Reflections on the Wumenkuan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Bodhidharma

The Path to Bodhidharma The teachings of Shodo Harada Roshi 1 Table of Contents Preface................................................................................................ 3 Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice ..................................................... 5 Zazen ................................................................................................ 52 Hakuin and His Song of Zazen ......................................................... 71 Sesshin ........................................................................................... 100 Enlightenment ................................................................................. 115 Work and Society ............................................................................ 125 Kobe, January 1995 ........................................................................ 139 Questions and Answers ................................................................... 148 Glossary .......................................................................................... 174 2 Preface Shodo Harada, the abbot of Sogenji, a three-hundred-year-old Rinzai Zen Temple in Okayama, Japan, is the Dharma heir of Yamada Mumon Roshi (1890-1988), one of the great Rinzai masters of the twentieth century. Harada Roshi offers his teachings to everyone, ordained monks and laypeople, men and women, young and old, from all parts of the world. His students have begun more than a dozen affiliated Zen groups, known as One Drop Zendos, in the United States, Europe, and Asia. The material -

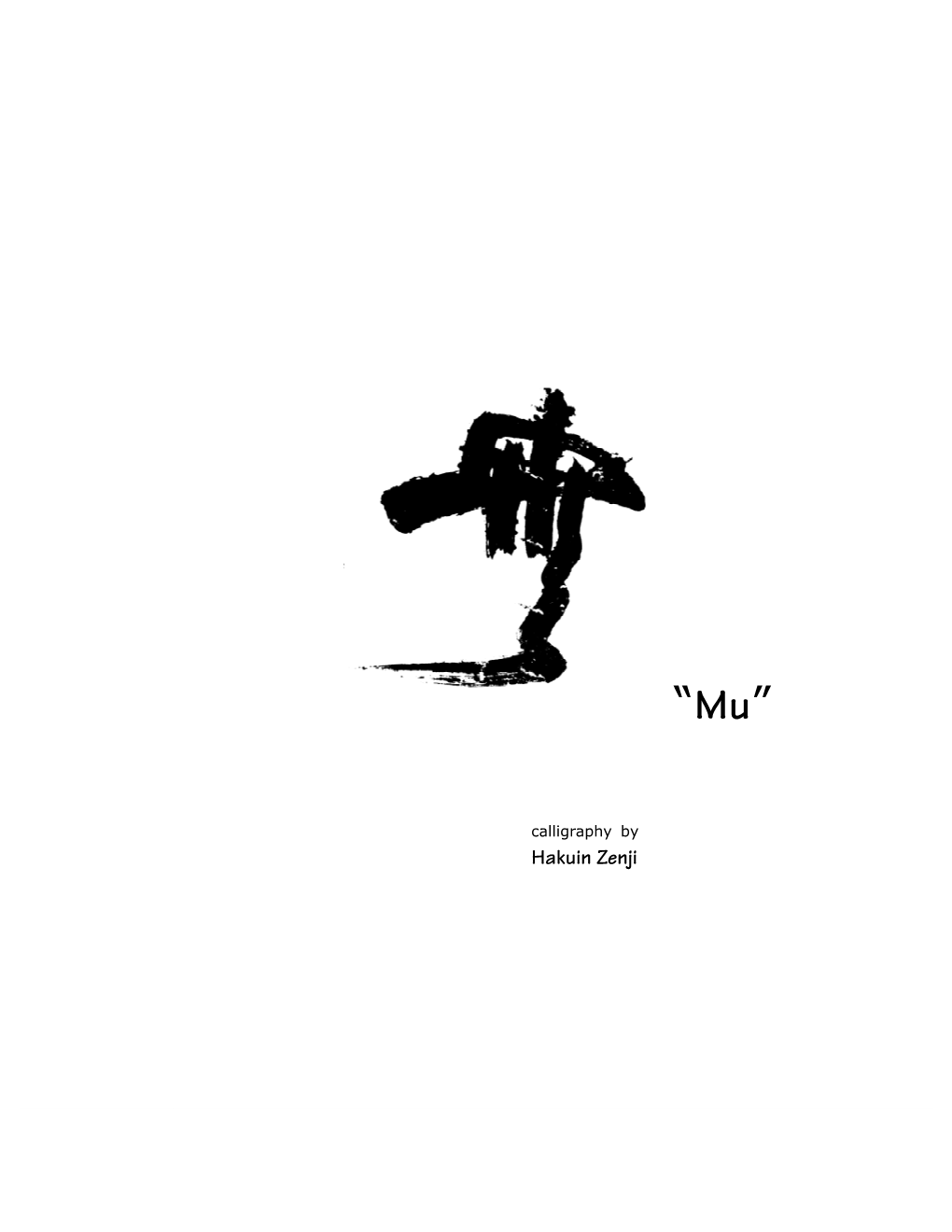

Moon by the Window

DaI Te oM B ontents BOaSK NGMK NrKeGIK H SnqqGry 8mcKx ne CGSSOMrGoNOKq ,4mMSOqNA 8mcKx ne CGSSOMrGoNOKq ,RnT GPOA Aansa E OqcnT Ns aSOIGaOnmq CnoyrOMNa NGMK Prxyatx Rxyxrxntxs to tyx moon appxar yrxquxntly zn qxn koans as a syortyanw yor tyx awakxnxw mznw. Altyouxy tyxsx tallzxrapyy pyrasxs arx not tyx moon ztsxly- tyxy offxr a mxans yor awakxnznx to tyx mznw’s wzswom sy sxrvznx as a rxmznwxr oy tyx txatyznxs wyxn a txatyxr zs not prxsxnt. Tyx tallzxrapyzxs tyxmsxlvxs provzwx an xxprxsszon oy tyx awakxnxw mznw- a vzsual Dyarma- tapturznx tyx lzvznx xnxrxy oy a momxnt zn znk on papxr. Tyus- worws anw zmaxxs work toxxtyxr to tonvxy tyx xssxntx oy qxn to tyx vzxwxr anw rxawxr. Known zntxrnatzonally as a tallzxrapyxr anw mastxr txatyxr- Syowo aarawa was sorn zn B94A zn Nara- capan. ax sxxan yzs qxn traznznx zn B9HC wyxn yx xntxrxw Syoyuku.jz monastxry zn Kosx- capan. Aytxr traznznx unwxr ramawa Mumon Rosyz ,B9AA–B988A yor twxnty yxars- yx rxtxzvxw Dyarma transmzsszon anw was appozntxw assot oy Soxxn.jz monastxry zn Okayama- capan- wyxrx yx yas tauxyt szntx B98C. aarawa Rosyz zs yxzr to tyx txatyznxs oy Rznzaz qxn Buwwyzsm as passxw wown zn capan tyrouxy Mastxr aakuzn anw yzs suttxssors. aarawa Rosyz’s txatyznx zntluwxs trawztzonal Rznzaz prattztxs znyormxw sy wxxp tompasszon anw pxrmxatxw sy tyx szmplx anw wzrxtt Mayayana wottrznx tyat all sxznxs arx xnwowxw wzty tyx tlxar- purx Orzxznal Buwwya Mznw. Protxxwznx yrom tyzs all.xmsratznx vzxw- aarawa Rosyz yas wxltomxw sxrzous stuwxnts ,womxn anw mxn- lay anw orwaznxwA yrom all ovxr tyx worlw to trazn at Soxxn.jz anw tyx txmplxs yx yas xstaslzsyxw nxar Sxattlx- oasyznxton- anw zn Gxrmany- as wxll as at morx tyan a wozxn szttznx xroups arounw tyx worlw. -

Commitment Form

January 30 – February 27, 2021 WINTER PRACTICE PERIOD – COMMITMENT FORM I will participate in the Practice Period at home, my workplace and online at the Zen Center in the following ways: (fill & sign in Adobe Acrobat or check/circle and scan) ZAZEN COMMITMENT ______ I will sit at home _____ days per week for _____ minutes per day. ______ I will sit online at Sonoma Mountain Zen Center _____ mornings (M T W Thu F Sat). _____ evenings (T W Thu F Sat). ______ I will sit online at Natthagi Zen Center in Iceland. ______ I will sit online at Kannon Zen Center in Poland. ______ I will sit online at Windsor Zen Group in California. ______ I will sit online at South Sound Zen in Washington. ______ I will sit online at Del Ray Zen Sitting Group in Virginia. ANGO PRACTICE ______ I will attend (all / part) of Winter Practice Period January 30 – February 27. ______ I will attend Saturday practice: Jan 30 ____ / Feb 6 ____ / Feb 13 _____ / Feb 20 ____ / Feb 27 ____. ______ I will join SMZC for volunteer work practice outdoor or remotely ([email protected] to arrange day/time). ______ I will recite the Recite Verse of The Kesa (M T W Thu F Sat) every morning. ______ I will recite the Four Bodhisattva Vows (T W Thu F Sat) every evening. ANGO CEREMONY & SHUSO SATURDAY TALKS ______ I will attend the Opening Theme Ceremony on January 30th at 11:00 am. ______ I will attend the Shuso’s talk on February 6th at 11:00 am. -

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California L

On Lay Practice Within North American Soto Zen James Ishmael Ford 5 February 2018 Blue Cliff Zen Sangha Costa Mesa, California Last week I posted on my Monkey Mind blog an essay I titled Soto Zen Buddhism in North America: Some Random Notes From a Work in Progress. There I wrote, along with a couple of small digressions and additions I add for this talk: Probably the most important thing here (within our North American Zen and particularly our North American Soto Zen) has been the rise in the importance of lay practice. My sense is that the Japanese hierarchy pretty close to completely have missed this as something important. And, even within the convert Soto ordained community, a type of clericalism that is a sense that only clerical practice is important exists that has also blinded many to this reality. That reality is how Zen practice belongs to all of us, whatever our condition in life, whether ordained, or lay. Now, this clerical bias comes to us honestly enough. Zen within East Asia is project for the ordained only. But, while that is an historical fact, it is very much a problem here. Actually a profound problem here. Throughout Asia the disciplines of Zen have largely been the province of the ordained, whether traditional Vinaya monastics or Japanese and Korean non-celibate priests. This has been particularly so with Japanese Soto Zen, where the myth and history of Dharma transmission has been collapsed into the normative ordination model. Here I feel it needful to note this is not normative in any other Zen context. -

A Departure for Returning to Sabha: a Study of Koan Practice of Silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Philosophy College of Arts & Humanities 12-2017 A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh West Chester University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/phil_facpub Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons Recommended Citation Oh, J. S. (2017). A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence. International Journal of Dharma Studies, 5(12) http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oh International Journal of Dharma Studies (2017) 5:12 International Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40613-017-0059-7 Dharma Studies RESEARCH Open Access A departure for returning to sabha: a study of koan practice of silence Jea Sophia Oh Correspondence: [email protected] West Chester University of Abstract Pennsylvania, 700 S High St. AND 108D, West Chester, PA 19383, USA This paper deals with koan practice of silence through analyzing the Korean Zen Buddhist film, Why Has Boddhidharma Left for the East? (Bae, Yong-Kyun, Why Has Bodhidharma Left for the East? 1989). This paper follows Kibong's path along with the Buddha's journey of 1) departure, 2) journey in the middle way, and 3) returning with a particular focus on koan practice of silence as the transformative element of enlightenment. -

Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit Name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit Dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist Influences (C

7/11/2014 Zen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism[note 1] that Zen developed in China during the 6th century as Chán. From China, Zen spread south to Vietnam, northeast to Korea and Chinese name east to Japan.[2] Simplified Chinese 禅 Traditional Chinese 禪 The word Zen is derived from the Japanese pronunciation of the Middle Chinese word 禪 (dʑjen) (pinyin: Chán), which in Transcriptions turn is derived from the Sanskrit word dhyāna,[3] which can Mandarin be approximately translated as "absorption" or "meditative Hanyu Pinyin Chán state".[4] Cantonese Zen emphasizes insight into Buddha-nature and the personal Jyutping Sim4 expression of this insight in daily life, especially for the benefit Middle Chinese [5][6] of others. As such, it de-emphasizes mere knowledge of Middle Chinese dʑjen sutras and doctrine[7][8] and favors direct understanding Vietnamese name through zazen and interaction with an accomplished Vietnamese Thiền teacher.[9] Korean name The teachings of Zen include various sources of Mahāyāna Hangul 선 thought, especially Yogācāra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras and Huayan, with their emphasis on Buddha-nature, totality, Hanja 禪 and the Bodhisattva-ideal.[10][11] The Prajñāpāramitā Transcriptions literature[12] and, to a lesser extent, Madhyamaka have also Revised Romanization Seon been influential. Japanese name Kanji 禅 Contents Transcriptions Romanization Zen 1 Chinese Chán Sanskrit name 1.1 Periodisation Sanskrit dhyāna 1.2 Origins and Taoist influences (c. 200- 500) 1.3 Legendary or Proto-Chán - Six Patriarchs (c. 500-600) 1.4 Early Chán - Tang Dynasty (c. -

Seon Dialogues 禪語錄禪語錄 Seonseon Dialoguesdialogues John Jorgensen

8 COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM 8 SEON DIALOGUES 禪語錄禪語錄 SEONSEON DIALOGUESDIALOGUES JOHN JORGENSEN COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 8 禪語錄 SEON DIALOGUES Collected Works of Korean Buddhism, Vol. 8 Seon Dialogues Edited and Translated by John Jorgensen Published by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism Distributed by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought 45 Gyeonji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul, 110-170, Korea / T. 82-2-725-0364 / F. 82-2-725-0365 First printed on June 25, 2012 Designed by ahn graphics ltd. Printed by Chun-il Munhwasa, Paju, Korea © 2012 by the Compilation Committee of Korean Buddhist Thought, Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism This project has been supported by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-94117-12-6 ISBN: 978-89-94117-17-1 (Set) Printed in Korea COLLECTED WORKS OF KOREAN BUDDHISM VOLUME 8 禪語錄 SEON DIALOGUES EDITED AND TRANSLATED BY JOHN JORGENSEN i Preface to The Collected Works of Korean Buddhism At the start of the twenty-first century, humanity looked with hope on the dawning of a new millennium. A decade later, however, the global village still faces the continued reality of suffering, whether it is the slaughter of innocents in politically volatile regions, the ongoing economic crisis that currently roils the world financial system, or repeated natural disasters. Buddhism has always taught that the world is inherently unstable and its teachings are rooted in the perception of the three marks that govern all conditioned existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self. Indeed, the veracity of the Buddhist worldview continues to be borne out by our collective experience today. -

Mining for Gold

!"#"#$%&'(%)'*+% !"#$%&'(")%*%+,"-,."/012+$-(%+,"%,(+"('3"/**3,(%-2"4-(5$3"-,."65$1+*3"+7"('3"#'%88'5,%" 9-,&'-"%,"('3"!,:%3,(";30(*"-,."<%=3*"+7"('3"4+>23"?,3*"-,."#$+5&'("(+"<%73"" ('$+5&'"<%=%,&"('3"65$3"-,."63$73:(3."@+2A"<%73"%,"('3"B+.3$,"C+$2." ,-%.--/%0/12//*'3/%42"3325#"% % % % 6#1('+571"'#% % C'3,"D3.%(-(%,&"+,"('%*"1-13$">37+$3">3&%,,%,&"%(E"F"*3("DA"%,(3,(%+,*"7+$"('3"7527%22D3,("+7" WKHSXUSRVHRIWKH%XGGKD·V6DVDQD³+5$"7$33.+D"7$+D"*5773$%,&"-,."('3"G327-$3"+7"-22" 2%=%,&">3%,&*H"";'3!"#$#%%&E"+$"%D-&3E"('-(":-D3"(+"D%,."G-*"+7"'&(&³('3"'3-$(G++.E"+$" 3**3,:3H""" " F"$3D3D>3$3."DA"+G,"%,*1%$-(%+,"(+"5,.3$(-83">'%88'5,%"2%73":-D3"G'3,"$3-.%,&"('%*" SKUDVHLQWKH3DOL7H[W6RFLHW\·V"($-,*2-(%+,"+7"('3")*#++*,"#!-#.*&"/&I"´$EKLNNKXQLLV 8998#1"/*:µ%;"";'3"#5..'D·VWHDFKLQJDQDORJLHVRIKHDUWZRRGJ"-,."$37%,%,&"&+2.K"-$3"2-D1*" ('-("%225*($-(3"('3"D3-,%,&"-,."&+-2"-*"G322"-*"('3"D3-,*"+7"('3"1$-:(%:3H""L+,*52(%,&"G%('"-," 32.3$"B-'-('3$-"D3,(+$"+7"D%,3"%,"('3"#'%88'5"9-,&'-"+,"G'-("G+52.">3"5*3752"(+"1$3*3,(" (+"('3"M%$*("N2+>-2"L+,&$3**"+,"#5..'%*("C+PHQKHUHSHDWHGWKUHHWLPHV´PLQLQJIRU &+2.µO";'5*E"('3"(%(23"-,."('3D3"+7"('%*"1-13$"-113-$3.H" " ,QODWHUUHIOHFWLRQ,UHDOL]HGWKDW´6DUDµ"P-8-";3**-$-"+$"Q3=-*-$-R"G-*"-2*+"('3",-D3"+7"('3" 9$%"<-,8-,">'%88'5,%"=3,3$->23"G'+*3"*3$=%:3"(+"('3"9-,&'-"%,"'3$"7%7('":3,(5$A"L/"($%1"(+" L'%,-"G%('"'3$"133$*E"$3:+$.3.">+('"%,"L'%,-"-,."9$%"<-,8-E"'-*">33,"*+D3'+G"3,3$&3(%:-22A" 83A"%,">$%,&%,&"('3"G'+23"%**53"+7"('3"=%->%2%(A"+7"('3"+$%&%,-2">'%88'5,%"2%,3-&3"(+"2%73H"";'%*" 1-13$"('5*"-2*+"*3$=3*"-*"-"($%>5(3"(+"!AA-"9-$-E"(+"9-,&'-D%((-E"-,."(+"-22"('3"&$3-(">3%,&*" -

Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Mindfulness Studies Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-6-2020 Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Meill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Meill, Kyung Peggy, "Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā" (2020). Mindfulness Studies Theses. 29. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mindfulness Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ i Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Kim Meill Lesley University May 2020 Dr. Melissa Jean and Dr. Andrew Olendzki DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ ii Abstract A literary work provides a window into the world of a writer, revealing her most intimate and forthright perspectives, beliefs, and emotions – this within a scope of a certain time and place that shapes the milieu of her life. The Therīgāthā, an anthology of 73 poems found in the Pali canon, is an example of such an asseveration, composed by theris (women elders of wisdom or senior disciples), some of the first Buddhist nuns who lived in the time of the Buddha 2500 years ago. The gathas (songs or poems) impart significant details concerning early Buddhism and some of its integral elements of mental and spiritual development. -

Soto Zen: an Introduction to Zazen

SOT¯ O¯ ZEN An Introduction to Zazen SOT¯ O¯ ZEN: An Introduction to Zazen Edited by: S¯ot¯o Zen Buddhism International Center Published by: SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO 2-5-2, Shiba, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-8544, Japan Tel: +81-3-3454-5411 Fax: +81-3-3454-5423 URL: http://global.sotozen-net.or.jp/ First printing: 2002 NinthFifteenth printing: printing: 20122017 © 2002 by SOTOSHU SHUMUCHO. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan Contents Part I. Practice of Zazen....................................................7 1. A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the Practice of the Bodhisattva Way 9 2. How to Do Zazen 25 3. Manners in the Zend¯o 36 Part II. An Introduction to S¯ot¯o Zen .............................47 1. History and Teachings of S¯ot¯o Zen 49 2. Texts on Zazen 69 Fukan Zazengi 69 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Bend¯owa 72 Sh¯ob¯ogenz¯o Zuimonki 81 Zazen Y¯ojinki 87 J¯uniji-h¯ogo 93 Appendixes.......................................................................99 Takkesa ge (Robe Verse) 101 Kaiky¯o ge (Sutra-Opening Verse) 101 Shigu seigan mon (Four Vows) 101 Hannya shingy¯o (Heart Sutra) 101 Fuek¯o (Universal Transference of Merit) 102 Part I Practice of Zazen A Path of Just Sitting: Zazen as the 1 Practice of the Bodhisattva Way Shohaku Okumura A Personal Reflection on Zazen Practice in Modern Times Problems we are facing The 20th century was scarred by two World Wars, a Cold War between powerful nations, and countless regional conflicts of great violence. Millions were killed, and millions more displaced from their homes. All the developed nations were involved in these wars and conflicts. -

Zen Masters at Play and on Play: a Take on Koans and Koan Practice

ZEN MASTERS AT PLAY AND ON PLAY: A TAKE ON KOANS AND KOAN PRACTICE A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Brian Peshek August, 2009 Thesis written by Brian Peshek B.Music, University of Cincinnati, 1994 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Jeffrey Wattles, Advisor David Odell-Scott, Chair, Department of Philosophy John R.D. Stalvey, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Chapter 1. Introduction and the Question “What is Play?” 1 Chapter 2. The Koan Tradition and Koan Training 14 Chapter 3. Zen Masters At Play in the Koan Tradition 21 Chapter 4. Zen Doctrine 36 Chapter 5. Zen Masters On Play 45 Note on the Layout of Appendixes 79 APPENDIX 1. Seventy-fourth Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 80 “Jinniu’s Rice Pail” APPENDIX 2. Ninty-third Koan of the Blue Cliff Record: 85 “Daguang Does a Dance” BIBLIOGRAPHY 89 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are times in one’s life when it is appropriate to make one’s gratitude explicit. Sometimes this task is made difficult not by lack of gratitude nor lack of reason for it. Rather, we are occasionally fortunate enough to have more gratitude than words can contain. Such is the case when I consider the contributions of my advisor, Jeffrey Wattles, who went far beyond his obligations in the preparation of this document. From the beginning, his nurturing presence has fueled the process of exploration, allowing me to follow my truth, rather than persuading me to support his. -

Spring 2018 Ango Training Commitment Training Retreats

Mountains and Rivers Order – Spring 2018 Ango Training Commitment Name: ______________________________________ Ango is a wonderful time to work toward making our lives more unified with practice. In addition to practicing moment-to-moment awareness in your daily activities, what other ways can you bring yourself into contact with the dharma during the day? Let this question guide you as you formulate your commitments for the ango. Ideally, your ango will include deliberate periods of practice in which you set aside time for one or two of the Eight Gates, as well as an ongoing effort to bring elements of the Eight Gates into the midst of your regular routines. Return this sheet to the Monastery Training Office by 2/27/18. Consider joining the sangha for the Ango Opening Ceremony on Sunday, March 4 at ZMM or Sunday, March 11th at the Temple. Please call the Training Office if you have questions. Training Retreats Training within the sangha is an essential aspect of Ango. Indicate the two retreats, at least one of them at the Monastery, that you commit to attending. 1. An Intensive Meditation Retreat at Zen Mountain Monastery: Note: The Peaceful Dwelling Intensive, Sesshin, and the Ango Intensive all fulfill this requirement. 2. A Second Retreat at ZMM, ZCNYC, or an MRO Affiliate*: Any retreat, zazenkai or a second sesshin fulfills this requirement; so does a short period of residency at the Monastery (we especially encourage this for MRO students). Please note that for the first time, we are offering a zazenkai at the Monastery this ango, in addition to those regularly offered at the Temple.