Japan's Early Ambassadors to San Francisco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loma Rica Ranch Report (PDF)

.... HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT FEATURES OF THE LOMA RICA RANCH, GRASS VALLEY, CALIFORNIA Compiled and Written by Deb Haas TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction iii. Topographical Map of Lorna Rica Ranch v. The Southern .Maidu 1 • McCarty/Lorna Rica Ranch 3. Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad. 5. Idaho Maryland Mine • 6. Errol MacBoyle B. MacBoyle Lake & The World's Fair Fountain 11 • Miscellaneous Information • 1 2. Recommendations 1 3. Appendixes • 15. Endnotes 33. Bibliography 35. ii. Introduction In May 1992, Teachers Management Investment Corporation requested that the Nevada County Historical Landmarks Commission attempt to identify and research the historically significant points of interest located on the Lorna Rica Ranch. NCHLC conducted searches of county records, newspapers, Nevada County Historical Society Bulletins from 1948 to the present, reviewed pertinent literature and histories, searched the Empire Mine files and conducted interviews of citizens in attempts to determine the historical points of interest on Lorna Rica Ranch. Additionally, field surveys were conducted by members of the NCHLC to better understand the various facets of the potential sites located on Lorna Rica Ranch. This enables the NCHLC to develop a clearer understanding of what could be considered historically significant to the citizens of Nevada County. The research uncovered five historically significant tangible sites. The sections under investigation are: (1) two prehistoric Southern Maidu sites; (2) remnants of the Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad beds; (3) remains of the Idaho Maryland mine operations; (4) the Lorna Rica Ranch Thoroughbred operations; and (5) the MacBoyle reservoir which includes the purported World's Fair Fountain. The individual, Errol MacBoyle is an historically significant individual that by all rights should be included in the historically significant list of the Lorna Rica Ranch. -

Curriculum Vitae

H A I N E S G A L L E R Y PATSY KREBS b. 1940 Lives and works in Inverness, CA EDUCATION 1977 MFA, Claremont Graduate School, Claremont, CA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Aletheia: reveal/conceal, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA Focus: Patsy Krebs, Bolinas Museum, CA 2017 Patsy Krebs: Paintings, 15th Street Gallery, Boulder, CO Recent Paintings, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2015 Patsy Krebs: Time Passages, Michael Warren Contemporary, Denver, CO 2013 Parable of the Oxherder: Aquatint Etchings, Lora Schlesinger Gallery, Santa Monica, CA Fugue, Steamboat Springs Arts Council, Steamboat Springs, CO 2012 New Paintings, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2011 The Oxherder Parable, Page Bond Gallery, Richmond, VA 2009 Selected Paintings, San Marco Gallery, Dominican University of California, San Rafael, CA 2008 Selected Paintings 1980 - 2000, Sandy Carson Gallery, Denver, CO Hibernal Dreams, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2007 Rising, Hunsaker/Schlesinger Fine Art, Santa Monica, CA 2006 Works on Paper, Hunsaker/Schlesinger Fine Art, Santa Monica, CA 2005 New Works, Sandy Carson Gallery, Denver, CO A Decade, Flora Lamson Hewlett Library, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA 2004 Portfolio: Watercolor Suites, Interchurch Center Galleries, New York, NY New Work, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2002 New Minimalism, Aalto Space, Ashland, OR 2001 Elysion, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle, WA 1999 Ovum, Haines Gallery, San Francisco, CA 1997 Gensler and Associates, San Francisco, CA 1996 Painting, Haines Gallery, -

San Francisco Examiner September 22, 1889

The Archive of American Journalism Ambrose Bierce Collection San Francisco Examiner September 22, 1889 Prattle A Record of Individual Opinion It is stated that the furniture for the new cruiser Charleston “would grace a palace.” Mention is made of “magnificent sideboards with elaborate carvings and panels and fine mirrors,” “great heavy mahogany tables and desks of elaborate design and finish, and upholstered chairs by the score.” The cabins and staterooms, it is added, have sides “composed of panels of polished sycamore and teak, each of which is a gem of the cabinet-maker’s art.” It is to be hoped that the officers and sailors of the Charleston will harmonize with the beautiful environment. An Admiral out of keeping with the elaborate carvings, a midshipman who should not match the panels of polished sycamore, or an able seaman unable to subdue his complexion to the exact shade of the mahogany tables, would precipitate a grave artistic disaster-at-sea. If the vessel’s gunpowder is suitably perfumed with attar-of-roses, her guns gold-lated and operated by crews in silk attire, captained by Professors of Deportment, the national honor may be considered safe until there shall be a war. If our “new Navy” had no graver virtues, no more perilous perfections than gorgeous furniture, it would be well for us; but )in my humble judgment) we have not, and are not likely soon to have, a single war vessel that is worth the cost of its rudder. Our safety is to be found in the fact that the war vessels of other nations are no better. -

Mayor Angelo Rossi's Embrace of New Deal Style

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Trickle-down paternalism : Mayor Angelo Rossi's embrace of New Deal style Ronald R. Rossi San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Rossi, Ronald R., "Trickle-down paternalism : Mayor Angelo Rossi's embrace of New Deal style" (2009). Master's Theses. 3672. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.5e5x-9jbk https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3672 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRICKLE-DOWN PATERNALISM: MAYOR ANGELO ROSSI'S EMBRACE OF NEW DEAL STYLE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Ronald R. Rossi May 2009 UMI Number: 1470957 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 1470957 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. -

Collection Highlights Since Its Founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts Has Built a Collection of Nearly 5,000 Artworks

Collection Highlights Since its founding in 1924, the Kalamazoo Institute of Arts has built a collection of nearly 5,000 artworks. Enjoy an in-depth exploration of a selection of those artworks acquired by gift, bequest, or purchase support by special donors, as written by staff curators and guest editors over the years. Table of Contents KENOJUAK ASHEVAK Kenojuak Ashevak (ken-OH-jew-ack ASH-uh-vac), one of the most well-known Inuit artists, was a pioneering force in modern Inuit art. Ashevak grew up in a semi-nomadic hunting family and made art in various forms in her youth. However, in the 1950s, she began creating prints. In 1964, Ashevak was the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary, Eskimo* Artist: Kenojuak, which brought her and her artwork to Canada’s—and the world’s—attention. Ashevak was also one of the most successful members of the Kinngait Co-operative, also known as the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, established in 1959 by James Houston, a Canadian artist and arts administrator, and Kananginak Pootoogook (ka-nang-uh-nak poo-to-guk), an Inuit artist. The purpose of the co-operative is the same as when it was founded—to raise awareness of Inuit art and ensure indigenous artists are compensated appropriately for their work in the Canadian (and global) art market. Ashevak’s signature style typically featured a single animal on a white background. Inspired by the local flora and fauna of the Arctic, Ashevak used bold colors to create dynamic, abstract, and stylized images that are devoid of a setting or fine details. -

The San Francisco Bay Area, California

The San Francisco Bay Area, Can disaster be a good thing for the arts? In the California San Francisco Bay Area, the answer is a qualified “yes.” A terrible earthquake has shaken loose mil- lions of dollars for the arts, while urban sprawl has boosted the development of arts centers right in the communities where people live. After the Loma Prieta earthquake struck in 1989, many key institutions were declared unsafe and had to be closed, fixed and primped. Here’s what reopened in the past five years alone: American Conservatory Theatre (ACT), the city’s major repertory theater, for $27 million; the War Memorial Opera House, home of the San Francisco Opera and Ballet, for $88 million; and on the fine arts front, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, for $40 million; and the Cantor Center for the Visual Arts at Stanford University, for $37 million. Another $130 million is being raised to rebuild the seismically crippled M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, and at least $30 million is being sought to repair the Berkeley Art Museum. Within San Francisco itself, a vital visual arts center has been forged just within the last five years with the opening of the new $62 million San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. Meanwhile the Jewish Museum, the Asian Art Museum, the Mexican Museum and a new African-American cultural center all plan to move to seismically safe buildings in the area in the next two years. Art galleries, on the other hand, limp along compared with those in Los Angeles or New York. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

November 5, 2009

ATTACHMENT 2 L ANDMARKSLPC 01-07-10 Page 1 of 18 P RESERVATION C OMMISSION Notice of Decision MEETING OF: November 5, 2009 Property Address: 2525 Telegraph Avenue (2512-16 Regent Street) APN: 055-1839-005 Also Known As: Needham/Obata Building Action: Landmark Designation Application Number: LM #09-40000004 Designation Author(s): Donna Graves with Anny Su, John S. English, and Steve Finacom WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of 2525 Telegraph Avenue, the Needham/Obata Building, was initiated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission at its meeting on February 5, 2009; and WHEREAS, the proposed landmarking of the Needham/Obata Building is exempt from CEQA pursuant to Section 15061.b.3 (activities that can be seen with certainty to have no significant effect on the environment) of the CEQA Guidelines; and WHEREAS, the Landmarks Preservation Commission opened a public hearing on said proposed landmarking on April 2, 2009, and continued the hearing to May 7, 2009, and then to June 4, 2009; and WHEREAS, during the overall public hearing the Landmarks Preservation Commission took public testimony on the proposed landmarking; and WHEREAS, on June 4, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission determined that the subject property is worthy of Landmark status; and WHEREAS, on July 9, 2009, following release of the Notice of Decision (NOD) on June 29, 2009, the property owner Ali Elsami submitted an appeal requesting that the City Council overturn or remand the Landmark decision; and WHEREAS, on September 22, 2009, the City Council considered Staff’s -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

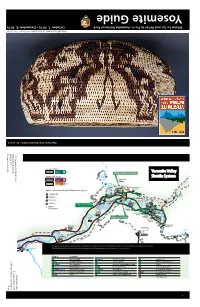

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park October 7, 2015 - December 8, 2015 8, December - 2015 7, October Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where Butterfly basket made by Julia Parker. Parker. Julia by made basket Butterfly NPS Photo / YOSE 50160 YOSE / Photo NPS Volume 40, Issue 8 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

The Orkustra

THE ORKUSTRA This day-by-day diary of The Orkustra's live, studio, broadcasting and private activities is the result of two decades of research and interview work by Bruno Ceriotti, but without the significant contributions by other kindred spirits this diary would not have been possible. So, I would like to thank all the people who, in one form or another, contributed to this timeline: Jaime Leopold (RIP), Bobby Beausoleil, David LaFlamme, Henry Rasof, Nathan Zakheim, Stephen Hannah, Jesse Barish, Steve LaRosa, Rod Harper (RIP), Colin Hill, Ross Hannan, Corry Arnold, William Hjortsberg, Aldo Pedron, Klemen Breznikar, Reg E. Williams, Charles Perry, Penny DeVries, Claire Hamilton, Lessley Anderson, Ralph J. Gleason (RIP), Craig Fenton, Alec Palao, Johnny Echols, 'Cousin Robert' Resner, Roman Garcia Albertos, James Marshall, Chester Kessler, Gene Anthony, Christopher Newton, Loren Means, The San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco Chronicle, San Francisco Oracle, and Berkeley Barb. September 1966 Undoubtedly the most experimental and ecletically diverse band of the so-called 'San Francisco Sound', The Orkustra were put together by the infamous Bobby Beausoleil. A larger than life character with a mixed reputation ("He was like Bugs Bunny," says Orkustra's bandmate Nathan Zakheim. "Very in your face, enthuastic."), Robert Kenneth Beausoleil, aka 'Cupid', aka 'Bummer Bob', aka 'Bobby Snofox', was born on Thursday, November 6, 1947, in Santa Barbara, California. After dropping out of high school and let his hair grow out, Bobby moved to Los Angeles in search of fame and fortune in 1965. There, over the summer, he played a six-string rhythm guitar with The Grass Roots, a folk- rock band later known as LOVE, for only three weeks, and also made a cameo appearance (as 'Cupid') in the famous underground documentary movie Mondo Hollywood. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Friday, May 15, 2015 Contact: J. David Kennedy Oahu Publications, Inc. (808) 529-4810 David Lato Communications Pacific (808) 543-3581 [email protected] OAHU PUBLICATIONS, INC. APPOINTS AARON J. KOTAREK VICE PRESIDENT OF CIRCULATION Kotarek Brings Multi-Channel Expertise as a Publishing Leader HONOLULU – Oahu Publications, Inc. (OPI) today announced that Aaron J. Kotarek has joined the firm as vice president of circulation. He will be responsible for creating innovative programs, improving delivery metrics and enhancing customer service with a goal of overall readership growth, revenue enhancement, digital platform engagement and maximizing distribution/transportation logistics for Oahu Publications’ entire Hawaii-based print and digital product portfolio. In addition to overseeing circulation duties at OPI’s four daily print publications: the Honolulu Star-Advertiser on Oahu, The Garden Island on Kauai, West Hawaii Today and the Hawaii Tribune- Herald on the island of Hawaii, Kotarek also will oversee circulation for OPI’s weekly publications, monthly magazines, niche websites, mobile apps and social media channels. (more) Oahu Publications, Inc. Appoints Aaron J. Kotarek Vice President of Circulation Page 2 “After a nationwide search that included many talented and experienced candidates, we are pleased that Aaron has agreed to join our senior management team,” said Dennis Francis, OPI president and publisher of the Star-Advertiser. “Aaron's experience is deep in both print marketing and digital platforms. The Honolulu Star-Advertiser is now among the most successful and elite newspapers in the United States, which has enabled us to attract top candidates from Hawaii and across the nation to fill our key positions.