Frank Lloyd Wright's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RACE, SPACE, and PLACE: the RELATION BETWEEN ARCHITECTURAL MODERNISM, POST-MODERNISM, URBAN PLANNING, and GENTRIFICATION Keith A

RACE, SPACE, AND PLACE: THE RELATION BETWEEN ARCHITECTURAL MODERNISM, POST-MODERNISM, URBAN PLANNING, AND GENTRIFICATION Keith Aoki * [Cite as: 20 Fordham Urb. L.J. 699 (1993)] Introduction Gentrification in United States urban housing markets of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s continues to be a controversial and complex phenomenon. [FN1] During the past twenty years, gentrification's effects on the core cities of the U.S. have been analyzed and evaluated many times over. [FN2] Descriptions of gentrification have spanned the ideological *700 spectrum, from laudatory embraces of gentrification as the solution to urban decline to denunciatory critiques of gentrification as another symptom of the widening gulf between the haves and the have- nots in America. [FN3] This Article critiques gentrification, adding an additional explanatory element to the ongoing account of the dynamics of American cities in the 1990s. The additional element is the relevance of a major aesthetic realignment in architecture and urban planning from a modernist to a post-modernist ideology in the 1970s and 1980s. This shift involved an aesthetic and economic revaluation of historical elements in older central city buildings, which accelerated the rate of gentrification, displacement, and abandonment. This Article describes how certain shifts in the aesthetic ideology [FN4] of urban planners and architects affected suburban and urban spatial distribution in the United States during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These ideological shifts arose from deeply embedded American attitudes toward city and rural life that had emerged in American town planning and architectural theory and practice by the mid-nineteenth century. Part I of this Article examines the emergence of an anti-urban Arcadian strand in nineteenth century American town planning rhetoric. -

Neil Levine's the Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright

The Avery Review Joseph M. Watson – The Antinomies of Usonia: Neil Levine’s The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright In 1925 Frank Lloyd Wright introduced a neologism to readers of the Dutch Citation: Joseph M. Watson, “The Antinomies of Usonia: Neil Levine’s The Urbanism of Frank journal Wendingen. This new term—Usonian—would soon become synony- Lloyd Wright,’” in the Avery Review 25 (September mous with Wright’s late-career architecture and the socio-spatial regime he 2017), http://www.averyreview.com/issues/25/the- antinomies-of-usonia. envisioned to encompass those works. He casually inserted his coinage into an essay titled “In the Cause of Architecture: The Third Dimension,” which revisited the thesis of his 1901 “The Art and Craft of the Machine” to argue that if the Machine (always, for Wright, with a capital M) could be properly domesticated, it would become a means for overcoming the dehumanizing tendencies of industrialism and the stultifying effects of stylistic revivalism. After characterizing the Renaissance as a misguided project akin to aesthetic miscegenation—“a mongrel admixture of all the styles of the world”—Wright offered a prediction: “Here in the United States may be seen the final Usonian degradation of that ideal—ripening by means of the Machine for destruction by the Machine.” [1] Without explicitly defining his novel modifier, Wright [1] Frank Lloyd Wright, “In the Cause of Architecture: The Third Dimension” (1925), in Bruce Brooks nevertheless elliptically clarified Usonian’s signification. If American artists and Pfeiffer, ed., Frank Lloyd Wright: Collected Writings, architects eschewed their misguided fascination with “European backwash,” vol. -

Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J

Architecture Publications Architecture Winter 2008 Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Daniel J. Naegele Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ arch_pubs/54. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright in Iowa Abstract Why "Wright in Iowa?" Are there ways that Wright's Iowa works are distinguished from his built works elsewhere? Iowa is a typical Midwest state, exceptional in neither general geography nor landscape. The ts ate's urban areas are minor, and Iowa has never been known for its subscription to avant-garde architecture. Its most renowned artist, Grant Wood, painted Iowa's rolling hills and pie-faced people in cartoon-like images that simultaneously champion and question the coalescence of people and place. Indeed, the state's most convincing buildings are found on its farms with their unpretentious, vernacular, agricultural buildings. Disciplines Architectural History and Criticism Comments This article is from Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly 19 (2008): 4–9. Posted with permission. This article is available at Iowa State University Digital Repository: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/arch_pubs/54 a (Photos above and opposite page, top right) The Lowell and Agnes Walter hy "Wright in Iowa?" Are House, "Cedar Rock," Quasqueton, W there ways that Wright's Iowa. -

Architectural Styles/Types

Architectural Findings Summary of Architectural Trends 1940‐70 National architectural trends are evident within the survey area. The breakdown of mid‐20th‐ century styles and building types in the Architectural Findings section gives more detail about the Dayton metropolitan area’s built environment and its place within national architectural developments. In American Architecture: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, Cyril Harris defines Modern architecture as “A loosely applied term, used since the late 19th century, for buildings, in any of number of styles, in which emphasis in design is placed on functionalism, rationalism, and up‐to‐date methods of construction; in contrast with architectural styles based on historical precedents and traditional ways of building. Often includes Art Deco, Art Moderne, Bauhaus, Contemporary style, International Style, Organic architecture, and Streamline Moderne.” (Harris 217) The debate over traditional styles versus those without historic precedent had been occurring within the architectural community since the late 19th century when Louis Sullivan declared that form should follow function and Frank Lloyd Wright argued for a purely American expression of design that eschewed European influence. In 1940, as America was about to enter the middle decades of the 20th century, architects battled over the merits of traditional versus modern design. Both the traditional Period Revival, or conservative styles, and the early 20th‐century Modern styles lingered into the 1940s. Period revival styles, popular for decades, could still be found on commercial, governmental, institutional, and residential buildings. Among these styles were the Colonial Revival and its multiple variations, the Tudor Revival, and the Neo‐Classical Revival. As the century progressed, the Colonial Revival in particular would remain popular, used as ornament for Cape Cod and Ranch houses, apartment buildings, and commercial buildings. -

Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia: preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia: preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19369. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19369 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Looking for Usonia : Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's Post-1935 Residential Designs As Generators of Cultural Landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University

Masthead Logo Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2006 Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes William Randall Brown Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brown, William Randall, "Looking for Usonia : preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes" (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18982. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Looking for Usonia: Preserving Frank Lloyd Wright's post-1935 residential designs as generators of cultural landscapes by William Randall Brown A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Architectural Studies Program of Study Committee: Arvid Osterberg, Major Professor Daniel Naegele Karen Quance Jeske Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright ©William Randall Brown, 2006. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate C of I ege Iowa State University This i s to certify that the master' s thesis of V~illiam Randall Brown has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University :atures have been redact` 111 LIST OF TABLES iv ABSTRACT v INTRODUCTION 1 LITERATURE REVIEW 5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The state of Usonia 8 A brief history of Usonia 9 The evolution of Usonian design 13 Preserving Usonia 19 Toward a cultural landscape 21 METHODOLOGY 26 CASE STUDIES: HOUSE MUSEUMS ON PRIVATE LAND No. -

Architecture Overview and Activities

Educational Material Architecture Overview and Activities What is architecture? As defined by Merriam-Webster architecture is: 1. the art or science of building, specifically: the art or practice of designing and building structures and especially habitable ones. 2. a: formation or construction resulting from or as if from a conscious act (the architecture of the garden) b: a unifying or coherent form or structure (the novel lacks architecture) 3. architectural product or work. 4. a method or style of building. 5. the manner in which the components of a computer or computer system are organized and integrated Architectural style refers to the visual appearance of a building and not its function. Style is often influenced by values and aspirations held by a society or a community. Certain designs may serve as metaphors or symbols of what a particular group of people value, of what they consider important. For example, when the Pilgrims first settled in Massachusetts in 1620 they built structures that served their immediate needs: shelter and places of worship. Creating these particular buildings reflected their collective desire for a new home (building a house creates a feeling of permanence and stability) and freedom to worship as they liked. As more people settled in America they brought their own cultural styles and ideas which have continued to influence architectural design. Who Builds Great Buildings? Most of the world’s great buildings have been designed by architects. But there are many other buildings, including many homes, which were built by builders with no architectural training. These builders have sometimes used published plans created by architects or have created their own. -

Architectural Findings

Architectural Findings Summary of Architectural Trends 1940‐70 National architectural trends are evident within the survey area. The breakdown of mid‐20th‐ century styles and building types in the Architectural Findings section gives more detail about the Dayton metropolitan area’s built environment and its place within national architectural developments. In American Architecture: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, Cyril Harris defines Modern architecture as “A loosely applied term, used since the late 19th century, for buildings, in any of number of styles, in which emphasis in design is placed on functionalism, rationalism, and up‐to‐date methods of construction; in contrast with architectural styles based on historical precedents and traditional ways of building. Often includes Art Deco, Art Moderne, Bauhaus, Contemporary style, International Style, Organic architecture, and Streamline Moderne.” (Harris 217) The debate over traditional styles versus those without historic precedent had been occurring within the architectural community since the late 19th century when Louis Sullivan declared that form should follow function and Frank Lloyd Wright argued for a purely American expression of design that eschewed European influence. In 1940, as America was about to enter the middle decades of the 20th century, architects battled over the merits of traditional versus modern design. Both the traditional Period Revival, or conservative styles, and the early 20th‐century Modern styles lingered into the 1940s. Period revival styles, popular for decades, could still be found on commercial, governmental, institutional, and residential buildings. Among these styles were the Colonial Revival and its multiple variations, the Tudor Revival, and the Neo‐Classical Revival. As the century progressed, the Colonial Revival in particular would remain popular, used as ornament for Cape Cod and Ranch houses, apartment buildings, and commercial buildings. -

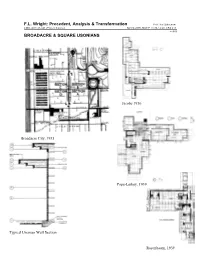

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Historic Architectural Treasures

TOUR Laramie & Albany County, Wyoming Historic architectural treasures of the gem city of the plains TOUR Laramie & Albany County, Wyoming Welcome! Once upon a time, kings and queens embarked upon royal These turbulent early years of the Gem City of the Plains (a tours to visit the distant corners of their realm. Today we invite nickname bestowed in the early 1870s by the publisher of a you to walk no more than a few short blocks to meet Laramie’s local newspaper) left a colorful legacy that continues to attract special brand of “royalty” – magnificent Victorian, Queen visitors to Laramie’s historic downtown, its museums, and those Anne, and Tudor homes, the crown jewels of our town’s rich same Victorian homes, many of which are now listed in the architectural heritage. Each of our three tours combines a National Register of Historic Places. variety of these and other architectural styles but has a unique flavor all its own. We hope you have fun while walking on these tours that take you to some of our most architecturally historic homes. Some From its beginning, Laramie was a railroad town, and, like are prominently located on busy streets where passing traffic other “Hell-on-Wheels” towns, its early history was violent and rarely slows to admire their splendor; others are wonderful spectacular. Named for a French trapper, Jacques LaRamie, it old gems on quiet neighborhood streets, their outstanding was also one of the few end-of-the-tracks encampments along architectural elements sometimes obscured by century-old trees. the route that survived. -

Frank Lloyd Wright 978-2-86364-338-9 Cinq Approches ISBN / Approches Cinq

frank lloydwright DANIEL TREIBER DANIEL 978-2-86364-338-9 PARENTHÈSES ISBN cinq approches / approches cinq Wright, Lloyd Frank / Treiber Daniel www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com WRIGHT, JUSQU’À NOUS Dans ce nouveau livre que je consacre à Frank Lloyd Wright, je me propose d’aborder son œuvre selon cinq approches différentes. 978-2-86364-338-9 L’essai introductif est une présentation de ensemble de ses travaux à travers une lecture des renver- l’ ISBN / sements opérés par chaque nouvelle « période » par rapport à la précédente. Wright a vécu jusqu’à près de 90 ans et, approches tout au long de sa longue vie, l’architecte américain s’est cinq montré capable de se renouveler d’une manière specta- culaire. Plusieurs « styles » se partagent en effet l’œuvre : Wright, une première période presque Art nouveau, une deuxième Lloyd plus singulière et souvent considérée comme un peu énig- Frank matique, d’une ornementation encore plus foisonnante, / puis, enfin, une période délibérément moderne avec la Treiber production d’icônes de l’architecture, la Maison sur la cascade et le musée Guggenheim. La deuxième approche est consacrée au « côté Daniel Ruskin » de Wright. Le grand historien américain Henry-Russell Hitchcock a déclaré dans son Architecture : XIXe et XXe siècles que ce qui faisait la « profonde diffé- rence » entre Frank Lloyd Wright et Auguste Perret, un autre novateur quasiment de la même génération, était que 7 www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com « l’un avait dans le sang la tradition du néogothique anglais exponentielle de notre environnement, c’est le point par — en bonne part due à ses lectures de Ruskin — tandis lequel les préoccupations de Wright sont étonnamment que l’autre ne l’avait pas ». -

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Frank Lloyd Wright - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Frank_... Frank Lloyd Wright From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Frank Lloyd Wright (born Frank Lincoln Wright, June 8, 1867 – April 9, Frank Lloyd Wright 1959) was an American architect, interior designer, writer and educator, who designed more than 1000 structures and completed 532 works. Wright believed in designing structures which were in harmony with humanity and its environment, a philosophy he called organic architecture. This philosophy was best exemplified by his design for Fallingwater (1935), which has been called "the best all-time work of American architecture".[1] Wright was a leader of the Prairie School movement of architecture and developed the concept of the Usonian home, his unique vision for urban planning in the United States. His work includes original and innovative examples of many different building types, including offices, churches, schools, Born Frank Lincoln Wright skyscrapers, hotels, and museums. Wright June 8, 1867 also designed many of the interior Richland Center, Wisconsin elements of his buildings, such as the furniture and stained glass. Wright Died April 9, 1959 (aged 91) authored 20 books and many articles and Phoenix, Arizona was a popular lecturer in the United Nationality American States and in Europe. His colorful Alma mater University of Wisconsin- personal life often made headlines, most Madison notably for the 1914 fire and murders at his Taliesin studio. Already well known Buildings Fallingwater during his lifetime, Wright was recognized Solomon R. Guggenheim in 1991 by the American Institute of Museum Architects as "the greatest American Johnson Wax Headquarters [1] architect of all time." Taliesin Taliesin West Robie House Contents Imperial Hotel, Tokyo Darwin D.