DO IT YOURSELF Moreover, the Materials Were Easy to Obtain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIT 4.567 Introduction to Computation in Architectural Design Spring

MIT 4.567 Introduction to Computation in Architectural Design Spring 2017 Takehiko Nagakura Legend A modest modeling B some difficult portions in modeling C challenging Ref Do not select (For reference only) Architects Buildings Year Built Reference Notes Andrea Palladio B 1 Palazzo Da Porto 1552 built Palladio Pl.37-40 (Palazzo Iseppo Da Porto) Forssman Scamozzi Vol.1. p49 B 2 Villa Almerico 1569 built Palladio Pl.52-55 (Villa Rotonda) Scamozzi Vol.2. p8 Camillo B 3 Villa Zen 1566 built Palladio Pl.104-107 partiall involvement (Villa Zeno) Scamozzi Vol.3. p37 by Palladio B 4 Villa Foscari 1560 built Palladio Pl.108-110 (La Malcontenta) Scamozzi Vol.3. p8 B 5 Villa Pisani-Placco 1555 built Palladio Pl.114-117 Scamozzi Vol.2. p20 B 6 Villa Saraceno Lombardi 1548 built Palladio Pl.128-130 B 7 Villa Godi 1552 built Palladio Pl.153-155 Hofer Scamozzi Vo.2. p27 B 8 Villa Sarego Boccoli 1569 built Palladio Pl.156-159 (a.k.a. Villa Serego) Scamozzi Vol.3. p48 C 9 Invenzione per una unknown unbuilt Palladio Pl.168-170 irregular site situazione in Venezia Scamozzi Vol.4. p53 B 10 Villa Pietro Caldogno 1570 built Palladio Pl.196-198 painting on wall Scamozzi Vol.2. p67 B 11 Villa Mocenigo(Badoer) 1563 built Scamozzi Vol.3. p51 Puppi B 12 Villa Emo 1567 built Scamozzi Vol.3. p24 Lewis Ref Villa Marcello Ref Villa Fratelli Bissaro Architects Buildings Year Built Reference Notes Le Corbusier B 1 Maison de Errazuris Au Chili 1930 unsure Boesiger Vol.2 p49 RC + wood A 2 Villa de Mandrot 1931 built Boesiger Vol.2 p59 A 3 Durand Alger 1933 unbuilt Boesiger -

Neil Levine's the Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright

The Avery Review Joseph M. Watson – The Antinomies of Usonia: Neil Levine’s The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright In 1925 Frank Lloyd Wright introduced a neologism to readers of the Dutch Citation: Joseph M. Watson, “The Antinomies of Usonia: Neil Levine’s The Urbanism of Frank journal Wendingen. This new term—Usonian—would soon become synony- Lloyd Wright,’” in the Avery Review 25 (September mous with Wright’s late-career architecture and the socio-spatial regime he 2017), http://www.averyreview.com/issues/25/the- antinomies-of-usonia. envisioned to encompass those works. He casually inserted his coinage into an essay titled “In the Cause of Architecture: The Third Dimension,” which revisited the thesis of his 1901 “The Art and Craft of the Machine” to argue that if the Machine (always, for Wright, with a capital M) could be properly domesticated, it would become a means for overcoming the dehumanizing tendencies of industrialism and the stultifying effects of stylistic revivalism. After characterizing the Renaissance as a misguided project akin to aesthetic miscegenation—“a mongrel admixture of all the styles of the world”—Wright offered a prediction: “Here in the United States may be seen the final Usonian degradation of that ideal—ripening by means of the Machine for destruction by the Machine.” [1] Without explicitly defining his novel modifier, Wright [1] Frank Lloyd Wright, “In the Cause of Architecture: The Third Dimension” (1925), in Bruce Brooks nevertheless elliptically clarified Usonian’s signification. If American artists and Pfeiffer, ed., Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, architects eschewed their misguided fascination with “European backwash,” vol. -

Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J

Architecture Publications Architecture Winter 2008 Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J. Naegele Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/54. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Abstract Why "Wright in Iowa?" Are there ways that Wright's Iowa works are distinguished from his built works elsewhere? Iowa is a typical Midwest state, exceptional in neither general geography nor landscape. The ts ate's urban areas are minor, and Iowa has never been known for its subscription to avant-garde architecture. Its most renowned artist, Grant Wood, painted Iowa's rolling hills and pie-faced people in cartoon-like images that simultaneously champion and question the coalescence of people and place. Indeed, the state's most convincing buildings are found on its farms with their unpretentious, vernacular, agricultural buildings. Disciplines Architectural History and Criticism Comments This article is from Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly 19 (2008): 4–9. Posted with permission. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs/54 a (Photos above and opposite page, top right) The Lowell and Agnes Walter hy "Wright in Iowa?" Are House, "Cedar Rock," Quasqueton, W there ways that Wright's Iowa. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 \M/IVIUJ i ^vy. (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________________ historic name Wayfarers Chapel ________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location ___________________________ street & number 5755 Palos Verdes Drive South_______ NA d not for publication city or town Rancho Palos Verdes________________ NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Los Angeles. code 037_ zip code 90275 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this C3 nomination D request f fr*d; (termination -

Preserving the Textile Block at Florida Southern College a Report Prepared for the World Monuments Fund Jeffrey M

Preserving the Textile Block at Florida Southern College A Report Prepared for the World Monuments Fund Jeffrey M. Chusid, Preservation Architect 18 September 2009 ISBN-10: 1-890879-43-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-890879-43-3 © 2011 World Monuments Fund 2 Letter from World Monuments Fund President Bonnie Burnham 4 Letter from Florida Southern President Anne B. Kerr, Ph.D. 5 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 7 Preservation Philosophy 7 History and Significance 10 Ideas behind the System 10 Description of the System 10 Conservation Issues with the System in Earlier Sites 13 Recent Conservation Projects at the Storer, Freeman, and Ennis Houses 14 Florida Southern College 16 A History of Changes 18 Site Conditions and Analysis 19 Contents Prior research and observations 19 WMF Site visit 19 Taxonomy of Conservation Problems in the Textile-Block System 20 Issues and Challenges 22 The Textile-Block System 22 The Block 23 Methodologies 24 Conservation 25 Recommendations 26 Appendix A: Visual Conditions Documentation 29 Appendix B: Team Members 38 3 In April 2009, World Monuments Fund was honored to convene a historic gathering of historians, architects, conservators, craftsmen, and scientists at Florida Southern College to explore Frank Lloyd Wright’s use of ornamental concrete textile block construction. To Wright, this material was a highly expressive, decorative, and practical approach to create monumental yet affordable buildings. Indeed, some of his most iconic structures, including the Ennis House in Los Angeles, utilized the textile block system. However, like so many of Wright’s experiments with materials and engineering, textile block has posed major challenges to generations of building owners, architects, and conservators who have struggled with the system’s material and structural performance. -

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Through 1989” Photocopied articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: from 1956-1989, bulk 1989 Binder 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1990” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Date: 1990 Binder 3—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1991” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: 1991-1992, bulk 1991 Box 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Deaccession? Files” Folder: Sotheby’s catalogue—Gagliano violin and sales slip Folder: Slides, photos, receipts, correspondence, appraisal for Gagliano violin and bow. o Date: 1989 Box 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Vintage Publications on the Zimmerman House” “The Zimmerman House Historic Structure Report” (2 copies); also includes a press release (not attached) o Date: 1989 “A Classic Usonian: Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1950 House for Isadore J. and Lucille Zimmerman.” General information, labels. o Date: 1990 Folder: “Exhibition: A Classic Usonian: Label Copy.” Also an unattached article; label copy from exhibit appears to be the same as previous item. “Currier Grant Application for National Endowment for the Humanities for Training Zimmerman House Guides.” Also includes unattached correspondence, a docent bulletin, a memorandum, and a priorities evaluation. o Dates: 1990-1991, bulk 1990 Box 3—Labeled “Uncatalogued Materials” Newsclipping about Dr. Zimmerman o Date: undated 2 color photos of exterior of Zimmerman House with inscriptions from Zimmermans on back o Date: 1976 Black and white photo of exterior of Zimmerman House in winter o Date: undated 3 B & W photos of Lucille Zimmerman’s family o Date: undated Postcard with picture of S.C. -

Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia: preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia: preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19369. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Frank Lloyd Wright's

Usonia, N E W Y O R K PROOF 1 Usonia, N E W Y O R K Building a Community with Frank Lloyd Wright ROLAND REISLEY with John Timpane Foreword by MARTIN FILLER PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS, NEW YORK PROOF 2 PUBLISHED BY This publication was supported in part with PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS funds from the New York State Council on the 37 EAST SEVENTH STREET Arts, a state agency. NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 Special thanks to: Nettie Aljian, Ann Alter, Amanda For a free catalog of books, call 1.8... Atkins, Janet Behning, Jan Cigliano, Jane Garvie, Judith Visit our web site at www.papress.com. Koppenberg, Mark Lamster, Nancy Eklund Later, Brian McDonald, Anne Nitschke, Evan Schoninger, © Princeton Architectural Press Lottchen Shivers, and Jennifer Thompson of Princeton All rights reserved Architectural Press—Kevin C. Lippert, publisher Printed in China First edition Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Reisley, Roland, – No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any Usonia, New York : building a community with manner without written permission from the publisher Frank Lloyd Wright / Roland Reisley with John except in the context of reviews. Timpane ; foreword by Martin Filler. p. cm. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify isbn --- owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected . Usonian houses—New York (State)—Pleasant- in subsequent editions. ville. Utopias—New York (State)—Pleasantville— History. Architecture, Domestic—New York All photographs © Roland Reisley unless otherwise (State)—Pleasantville. Wright, Frank Lloyd, indicated. –—Criticism and interpretation. i. Title: Usonia. ii. Timpane, John Philip. iii. -

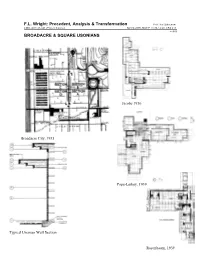

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright 978-2-86364-338-9 Cinq Approches ISBN / Approches Cinq

frank lloydwright DANIEL TREIBER DANIEL 978-2-86364-338-9 PARENTHÈSES ISBN cinq approches / approches cinq Wright, Lloyd Frank / Treiber Daniel www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com WRIGHT, JUSQU’À NOUS Dans ce nouveau livre que je consacre à Frank Lloyd Wright, je me propose d’aborder son œuvre selon cinq approches différentes. 978-2-86364-338-9 L’essai introductif est une présentation de ensemble de ses travaux à travers une lecture des renver- l’ ISBN / sements opérés par chaque nouvelle « période » par rapport à la précédente. Wright a vécu jusqu’à près de 90 ans et, approches tout au long de sa longue vie, l’architecte américain s’est cinq montré capable de se renouveler d’une manière specta- culaire. Plusieurs « styles » se partagent en effet l’œuvre : Wright, une première période presque Art nouveau, une deuxième Lloyd plus singulière et souvent considérée comme un peu énig- Frank matique, d’une ornementation encore plus foisonnante, / puis, enfin, une période délibérément moderne avec la Treiber production d’icônes de l’architecture, la Maison sur la cascade et le musée Guggenheim. La deuxième approche est consacrée au « côté Daniel Ruskin » de Wright. Le grand historien américain Henry-Russell Hitchcock a déclaré dans son Architecture : XIXe et XXe siècles que ce qui faisait la « profonde diffé- rence » entre Frank Lloyd Wright et Auguste Perret, un autre novateur quasiment de la même génération, était que 7 www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com « l’un avait dans le sang la tradition du néogothique anglais exponentielle de notre environnement, c’est le point par — en bonne part due à ses lectures de Ruskin — tandis lequel les préoccupations de Wright sont étonnamment que l’autre ne l’avait pas ». -

Lecture Handouts, 2013

Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Classs #1 INTRODUCTION & OVERVIEW Introductions Expectations Textbooks Assignments Electronic reserves Research Project Sources History-Theory-Criticism Methods & questions of Architectural History Assignments: Initial Paper Topic form Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Classs #2 ARCHITECTURE OF WWII The World at War (1939-45) Nazi War Machine - Rearming Germany after WWI Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect & responsible for Nazi armaments Autobahn & Volkswagen Air-raid Bunkers, the “Atlantic Wall”, “Sigfried Line”, by Fritz Todt, 1941ff Concentration Camps, Labor Camps, POW Camps Luftwaffe Industrial Research London Blitz, 1940-41 by Germany Bombing of Japan, 1944-45 by US Bombing of Germany, 1941-45 by Allies Europe after WWII: Reconstruction, Memory, the “Blank Slate” The American Scene: Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941 Pentagon, by Berman, DC, 1941-43 “German Village,” Utah, planned by US Army & Erich Mendelsohn Military production in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Akron, Cleveland, Gary, KC, etc. Albert Kahn, Detroit, “Producer of Production Lines” * Willow Run B-24 Bomber Plant (Ford; then Kaiser Autos, now GM), Ypsilanti, MI, 1941 Oak Ridge, TN, K-25 uranium enrichment factory; town by S.O.M., 1943 Midwest City, OK, near Midwest Airfield, laid out by Seward Mott, Fed. Housing Authortiy, 1942ff Wartime Housing by Vernon Demars, Louis Kahn, Oscar Stonorov, William Wurster, Richard Neutra, Walter Gropius, Skidmore-Owings-Merrill, et al * Aluminum Terrace, Gropius, Natrona Heights, PA, 1941 Women’s role in the war production, “Rosie the Riverter” War time production transitions to peacetime: new materials, new design, new products Plywod Splint, Charles Eames, 1941 / Saran Wrap / Fiberglass, etc.