The Avant-Garde Architecture of Three 21St Century Universal Art Museums

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stupid Starchitect Debate

THE STUPID STARCHITECT DEBATE “Here’s to the demise of Starchitecture!” wrote Beverly Willis, in The New York Timesrecently. Willis, through her foundation, has done much to promote the value of architecture. But like many critics of celebrity architecture, she gets it wrong: “In my 55-plus years of practice and involvement in architecture, I have witnessed the birth and — what I hope will soon be — the demise of the star architect.” The last few years has seen the rise of the snarky, patronizing term “starchitect,” (a term I refuse to use outside this context, much to the annoyance of editors seeking click-bait). But big-name architects creating spectacular, expensive buildings that from time to time prove to be white elephants have always been with us. Think Greek temples, Hindu Palaces, Chinese gardens, and monumental Washington, DC. The Times clearly struck a nerve by running a starchitecture story of utter laziness by author and emeritus professor Witold Rybczynski. That story led to a “Room for Debate” forum offering a variety of solicited points of view, and another more recent forum in which the Times asked readers to respond to a thoughtful letter by Peggy Deamer, an architect (and friend) who teaches at Yale. WHINING ABOUT CELEBRITY ARCHITECTURE I have written a great deal about celebrity architects as well as practitioners of what Rybczynski calls “locatecture.” He names no architects that stick to their own city, however, which says to me he doesn’t really care about the kind of practitioner he claims to celebrate. He’d rather just complain about flashy architecture than deeply examine it. -

Starchitect:” Wright Finds His Voice After Being Fired

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 5, Issue 3– Pages 301-318 After the “Starchitect:” Wright Finds his Voice after Being Fired By Michael O'Brien * The term ―Starchitect‖ seems to have originated in the 1940’s to describe a ―film star who has designed a house‖ but of late has been understood as an architect who has risen to celebrity status in the general culture. Louis Sullivan, like Daniel Burnham, might have been considered a ―starchitect.‖ Starchitects are frequently associated with a unique style or approach to architecture and all who work for them, adopt this style as their own as a matter of employment. Frank Lloyd Wright was one of these architects, working under and in the idiom of Louis Sullivan for six years, learning to draw and develop motifs in the style of Louis Sullivan. Frank Lloyd Wright’s firing by Louis Sullivan in 1893 and his rapidly growing family set him on an urgent course to seek his own voice. The bootleg houses, designed outside the contract terms Wright had with Adler and Sullivan caused the separation, likely fueled by both Sullivan and Wright’s ego, which left Wright alone, separated from his ―Lieber Meister‖1 or ―Beloved Master.‖ These early houses by Wright were adaptations of various styles popular in the times, Neo-Colonial for Blossom, Victorian for Parker and Gale, each, as Wright explained were not ―radical‖ because ―I could not follow up on them.‖2 Wright, like many young architects, had not yet codified his ideas and strategies for activating space and form. How does one undertake the search for one’s language of these architectural essentials? Does one randomly pursue a course of trial and error casting about through images that capture one’s attention? Do we restrict our voice to that which has already been voiced in history? Wright’s agenda would have included the merging of space and enclosure with site and nature structured as he understood it from Sullivan’s Ornament. -

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower by KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower BY KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO We were just getting used to the idea of seeing a sensuous Zaha Hadid building on the corporate-modernist boulevard that is Manhattan’s Park Avenue, but looks like we’ll have to keep dreaming. An invited competition to design a new Park Avenue office building for L&L Holdings and Lemen Brothers Holdings pitted starchitect against starchitect (with a shortlist including Hadid and Rem Koolhaas’s firm OMA). In the end, Lord Norman Foster came out victorious. “Our aim is to create an exceptional building, both of its time and timeless, as well as being respectful of this context,” said Norman Foster in a statement, according to The Architects’ Newspaper. Foster described the building as “for the city and for the people that will work in it, setting a new standard for office design and providing an enduring landmark that befits its world-famous location.” The winning design (pictured left) is a three-tiered, 625,000-square-foot tower. With sky-high landscaped terraces, flexible floor plates, a sheltered street-level plaza, and LEED certification, the building does seem to reiterate some of the same principles seen in the Lever House and Seagram Building, Park Avenue’s current office tower icons, but with markedly updated standards. Only time will tell if Foster’s building can achieve the same timelessness as its mid-century predecessors, a feat that challenged a slew of architects as Park Avenue cultivated its corporate identity in the 1950s and 60s. -

CHAMPS-ELYSEES ROLL OR STROLL from the Arc De Triomphe to the Tuileries Gardens

CHAMPS-ELYSEES ROLL OR STROLL From the Arc de Triomphe to the Tuileries Gardens Don’t leave Paris without experiencing the avenue des Champs-Elysées (shahnz ay-lee-zay). This is Paris at its most Parisian: monumental side- walks, stylish shops, grand cafés, and glimmering showrooms. This tour covers about three miles. If that seems like too much for you, break it down into several different outings (taxis roll down the Champs-Elysées frequently and Métro stops are located every 3 blocks). Take your time and enjoy. It’s a great roll or stroll day or night. The tour begins at the top of the Champs-Elysées, across a huge traffic circle from the famous Arc de Triomphe. Note that getting to the arch itself, and access within the arch, are extremely challenging for travelers with limited mobility. I suggest simply viewing the arch from across the street (described below). If you are able, and you wish to visit the arch, here’s the informa- tion: The arch is connected to the top of the Champs-Elysées via an underground walkway (twenty-five 6” steps down and thirty 6” steps back up). To reach this passageway, take the Métro to the not-acces- sible Charles de Gaulle Etoile station and follow sortie #1, Champs- Elysées/Arc de Triomphe signs. You can take an elevator only partway up the inside of the arch, to a museum with some city views. To reach the best views at the very top, you must climb the last 46 stairs. For more, see the listing on page *TK. -

A Quick Tour of Paris 1

A quick tour of Paris 1 A QUICK TOUR OF PARIS 12 – 17 April 2016 Text by John Biggs © 2016 Images by John Biggs and Catherine Tang © 2016 A quick tour of Paris 2 A QUICK TOUR OF PARIS 22 hours and four plane changes see us arrive at Charles De Gaulle Airport whacked out. We have booked on a river cruise down the Rhone but have taken a five day tour of Paris before joining the cruise. We are met by a girl from the Dominican Republic who came to Paris a year ago with no French and massive ambitions. Four jobs later she is fluent in French, has an excellent job in tourism and is seeking more worlds to conquer. She takes us to a large car with a taciturn driver who is to take us to our hotel but something funny is going on: we have been going for much longer than expected, we pass through the grimmest industrial parts of Paris in silence. At one major intersection, police cars and motor cycles, light flashing, sirens wailing, weave in and around us. We look uneasily at each other: this is the month of the bombings. But wailing police sirens is a sound that is as Parisian as the Eiffel Tower, we are to discover. After an hour and some we finally arrive at Hotel Duminy-Vendome in the centre of Paris and our driver turns out to have excellent English, which he now uses freely. I had been studying French on line with Duolingo to 52% fluency (try it if you want to learn a language, it’s fantastic) but that doesn’t seem much use here. -

220,000 €400 Million 4,500

Building for Art’s Sake World-class museums no longer stake their reputations on art and artifacts alone; the museum building itself must be viewed as an architectural treasure. Along with surging visitor numbers and swelling collections, this trend is driving a spate of major museum projects in New York, New York, USA; London, England; and theEd ge Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE). Te projects expand, The Louvre Abu Dhabi, designed by French architect Jean Nouvel, is move or build new branches of some of the world’s leading muse- slated for a December 2015 opening. ums—and face challenges ranging from unusual building sites to allegations of labor abuses. Te €400 million Louvre Abu Dhabi designed by French architect Jean Nouvel, slated for a December 2015 opening, and the US$800 million Guggenheim Abu Dhabi designed by U.S. architect Frank Gehry, scheduled to open in 2017, are prime examples. Branches of the original Guggenheim and Louvre museums in New York and Paris, France, respectively, the proj- ects are central components of the UAE government’s planned “cultural district” on Saadiyat Island. Because the two museums will be surrounded by water on three sides, engineering hurdles are substantial. Te largest challenge facing Saadiyat’s three museum proj- ects—the Zayed National Museum is scheduled to open in 2016, with assistance from the British Museum in London—is putting to rest international concern about widespread abuses of migrant workers, including poor living conditions, unpaid wages and forced labor. “I therefore call on the UAE government, but also on all companies involved in the Saadiyat project—including [the] Louvre, British Museum and Guggenheim—to ensure that any form of mistreatment is addressed and that all migrants can fully enjoy their human rights,” Barbara Lochbihler, chair of the European Parliament’s subcom- mittee on human rights, said in December 2013. -

VISITOR FIGURES 2015 the Grand Totals: Exhibition and Museum Attendance Numbers Worldwide

SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide VISITOR FIGURES 2015 The grand totals: exhibition and museum attendance numbers worldwide THE DIRECTORS THE ARTISTS They tell us about their unlikely Six artists on the exhibitions blockbusters and surprise flops that made their careers U. ALLEMANDI & CO. PUBLISHING LTD. EVENTS, POLITICS AND ECONOMICS MONTHLY. EST. 1983, VOL. XXV, NO. 278, APRIL 2016 II THE ART NEWSPAPER SPECIAL REPORT Number 278, April 2016 SPECIAL REPORT VISITOR FIGURES 2015 Exhibition & museum attendance survey JEFF KOONS is the toast of Paris and Bilbao But Taipei tops our annual attendance survey, with a show of works by the 20th-century artist Chen Cheng-po atisse cut-outs in New attracted more than 9,500 visitors a day to Rio de York, Monet land- Janeiro’s Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil. Despite scapes in Tokyo and Brazil’s economic crisis, the deep-pocketed bank’s Picasso paintings in foundation continued to organise high-profile, free Rio de Janeiro were exhibitions. Works by Kandinsky from the State overshadowed in 2015 Russian Museum in St Petersburg also packed the by attendance at nine punters in Brasilia, Rio, São Paulo and Belo Hori- shows organised by the zonte; more than one million people saw the show National Palace Museum in Taipei. The eclectic on its Brazilian tour. Mgroup of exhibitions topped our annual survey Bernard Arnault’s new Fondation Louis Vuitton despite the fact that the Taiwanese national muse- used its ample resources to organise a loan show um’s total attendance fell slightly during its 90th that any public museum would envy. -

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

THE STÄDEL MUSEUM 700 Years of Art History

PRESS RELEASE THE STÄDEL MUSEUM 700 Years of Art History Established in 1815 as a civic foundation by the banker and merchant Johann Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie Friedrich Städel, the Städel Museum is regarded as the oldest and most renowned Dürerstraße 2 museum foundation in Germany. The diversity of the collection provides an almost 60596 Frankfurt am Main Telefon +49(0)69-605098-170 complete overview of 700 years of European art history, from the early fourteenth Fax +49(0)69-605098-111 century across the Renaissance, the Baroque and Modernism right up to the [email protected] www.staedelmuseum.de immediate present. Altogether the Städel collection comprises some 3,000 paintings, PRESS DOWNLOADS 600 sculptures, more than 4,000 photographs and more than 100,000 drawings and www.staedelmuseum.de graphic works. Its highlights include works by such artists as Lucas Cranach, Albrecht PRESS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS Dürer, Sandro Botticelli, Rembrandt van Rijn, Jan Vermeer, Claude Monet, Pablo Axel Braun, Head Tel. +49(0)69-605098-170 Picasso, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckmann, Alberto Giacometti, Francis Bacon, Fax +49(0)69-605098-188 [email protected] Gerhard Richter, Wolfgang Tillmans and Corinne Wasmuht. The focus of the Städel Silke Janßen Museum’s work, alongside collecting and conserving, consists in scholarly research Telefon +49(0)69-605098-234 Fax +49(0)69-605098-188 into the museum’s holdings, as well as in the organization of exhibitions based on the [email protected] works in its care. A further central concern is to put the art across to specific target Karoline Leibfried groups; this aspect addresses both the contents of the collection but also general Telefon +49(0)69-605098-212 Fax +49(0)69-605098-188 questions of art, and is aimed at a diversified public. -

Schools Distributing Yalla This Map Is Not to Scale & Is

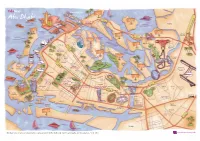

Guggenheim Abu Dhabi Saadiyat Zayed Island Port Louvre Abu Dhabi Al Zayed National Museum Mina Ramhan E12 Cranleigh Island Abu Dhabi Al Bahya Sheikh Khalifa Lulu Bridge Island Abu Dhabi - Dubai Road Dhow Yas Island Emirates Harbour Al Jubail Island Park Zoo Al E12 Corniche Repton School Zahiyah Abu Dhabi Al Maryah Island Yas Abu Dhabi Waterworld Mall Zeera Al Danah Island Ferrari World E10 Abu Dhabi Al Muna Primary School Al Reem Island Al Hosn Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan St Umm Yifenah Madinat Island Yas Marina Zayed Circuit Mangrove Al Manhal Al National Park E22 Dhafrah Samaliyah Sheikh Rashid BinThe Saeed Pearl St (Airport Rd) Island Primary School Abu Dhabi Al Marina International Al Nahyan Airport Heritage Village Al Khalidiyah Sas Al Al Nakhl Al Musalla Al Etihad Zafranah Al Rayhan American Brighton Emirates Community 3. Al Mushrif School College Palace Khalifa School of Mushrif Central Park Al Bateen Park Al Yasmina Abu Dhabi Al Rehaan Secondary School British School Al Sheikh Zayed Bridge E10 School Al Rowdah American International Khalifa Al Khubeirah Al Khubairat Muntazah Masdar Al Khaleej Arabi St (30th) School of Abu Dhabi City City Khor Al E22 Royal Stables Zayed Maqta’a Al Ras Sports City Al Mushrif ADNEC Al Akhdar Al Ain Zoo Sheikh Zayed Al Maqta Bridge Cricket Stadium Umm Al Nar Al Bateen Al Maqta Coconut Al Bateen Zayed Island Boat Yard University Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque Al Musaffah Bridge Zayed City Al Hudayriat Island The British International School Abu Dhabi E11 Musaffah Schools Distributing Yalla This map is not to scale & is intended as a representation of Abu Dhabi only. -

Brightspark London Paris Rome 10 Day European Student Tour

LONDON, PARIS & ROME 10 Days | European Student Tour TOUR SNAPSHOT Experience the culture, history and architecture of London, Paris and Rome on this 10-day educational student tour. Satisfy your inner Hufflepuff with a photo at Platform 9 3/4, discover the stunning gardens and lavish rooms in the Palace of Versailles, and toss a coin in the Trevi Fountain to ensure a trip back to Rome. This trip will broaden the minds of your students and will leave them with a passion for travel. WHATS INCLUDED: Guided Tours of: London, Paris, Rome Site Visits: Buckingham Palace, British Museum, Tate Modern Gallery, King’s Cross Station, Eiffel Tower, Sainte-Chapelle, Champs Élysées, Musée du Louvre, Palace of Versailles, Colosseum, Vatican, Sistine Chapel, St. Peter’s Basilica Local Accommodations Tour Leader 3 Star Centrally Located Hotels Transportation Meals Flights, Private Motor Breakfasts, Dinners Coach, Public Transportation WHY BRIGHTSPARK? PUTTING YOUR EXPERIENCE FIRST • Guaranteed Flights and Hotels – We confirm the booking of flights and hotels when you submit your deposit to avoid last minute hiccups. • Centrally Located Accommodations – Save hours avoiding long commutes and maximize your time in destination with hotels within the city limits. • Private Tours – Personalize your class trip to suit your needs and be assured that your students will never be joined with another group. • Go, Discover, Inspire – You are not a tourist but a traveler. We will expose you and your students to the soul of the destination and ignite their sense of wonder. EXPERTS IN STUDENT TRAVEL 95% 60+ Our local partnerships allow for personalized OF TEACHERS YEARS OF tours that are a hybrid of traditional and LOVE OUR TRAVEL unconventional. -

LVMH 2017 Annual Report

2017 ANNUAL REPORT Passionate about creativity Passionate about creativity W H O W E A R E A creative universe of men and women passionate about their profession and driven by the desire to innovate and achieve. A globally unrivalled group of powerfully evocative brands and great names that are synonymous with the history of luxury. A natural alliance between art and craftsmanship, dominated by creativity, virtuosity and quality. A remarkable economic success story with more than 145,000 employees worldwide and global leadership in the manufacture and distribution of luxury goods. A global vision dedicated to serving the needs of every customer. The successful marriage of cultures grounded in tradition and elegance with the most advanced product presentation, industrial organization and management techniques. A singular mix of talent, daring and thoroughness in the quest for excellence. A unique enterprise that stands out in its sector. Our philosophy: passionate about creativity LVMH VALUES INNOVATION AND CREATIVITY Because our future success will come from the desire that our new products elicit while respecting the roots of our Maisons. EXCELLENCE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICE Because we embody what is most noble and quality-endowed in the artisan world. ENTREPRENEURSHIP Because this is the key to our ability to react and our motivation to manage our businesses as startups. 2 • 3 Selecting leather at Berluti. THE LVMH GROUP 06 Chairman’s message 12 Responsible initiatives in 2017 16 Interview with the Group Managing Director 18 Governance and Organization 20 Our Maisons and business groups 22 Performance and responsibility 24 Key fi gures and strategy 26 Talent 32 Environment 38 Responsible partnerships 40 Corporate sponsorship BUSINESS GROUP INSIGHTS 46 Wines & Spirits 56 Fashion & Leather Goods 66 Perfumes & Cosmetics 76 Watches & Jewelry 86 Selective Retailing 96 LVMH STORIES PERFORMANCE MEASURES 130 Stock market performance measures 132 Financial performance measures 134 Non-fi nancial performance measures 4 • 5 LVMH 2017 .