Authenticity and the Popular Appeal of Frank Lloyd Wright Daniel J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Did Frank Lloyd Wright Establish a New Canon of American

“ The mother art is architecture. Without an architecture of our own we have no soul of our own civilization.” -Frank Lloyd Wright How did Frank Lloyd Wright establish a new canon of American architecture? Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) •Considered an architectural/artistic genius and THE best architect of last 125 years •Designed over 800 buildings •Known for ‘Prairie Style’ (really a movement!) architecture that influenced an entire group of architects •Believed in “architecture of democracy” •Created an “organic form of architecture” Prairie School The term "Prairie School" was coined by H. Allen Brooks, one of the first architectural historians to write extensively about these architects and their work. The Prairie school shared an embrace of handcrafting and craftsmanship as a reaction against the new assembly line, mass production manufacturing techniques, which they felt created inferior products and dehumanized workers. However, Wright believed that the use of the machine would help to create innovative architecture for all. From your architectural samples, what may we deduce about the elements of Wright’s work? Prairie School • Use of horizontal lines (thought to evoke native prairie landscape) • Based on geometric forms . Flat or hipped roofs with broad overhanging eaves . “Environmentally” set: elevations, overhangs oriented for ventilation . Windows grouped in horizontal bands called ribbon fenestration that used shifting light . Window to wall ratio affected exterior & interior . Overhangs & bays reach out to embrace . Integration with the landscape…Wright designed inside going out . Solid construction & indigenous materials (brick, wood, terracotta, stucco…natural materials) . Open continuous plan & spaces; use of dissolving walls, but connected spaces Prairie School •Designed & used “glass screens” that echoed natural forms •Created Usonian homes for the “masses” Frank Lloyd Wright, Darwin D. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

The 20Th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright National Locator Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois

The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright National Locator Unity Temple, Oak Park, Illinois 87.800° W 87.795° W 87.790° W Erie St N Grove Ave Grove N 41.8902° N, 87.7947° W Ontario St 41.8901° N, 87.7992° W E E 41.890° N 41.890° N Austin Garden Park Scoville Park N Euclid Ave Euclid N N Linden Ave Linden N Forest Ave Forest N Oak Park Ave Park Oak N N Kenilworth Ave Kenilworth N Lake St Unity Temple ! 41.888° N 41.888° N E 41.8878° N, 87.7995° W E North Blvd 41.8874° N, 87.7946° W South Blvd 41.886° N 41.886° N Home Ave Home S Grove Ave Grove S S Euclid Ave Euclid S S Clinton Ave Clinton S S Wesley Ave Wesley S S Oak Park Ave Park Oak S S Kenilworth Ave Kenilworth S 87.800° W 87.795° W Pleasant St 87.790° W Nominated National Historic Projection: Lambert Conformal Conic 1:4,500 Green Space/Park Datum: North American Datum 1983 Property Landmark Production Date: October 2015 0 100 Meters ! Gould Center, Department of Geography ¹ Buffer Zone Center Point Buildings The Pennsylvania State University Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois Frederick C. Robie House, Chicago, Illinois 87.600° W 87.598° W 87.596° W Ave Kimbark S 87.594° W 87.592° W S Woodlawn Ave Woodlawn S E 57th St 41.791° N 41.791° N S Kimbark Ave Kimbark S 41.7904° N, 87.5972° W E41.7904 N, 87.5957° W S Ellis Ave Ellis S E S Kenwood Avenue Kenwood S Frederick C. -

Neil Levine's the Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright

The Avery Review Joseph M. Watson – The Antinomies of Usonia: Neil Levine’s The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright In 1925 Frank Lloyd Wright introduced a neologism to readers of the Dutch Citation: Joseph M. Watson, “The Antinomies of Usonia: Neil Levine’s The Urbanism of Frank journal Wendingen. This new term—Usonian—would soon become synony- Lloyd Wright,’” in the Avery Review 25 (September mous with Wright’s late-career architecture and the socio-spatial regime he 2017), http://www.averyreview.com/issues/25/the- antinomies-of-usonia. envisioned to encompass those works. He casually inserted his coinage into an essay titled “In the Cause of Architecture: The Third Dimension,” which revisited the thesis of his 1901 “The Art and Craft of the Machine” to argue that if the Machine (always, for Wright, with a capital M) could be properly domesticated, it would become a means for overcoming the dehumanizing tendencies of industrialism and the stultifying effects of stylistic revivalism. After characterizing the Renaissance as a misguided project akin to aesthetic miscegenation—“a mongrel admixture of all the styles of the world”—Wright offered a prediction: “Here in the United States may be seen the final Usonian degradation of that ideal—ripening by means of the Machine for destruction by the Machine.” [1] Without explicitly defining his novel modifier, Wright [1] Frank Lloyd Wright, “In the Cause of Architecture: The Third Dimension” (1925), in Bruce Brooks nevertheless elliptically clarified Usonian’s signification. If American artists and Pfeiffer, ed., Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, architects eschewed their misguided fascination with “European backwash,” vol. -

Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J

Architecture Publications Architecture Winter 2008 Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J. Naegele Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/54. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Abstract Why "Wright in Iowa?" Are there ways that Wright's Iowa works are distinguished from his built works elsewhere? Iowa is a typical Midwest state, exceptional in neither general geography nor landscape. The ts ate's urban areas are minor, and Iowa has never been known for its subscription to avant-garde architecture. Its most renowned artist, Grant Wood, painted Iowa's rolling hills and pie-faced people in cartoon-like images that simultaneously champion and question the coalescence of people and place. Indeed, the state's most convincing buildings are found on its farms with their unpretentious, vernacular, agricultural buildings. Disciplines Architectural History and Criticism Comments This article is from Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly 19 (2008): 4–9. Posted with permission. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs/54 a (Photos above and opposite page, top right) The Lowell and Agnes Walter hy "Wright in Iowa?" Are House, "Cedar Rock," Quasqueton, W there ways that Wright's Iowa. -

Wright in Wisconsin

Wright in Wisconsin Walk in Frank Lloyd Wright's footsteps to discover the architect's inspiration for design and the foundation of a true legacy. Born and raised in Wisconsin, Wright rooted many of his design principals in the landscape of his surroundings. Join the Martin House travel team as we discover Wright's home state and many of his designs including: Taliesin, Wright's famed home, studio and school for many years; the Jacobs House, the S.C. Johnson building, Annunciation Church, the Unitarian Meeting House, and more! Participants will enjoy guided tours, a taste of local cuisine and motor coach transportation through Wisconsin's beautiful landscape. Please see below for more detailed information on the places we will be visiting in Wisconsin. The Fred B. Jones House | Penwern (1900-03) Lake Delavan, Wisconsin Designed as a summer home for Oak Park businessman Fred B. Jones, this estate consists of four structures: a main house, boathouse, gate lodge and stable, which were built on a 10-acre site with 600 feet of lakefront and a commanding view of Delavan Lake. Penwern is privately owned and open to the public only for special Frank Lloyd Wright-related events. The Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church (1956-61) Wauwatosa, Wisconsin Located in a suburb of Milwaukee, this church was one of Frank Lloyd Wright's last major commissions; construction was completed after the architect’s death. The basic design of the church is inspired by the architect’s reinterpretation of two traditional Byzantine forms: the Greek cross and the dome. American System-Built Homes (1915-17) Milwaukee, Wisconsin Throughout his career, Frank Lloyd Wright took special interest in designing beautiful yet affordable homes for moderate-to- low-income families. -

JOHNSON WAX Building I. G. FARBEN Offices Site

Johnson Wax Building I. G. Farben Offices Frank Lloyd Wright Hans Poelzig Racine, Wisconsin Site Frankfurt, Germany, 1936-39 c. 1928-31 the site of the two buildings are vastly different; the johnson wax building is in a suburben area and takes un the entire block on which it is located. Con- versely, the ig farben building reads as a building in a landscape, the scale of the site is much larger than wright’s. Both building’s however are part of a larger complex of buildings. Prairie/streamline international era Social context Both buildings were built for rapidly expanding companies: IG Farben, at the time, was the largest conglomerate for dyes, chemicals and drugs and Johnson Wax, later SC Johnson. adam morgan danny sheng Johnson Wax Building I. G. Farben Offices Frank Lloyd Wright Hans Poelzig Racine, Wisconsin Composition Frankfurt, Germany, 1936-39 c. 1928-31 Both buildings are horizontally dominated compositions research tower office towers administration building connecting wing entrance hall building is almost bilaterally symmetrical Bilateral symmetry entry is similar to that of Unity Temple and Robie House. The Entry is on the transverse axis along entry is hidden from view and which the building is bilaterally symmetri- approached on the transverse cal. This classical approach is further axis, this leads to a low dark enforced by the “temple-like” portico on space just prior to entry which the front of the building opens up into a well lit expan- “temple Front” entrance sive space making the entry adam morgan danny sheng Johnson Wax Building I. G. -

Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia: preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia: preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19369. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Frank Lloyd Wright's

Usonia, N E W Y O R K PROOF 1 Usonia, N E W Y O R K Building a Community with Frank Lloyd Wright ROLAND REISLEY with John Timpane Foreword by MARTIN FILLER PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS, NEW YORK PROOF 2 PUBLISHED BY This publication was supported in part with PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS funds from the New York State Council on the 37 EAST SEVENTH STREET Arts, a state agency. NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 Special thanks to: Nettie Aljian, Ann Alter, Amanda For a free catalog of books, call 1.8... Atkins, Janet Behning, Jan Cigliano, Jane Garvie, Judith Visit our web site at www.papress.com. Koppenberg, Mark Lamster, Nancy Eklund Later, Brian McDonald, Anne Nitschke, Evan Schoninger, © Princeton Architectural Press Lottchen Shivers, and Jennifer Thompson of Princeton All rights reserved Architectural Press—Kevin C. Lippert, publisher Printed in China First edition Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Reisley, Roland, – No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any Usonia, New York : building a community with manner without written permission from the publisher Frank Lloyd Wright / Roland Reisley with John except in the context of reviews. Timpane ; foreword by Martin Filler. p. cm. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify isbn --- owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected . Usonian houses—New York (State)—Pleasant- in subsequent editions. ville. Utopias—New York (State)—Pleasantville— History. Architecture, Domestic—New York All photographs © Roland Reisley unless otherwise (State)—Pleasantville. Wright, Frank Lloyd, indicated. –—Criticism and interpretation. i. Title: Usonia. ii. Timpane, John Philip. iii. -

Loving Frank

Loving Frank by John Burnham Schwartz Based on the novel by Nancy Horan Escape Artists Draft of: 10/13/09 Lionsgate Entertainment OVER A BLACK SCREEN: THE SOUND OF HAMMERING. EXT. NEW YORK, GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM - DAY (1958) A long, still WIDE SHOT of the museum’s facade: a temple of sculptural perfection. A checker CAB rolls down Fifth Avenue. Then a 1957 CADILLAC, followed by a late 1950’s New York City BUS. TWO MEN in fedoras and suits stroll through frame, stopping briefly to stare up at the building. We PRESS FORWARD into the space where the men just were, closer to the building, CLOSER, passing through the walls... INT. GUGGENHEIM, ATRIUM - CONTINUOUS Inside. WORKMEN and islands of SCAFFOLDING punctuate the vast open atrium. Ethereal light pours down from the huge skylight above. The building is still unfinished. SUPER: 1958. The HAMMERING continues, louder now, mixed with other sounds of CONSTRUCTION. One by one, the workmen stop hammering, doff their caps and stand at respectful attention. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, 91 and still arrogantly handsome, dressed in a black broad-brimmed hat and dark suit, stands in the center of the atrium, surveying the space and light. Pleased, but not satisfied. Seeing something that we are not seeing. He nods perfunctorily at the workmen and begins to walk slowly up the long, spiralling RAMP. The workmen stare after him -- the greatest architect of their time -- then return to work. INT. GUGGENHEIM, RAMP - CONTINUOUS Alone, slowly, Frank ascends the ramp. Looking critically at things -- the quality of plasterwork, cavities in the walls and ceilings where lights will be -- but also, the higher he goes, the more he seems to be entering another state of mind, a place of his own. -

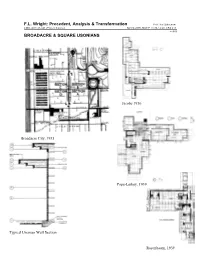

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C.