 5 incontri Poeti per Giorgio Morandi fabio camponovo 27 Non ero iperattivo, ero svizzero. -

Lettere Di Ringraziamento in Risposta All'invio Di Pubblicazioni

Presidenza Carlo Azeglio CIAMPI Segreteria generale Lettere di ringraziamento in risposta all'invio di pubblicazioni Busta Segnatura Nominativo Data QUALIFICA Titoli pubblicazioni 95 AC12L Ruggi d'Aragona 1999 nov 24 - nov 29 Capo Servizio Movimenti fascicoli libri Affari Lucrezia Interni e Segreteria generale Risposte a firma del Presidente e del Consigliere direttore dell’Ufficio di Segreteria generale Pranzolone Livia 2001 lug 9 Il mito dell'Università "Gli studenti trentini e le origini dell'Università di Trento" di Graziano Riccadonna Traquandi Giuseppe 2001 feb 21 "Montecchio Vesponi" Libreria Colonnese 2000 ott 20 Catalogo di libri esauriti e rari Istituto di Studi e 2000 nov 12 Bollettino mensile agosto settembre Analisi economica e ottobre Associazione Auser Le 2000 feb 18 "Un villaggio chiamato Dien Bien Muse Phu" Banca Intesa 2000 dic 11 Relazione andamento gestione primo semestre 2000 Banca Nazionale 2000 feb 21 "Moneta e credito" rivista Lavoro trimestrale Enea 2000 mag 10 Informazione Internazionale n. 101 Banca d'Italia 1999 nov 02 Scheda storico - bibliografica Opera di Ridolfino Venuti "Veteris Latii antiquitatum amplissima collectio 1776 dalla Biblioteca Paolo Baffi Bisignani Giovanni 1999 ott 20 Amm. Del. SM Logistics SM Logistics: Sinergia e Qualità Gruppo Serra Merzario Komansky David H. 1999 ott 29 Capo Ufficio Esecutivo Merrill Internet / e Commerce Lynch Alunni IV classe 2000 gen 17 disegnato da Cecere Andrè Calendar Ciampi 2000 dell'Istituto Magistrale Francesco di Matera "Stigliani" Berlinguer Luigi 2000 gen 24 Ministro Pubblica Istruzione Rapporto "La scuola e la Comunicazione" Muarizio Mini 2000 mar 29 Direttore del Periodico periodico Associazione Lavoratori comunali "Il Caffè 96 AC12L 1 D'Andrea Antonio 1999 ott 25 - nov 18 Università di Brescia facoltà di "Verso l'incerto bipolarismo. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reappropriating Desires In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reappropriating Desires in Neoliberal Societies through KPop A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Asian American Studies By Daisy Kim 2012 © Copyright by Daisy Kim 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Reappropriating Desires in Neoliberal Societies through KPop By Daisy Kim Master of Arts in Asian American Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Victor Bascara, Chair ABSTRACT: This project analyzes contemporary KPop as a commercial cultural production and as a business model that emerged as the South Korean state’s U.S-aligned neoliberal project, and its functions as an ideological, political, and economic apparatus to effectively affect the production and reproduction of desires in the emergence of various sub-cultures at disparate sites across the globe. Legacies of colonialism, neocolonialism, and (late) capitalist developments that sanctioned the conditions for this particular form of mass and popular culture, KPop as a commercial commodity is also a contesting subject of appropriation and reappropriation by those in power and those in the margins. By examining the institutionalized and systematic new media platforms and internet technologies which enables new forms of globalized interactions with mass culture in general and KPop in particular, the thesis locates how resistant and alternative (sub) cultures emerge in variable conditions. Through newly found mediums online, emerging cultural formations challenge and negotiate the conditions of commercial and dominant systems, to allow various and localized subaltern (secondary) cultural identities to decenter, disrupt, and instigate KPop and its neoliberal governance, to reorient and reappropriate itself in the process as well. -

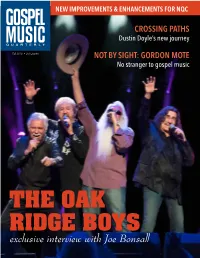

THE OAK RIDGE BOYS Exclusive Interview with Joe Bonsall “Therefore You Also Be Ready, for the Son of Man Is Coming at an Hour You Do Not Expect.” (NKJV)

NEW IMPROVEMENTS & ENHANCEMENTS FOR NQC CROSSING PATHS Dustin Doyle’s new journey Fall 2015 s 3rd Quarter NOT BY SIGHT: GORDON MOTE No stranger to gospel music THE OAK RIDGE BOYS exclusive interview with Joe Bonsall “Therefore you also be ready, for the Son of Man is coming at an hour you do not expect.” (NKJV) Fans have waited two years for a new recording from this talented family band, and THAT DAY IS COMING. Releasing just days before the ever-popular Singing News Fan Awards, where The Collingsworth Family has an unprecedented 5 nominations (including Artist of the Year), this highly anticipated recording will definitely be a “must-have” for all Southern Gospel enthusiasts. More importantly, it is their desire to remind all people that the day is soon coming when Jesus Christ will appear from the eastern sky to gather His children. Join Phil, Kim, Brooklyn, Phillip, Courtney & Olivia as they take you on a musical journey that celebrates the promises, faithfulness and awesome magnificence of a living God! FEATURING THE HIT SONG “WHAT THE BIBLE SAYS” AVAILABLE SEPTEMBER 25 AT RETAIL OUTLETS WORLDWIDE www.stowtownrecords.com www.thecollingsworthfamily.com BIRTHED FROM A DESIRE TO REKINDLE THE UNIQUE WORSHIP EXPERIENCE THAT ONLY COMES FROM CONGREGATIONAL HYMN SINGING... THE GOSPEL MUSIC HYMN SING BRINGS TOGETHER SOME OF YOUR FAVORITE GOSPEL ARTISTS, LIVE MUSICIANS, CHOIR, AND A MULTITUDE OF FELLOW BELIEVERS, UNITING THEIR VOICES FOR AN UNFORGETTABLE EVENING, SINGING YOUR ALL-TIME FAVORITE HYMNS AND CLASSIC GOSPEL SONGS. IT’S NOT A CONCERT... IT’S A WORSHIP EXPERIENCE... IT’S hosted by GERALD WOLFE THE GOSPEL MUSIC HYMN SING. -

Literature Music Cinema Letteratura Musica Cinema

In collaborazione con A+G Design Cultura Main partner Informazioni al pubblico Partner Teatro Dal Verme tel 02 87905 Provincia di Milano LETTERATURA MUSICA CINEMA tel 02 7740 6308 / 6326 OTTAVA EDIZIONE www.lamilanesiana.it Biglietteria TicketOne tel 02 8790 5201 www.ticketone.it Teatro Dal Verme via San Giovanni sul Muro 2 Teatro alla Scala piazza della Scala Rappresentanza a Milano Teatro degli Arcimboldi della Commissione europea e Ufficio a Milano viale dell’Innovazione 1 del Parlamento europeo Spazio Oberdan viale Vittorio Veneto 2 LITERATURE MUSIC CINEMA Sala Buzzati HOTEL EIGHTH EDITION Corriere della Sera PRINCIPE DI SAVOIA via Balzan 3 MILANO angolo via San Marco 21 Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia via San Vittore 21 Promosso da Provincia di Milano Ideato e diretto da Elisabetta Sgarbi LA MILANESIANA 2007 LETTERATURA MUSICA CINEMA I conflitti dell’Assoluto › Le sedi 2007 › Spazio Oberdan OTTAVA EDIZIONE › Teatro Dal Verme › Sala Buzzati / Corriere della Sera › Teatro alla Scala › Museo Nazionale della Scienza 14 1+1 24 giugno / 10 luglio 2007 › Teatro degli Arcimboldi › e della Tecnologia serate al serate al TEATRO DAL VERME TEATRO 13+1 1 degli ARCIMBOLDI oltre aperitivi con gli autori serata al 100 TEATRO ALLA SCALA 5 OSPITI INTERNAZIONALI alla Sala BUZZATI appuntamenti allo e al MUSEO NAZIONALE DELLA SPAZIO OBERDAN SCIENZA E DELLA TECNOLOGIA DOMENICA 24 GIUGNO MERCOLEDÌ 27 GIUGNO VENERDÌ 29 GIUGNO DOMENICA 1 LUGLIO Echos aus einem düesteren Sull’Assoluto Dipendenza assoluta 25 GIUGNO - 9 luglio ore 12.00 Reich (v. orig., 1990, 91’) di Günter Blobel (Premio di Elizabeth Gilbert Horror has gone L’Assoluto di Israele Elegia dell’Assoluto tra Play of Giants The Wild Blue Yonder Nobel per la medicina 1999) Concerto Michael Cunningham, Elie Wiesel, Letteratura Musica Arte Wole Soyinka, Edward P. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Edited by Andrew Colin Gow (Edmonton, Alberta) In cooperation with Sylvia Brown (Edmonton, Alberta) Falk Eisermann (Berlin) Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Heil (Heidelberg) Susan C. Karant-Nunn (Tucson, Arizona) Martin Kaufhold (Augsburg) Erik Kwakkel (Leiden) Jürgen Miethke (Heidelberg) Christopher Ocker (San Anselmo and Berkeley, California) Founding Editor Heiko A. Oberman † VOLUME 183 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/smrt Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Polemic and Dialogue in the Late Middle Ages Edited by Ian Christopher Levy Rita George-Tvrtković Donald F. Duclow LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www. knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover illustration: Opening leaf of ‘De pace fidei’ in Codex Cusanus 219, fol. 24v. (April–August 1464). Photo: Erich Gutberlet / © St. Nikolaus-Hospital/Cusanusstift, Bernkastel-Kues, Germany. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nicholas of Cusa and Islam : polemic and dialogue in the late Middle Ages / edited by Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtkovic, Donald F. -

LIBRI DA PREMIO Dal 1 Giugno Al 15 Luglio 2005

LIBRI DA PREMIO dal 1 giugno al 15 luglio 2005 Tra il folto panorama dei premi letterari italiani, una selezione delle opere vincitrici delle ultime edizioni. Premio Adei Wizo Opere di narrativa edita, di un autore vivente - MILANO Dolci le tue parole / Richler Nancy; Milano, Il Saggiatore, 2005 819.136/RIC La mia vita / Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Palermo: Sellerio, 2003 928.31/REI La donna che disse no / Aaron Soazig; Milano: Guanda, 2003 843.92/AAR Premio Alassio 100 libri - Un autore per l'Europa Narrativa italiana edita – ALASSIO N. / Ernesto Ferrero, Torino : Einaudi, 2000 853.91/FER Tempo perso / Bruno Arpaia; Parma : Guanda, 2002 853.91/ARP Quando Dio ballava il tango / Laura Pariani; Milano: Rizzoli, 2002 853.91/PAR La mennulara / Simonetta Agnello Hornby; Milano: Feltrinelli, 2002 853.91/AGN Una barca nel bosco / Paola Mastrocola; Parma : Guanda, 2004 853.91/MAS Premio Bagutta Opere edite di saggistica, narrativa e poesia pubblicate nell'anno in corso. MILANO Le poesie e prose scelte / Andrea Zanzotto ; a cura di Stefano Dal Bianco e Gian Mario Villalta ; con due saggi di Stefano Agosti e Fernando Bandini; Milano : A. Mondadori, 1999 858.91/ZAN La casa di ghiaccio : venti piccole storie russe / Serena Vitale; Milano: A. Mondadori, 2000 853.91/VIT La letteratura e gli dèi / Roberto Calasso; Milano: Adelphi, 2001 809/CAL Il collo dell'anitra / Orelli Giorgio ; Milano: Garzanti, 2001 851.91/ORE Premio Bancarella Narrativa e saggistica italiana e straniera pubblicata per la prima volta in Italia nell'anno solare antecedente al Premio PONTREMOLI Il ragno : thriller / Michael Connelly; Casale Monferrato: Piemme, 1999 813.5/CON La gita a Tindari / Andrea Camilleri; Palermo : Sellerio, 2000 853.91/CAM L'uomo che curava con i fiori / Audisio Di Somma Federico ; Casale Monferrato: Piemme, 2001 853.92/AUD Amiche di salvataggio / Appiano Alessandra ; Milano: Sperling Paperback, 2005 853.92/APP Il cavaliere e il professore. -

THE GOD-MAN the Life, Journeys and Work of Meher Baba with an Interpretation of His Silence and Spiritual Teaching

THE GOD-MAN The Life, Journeys and Work of Meher Baba with an Interpretation of his Silence and Spiritual Teaching Second Edition, second printing with corrections (2010) By C. B. Purdom Avatar Meher Baba Trust eBook June 2011 Copyright © 1964 C. B. Purdom Copyright © Meher Spiritual Centre, Inc. Source and short publication history: This eBook reproduces the second printing (2010) of the second edition of The God-Man: The Life, Journeys and Work of Meher Baba with an Interpretation of his Silence and Spiritual Teaching. This title was originally published by Allen and Unwin (London) in 1964; the second edition, first printing, was published by Sheriar Press (North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, 1971), and in its second printing, by Sheriar Foundation (Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, 2010). eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust’s eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non-facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust’s web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba’s lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. They have been created through a process of scanning the original pages, running these scans through optical character recognition (OCR) software, reflowing the new text, and proofreading it. Except in rare cases where we specify otherwise, the texts that you will find here correspond, page for page, with those of the original publications: in other words, page citations reliably correspond to those of the source books. -

Fogli» N° 24 (2003)

N. 24 Aprile 2003 FOGLI Informazioni dell’Associazione Biblioteca Salita dei Frati - Lugano SOMMARIO PRESENTAZIONE pag. 2 DOCUMENTI Il contributo di padre Giovanni Pozzi alla Biblioteca Salita dei Frati di Fabio Soldini pag. 3 L’archivio di padre Giovanni Pozzi di Riccardo Quadri pag. 13 Rilettura del Magnificat (Luca 1, 46-55) di Giovanni Raboni pag. 17 Appunti sulla Biblioteca cantonale di Lugano in appendice a una storia culturale del Liceo di Giancarlo Reggi pag. 19 RARA ET CURIOSA Fantasmi cattolici. Un manoscritto sulle presunte manifestazioni spiritiche di Cabbio (1904) di Aldo Abächerli pag. 25 IN BIBLIOTECA La Biblioteca Salita dei Frati e il catalogo collettivo del Sistema bibliotecario ticinese di Luciana Pedroia pag. 38 L’attività espositivia 2002-2003 di Alessandro Soldini pag. 39 Pubblicazioni entrate in biblioteca nel 2002 pag. 42 CRONACA SOCIALE Verbale dell’Assemblea del 29 aprile 2002 pag. 64 Convocazione dell’Assemblea del 29 aprile 2003 pag. 67 Relazione del Comitato sull’attività svolta nell’anno sociale 2002-2003 e programma futuro pag. 68 Conti consuntivi 2002 e preventivi 2003 pag. 74 Contributi pubblicati su “Fogli” 1-23 (1981-2002) pag. 76 Pubblicazioni curate dall’Associazione Biblioteca Salita dei Frati pag. 77 www.fogli.ch Presentazione Questo ventiquattresimo numero di Fogli si apre con due testi intesi a documentare l'attività di padre Giovanni Pozzi, scomparso alla fine di luglio del 2002. Il primo, per la penna di Fabio Soldini, ricostruisce il suo fondamentale contributo alla Bi- blioteca Salita dei Frati dalla sua escogitazione e poi dalla sua apertura: un capitolo certamente significativo delle vicende culturali di questo paese, fatto da una parte di incontri pubblici in una sede istituzionale ormai consolidata, dall'altra delle pubbli- cazioni che ne accrescono di anno in anno il patrimonio bibliografico. -

Catalogo 2006

2006catalogo-cop 30-11-2006 9:47 Pagina 2 EDIZIONI CADMO Catalogo 2006 Edizioni Cadmo Via Benedetto da Maiano,3 50014 Fiesole FI tel. 055-50181 fax 055-5018201 [email protected] www.cadmo.com *2006catalogo 30-11-2006 9:45 Pagina 1 EDIZIONI CADMO Catalogo 2006 *2006catalogo 30-11-2006 9:45 Pagina 2 Il presente catalogo è consultabile su internet al seguente indirizzo www.cadmo.com Distribuzione per l’Italia: Distribuzione: Via Forlanini, 36 Loc. Osmannoro 50019 Sesto Fiorentino (FI) Tel.: +39 055 30 13 71 Fax: +39 051 35 27 04 Promozione: Via Zago, 212 40128 Bologna Tel.: +39 051 35 27 04 Distribuzione per l’estero Via Benedetto da Maiano, 3 50014 Fiesole (FI) Tel.: +39 055 50 18 1 Fax: +39 055 50 18 201 [email protected] www.casalini.it Per le opere disponibili presso l’editore rivolgersi direttamente a: Edizioni Cadmo Via Benedetto da Maiano,3 50014 Fiesole FI tel. 055-50181 fax 055-5018201 [email protected] www.cadmo.com Distribuzione on-line: http://digital.casalini.it http://eio.casalini.it Cadmo s.r.l. – Cap. soc. € 52.000,00 – reg. Trib. FI 59757 – C.C.I.A.A. Firenze 438147 N. Id. C.E.E. e P. IVA 04312990486 – C.C.P. 29486503 Sede legale: C.so de’ Tintori, 8 – 50122 Firenze *2006catalogo 30-11-2006 9:45 Pagina 3 PRESENTAZIONE Cadmo è nata a Roma nel 1975. Era una casa editrice che si occupava soprattutto di filosofia. Nel 1991 fu portata a Fiesole, da Mario Casalini che la fece diventare uno spazio per le discipline umanistiche affronta- te da studiosi di differenti nazionalità.