Neil Levine's the Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J

Architecture Publications Architecture Winter 2008 Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J. Naegele Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/54. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Abstract Why "Wright in Iowa?" Are there ways that Wright's Iowa works are distinguished from his built works elsewhere? Iowa is a typical Midwest state, exceptional in neither general geography nor landscape. The ts ate's urban areas are minor, and Iowa has never been known for its subscription to avant-garde architecture. Its most renowned artist, Grant Wood, painted Iowa's rolling hills and pie-faced people in cartoon-like images that simultaneously champion and question the coalescence of people and place. Indeed, the state's most convincing buildings are found on its farms with their unpretentious, vernacular, agricultural buildings. Disciplines Architectural History and Criticism Comments This article is from Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly 19 (2008): 4–9. Posted with permission. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs/54 a (Photos above and opposite page, top right) The Lowell and Agnes Walter hy "Wright in Iowa?" Are House, "Cedar Rock," Quasqueton, W there ways that Wright's Iowa. -

Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia: preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia: preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19369. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Frank Lloyd Wright's

Usonia, N E W Y O R K PROOF 1 Usonia, N E W Y O R K Building a Community with Frank Lloyd Wright ROLAND REISLEY with John Timpane Foreword by MARTIN FILLER PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS, NEW YORK PROOF 2 PUBLISHED BY This publication was supported in part with PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS funds from the New York State Council on the 37 EAST SEVENTH STREET Arts, a state agency. NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 Special thanks to: Nettie Aljian, Ann Alter, Amanda For a free catalog of books, call 1.8... Atkins, Janet Behning, Jan Cigliano, Jane Garvie, Judith Visit our web site at www.papress.com. Koppenberg, Mark Lamster, Nancy Eklund Later, Brian McDonald, Anne Nitschke, Evan Schoninger, © Princeton Architectural Press Lottchen Shivers, and Jennifer Thompson of Princeton All rights reserved Architectural Press—Kevin C. Lippert, publisher Printed in China First edition Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Reisley, Roland, – No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any Usonia, New York : building a community with manner without written permission from the publisher Frank Lloyd Wright / Roland Reisley with John except in the context of reviews. Timpane ; foreword by Martin Filler. p. cm. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify isbn --- owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected . Usonian houses—New York (State)—Pleasant- in subsequent editions. ville. Utopias—New York (State)—Pleasantville— History. Architecture, Domestic—New York All photographs © Roland Reisley unless otherwise (State)—Pleasantville. Wright, Frank Lloyd, indicated. –—Criticism and interpretation. i. Title: Usonia. ii. Timpane, John Philip. iii. -

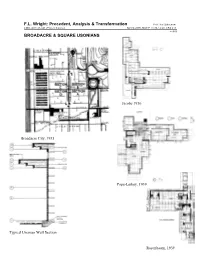

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright 978-2-86364-338-9 Cinq Approches ISBN / Approches Cinq

frank lloydwright DANIEL TREIBER DANIEL 978-2-86364-338-9 PARENTHÈSES ISBN cinq approches / approches cinq Wright, Lloyd Frank / Treiber Daniel www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com WRIGHT, JUSQU’À NOUS Dans ce nouveau livre que je consacre à Frank Lloyd Wright, je me propose d’aborder son œuvre selon cinq approches différentes. 978-2-86364-338-9 L’essai introductif est une présentation de ensemble de ses travaux à travers une lecture des renver- l’ ISBN / sements opérés par chaque nouvelle « période » par rapport à la précédente. Wright a vécu jusqu’à près de 90 ans et, approches tout au long de sa longue vie, l’architecte américain s’est cinq montré capable de se renouveler d’une manière specta- culaire. Plusieurs « styles » se partagent en effet l’œuvre : Wright, une première période presque Art nouveau, une deuxième Lloyd plus singulière et souvent considérée comme un peu énig- Frank matique, d’une ornementation encore plus foisonnante, / puis, enfin, une période délibérément moderne avec la Treiber production d’icônes de l’architecture, la Maison sur la cascade et le musée Guggenheim. La deuxième approche est consacrée au « côté Daniel Ruskin » de Wright. Le grand historien américain Henry-Russell Hitchcock a déclaré dans son Architecture : XIXe et XXe siècles que ce qui faisait la « profonde diffé- rence » entre Frank Lloyd Wright et Auguste Perret, un autre novateur quasiment de la même génération, était que 7 www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com « l’un avait dans le sang la tradition du néogothique anglais exponentielle de notre environnement, c’est le point par — en bonne part due à ses lectures de Ruskin — tandis lequel les préoccupations de Wright sont étonnamment que l’autre ne l’avait pas ». -

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frank_... Frank Lloyd Wright From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, Frank Lloyd Wright 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1000 structures and completed 532 works. Wright believed in designing structures which were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by his design for Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, Born Frank Lincoln Wright skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright June 8, 1867 also designed many of the interior Richland Center, Wisconsin elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright Died April 9, 1959 (aged 91) authored 20 books and many articles and Phoenix, Arizona was a popular lecturer in the United Nationality American States and in Europe. His colorful Alma mater University of Wisconsin- personal life often made headlines, most Madison notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known Buildings Fallingwater during his lifetime, Wright was recognized Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1991 by the American Institute of Museum Architects as "the greatest American Johnson Wax Headquarters [1] architect of all time." Taliesin Taliesin West Robie House Contents Imperial Hotel, Tokyo Darwin D. -

Film and Architecture: Discovering the Self-Reflection of Frank Capra And

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2000 Film and architecture: Discovering the self-reflection of rF ank Capra and Frank Lloyd Wright through contextual analysis Marie Lynore Kohler University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Kohler, Marie Lynore, "Film and architecture: Discovering the self-reflection of rF ank Capra and Frank Lloyd Wright through contextual analysis" (2000). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1120. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/c7iq-fh8b This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiaice, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor qualify illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Communities by Design in THIS ISSUE

EDUCATION | ADVOCACY | PRESERVATION THE MAGAZINE OF THE FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY THE MAGAZINE OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY FALL 2016 / VOLUME 7 ISSUE 2 FALL IN THIS ISSUE Communities by Design Guest Editor: Jane King Hession editor’s MESSAGE communities by design Communities can take many forms and mean different things to different people. Vary though they may, all communities are fundamentally alike in that they are all composed of individuals who, col- lectively, share common interests, characteristics or geography. The whole of a community comprises its parts. Frank Lloyd Wright was no stranger to this concept: for decades he lived and worked at the center of the Taliesin Fellowship, a community of his own creation. However, as the essays in this issue make clear, Wright also explored the idea of community—at multiple scales—in his architecture and planning. In his article on the politics of community, Robert Wojtowicz considers the philosophical divide between Wright and his longtime friend (and sometime foe), cultural critic Lewis Mumford, on the subject. As Wojtowicz describes, the two men often argued their polar positions on the pages of the country’s leading publications. The roots of one of Wright’s best known communities, Usonia in Pleasantville, New York, are revisited by an original owner in the community, Roland Reisley. In ad- ABOUT THE EDITOR dition to taking a backward glance at its origins, Reisley also reveals the impact of Wright’s vision on successive generations of residents. Neil Levine describes Wright’s application of “the power of ge- ometry” to create community at the scale of the individual house and the residential block. -

Taliesin Architects Reorganized

the living legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright TALIESIN TaliesinArchitects FELLOWS Reorganized NEWSLETTER ® by CEO Jim Goulka, NUMBER 12, JULY 15, 2003 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation oing architecture. Designing buildings. Improving the landscape by one’s own creations. Satisfying client needs. DDThat is what many people came to Taliesin to learn. Some were fortunate enough to learn directly from the master. Others learned at one remove from the architects who remained after 1959. But the point, for them, was to do architecture. Mr. Wright was emphatic that for an architectural design, there can only be one vision, one person responsible. Assistants could help, of course—Mr. Wright clearly needed the superb assistance from the apprentices to accomplish the prodigious output of the 1950s—but, at the top, architecture is a solo act. Many of the alumni have cited this reason for departing Taliesin, most notably The announcement of Taliesin Architects reorganization, the Edgar Tafel, as described in his book Apprentice to inevitable outcome of market economy, has sur- Genius. prised and shaken the organic architectural After Mr. Wright’s death, Taliesin Associated Architects completed Mr. Wright’s projects and led community. In business since the death of Frank the practice into the future. For many years, the firm Lloyd Wright in 1959, the eleven architects who was profitable and helped maintain the Foundation and School. Since the early 90’s however, the firm comprised the organization will now enter the has suffered; one or two major projects provided the field as private practioners albeit continuing in major income, but required additional staffing to complete. -

Protecting Usonia a Homeowner’S and Site Manager’S Resource for Understanding and Addressing Common Preservation Concerns in Frank Lloyd Wright’S Usonian Home

PROTECTING USONIA A HOMEOWNER’S AND SITE MANAGER’S RESOURCE FOR UNDERSTANDING AND ADDRESSING COMMON PRESERVATION CONCERNS IN FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S USONIAN HOME A THESIS SUBMITTED ON THE 29TH DAY OF APRIL 2018 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PRESERVATION STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PRESERVATION STUDIES BY EMILY BUTLER APPROVED: __________________ Professor John Stubbs Director 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Personal Statement……………………..………………………………………………………………………………..3 Primary Goals…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Chapter 2 Understanding Wright……………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Historical Background…………………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Organic Architecture As Described By Wright……………………………………………………………….13 Usonia: Concept to Reality……………………………………………………………………………………………16 Usonian Forms: Module and Unit System…………………………………………………………………….25 Common Building Materials and Elements……………………………………………………………………30 A Note on Sustainability……………………………………………………………………………………………….32 Chapter 3 Case Studies in Preserving Usonian Homes………………………………………………………………33 Case Study: Herbert Jacobs House……………………………………………………………..…………………33 Case Study: Kentuck Knob – I.N. & Bernardine Hagan House………………………………………..40 Case Study: Rosenbaum House…………………………………………………………………………………….57 Case Study: Pope-Leighey House………………………………………………………………………………….66 Chapter 4 Homeowners -

NEWSLETTER NUMBER 1, OCTOBER 5, 2000 Taliesin�Fellows Present�The�Newsletter

TALIESIN FELLOWS ® NEWSLETTER NUMBER 1, OCTOBER 5, 2000 TaliesinFellows PresenttheNewsletter ith this, our inaugural issue, Taliesin Fellows begin a long-awaited publishing venture, the Taliesin Fellows W Newsletter. Initial circulation will be subscribers of the Journal of the Taliesin Fellows as well as former apprentices. More than eight hundred copies will be distributed. Bill Patrick, current president of Northern California Taliesin Fellows, will serve as editor for the project, which will be published quarterly by The Midglen Studio in Woodside, CA. Its endeavor is to serve the mission of the Fellows in fur- thering the philosophy and principles of Frank Lloyd Wright and present news of Fellows’ activities as well as independent views on architecture with emphasis on the ongoing work of former Taliesin apprentices as well as views by the faculty and stu- dents at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. Tourofthe Approved by the board of directors of the Taliesin Fel- HannaHouse lows at their June meeting in Los Angeles, the Newsletter will be an independent voice for organic architecture, and the Norcal Fellows visit to the Hanna views of the editor and writers will be those of the authors, not House at Stanford is set for Sunday, necessarily endorsed by the Fellows Board of Directors or the November 5, 2000 at 11:00 a.m. Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. This tour will accommodate up to Taliesin Fellows Brad Storrer of Alta Loma, CA, Milton 28 participants and will be booked Stricker of Seattle and Frank Laraway of Silverhill, AL will serve on a first-come basis until October as staff contributors for the Newsletter.