Grand Ducal Role and Identity As a Reflection on the Interaction of State and Dynasty in Imperial Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 By Thomas Lucius Lowish A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor Kinch Hoekstra Spring 2021 Abstract Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 by Thomas Lucius Lowish Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Historians of Russian monarchy have avoided the concept of sovereignty, choosing instead to describe how monarchs sought power, authority, or legitimacy. This dissertation, which centers on Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia between 1762 and 1796, takes on the concept of sovereignty as the exercise of supreme and untrammeled power, considered legitimate, and shows why sovereignty was itself the major desideratum. Sovereignty expressed parity with Western rulers, but it would allow Russian monarchs to bring order to their vast domain and to meaningfully govern the lives of their multitudinous subjects. This dissertation argues that Catherine the Great was a crucial figure in this process. Perceiving the confusion and disorder in how her predecessors exercised power, she recognized that sovereignty required both strong and consistent procedures as well as substantial collaboration with the broadest possible number of stakeholders. This was a modern conception of sovereignty, designed to regulate the swelling mechanisms of the Russian state. Catherine established her system through careful management of both her own activities and the institutions and servitors that she saw as integral to the system. -

History of Russia(1855-1953)

E-content for B.A Third Year (History Honours) Paper VIII (C) History of Russia(1855-1953) TOPIC NO. 2- CZAR ALEXANDER II: REFORMS By Dr. Divya Kumar Assistant Professor Department of History B.D College Patliputra University Patna [email protected] Dr Divya Kumar, B D College, Patliputra University, Patna. 1 Czar Alexander II : Reforms LESSON PLAN Introduction Alexander II- A Brief Profile Condition of Russia at the Time of His Accession His Reforms His Foreign Policy An Assessment of His Reforms INTRODUCTION Czar Alexander II of Russia, the successor of Czar Nicholas I is known in history for the numerous reforms he introduced in his country since the days of Peter the Great. Interestingly, his reign from 1855 and 1881, that is, till his death, can be divided into two phases. His progressive policies on the domestic front found expression only in the first decade of his reign, the reformist zeal unfortunately being cut short after an assassination bid on him in 1866. Thereafter, following his father’s footsteps, Alexander II reverted to suppression. Likewise, his foreign policy too showed a combination of liberalism and conservatism, depending on the countries and circumstances. ALEXANDER II- A BRIEF PROFILE Alexander II was born in Moscow on 29th of April, 1818. He was the eldest son of Czar Nicholas I and Charlotte, the daughter of Frederick William III of Prussia. His earlier name was Alexander Nikolaevich. Belonging to the Dr Divya Kumar, B D College, Patliputra University, Patna. 2 Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov House,he became the heir apparent from 1825 onwards. -

Fact Sheet Form the Worldwide Incidents Team

UNCLASSIFIED A Fact Sheet form the Worldwide Incidents Team National Counterterrorism Center 12 December 2007 Did you know the first suicide bombing may have occurred in 1881? On 13 March 1881 (NS)1, near the Winter Palace, St. Petersburg, Russia, an assailant threw an improvised explosive device (IED) under the armored carriage of the Tsar where it exploded, killing one bodyguard, injuring the driver, and several civilian bystanders, and damaging the carriage. The assailant was arrested immediately by other guards. While Tsar Alexander II inspected the site of the explosion, a suicide bomber approached and threw another IED at the Tsar’s feet where it exploded, fatally wounding the Tsar and critically injuring 20 others. On the same day at 3:30 PM, the Tsar died from his wounds. Members of the People’s Will, a Russian revolutionary organization, were arrested, tried and executed for the assassination. Tsar Alexander II of Russia and his assassin, Ignacy Hryniewiecki. The second bomb severed one of Alexander’s legs and shattered the other.2 He was taken to the nearby Winter Palace where he bled to death. He was alive long enough to receive communion, and for family to be with him in his last moments.3 At his side were Alexander III and Nicholas II who would become future Tsars. Scarred by what they had witnessed, it is believed they suppressed civil liberties to prevent befalling the same fate. It was later learned that a third assailant was waiting within the crowd and prepared to detonate a bomb had the first two bombings failed.4 Some credit this attack as the first recorded suicide bombing in history. -

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800S-1900S

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800s-1900s February 2003 Katrin Bozeva-Abazi Department of History McGill University, Montreal A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Contents 1. Abstract/Resume 3 2. Note on Transliteration and Spelling of Names 6 3. Acknowledgments 7 4. Introduction 8 How "popular" nationalism was created 5. Chapter One 33 Peasants and intellectuals, 1830-1914 6. Chapter Two 78 The invention of the modern Balkan state: Serbia and Bulgaria, 1830-1914 7. Chapter Three 126 The Church and national indoctrination 8. Chapter Four 171 The national army 8. Chapter Five 219 Education and national indoctrination 9. Conclusions 264 10. Bibliography 273 Abstract The nation-state is now the dominant form of sovereign statehood, however, a century and a half ago the political map of Europe comprised only a handful of sovereign states, very few of them nations in the modern sense. Balkan historiography often tends to minimize the complexity of nation-building, either by referring to the national community as to a monolithic and homogenous unit, or simply by neglecting different social groups whose consciousness varied depending on region, gender and generation. Further, Bulgarian and Serbian historiography pay far more attention to the problem of "how" and "why" certain events have happened than to the emergence of national consciousness of the Balkan peoples as a complex and durable process of mental evolution. This dissertation on the concept of nationality in which most Bulgarians and Serbs were educated and socialized examines how the modern idea of nationhood was disseminated among the ordinary people and it presents the complicated process of national indoctrination carried out by various state institutions. -

The Education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov The

Agata Strzelczyk DOI: 10.14746/bhw.2017.36.8 Department of History Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Abstract This article concerns two very different ways and methods of upbringing of two Russian tsars – Alexander the First and Nicholas the First. Although they were brothers, one was born nearly twen- ty years before the second and that influenced their future. Alexander, born in 1777 was the first son of the successor to the throne and was raised from the beginning as the future ruler. The person who shaped his education the most was his grandmother, empress Catherine the Second. She appoint- ed the Swiss philosopher La Harpe as his teacher and wanted Alexander to become the enlightened monarch. Nicholas, on the other hand, was never meant to rule and was never prepared for it. He was born is 1796 as the ninth child and third son and by the will of his parents, Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Fyodorovna he received education more suitable for a soldier than a tsar, but he eventually as- cended to the throne after Alexander died. One may ask how these differences influenced them and how they shaped their personalities as people and as rulers. Keywords: Romanov Children, Alexander I and Nicholas I, education, upbringing The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Among the ten children of Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, two sons – the oldest Alexander and Nicholas, the second youngest son – took the Russian throne. These two brothers and two rulers differed in many respects, from their characters, through poli- tics, views on Russia’s place in Europe, to circumstances surrounding their reign. -

Eugene Miakinkov

Russian Military Culture during the Reigns of Catherine II and Paul I, 1762-1801 by Eugene Miakinkov A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©Eugene Miakinkov, 2015 Abstract This study explores the shape and development of military culture during the reign of Catherine II. Next to the institutions of the autocracy and the Orthodox Church, the military occupied the most important position in imperial Russia, especially in the eighteenth century. Rather than analyzing the military as an institution or a fighting force, this dissertation uses the tools of cultural history to explore its attitudes, values, aspirations, tensions, and beliefs. Patronage and education served to introduce a generation of young nobles to the world of the military culture, and expose it to its values of respect, hierarchy, subordination, but also the importance of professional knowledge. Merit is a crucial component in any military, and Catherine’s military culture had to resolve the tensions between the idea of meritocracy and seniority. All of the above ideas and dilemmas were expressed in a number of military texts that began to appear during Catherine’s reign. It was during that time that the military culture acquired the cultural, political, and intellectual space to develop – a space I label the “military public sphere”. This development was most clearly evident in the publication, by Russian authors, of a range of military literature for the first time in this era. The military culture was also reflected in the symbolic means used by the senior commanders to convey and reinforce its values in the army. -

Jan Sobczak Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia

Jan Sobczak Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia Echa Przeszłości 12, 143-156 2011 ECHA PRZESZŁOŚCI XII, 2011 ISSN 1509-9873 Jan Sobczak ALEXEI NIKOLAEVICH, TSAREVICH OF RUSSIA This article does not aspire to give an exhaustive account of the life of Alexei Nikolaevich, not only for reasons of limited space. The role played by the young lad who was much loved by the nation, became the Russian tsesarevich and was murdered at the tender age of 14, would not justify such an effort. In addition to delivering general biographical information about Alexei that can be found in a variety of sources, I will attempt to throw some light on the less known aspects of his life that profoundly affected the fate of the Russian Empire and brought tragic consequences for the young imperial heir1. Alexei Nikolaevich was born in Peterhof on 12 August (30 July) 1904 on Friday at noon, during an unusually hot summer that had started already in February, at the beginning of Russia’s much unfortunate war against Japan. Alexei was the fifth child and the only son of Nicholas II and Alexandra Feodorovna. He had four older sisters who were the Grand Duchesses: Olga (8.5 years older than Alexei), Tatiana (7 years older), Maria (5 years older) and Anastasia (3 years older). In line with the law of succession, Alexei automatically became heir to the throne, and his birth was heralded to the public by a 300-gun salute from the Peter and Paul Fortress. According to Nicholas II, the imperial heir was named Alexei to break away from a nearly century-old tradition of naming the oldest sons Alexander and Nicholas and to commemorate Peter the Great’s father, Alexei Mikhailovich, the second tsar of the Romanov dynasty that had ruled over Russia for nearly 300 years from the 17th century. -

„Golden Age”: Introduction Into the 1803–1832 Epochs

ARCHIWUM EMIGRACJI Studia – Szkice – Dokumenty http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/AE.2018-2019.008 Toruń, Rok 2018/2019, Zeszyt 1–2 (26–27) ___________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ UNIWERSYTET W WILNIE THE UNIVERSITY OF VILNIUS AND ITS „GOLDEN AGE”: INTRODUCTION INTO THE 1803–1832 EPOCHS Alfredas BUMBLAUSKAS (Vilnius University) ORCID: 0000-0002-3067-786X Loreta SKURVYDAITĖ (Vilnius University) ORCID: 0000-0002-4350-4482 1. WHAT IS THE UNIVERSITY OF VILNIUS? It is a paradoxically simple question. Though it will not seem so simple if we ask another question — what is Vilnius? Today it is the capital of the Republic of Lithuania, a member state of the European Union. However, at the beginning of the 19th century, the epoch of great importance to us, it was turned into a provincial town of the Russian Empire. Prior to that, for a long time, it was the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which existed in the 13th–18th century. In the 20th century, after the reestablishment of the Polish and Lithuanian states, it did not become the capital of Lithuania (the city of Kaunas became its provisional capital); Vilnius was incorporated into Poland and became a city of the Polish province. In 1939, on Stalin’s initiative, it was taken away from Poland and returned to Lithuania, at the same time annexing Lithuania to the Soviet Empire. All this has to be kept in mind if we want to understand the question what the University of Vilnius is. And what was it during the period between 1803 and 1832? 79 At first glance the answer seems simple — this is an institution founded by the Jesuits and Stephen Bathory in 1579. -

|FREE| Alexander II: the Last Great Tsar

ALEXANDER II: THE LAST GREAT TSAR EBOOK Author: Edvard Radzinsky, Vice President Antonina W Bouis Number of Pages: 462 pages Published Date: 14 Nov 2006 Publisher: SIMON & SCHUSTER Publication Country: New York, NY, United States Language: English ISBN: 9780743284264 Download Link: CLICK HERE Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar Online Read London: Longman, Radzinsky also supported the hypotesis by Viktor Suvorov that Stalin had prepared a preemptive strike against Nazi Germany Retrieved 19 March This combination led to Alexander being well-prepared and more liberal than his father. Felt like it wandered. My first baptism into Russian history of this time period, and Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar may never recover. When they abducted The dying emperor was given Communion and Last Rites. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. What if they had just once followed the parable of the prodigal Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar, which Dostoevsky had entreated his children to remember. The assassination triggered major suppression of civil liberties in Russia, and police brutality burst back in full force after experiencing some restraint under the reign of Alexander II, whose death was witnessed first-hand by his son, Alexander IIIand his grandson, Nicholas IIboth future emperors who vowed not to have the same fate befall them. Peter III of Russia 4. Reviews Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar Wikisource has original works written by or about: Alexander II of Russia. A Hollywood Story. Alexander Nevsky Recipients of the Order of St. A host of new reforms followed in diverse areas. Wikisource has original text related to this article: An intimate glimpse into the family life of Alexander II Jan 31, Rithun Regi rated it really liked it. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-63941-6 - The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume II: Imperial Russia, 1689–1917 Edited by Dominic Lieven Index More information Index Abaza, A. A., member of State Council 471 Aksakov, Konstantin Sergeevich, Slavophile Abdul Hamid II, Ottoman ruler 20 writer 127 Ablesimov, Aleksandr, playwright 86 Fundamental Principles of Russian abortion 324 History 127 About This and That (journal) 86 Aksel’rod, Pavel, Menshevik 627 Abramtsevo estate, artists’ colony 105 Alash Orda (Loyalty) party, Kazakh 221 Adams, John Quincy 519 Alaska Adrianople, Treaty of (1829) 559 Russian settlements in 36 adultery 309, 336, 339 sold to USA (1867) 564 advertising 320, 324 alcoholism 185, 422, 422n.77 Aerenthal, Count Alois von, Austrian foreign Alekseev, Admiral E. I., Viceroy 586 minister 570 Alekseev, A. V.,army commander-in-chief Afanasev, Aleksandr, anthology of (1917) 664 folk-tales 98 Aleksei see Alexis al-Afgani, Jamal al-Din, Muslim reformer Alexander I, Tsar (1801–25) 219 conception of Russian destiny 149 Afghanistan 563, 566, 569 and conspiracy theories 153 Africa, ‘Scramble’ for 576 court agricultural reforms favourites 152, 438 Stolypin’s 181, 389, 417, 464, 613 liberal advisers 149, 526 and vision of social justice 24 and economy 399–400 agriculture 232, 379, 410 and Europe 149, 520 1870s depression 241 ‘Holy Alliance’ 556 arable 375 foreign policy 519–28, 554, 556–8 and environment 373, 390 and Britain 523, 524, 525 expansion southwards 493 and France 520, 523 extensive cultivation 374, 375, 387 and Jews 190 -

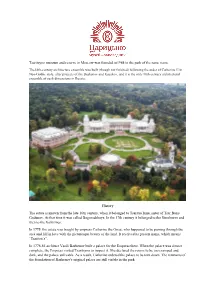

Tsaritsyno Museum and Reserve in Moscow Was Founded In1984 in the Park of the Same Name

Tsaritsyno museum and reserve in Moscow was founded in1984 in the park of the same name. The18th-century architecture ensemble was built (though not finished) following the order of Catherine II in Neo-Gothic style, after projects of the Bazhenov and Kazakov, and it is the only 18th-century architectural ensemble of such dimensions in Russia. History The estate is known from the late 16th century, when it belonged to Tsaritsa Irina, sister of Tsar Boris Godunov. At that time it was called Bogorodskoye. In the 17th century it belonged to the Streshnevs and then to the Galitzines. In 1775, the estate was bought by empress Catherine the Great, who happened to be passing through the area and fell in love with the picturesque beauty of the land. It received its present name, which means “Tsaritsa’s”. In 1776-85 architect Vasili Bazhenov built a palace for the Empress there. When the palace was almost complete, the Empress visited Tsaritsyno to inspect it. She declared the rooms to be too cramped and dark, and the palace unlivable. As a result, Catherine ordered the palace to be torn down. The remnants of the foundation of Bazhenov's original palace are still visible in the park. In 1786, Matvey Kazakov presented new architectural plans, which were approved by Catherine. Kazakov supervised the construction project until 1796 when the construction was interrupted by Catherine's death. Her successor, Emperor Paul I of Russia showed no interest in the palace and the massive structure remained unfinished and abandoned for more than 200 years, until it was completed and extensively reworked in 2005-07. -

December 2012

PRESS RELEASE 4 April 2019 Russia, Royalty & the Romanovs The Queen's Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse 21 June – 3 November 2019 For more than 300 years Britain has been linked to Russia through exploration and discovery, diplomatic alliances and, latterly, by familial and dynastic ties. Russia, Royalty & the Romanovs, opening on 21 June 2019, explores the relationship between the two countries and their royal families through more than 170 works of art in the Royal Collection, many of which were exchanged as diplomatic gifts or intimate personal mementos. The first Russian ruler to set foot on English soil was Tsar Peter I, known as Peter the Great. In 1698 he visited London for three months and met with the British King, William III, as part of a diplomatic and fact-finding tour of Western Europe. On his departure Peter presented the King with his portrait, painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller. The young Tsar is depicted wearing Laurits Regner Tuxen, the mantle of a ruler and the armour of a warrior, The Marriage of Nicholas II, Tsar of looking to the West and hoping to establish a new, Russia, 26th November 1894, 1896 ‘open’ Russia. During the reign of the Empress Catherine II (Catherine the Great), Russia’s borders expanded to the south and west, and the country was established as one of the great powers in Europe. The Empress’s coronation portrait by Vigilius Eriksen, c.1765–9, is a clear statement of magnificence and power. It was recorded as hanging in the Privy Chamber at Kensington Palace in 1813, and may have been a diplomatic gift to George III.