Sierra Wave by Beth Pratt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources Available from Twin Cities JACL

CLASSROOM RESOURCES ON WORLD WAR II HISTORY AND THE JAPANESE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Available from the Twin Cities chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) (Updated September 2013) *Denotes new to our collection Contact: Sally Sudo, Twin Cities JACL, at [email protected] or (952) 835-7374 (days and evenings) SPEAKERS BUREAU Topics: Internment camps and Japanese American WWII soldiers Volunteer speakers are available to share with students their first-hand experiences in the internment camps and/or as Japanese American soldiers serving in the U.S. Army in the European or Pacific Theaters during World War II. (Note: limited to schools within the Twin Cities metropolitan area.) LIST OF RESOURCES Materials are available on loan for no charge Videocassette Tapes Beyond Barbed Wire - 88 min 1997, Mac and Ava Picture Productions, Monterey, CA Documentary. Personal accounts of the struggles that Japanese Americans faced when they volunteered or were drafted to fight in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II while their families were interned in American concentration camps. The Bracelet - 25 min 2001, UCLA Asian American Studies Center and the Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA Book on video. Presentation of the children’s book by Yoshiko Uchida about two friends separated by war. Second grader Emi is forced to move into an American concentration camp, and in the process she loses a treasured farewell gift from her best friend. Book illustrations are interwoven with rare home movie footage and historic photographs. Following the reading, a veteran teacher conducts a discussion and activities with a second grade class. -

Collection Highlights Since Its Founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts Has Built a Collection of Nearly 5,000 Artworks

Collection Highlights Since its founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts has built a collection of nearly 5,000 artworks. Enjoy an in-depth exploration of a selection of those artworks acquired by gift, bequest, or purchase support by special donors, as written by staff curators and guest editors over the years. Table of Contents KENOJUAK ASHEVAK Kenojuak Ashevak (ken-OH-jew-ack ASH-uh-vac), one of the most well-known Inuit artists, was a pioneering force in modern Inuit art. Ashevak grew up in a semi-nomadic hunting family and made art in various forms in her youth. However, in the 1950s, she began creating prints. In 1964, Ashevak was the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary, Eskimo* Artist: Kenojuak, which brought her and her artwork to Canada’s—and the world’s—attention. Ashevak was also one of the most successful members of the Kinngait Co-operative, also known as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, established in 1959 by James Houston, a Canadian artist and arts administrator, and Kananginak Pootoogook (ka-nang-uh-nak poo-to-guk), an Inuit artist. The purpose of the co-operative is the same as when it was founded—to raise awareness of Inuit art and ensure indigenous artists are compensated appropriately for their work in the Canadian (and global) art market. Ashevak’s signature style typically featured a single animal on a white background. Inspired by the local flora and fauna of the Arctic, Ashevak used bold colors to create dynamic, abstract, and stylized images that are devoid of a setting or fine details. -

November 5, 2009

ATTACHMENT 2 L ANDMARKSLPC 01-07-10 Page 1 of 18 P RESERVATION C OMMISSION Notice of Decision MEETING OF: November 5, 2009 Property Address: 2525 Telegraph Avenue (2512-16 Regent Street) APN: 055-1839-005 Also Known As: Needham/Obata Building Action: Landmark Designation Application Number: LM #09-40000004 Designation Author(s): Donna Graves with Anny Su, John S. English, and Steve Finacom WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of 2525 Telegraph Avenue, the Needham/Obata Building, was initiated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission at its meeting on February 5, 2009; and WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of the Needham/Obata Building is exempt from CEQA pursuant to Section 15061.b.3 (activities that can be seen with certainty to have no significant effect on the environment) of the CEQA Guidelines; and WHEREAS, the Landmarks Preservation Commission opened a public hearing on said proposed landmarking on April 2, 2009, and continued the hearing to May 7, 2009, and then to June 4, 2009; and WHEREAS, during the overall public hearing the Landmarks Preservation Commission took public testimony on the proposed landmarking; and WHEREAS, on June 4, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the subject property is worthy of Landmark status; and WHEREAS, on July 9, 2009, following release of the Notice of Decision (NOD) on June 29, 2009, the property owner Ali Elsami submitted an appeal requesting that the City Council overturn or remand the Landmark decision; and WHEREAS, on September 22, 2009, the City Council considered Staff’s -

Download the Entire Journey Home Curriculum

Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in WWII Arkansas Journey Home Curriculum An interdisciplinary unit for 4th-6th grade students View of the Jerome Relocation Center as seen from the nearby train tracks, June 18, 1944. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, ARC ID 539643, Photographer Charles Mace Kristin Dutcher Mann, Compiler and Editor Ryan Parson, Editor Vicki Gonterman Patricia Luzzi Susan Turner Purvis © 2004, Board of Trustees, University of Arkansas 2 ♦ Life Interrupted: Journey Home Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in World War II Arkansas Life Interrupted is a partnership between the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Public History program and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, Cali- fornia. Our mission is to research the experiences of Japanese Americans in World War II Arkansas and educate the citizens of Arkansas and the nation about the two camps at Jerome and Rohwer. Major funding for Life Interrupted was provided by the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. We share the story of Japanese Americans because we honor our nation’s diversity. We believe in the importance of remembering our history to better guard against the prejudice that threatens liberty and equality in a democratic society. We strive as a metropolitan univer- sity and a world-class museum and to provide a voice for Japanese Americans and a forum that enables all people to explore their own heritage and culture. We promote continual exploration of the meaning and value of ethnicity in our country through programs that preserve individual dignity, strengthen our communities, and increase respect among all people. -

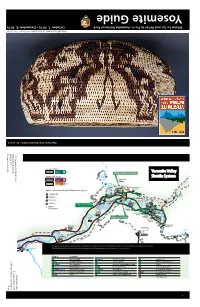

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park October 7, 2015 - December 8, 2015 8, December - 2015 7, October Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where Butterfly basket made by Julia Parker. Parker. Julia by made basket Butterfly NPS Photo / YOSE 50160 YOSE / Photo NPS Volume 40, Issue 8 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Chiura Obata (1885-1975)

Chiura Obata (1885-1975) Teacher Packet ©️2020 1 Table of Contents Biography - Chuira Obata 3 Lesson 1 : Obata Inspired Landscape Art (grades K -12) 3 Lesson 2 : Obata-Inspired Poetry (grades 2 - 7) 7 Lesson 3 : Environmentalism “Can Art Save the World?” (grades 4-8) 10 Lesson 4 : 1906 San Francisco Earthquake (grades 4 and above) 13 Lesson 5 : Japanese Incarceration Experience and Political Art (grades 6-12) 18 Resources 22 2 Biography - Chuira Obata Chiura Obata (1885-1975) was a renowned landscape artist, professor, and devoted environmentalist. Born 1885, in Japan, Obata studied ink painting before immigrating to California in 1903. After settling in Japantown in San Francisco, Obata established himself as an artist and took on large-scale commissioned art projects. After an influential trip to Yosemite in 1928, Obata began devoting his art to portraying landscapes and the beauty of nature. Throughout the next decade, Obata continued to earn recognition, but like many Japanese Americans during WWII, his life was violently uprooted as his family was interned, first at Tanforan and then at Topaz. During his imprisonment, Obata was able to start art schools at both camps, teaching hundreds of students and even holding an exhibition in 1942. After the end of the war, Obata returned to lecture at UC Berkeley, joined the Sierra Club’s environmentalist efforts, and consistently celebrated Japanese aesthetics until his death. Over the course of a seven-decade career, Obata became a prominent educator at UC Berkeley and a central leader in -

Obata As an Artist and a Lover of Nature

er 1993 me 55 ber 3 0 mal for bers of the YoseANte mite Association Janice T. Driesbach pact on Obata as an artist and a lover of nature. Chiura Obata B (1885-1975), a In Obata's words, that 1927 Japanese-born artist who spent Yosemite trip "was the greatest most of his adult life in the harvest for my whole life and San Francisco Bay Area, is future in painting. The expres- little-known for his Yosemite- sion from Great Nature is im- inspired work. But Obata, who measurable"' The classically- immigrated to California in trained sumi artist appears to 1903, produced a number of have arrived in the Sierra with A remarkable paintings, sketches a mission; he was determined and woodblock prints of the to record the wondrous land- Yosemite region from the time scapes of Tuolumne Meadows, of his first visit to the park in Mount Lyell, Mono Lake, and 1927 through the rest of his life. the rest of Yosemite's high That initial visit, which lasted country in pencil, sumi, and six weeks, had a profound im- watercolor. The sculptor T FACE. TWO Cover: Allorrriug at Mono Lake, 19 Color woodblock print, 11 x 151' Buck Meadow, June 17, 1927. Su on postcard, 3Y x 5% in. How Old Is the Moon, July 2, 19 Sumi on postcard, 5'U x 3'S in. Robert Boardman Howard, this abundant, great nature, t who accompanied Obata leave here would mean losin during a portion of the trip, great opportunity that come observed, "Every pause for only once in a thousand year rest saw Chiura at work. -

The Tanforan Memorial Project: How Art and History Intersected

THE TANFORAN MEMORIAL PROJECT: HOW ART AND HISTORY INTERSECTED A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University AS In partial fulfillment of 5 0 the requirements for the Degree AOR- • 033 Master of Arts in Humanities by Richard J. Oba San Francisco, California Fall Term 2017 Copyright by Richard J. Oba 2017 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read “The Tanforan Memorial Project: How Art and History Intersected” by Richard J. Oba, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Humanities at San Francisco State University. I Saul Steier, Associate Professor, Humanities “The Tanforan Memorial Project: How Art and History Intersected” Richard J. Oba San Francisco 2017 ABSTRACT Many Japanese Americans realize that their incarceration during WWII was unjust and patently unconstitutional. But many other American citizens are often unfamiliar with this dark chapter of American history. The work of great visual artists like Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Chiura Obata, Mine Okubo, and others, who bore witness to these events convey their horror with great immediacy and human compassion. Their work allows the American society to visualize how the Japanese Americans were denied their constitutional rights in the name of national security. Without their visual images, the chronicling of this historical event would have faded into obscurity. I certify that the Abstract is a correct representation of the content of this Thesis ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to acknowledge the support and love of my wife, Sidney Suzanne Pucek, May 16, 1948- October 16, 2016. -

Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A

From La Farge to Paik Research Resources at the Smithsonian American Art Museum Amelia A. Goerlitz A wealth of materials related to artistic interchange between the United States and Asia await scholarly attention at the Smithsonian Institution.1 The Smithsonian American Art Museum in particular owns a remarkable number of artworks that speak to the continuous exchange between East and West. Many of these demonstrate U.S. fascination with Asia and its cultures: prints and paintings of America’s Chinatowns; late-nineteenth- century examples of Orientalism and Japonisme; Asian decorative arts and artifacts donated by an American collector; works by Anglo artists who trav- eled to Asia and India to depict their landscapes and peoples or to study traditional printmaking techniques; and post-war paintings that engage with Asian spirituality and calligraphic traditions. The museum also owns hundreds of works by artists of Asian descent, some well known, but many whose careers are just now being rediscovered. This essay offers a selected overview of related objects in the collection. West Looks East American artists have long looked eastward—not only to Europe but also to Asia and India—for subject matter and aesthetic inspiration. They did not al- ways have to look far. In fact, the earliest of such works in the American Art Mu- seum’s collection consider with curiosity, and sometimes animosity, the presence of Asians in the United States. An example is Winslow Homer’s engraving enti- tled The Chinese in New York—Scene in a Baxter Street Club-House, which was produced for Harper’s Weekly in 1874. -

Santa Clara Magazine, Volume 48 Number 4, Spring 2007 Santa Clara University

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Santa Clara Magazine SCU Publications Spring 2007 Santa Clara Magazine, Volume 48 Number 4, Spring 2007 Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/sc_mag Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Business Commons, Education Commons, Engineering Commons, Law Commons, Life Sciences Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Santa Clara University, "Santa Clara Magazine, Volume 48 Number 4, Spring 2007" (2007). Santa Clara Magazine. 9. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/sc_mag/9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the SCU Publications at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Magazine by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V OLUME 48 N UMBER 4 What’s wrong Magazine with this picture? That was the question pho- tographer and SCU student Leyna Roget asked. The answer: Robert Romero, the boy holding the camera, and his family, are homeless. SantaPublished for the Alumni and Friends of SantaClara Clara University Spring 2007 The photos were taken during a Free Portrait Day that SCU students set up at Community Homeless Alliance Ministry in down- town San Jose in November. Solving mental It was part of photography instructor Renee Billingslea’s health challenges for course in Exploring Society through Photography. a new millennium Read the story and see more photos online at Page 12 www.santaclaramagazine.com. Parting Shot PHOTO: LEYNA ROGET LEYNA PHOTO: Parents of SCU grads: Has your son or daughter moved? E-mail us at [email protected] with their updated addresses so they’ll be sure to continue receiving this magazine. -

Lives and Legacy by Joyce Nao Takahashi

Japanese American Alumnae of the University of California, Berkeley: Lives and Legacy Joyce Nao Takahashi A Project of the Japanese American Women/Alumnae of the University of California, Berkeley Front photo: 1926 Commencement, University of California, Berkeley. Photo Courtesy of Joyce N. Takahashi Copyright © 2013 by Joyce Nao Takahashi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Preface and Acknowledgements I undertook the writing of the article, Japanese American Alumnae: Their Lives and Legacy in 2010 when the editors of the Chronicle of the University of California, Carroll Brentano, Ann Lage and Kathryn M. Neal were planning their Issue on Student Life. They contacted me because they wanted to include an article on Japanese American alumnae and they knew that the Japanese American Women/Alumnae of UC Berkeley (JAWAUCB), a California Alumni club, was conducting oral histories of many of our members, in an attempt to piece together our evolution from the Japanese Women’s Student Club (JWSC). As the daughter of one of the founders of the original JWSC, I agreed to research and to write the JWSC/JAWAUCB story. I completed the article in 2010, but the publication of the Chronicle of the University of California’s issue on Student Life has suffered unfortunate delays. Because I wanted to distribute our story while it was still timely, I am printing a limited number of copies of the article in a book form I would like to thank fellow JAWAUCB board members, who provided encouragement, especially during 2010, Mary (Nakata) Tomita, oral history chair, May (Omura) Hirose, historian, and Irene (Suzuki) Tekawa, chair. -

Berkeley Book Shelf [ Supplied by Stephen E

Berkeley Book Shelf [ Supplied by Stephen E. Barton ] Adler, Margot; Heretic’s Heart: A Journey Through Spirit and Revolution; Beacon Press, Boston, 1997 Adler, Patricia and five others (editors); Fire in the Hills: a Collective Remembrance; Berkeley, 1992 Anderson, Douglas Firth; “An Active and Unceasing Campaign of Social Education: J. Stitt Wilson and Herronite Socialist Christianity” in Jacob H. Dorn, editor, Socialism and Christianity in early 20th century America, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998. Anderson, Douglas Firth; "The Reverend J. Stitt Wilson and Christian Socialism in California." In Religion and Society in the American West, eds. Carl Guarneri and David Alvarez. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1987. Appleyard, Donald; Livable Streets; (Ch. 12. “Berkeley at the Barricades”), University of California Press, Berkeley, 1981 Aptheker, Bettina F.; Intimate Politics: How I Grew Up Red, Fought for Free Speech, and Became a Feminist Rebel; Seal Press, Emeryville, 2006 Barish, Mildred S.; Tamalpais Tales: A Berkeley Neighborhood Remembers; Buckeye Books, Berkeley, 2004 Stephen E. Barton, “From Community Control to Professionalism: Social Housing in Berkeley, California, 1976 – 2011”, Journal of Planning History, forthcoming. (on-line publication May 2013) Stephen E. Barton, “The City’s Wealth and the City’s Limits: Progressive Housing Policy in Berkeley, California, 1976 – 2011”, Journal of Planning History, May 2012, 11:2, 160-178. Barton, Stephen E.; “The Success and Failure of Strong Rent Control in the City of Berkeley, 1978 - 1995”, pp. 88-109 in W. Dennis Keating, Michael Teitz and Andrejs Skaburskis eds. Rent Control: Regulation and the Rental Housing Market, Center for Urban Policy Research, 1998.