A Retrospective on the Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Did Frank Lloyd Wright Establish a New Canon of American

“ The mother art is architecture. Without an architecture of our own we have no soul of our own civilization.” -Frank Lloyd Wright How did Frank Lloyd Wright establish a new canon of American architecture? Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) •Considered an architectural/artistic genius and THE best architect of last 125 years •Designed over 800 buildings •Known for ‘Prairie Style’ (really a movement!) architecture that influenced an entire group of architects •Believed in “architecture of democracy” •Created an “organic form of architecture” Prairie School The term "Prairie School" was coined by H. Allen Brooks, one of the first architectural historians to write extensively about these architects and their work. The Prairie school shared an embrace of handcrafting and craftsmanship as a reaction against the new assembly line, mass production manufacturing techniques, which they felt created inferior products and dehumanized workers. However, Wright believed that the use of the machine would help to create innovative architecture for all. From your architectural samples, what may we deduce about the elements of Wright’s work? Prairie School • Use of horizontal lines (thought to evoke native prairie landscape) • Based on geometric forms . Flat or hipped roofs with broad overhanging eaves . “Environmentally” set: elevations, overhangs oriented for ventilation . Windows grouped in horizontal bands called ribbon fenestration that used shifting light . Window to wall ratio affected exterior & interior . Overhangs & bays reach out to embrace . Integration with the landscape…Wright designed inside going out . Solid construction & indigenous materials (brick, wood, terracotta, stucco…natural materials) . Open continuous plan & spaces; use of dissolving walls, but connected spaces Prairie School •Designed & used “glass screens” that echoed natural forms •Created Usonian homes for the “masses” Frank Lloyd Wright, Darwin D. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

Starchitect:” Wright Finds His Voice After Being Fired

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 5, Issue 3– Pages 301-318 After the “Starchitect:” Wright Finds his Voice after Being Fired By Michael O'Brien * The term ―Starchitect‖ seems to have originated in the 1940’s to describe a ―film star who has designed a house‖ but of late has been understood as an architect who has risen to celebrity status in the general culture. Louis Sullivan, like Daniel Burnham, might have been considered a ―starchitect.‖ Starchitects are frequently associated with a unique style or approach to architecture and all who work for them, adopt this style as their own as a matter of employment. Frank Lloyd Wright was one of these architects, working under and in the idiom of Louis Sullivan for six years, learning to draw and develop motifs in the style of Louis Sullivan. Frank Lloyd Wright’s firing by Louis Sullivan in 1893 and his rapidly growing family set him on an urgent course to seek his own voice. The bootleg houses, designed outside the contract terms Wright had with Adler and Sullivan caused the separation, likely fueled by both Sullivan and Wright’s ego, which left Wright alone, separated from his ―Lieber Meister‖1 or ―Beloved Master.‖ These early houses by Wright were adaptations of various styles popular in the times, Neo-Colonial for Blossom, Victorian for Parker and Gale, each, as Wright explained were not ―radical‖ because ―I could not follow up on them.‖2 Wright, like many young architects, had not yet codified his ideas and strategies for activating space and form. How does one undertake the search for one’s language of these architectural essentials? Does one randomly pursue a course of trial and error casting about through images that capture one’s attention? Do we restrict our voice to that which has already been voiced in history? Wright’s agenda would have included the merging of space and enclosure with site and nature structured as he understood it from Sullivan’s Ornament. -

Download NARM Member List

Huntsville, The Huntsville Museum of Art, 256-535-4350 Los Angeles, Chinese American Museum, 213-485-8567 North American Reciprocal Mobile, Alabama Contemporary Art Center Los Angeles, Craft Contemporary, 323-937-4230 Museum (NARM) Mobile, Mobile Museum of Art, 251-208-5200 Los Angeles, GRAMMY Museum, 213-765-6800 Association® Members Montgomery, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 334-240-4333 Los Angeles, Holocaust Museum LA, 323-651-3704 Spring 2021 Northport, Kentuck Museum, 205-758-1257 Los Angeles, Japanese American National Museum*, 213-625-0414 Talladega, Jemison Carnegie Heritage Hall Museum and Arts Center, 256-761-1364 Los Angeles, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, 888-488-8083 Alaska Los Angeles, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, 323-957-1777 This list is updated quarterly in mid-December, mid-March, mid-June and Haines, Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center, 907-766-2366 Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, 213-621-1794 mid-September even though updates to the roster of NARM member Kodiak, The Kodiak History Museum, 907-486-5920 Los Angeles, Skirball Cultural Center*, 310-440-4500 organizations occur more frequently. For the most current information Palmer, Palmer Museum of History and Art, 907-746-7668 Los Gatos, New Museum Los Gatos (NUMU), 408-354-2646 search the NARM map on our website at narmassociation.org Valdez, Valdez Museum & Historical Archive, 907-835-2764 McClellan, Aerospace Museum of California, 916-564-3437 Arizona Modesto, Great Valley Museum, 209-575-6196 Members from one of the North American -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

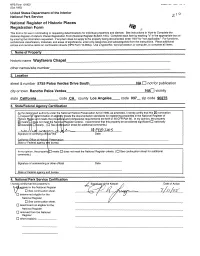

NPS Form 10-900 \M/IVIUJ i ^vy. (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________________ historic name Wayfarers Chapel ________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location ___________________________ street & number 5755 Palos Verdes Drive South_______ NA d not for publication city or town Rancho Palos Verdes________________ NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Los Angeles. code 037_ zip code 90275 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this C3 nomination D request f fr*d; (termination -

Preserving Graycliff:An Examination of the Colors,Fabrics and Furniture of the Frank Lloyd Wright Designed Summer Residence of I

Figure 1. Graycliff exterior. 2001 WAG Postprints—Dallas, Texas Preserving Graycliff:An Examination of the Colors, Fabrics and Furniture of the Frank Lloyd Wright Designed Summer Residence of Isabelle Martin Pamela Kirschner Abstract Information was gathered in a study of the interior color scheme, fabrics and furni- ture of the Frank Lloyd Wright designed house Graycliff. The house is situated on a cliff overlooking Lake Erie in Derby, New York. It was designed by Wright in 1926 for Isabelle Martin, the wife of the industrialist Darwin Martin. Wright designed both freestanding and built-in furniture for the house interior and also suggested colors and fabrics. Extensive written documentation and original photographs found in the archives of the State University of New York at Buffalo have been utilized to determine the colors, materials and furniture original to the house. Physical evidence found on the remaining original furniture, moldings and upholstered pillows provides informa- tion about fi nishes, construction and show cover fabrics. Information on historic methods and materials from the period is provided for comparison with the physi- cal evidence along with scientifi c analysis of fi nishes. The conservation treatment methods are also discussed. This technical and historical information is helpful for conservators and curators to better understand the materials and construction used in Frank Lloyd Wright designs during this time period. It also promotes the proper care and conservation treatment of these objects while preserving original fi nishes and the historic intent of the house. Introduction Graycliff was the summer estate of Isabelle R. and Darwin D. Martin and is located on the cliffs above Lake Erie in Derby, New York, fourteen miles south of Buffalo. -

Preserving the Textile Block at Florida Southern College a Report Prepared for the World Monuments Fund Jeffrey M

Preserving the Textile Block at Florida Southern College A Report Prepared for the World Monuments Fund Jeffrey M. Chusid, Preservation Architect 18 September 2009 ISBN-10: 1-890879-43-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-890879-43-3 © 2011 World Monuments Fund 2 Letter from World Monuments Fund President Bonnie Burnham 4 Letter from Florida Southern President Anne B. Kerr, Ph.D. 5 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 7 Preservation Philosophy 7 History and Significance 10 Ideas behind the System 10 Description of the System 10 Conservation Issues with the System in Earlier Sites 13 Recent Conservation Projects at the Storer, Freeman, and Ennis Houses 14 Florida Southern College 16 A History of Changes 18 Site Conditions and Analysis 19 Contents Prior research and observations 19 WMF Site visit 19 Taxonomy of Conservation Problems in the Textile-Block System 20 Issues and Challenges 22 The Textile-Block System 22 The Block 23 Methodologies 24 Conservation 25 Recommendations 26 Appendix A: Visual Conditions Documentation 29 Appendix B: Team Members 38 3 In April 2009, World Monuments Fund was honored to convene a historic gathering of historians, architects, conservators, craftsmen, and scientists at Florida Southern College to explore Frank Lloyd Wright’s use of ornamental concrete textile block construction. To Wright, this material was a highly expressive, decorative, and practical approach to create monumental yet affordable buildings. Indeed, some of his most iconic structures, including the Ennis House in Los Angeles, utilized the textile block system. However, like so many of Wright’s experiments with materials and engineering, textile block has posed major challenges to generations of building owners, architects, and conservators who have struggled with the system’s material and structural performance. -

2019 – 2020 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2019 – 2020 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT NATIONAL RECIPROCAL SITES MEMBERSHIP PROGRAM THE FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT NATIONAL RECIPROCAL SITES PROGRAM IS AN ALLIANCE OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT ORGANIZATIONS THAT OFFER RECIPROCAL BENEFITS TO PARTICIPATING MEMBERS. Frank Lloyd Wright sites and organizations listed here are independently For questions about the Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites owned, managed and operated. Reciprocal Members are advised to contact Membership Program please contact your institution’s membership sites prior to their visit for tour and site information. Phone numbers and department. Each site / organization may handle processing differently. websites are provided for your convenience. This icon indicates a 10% shop discount. You must present a membership card bearing the “FLWR” identifier to claim these benefits at reciprocal sites. 2019 – 2020 MEMBER BENEFITS ARIZONA THE ROOKERY 209 S LaSalle St Chicago, IL 60604 TALIESIN WEST lwright.org 312.994.4000 12345 N Taliesin Dr Scottsdale, AZ 85259 Beneits: Two complimentary tours franklloydwright.org 888.516.0811 Beneits: Two complimentary admissions to the 90-minute Insights tours. INDIANA Reservations recommended. THE JOHN AND CATHERINE CHRISTIAN HOUSE-SAMARA CALIFORNIA 1301 Woodland Ave West Lafayette, IN 47906 samara-house.org 765.409.5522 HOLLYHOCK HOUSE Beneits: One complimentary tour 4800 Hollywood Blvd Los Angeles, CA 90026 barnsdall.org IOWA Beneits: Two complimentary self-guided tours MARIN COUNTY CIVIC CENTER THE HISTORIC PARK INN HOTEL (CITY NATIONAL BANK AND 3501 -

Frank Lloyd Wright

'SBOL-MPZE8SJHIU )JTUPSJD"NFSJDBO #VJMEJOHT4VSWFZ '$#PHL)PVTF $PNQJMFECZ.BSD3PDILJOE Frank Lloyd Wright Historic American Buildings Survey Sample: F. C. Bogk House Compiled by Marc Rochkind Frank Lloyd Wright: Historic American Buildings Survey, Sample Compiled by Marc Rochkind ©2012,2015 by Marc Rochkind. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form or by any means (including electronic) without permission in writing from the copyright holder. Copyright does not apply to HABS materials downloaded from the Library of Congress website, although it does apply to the arrangement and formatting of those materials in this book. For information about other works by Marc Rochkind, including books and apps based on Library of Congress materials, please go to basepath.com. Introduction The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) was started in 1933 as one of the New Deal make-work programs, to employ jobless architects, draftspeople, and photographers. Its purpose is to document the nation’s architectural heritage, especially those buildings that are in danger of ruin or deliberate destruction. Today, the HABS is part of the National Park Service and its repository is in the Library of Congress, much of which is available online at loc.gov. Of the tens of thousands HABS buildings, I found 44 Frank Lloyd Wright designs that have been digitized. Each HABS survey includes photographs and/or drawings and/or a report. I’ve included here what the Library of Congress had–sometimes all three, sometimes two of the three, and sometimes just one. There might be a single photo or drawing, or, such as in the case of Florida Southern College (in volume two), over a hundred. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Chicago to Fallingwater

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT CHICAGO TO FALLINGWATER MAY 15-27, 2022 TOUR LEADER: STUART BARRIE Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterpiece, Fallingwater (1939) FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT Overview CHICAGO TO FALLINGWATER Academy Travel’s Frank Lloyd Wright from Chicago to Fallingwater tour Tour dates: May 15-27, 2022 offers a unique opportunity to view 16 buildings designed by Wright, including suburban homes, rural villas, churches and commercial offices. Tour leader: Stuart Barrie Inspired by nature, forward looking, varied and highly original, Wright’s works continues to astound us. A journey through Wright’s architecture is Tour Price: $9,870 per person, twin share also a journey through modern America from the ‘Gilded Age’ of the 1890s to ‘mid-century modern’ when American architecture, design, art Single Supplement: $2,120 for sole use of and literature dominated the world stage. double room The tour also visits buildings by Wright’s predecessors, contemporaries Booking deposit: $1,000 per person and followers, including Daniel Burnham, Louis B Sullivan, Mies Van Der Rohe and Norman Forster. We begin with four nights in Chicago, a city Recommended airline: Qantas or United brimming with fine architecture and fine art, and where Wright developed his Prairie Style of architecture. We then travel north to Milwaukee, visiting the SC Johnson Wax Administration Building, and on to Madison, Maximum places: 20 Wisconsin to see some of Wright’s commercial work as well as Taliesin, his beloved estate. Our next stop is Buffalo, near Niagara Falls, to visit the Itinerary: Chicago (4 nights), Milwaukee Darwin Martin complex of houses. Travelling to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, (1 night), Madison (2 nights), Buffalo (2 nights), we conclude the tour with a private in-depth tour of America’s most Pittsburgh (3 nights) famous house, Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. -

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1

Zimmerman House Materials—Final List Binder 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Through 1989” Photocopied articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: from 1956-1989, bulk 1989 Binder 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1990” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Date: 1990 Binder 3—Labeled “Zimmerman House 1991” Photocopied and original articles from magazines and newspapers o Dates: 1991-1992, bulk 1991 Box 1—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Deaccession? Files” Folder: Sotheby’s catalogue—Gagliano violin and sales slip Folder: Slides, photos, receipts, correspondence, appraisal for Gagliano violin and bow. o Date: 1989 Box 2—Labeled “Zimmerman House Archive—Vintage Publications on the Zimmerman House” “The Zimmerman House Historic Structure Report” (2 copies); also includes a press release (not attached) o Date: 1989 “A Classic Usonian: Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1950 House for Isadore J. and Lucille Zimmerman.” General information, labels. o Date: 1990 Folder: “Exhibition: A Classic Usonian: Label Copy.” Also an unattached article; label copy from exhibit appears to be the same as previous item. “Currier Grant Application for National Endowment for the Humanities for Training Zimmerman House Guides.” Also includes unattached correspondence, a docent bulletin, a memorandum, and a priorities evaluation. o Dates: 1990-1991, bulk 1990 Box 3—Labeled “Uncatalogued Materials” Newsclipping about Dr. Zimmerman o Date: undated 2 color photos of exterior of Zimmerman House with inscriptions from Zimmermans on back o Date: 1976 Black and white photo of exterior of Zimmerman House in winter o Date: undated 3 B & W photos of Lucille Zimmerman’s family o Date: undated Postcard with picture of S.C.