Graycliff – a Truly American Story “In His Unshakable Optimism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincoln Logs Inventor John Lloyd Wright | Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation

8/20/2019 Lincoln Logs Inventor John Lloyd Wright | Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation An advertisement for Lincoln Logs, 1925. Courtesy of Period Paper Lincoln Logs Inventor John Lloyd Wright AUGUST 23, 2018 BY MONICA M. SMITH Yes, this popular childhood toy was designed by none other than the son of architect Frank Lloyd Wright! Years ago while conducting research for the Lemelson Center’s Invention at Play exhibition, I was surprised to learn that Lincoln Logs—one of my favorite childhood toys—were designed by John Lloyd Wright, son of world-famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Overshadowed by his father, John has received little attention beyond a brief 1982 biography now available online. And he certainly seemed reticent about telling his own story, instead publicly sharing only a few experiences as part of his short, impressionistic 1946 book about Frank titled My Father Who Is On Earth. https://invention.si.edu/lincoln-logs-inventor-john-lloyd-wright 1/5 8/20/2019 Lincoln Logs Inventor John Lloyd Wright | Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation Left: John Lloyd Wright in Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1921, ICHi-173783. Right: Frank Lloyd Wright with son John Lloyd Wright, undated., i73784. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum Turns out that John was both a successful toy designer and an architect in, dare I say it, his own right. Here is a brief overview of his story, including the origins of those ever-popular Lincoln Logs. Born in 1892, John Kenneth (later changed to Lloyd) Wright was the second of Frank and Catherine Wright’s six children. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J

Architecture Publications Architecture Winter 2008 Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J. Naegele Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/54. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Abstract Why "Wright in Iowa?" Are there ways that Wright's Iowa works are distinguished from his built works elsewhere? Iowa is a typical Midwest state, exceptional in neither general geography nor landscape. The ts ate's urban areas are minor, and Iowa has never been known for its subscription to avant-garde architecture. Its most renowned artist, Grant Wood, painted Iowa's rolling hills and pie-faced people in cartoon-like images that simultaneously champion and question the coalescence of people and place. Indeed, the state's most convincing buildings are found on its farms with their unpretentious, vernacular, agricultural buildings. Disciplines Architectural History and Criticism Comments This article is from Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly 19 (2008): 4–9. Posted with permission. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs/54 a (Photos above and opposite page, top right) The Lowell and Agnes Walter hy "Wright in Iowa?" Are House, "Cedar Rock," Quasqueton, W there ways that Wright's Iowa. -

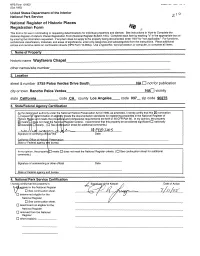

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 \M/IVIUJ i ^vy. (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________________ historic name Wayfarers Chapel ________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location ___________________________ street & number 5755 Palos Verdes Drive South_______ NA d not for publication city or town Rancho Palos Verdes________________ NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Los Angeles. code 037_ zip code 90275 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this C3 nomination D request f fr*d; (termination -

Preserving Graycliff:An Examination of the Colors,Fabrics and Furniture of the Frank Lloyd Wright Designed Summer Residence of I

Figure 1. Graycliff exterior. 2001 WAG Postprints—Dallas, Texas Preserving Graycliff:An Examination of the Colors, Fabrics and Furniture of the Frank Lloyd Wright Designed Summer Residence of Isabelle Martin Pamela Kirschner Abstract Information was gathered in a study of the interior color scheme, fabrics and furni- ture of the Frank Lloyd Wright designed house Graycliff. The house is situated on a cliff overlooking Lake Erie in Derby, New York. It was designed by Wright in 1926 for Isabelle Martin, the wife of the industrialist Darwin Martin. Wright designed both freestanding and built-in furniture for the house interior and also suggested colors and fabrics. Extensive written documentation and original photographs found in the archives of the State University of New York at Buffalo have been utilized to determine the colors, materials and furniture original to the house. Physical evidence found on the remaining original furniture, moldings and upholstered pillows provides informa- tion about fi nishes, construction and show cover fabrics. Information on historic methods and materials from the period is provided for comparison with the physi- cal evidence along with scientifi c analysis of fi nishes. The conservation treatment methods are also discussed. This technical and historical information is helpful for conservators and curators to better understand the materials and construction used in Frank Lloyd Wright designs during this time period. It also promotes the proper care and conservation treatment of these objects while preserving original fi nishes and the historic intent of the house. Introduction Graycliff was the summer estate of Isabelle R. and Darwin D. Martin and is located on the cliffs above Lake Erie in Derby, New York, fourteen miles south of Buffalo. -

The Life and Work of Frank Lloyd Wright

THE LIFE AND WORK OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PART 4 Ages 42 (1909) to 47 (1914) In Italy and Wisconsin Wunderlich PhD website: http://users.etown.edu/w/wunderjt/ Architecture Portfolio 8/28/2018 PART 1: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 0-19 (1867-1886) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube Context: Post Civil War recession. Industrial Revolution. Farm life. Preacher/Musician-Father, Teacher-Mother. Mother’s large influential Unitarian family of Welsh farmers. Nature. Parent’s divorce. Architecture: Froebel schooling (e.g., blocks). Barns/farm-houses (PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube). Organic Architecture roots. PART 2: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 20-33 (1887-1900) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube. Context: Rebuilding Chicago after the Great Fire. Wife Catherine and first five children. Architecture: Architects Joseph Silsbee and Louis Sullivan. Oak Park. Home & Studio. “Organic Architecture” begins. PART 3: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 34-41 (1901-1908) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube. Context: First Japan trip (PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube). Arts & Crafts movements. Six children. Architecture: Prairie Style. Oak Park & River Forest, Unity Temple, Robie House, Larkin Building. PART 4: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 42-47 (1909-1914) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube THIS LECTURE Context: Runs off with Mistress. Lives in Italy (Page MP4 YouTube). Builds Taliesin on family farmland. Mistress murdered. Architecture: Wasmuth Portfolio published(Germany).Taliesin. Many operable windows for health & passive cooling. Sculptures. PART 5: Frank Lloyd Wright Age 48-62 (1915-1929) PDF PPTX-w/audio MP4 YouTube Context: WWI, Roaring 20’s. Short 2nd marriage. Lives 3 yrs in Japan, then California and Wisconsin. -

Oak Park Area Visitor Guide

OAK PARK AREA VISITOR GUIDE COMMUNITIES Bellwood Berkeley Broadview Brookfield Elmwood Park Forest Park Franklin Park Hillside Maywood Melrose Park Northlake North Riverside Oak Park River Forest River Grove Riverside Schiller Park Westchester www.visitoakpark.comvisitoakpark.com | 1 OAK PARK AREA VISITORS GUIDE Table of Contents WELCOME TO THE OAK PARK AREA ..................................... 4 COMMUNITIES ....................................................................... 6 5 WAYS TO EXPERIENCE THE OAK PARK AREA ..................... 8 BEST BETS FOR EVERY SEASON ........................................... 13 OAK PARK’S BUSINESS DISTRICTS ........................................ 15 ATTRACTIONS ...................................................................... 16 ACCOMMODATIONS ............................................................ 20 EATING & DRINKING ............................................................ 22 SHOPPING ............................................................................ 34 ARTS & CULTURE .................................................................. 36 EVENT SPACES & FACILITIES ................................................ 39 LOCAL RESOURCES .............................................................. 41 TRANSPORTATION ............................................................... 46 ADVERTISER INDEX .............................................................. 47 SPRING/SUMMER 2018 EDITION Compiled & Edited By: Kevin Kilbride & Valerie Revelle Medina Visit Oak Park -

2019 – 2020 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2019 – 2020 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT NATIONAL RECIPROCAL SITES MEMBERSHIP PROGRAM THE FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT NATIONAL RECIPROCAL SITES PROGRAM IS AN ALLIANCE OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT ORGANIZATIONS THAT OFFER RECIPROCAL BENEFITS TO PARTICIPATING MEMBERS. Frank Lloyd Wright sites and organizations listed here are independently For questions about the Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites owned, managed and operated. Reciprocal Members are advised to contact Membership Program please contact your institution’s membership sites prior to their visit for tour and site information. Phone numbers and department. Each site / organization may handle processing differently. websites are provided for your convenience. This icon indicates a 10% shop discount. You must present a membership card bearing the “FLWR” identifier to claim these benefits at reciprocal sites. 2019 – 2020 MEMBER BENEFITS ARIZONA THE ROOKERY 209 S LaSalle St Chicago, IL 60604 TALIESIN WEST lwright.org 312.994.4000 12345 N Taliesin Dr Scottsdale, AZ 85259 Beneits: Two complimentary tours franklloydwright.org 888.516.0811 Beneits: Two complimentary admissions to the 90-minute Insights tours. INDIANA Reservations recommended. THE JOHN AND CATHERINE CHRISTIAN HOUSE-SAMARA CALIFORNIA 1301 Woodland Ave West Lafayette, IN 47906 samara-house.org 765.409.5522 HOLLYHOCK HOUSE Beneits: One complimentary tour 4800 Hollywood Blvd Los Angeles, CA 90026 barnsdall.org IOWA Beneits: Two complimentary self-guided tours MARIN COUNTY CIVIC CENTER THE HISTORIC PARK INN HOTEL (CITY NATIONAL BANK AND 3501 -

Larkin Historic District Appendix A

1 Appendix A – Architectural, Historical, and Cultural Significance Larkin Historic District I. Introduction The buildings, streets, and railroads associated with the Larkin Co. constitute a nationally significant cultural landscape. Their character, materials, craftsmanship, design, scale, mass, and relationship to each other and the surrounding city render them valuable to the city, state, and nation. They also stand as the embodiment of the vision, ideals, and drive of singular individuals whose influence is appreciated and felt to the present day: John D. Larkin, Darwin D. Martin, Elbert Hubbard, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Robert J. Reidpath. While built during the railroad era to accommodate a manufacturing and distribution company of national scope, many of the buildings have been successfully adapted to a new era and for other uses, such as offices, over the past 15 years. The structures and sites included are: • 726 Exchange St., Larkin R/S/T Building (1911-1912) • 290 Larkin St., Larkin L/M Building (1904) • 635 Seneca St., Larkin I Building, Larkin Power House (1902-1904) • 680 Seneca St., site of Larkin A Building, Larkin Administration Building (1904-1906) • 696 Seneca St., Larkin Men’s Club, former Sacred Heart Church rectory (circa 1890) • 701 Seneca St., Larkin B/C/D/Dx/E/F/G/H/J/K/N/O Buildings, Larkin Factory (1898-1913) • 239 Van Rensselear St., Larkin U Building, Duk-It Building (circa 1893) II. Geographic & Site Significance The Larkin Co. buildings are located in The Hydraulics neighborhood. Buffalo’s first manufacturing district, and a nationally important industrial heritage site, the neighborhood was established in 1827 by Reuben Bostwick Heacock one mile east of downtown Buffalo. -

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cc1668 No online items Guide to the Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167 Jonathan Manton; Gurudarshan Khalsa Archive of Recorded Sound 2018 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/ars Guide to the Howe Collection of ARS.0167 1 Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167 Language of Material: Multiple languages Contributing Institution: Archive of Recorded Sound Title: Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0167 Physical Description: 438 box(es)352 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1838-2002 Abstract: The Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature documents the development of the music industry, mainly in the United States. The largest known collection of its kind, it contains material about the manufacture of pianos, organs, and mechanical musical instruments. The materials include catalogs, books, magazines, correspondence, photographs, broadsides, advertisements, and price lists. The collection was created, and originally donated to the University of Maryland, by Richard J. Howe. It was transferred to the Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound in 2015 to support the Player Piano Project. Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94305-3076”. Language of Material: The collection is primarily in English. There are additionally some materials in German, French, Italian, and Dutch. Arrangement The collection is divided into the following six separate series: Series 1: Piano literature. Series 2: Organ literature. Series 3: Mechanical musical instruments literature. Series 4: Jukebox literature. Series 5: Phonographic literature. Series 6: General music literature. Scope and Contents The Howe Musical Instrument Literature Collection consists of over 352 linear feet of publications and documents comprising more than 14,000 items. -

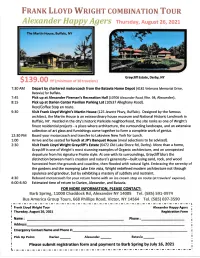

Frank Lloyd Wright Combo Tour

Fnervx LroYD WrucHT CoMBINATIoN Toun Graycliff Estate. Derby, NY 139.00 ,t {minimum of 3o traveters} 7:30 AM Depart by chartered motorcoach from the Batavia Home Depot (atat veterans Memorial Drive, Batavialfor Buffalo. 7:45 Pick up at Alexander Fireman's Recreation Hall (10708 Alexander Road /Rte. 98, Alexander). 8:15 Pick up at Darien Center Pavilion Parking Lot (10537 Alleghany Road). Rest/Coffee Stop en route. 9:30 Visit Frank Lloyd Wright's Martin House (125 Jewett Pkwy, Buffalo). Designed by the famous architect, the Martin House is an extraordinary house museum and National Historic Landmark in Buffalo, NY. Nestled in the city's historic Parkside neighborhood, the site ranks as one of Wright's finest residential projects - a place where architecture, the surrounding landscape, and an extensive collection of art glass and furnishings come together to form a complete work of genius. 12:30 PM Board your motorcoach and transfer to Lakeview New York for Lunch. 1:00 Arrive and be seated for lunch at JPs Banquet House (meal selections to be advised). 2:3A Visit Frank Lloyd Wright Graycliffs Estate (6472 Old Lake Shore Rd, Derby). More than a home, Graycliff is one of Wright's most stunning examples of Organic architecture, and an unexpected departure from his signature Prairie style. At one with its surroundings, Graycliff blurs the distinction between man's creation and nature's generosity-built using sand, rock, and wood harvested from the grounds and coastline, then flooded with natural light. Embracing the serenity of the gardens and the sweeping Lake Erie vista, Wright redefined modern architecture not through opulence and grandeur, but by exhibiting a mastery of subtlety and restraint.