Starchitect:” Wright Finds His Voice After Being Fired

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stupid Starchitect Debate

THE STUPID STARCHITECT DEBATE “Here’s to the demise of Starchitecture!” wrote Beverly Willis, in The New York Timesrecently. Willis, through her foundation, has done much to promote the value of architecture. But like many critics of celebrity architecture, she gets it wrong: “In my 55-plus years of practice and involvement in architecture, I have witnessed the birth and — what I hope will soon be — the demise of the star architect.” The last few years has seen the rise of the snarky, patronizing term “starchitect,” (a term I refuse to use outside this context, much to the annoyance of editors seeking click-bait). But big-name architects creating spectacular, expensive buildings that from time to time prove to be white elephants have always been with us. Think Greek temples, Hindu Palaces, Chinese gardens, and monumental Washington, DC. The Times clearly struck a nerve by running a starchitecture story of utter laziness by author and emeritus professor Witold Rybczynski. That story led to a “Room for Debate” forum offering a variety of solicited points of view, and another more recent forum in which the Times asked readers to respond to a thoughtful letter by Peggy Deamer, an architect (and friend) who teaches at Yale. WHINING ABOUT CELEBRITY ARCHITECTURE I have written a great deal about celebrity architects as well as practitioners of what Rybczynski calls “locatecture.” He names no architects that stick to their own city, however, which says to me he doesn’t really care about the kind of practitioner he claims to celebrate. He’d rather just complain about flashy architecture than deeply examine it. -

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower by KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower BY KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO We were just getting used to the idea of seeing a sensuous Zaha Hadid building on the corporate-modernist boulevard that is Manhattan’s Park Avenue, but looks like we’ll have to keep dreaming. An invited competition to design a new Park Avenue office building for L&L Holdings and Lemen Brothers Holdings pitted starchitect against starchitect (with a shortlist including Hadid and Rem Koolhaas’s firm OMA). In the end, Lord Norman Foster came out victorious. “Our aim is to create an exceptional building, both of its time and timeless, as well as being respectful of this context,” said Norman Foster in a statement, according to The Architects’ Newspaper. Foster described the building as “for the city and for the people that will work in it, setting a new standard for office design and providing an enduring landmark that befits its world-famous location.” The winning design (pictured left) is a three-tiered, 625,000-square-foot tower. With sky-high landscaped terraces, flexible floor plates, a sheltered street-level plaza, and LEED certification, the building does seem to reiterate some of the same principles seen in the Lever House and Seagram Building, Park Avenue’s current office tower icons, but with markedly updated standards. Only time will tell if Foster’s building can achieve the same timelessness as its mid-century predecessors, a feat that challenged a slew of architects as Park Avenue cultivated its corporate identity in the 1950s and 60s. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" If Property Is Not Part of a Multiple Property Listing)

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name State of Illinois Center other names/site number James R. Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 100 West Randolph Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Department of Natural Resources - SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Starchitect NSF- 1010624

Starchitect NSF- 1010624 Summative Evaluation for Space Science Institute By Kate Haley Goldman Patricia A. Montano Emily Craig Erin Wilcox Audience Viewpoints Consulting January 2016 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES 3 LIST OF FIGURES 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT BACKGROUND 6 STARCHITECT GAME CONTEXT 8 METHODOLOGY AND SAMPLE 8 Game-wide Sample 9 SAMPLE: CONTROLLED STUDY 14 WHAT WAS THE NATURE OF GAME PLAY? 17 FINDINGS: CONTROLLED STUDY 25 SCIENCE CONFIDENCE 25 NO CHANGE IN ASTRONOMY INTEREST 28 SELF-PERCEPTION OF KNOWLEDGE 29 MEASURED KNOWLEDGE 30 LEARNED FROM THE GAME 34 MOTIVATION FOR PLAYING 35 REFLECTION ON LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE PROJECT 42 REFERENCES 49 APPENDIX A: PRE SURVEY 51 APPENDIX B: POST SURVEY 59 APPENDIX C: TELEPHONE INTERVIEW 68 Starchitect Summative Evaluation 2 Audience Viewpoints Consulting List of Tables Table 1: Where Players Found Out about Starchitect ..................................................................... 9 Table 2: Age Provided Game-Wide ............................................................................................................ 9 Table 3: Gender provided Game-wide ................................................................................................. 12 Table 4: Gender Game-wide....................................................................................................................... 12 Table 5: Starchitect Players are More Knowledgeable about Science than the General Public ........................................................................................................................................................... -

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

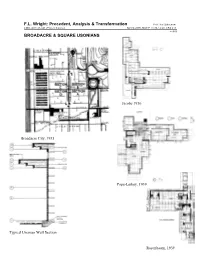

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

The Avant-Garde Architecture of Three 21St Century Universal Art Museums

ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS by Leslie Elaine Reid APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Richard Brettell, Chair ___________________________________________ Nils Roemer ___________________________________________ Maximilian Schich ___________________________________________ Charissa N. Terranova Copyright 2019 Leslie Elaine Reid All Rights Reserved ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS by LESLIE ELAINE REID, MLA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES - AESTHETIC STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank, in particular, two people in Paris for their kindness and generosity in granting me interviews, providing electronic links to their work, and emailing me data on the Louvre-Lens for my dissertation. Adrién Gardère of studio adrien gardère and Catherine Mosbach of mosbach paysagists gave hours of their time and provided invaluable insight for this dissertation. And – even after I had returned to the United States, they continued to email documents that I would need. March 2019 iv ABU DHABI, LENS, AND LOS ANGELES: THE AVANT-GARDE ARCHITECTURE OF THREE 21ST CENTURY UNIVERSAL ART MUSEUMS Leslie Elaine Reid, PhD The University of Texas at Dallas, 2019 ABSTRACT Supervising Professor: Richard Brettell Rooted in the late 18th and 19th century idea of the museum as a “library of past civilizations,” the universal or encyclopedic museum attempts to cover as much of the history of mankind through “art” as possible. -

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright 1. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g04297 5. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.il0039 Some designs and executed buildings by Frank Frederick C. Robie House, 5757 Woodlawn Avenue, Lloyd Wright, architect Chicago, Cook County, IL 2. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g01871 House ("Bogk House") for Frederick C. Bogk, 2420 North Terrace Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Stone lintel] http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/r?pp/hh:@field(DOCID+@lit(PA1690)) Fallingwater, State Route 381 (Stewart Township), Ohiopyle vicinity, Fayette County, PA 3. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/gsc.5a25495 Guggenheim Museum, 88th St. & 5th Ave., New York City. Under construction III. 6. 4. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c11252 http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/r?ammem/alad:@field(DOCID+@lit(h19 Frank Lloyd Wright, Baroness Hilla Rebay, and 240)) Solomon R. Guggenheim standing beside a model of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum] / Midway Gardens, interior, Chicago, IL Margaret Carson #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6 #7 PREVIOUS NEXT RECORDS LIST NEW SEARCH HELP Item 10 of 375 How to obtain copies of this item TITLE: Some designs and executed buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, architect CALL NUMBER: Illus in NA737.W7 A4 1917 (Case Y) [P&P] REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZC4-4297 (color film copy transparency) LC-USZ62-116098 (b&w film copy neg.) SUMMARY: Silhouette of building with steeples on cover of Japanese journal issue devoted to Frank Lloyd Wright, with Japanese and English text. MEDIUM: 1 print : woodcut(?), color. CREATED/PUBLISHED: [1917] NOTES: Illus. -

Wisconsin Magazine * of History

f"*"'J' I' \ Wisconsin t Magazine * of History TKe La Follette Committee ani, the C.l.O. JEROLD S. AUERBACH Tke Grand OU Regiment STEPHEN Z. STARR Frank Lloyd Wright in Wisconsin RICHARD W. E. PERRIN William Howard Taft and Cannonism STANLEY D. SOLVICK Proceedings of the One Hundred and Eigkteenth Annual Meeting Published by the State Historical Society oj Wisconsin / Vol. XLVIII, No. 1 / Autumn, 1964 THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN LESLIE H. FISHEL, JR., Director Officers SCOTT M. CUTLIP, President HERBERT V. KOHLER, Honorary Vice-President JOHN C. GEILFUSS, First Vice-President E. E. HOMSTAD, Treasurer CLIFFORD D. SWANSON, Second Vice-President LESLIE H. FISHEL, JR., Secretary Board of Curators Ex-Officio JOHN W. REYNOLDS, Governor of the State MRS. DENA A. SMITH, State Treasurer ROBERT C. ZIMMERMAN, Secretary of State FRED H. HARRINGTON, President of the University ANGUS B. ROTHWELL, Superintendent of Public Instruction MRS. JOSEPH C. GAMROTH, President of the Women's Auxiliary Term Expires, 1965 GEORGE BANTA, JR. PHILIP F. LA FOLLETTE WILLIAM F. STARK CEDRIC A. VIG Menasha Madison Pewaukee Rhinelander KENNETH W. HAAGENSEN ROBERT B. L. MURPHY MILO K. SWANTON CLARK WILKINSON Oconomowoc Madison Madison Baraboo GEORGE HAMPEL, JR. FOSTER B. PORTER FREDERICK N. TROWBRIDGE ANTHONY WISE Des Moines Bloomington Green Bay Hayward Term Expires, 1966 E. DAVID CRONON W. NORMAN FITZGERALD JOHN C. GEILFUSS JAMES A. RILEY Madison Milwaukee Milwaukee Eau Claire SCOTT M. CUTLIP EDWARD FROMM MRS. HOWARD T. GREENE CLIFFORD D. SWANSON Madison Hamburg Genesee Depot Stevens Point MRS. ROBERT E. FRIEND ROBERT A. GEHRKE ROBERT L. PIERCE Hartland Ripon Menomonie Term Expires, 1967 THOMAS H. -

Space of Continuity: Frank Lloyd Wright's Destruction of the Box And

Space of Continuity: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Destruction of the Box and Modern Conceptions of Space Late 19th-early 20th century America was an era of confluence of science, phi- losophy and religion: a contemporary polemic that equated religion (belief based on faith) with science (knowledge based on empirical data of physical phe- nomena). Modernity in 20th century America would be shaped by a pervasive theosophical atmosphere that coupled science with religion to cause a recon- sideration of mental/spiritual relationships and a redefinition of space/time concepts. Theosophy’s introduction of Eastern metaphysics to Western culture revealed possibilities of an inner self with respect to the outer being and opened the way to conceive of inner space, or interiority, and as a result interior space in buildings. To follow is a reconsideration of Wright’s work with respect to the theosophical and occult influences that guided his thinking. His contribution to today’s notion of architecture as a space of continuity will be demonstrated through case studies of his work beginning with the early Dana House (begun in 1899) to the Guggenheim Museum (completed after his death in 1959). EUGENIA VICTORIA ELLIS THE RED SQUARE Drexel University Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) began his practice in 1893 after being fired for “moonlighting” near the end of his five year contract with Adler and Sullivan, one of the then-preeminent Chicago architecture firms. Originally hired to draw the delicate ornamental details of the Auditorium Building interior, another ornamental masterpiece Wright had detailed just debuted at the World’s Columbian Exposition. -

A Retrospective on the Journey

| | EDUCATIONFRANK LLOYD ADVOCACYWRIGHT BUILDING PRESERVATION CONSERVANCY SPRING 2014 / VOLUME 5 / ISSUES 1 & 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE A Retrospective on the Journey Guest Editor: Ron Scherubel Past, Present, Future: The Conservancy at 25 2014 CONFERENCE Phoenix, Arizona | Oct. 29 – Nov. 2 Stay for a great rate in the legendary Wright- influenced Arizona Biltmore. Tour seldom-seen houses by Wright and other acclaimed architects. Get a private behind-the-scenes look at Taliesin celebrating years of saving wright West. Attend presentations and panels with world- 25 renowned Wright scholars, including a keynote speech by New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman. And cap it all off with a Gala Dinner, silent auction, Wright Spirit Awards ceremony, and much more! Register beginning in FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY June at savewright.org or call 312.663.5500 C ON T Editor’s Welcome: OK, What’s Next? 2 EN 2 Executive Editor’s Message: The Power of Community President’s Message: The Challenge Ahead 3 TS 4 Wright and Historic Preservation in the United States, 1950-1975 11 The Origins of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy 16 A Day in the Conservancy Office 20 Retrospect and Prospect 22 The ‘Saves’ in SaveWright 28 The Importance of the David and Gladys Wright House PEDRO E. GUERRERO (1917-2012) 30 Saving the David and Gladys Wright House The cover photo of this issue was taken by 38 A New Book Explores Additions to Iconic Buildings Pedro E. Guerrero, Frank Lloyd Wright’s 42 A Future for the Past trusted photographer. Guerrero was just 22 46 Up Close and Personal in 1939 when Wright took an amused look at his portfolio of school assignments and 49 Executive Director’s Letter: For the Next 25 hired him on the spot to document the con- struction at Taliesin West. -

Film and Architecture: Discovering the Self-Reflection of Frank Capra And

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2000 Film and architecture: Discovering the self-reflection of rF ank Capra and Frank Lloyd Wright through contextual analysis Marie Lynore Kohler University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Kohler, Marie Lynore, "Film and architecture: Discovering the self-reflection of rF ank Capra and Frank Lloyd Wright through contextual analysis" (2000). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1120. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/c7iq-fh8b This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiaice, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor qualify illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction.