The Russian Empire As a "Civilized State": International Law As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andtheirassistancetorussiainthe

Panslawizm – wczoraj, dziś, jutro Borche Nikolow Uniwersytet Świętych Cyryla i Metodego w Skopje, Instytut Historii, Republika Macedonii The Balkan Slavs solidarity during the Great Eastern Crisis (1875–1878) and their assistance to Russia in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) Solidarność Słowian bałkańskich w czasie Wielkiego Kryzysu Wschodniego (1875-1878), a ich pomoc Rosji w wojnie rosyjsko-tureckiej (1877–1878) Abstrakt: Niezdolność armii Imperium Osmańskiego do stłumienia buntu w Bośni i Hercegowinie w 1875 wywołała podniecenie wśród narodów słowiańskich na calych Bałkanach. Słowiańskie narody Bałkanów dołączyły do swoich braci z Bośni i Hercegowiny w walce przeciwko Turkom. W latach Wielkiego Kryzysu Wschodniego (1875-1878) Serbia i Czarnogóra wypowiedziała wojnę Imprerium Osmańskiemu, a w Bułgarii i w Tureckiej Macedonii wybuchły liczne powstania. Narody bałkańskie wspierały się wzajemnie w walce przeciwko Imprerium, pomogły także armii rosyjskiej w czasie woj- ny rosyjsko-tureckiej (1877–1878) wysyłając wolontariuszy, jak również ubrania, żywność, leki, itp, mając nadzieję, że wielki słowiański brat z północy pomoże im wypędzić Turków z Bałkan i przynie- sie im wyzwolenie i wolność. Słowa kluczowe: Wielki Kryzys Wschodni, Imperium Osmańskie Keywords: Big Crisis East, the Ottoman Empire 91 Plight of the Christian Slav population in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the second half of the 19th century, culminated in 1975 with the uprising, which started the Great Eastern Crisis. The Inability of the Ottoman army to quickly put down the rebellion and the local population resistance, caused excite- ment amongst the Slavic people throughout the Balkans. They hoped that the time for their liberation from the Ottoman rule had come. As a result of that sit- uation, the Slavic peoples of the Balkans joined their brothers from Bosnia and Herzegovina with the fight against the Ottomans. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800S-1900S

The Shaping of Bulgarian and Serbian National Identities, 1800s-1900s February 2003 Katrin Bozeva-Abazi Department of History McGill University, Montreal A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Contents 1. Abstract/Resume 3 2. Note on Transliteration and Spelling of Names 6 3. Acknowledgments 7 4. Introduction 8 How "popular" nationalism was created 5. Chapter One 33 Peasants and intellectuals, 1830-1914 6. Chapter Two 78 The invention of the modern Balkan state: Serbia and Bulgaria, 1830-1914 7. Chapter Three 126 The Church and national indoctrination 8. Chapter Four 171 The national army 8. Chapter Five 219 Education and national indoctrination 9. Conclusions 264 10. Bibliography 273 Abstract The nation-state is now the dominant form of sovereign statehood, however, a century and a half ago the political map of Europe comprised only a handful of sovereign states, very few of them nations in the modern sense. Balkan historiography often tends to minimize the complexity of nation-building, either by referring to the national community as to a monolithic and homogenous unit, or simply by neglecting different social groups whose consciousness varied depending on region, gender and generation. Further, Bulgarian and Serbian historiography pay far more attention to the problem of "how" and "why" certain events have happened than to the emergence of national consciousness of the Balkan peoples as a complex and durable process of mental evolution. This dissertation on the concept of nationality in which most Bulgarians and Serbs were educated and socialized examines how the modern idea of nationhood was disseminated among the ordinary people and it presents the complicated process of national indoctrination carried out by various state institutions. -

By Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy Aleksey Tolstoy

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Упырь by Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy Aleksey Tolstoy. Russian poet and playwright (b. 24 August/5 September 1817 in Saint Petersburg; d. 28 September/10 October 1875 at Krasny Rog, in Chernigov province), born Count Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy (Алексей Константинович Толстой). Contents. Biography. Descended from illustrious aristocratic families on both sides, Aleksey was a distant cousin of the novelist Lev Tolstoy. Shortly after his birth, however, his parents separated and he was taken by his mother to Chernigov province in the Ukraine where he grew up under the wing of his uncle, Aleksey Perovsky (1787–1836), who wrote novels and stories under the pseudonym "Anton Pogorelsky". With his mother and uncle Aleksey travelled to Europe in 1827, touring Italy and visiting Goethe in Weimar. Goethe would always remain one of Tolstoy's favourite poets, and in 1867 he made notable translations of Der Gott und die Bajadere and Die Braut von Korinth . In 1834, Aleksey was enrolled at the Moscow Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where his tasks included the cataloguing of historical documents. Three years later he was posted to the Russian Embassy at the Diet of the German Confederation in Frankfurt am Main. In 1840, he returned to Russia and worked for some years at the Imperial Chancery in Saint Petersburg. During the 1840s Tolstoy wrote several lyric poems, but they were not published until many years later, and he contented himself with reading them to his friends and acquaintances from the world of Saint Petersburg high society. At a masked ball in the winter season of 1850/51 he saw for the first time Sofya Andreyevna Miller (1825–1895), with whom he fell in love, dedicating to her the fine poem Amid the Din of the Ball (Средь шумного бала), which Tchaikovsky would later immortalize in one of his most moving songs (No. -

Gladstone's Role During the Great Eastern Crisis

Gladstone’s Role during the Great Eastern Crisis Jelena Milojković -Djurić Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts In early July of 1975 the uprising in Herzegovina spread quickly throughout the neighboring region of Bosnia. The difficult fate of the South Slavs under Ottoman occupation became known to the whole of Europe. Gradually a wide spread revolt engulfed also Bulgaria and Romania. In order to help the suffering population, an International Relief Committee was formed in Paris. The Relief Committee was headed by the Serbian Metropolitan Mihail Jovanović and aided by the Croatian Bishop Josip Strossmayer. The Committee was ably supported by the Slavic Benevolent Society in Russia, with its outstanding members, including the writer Ivan Aksakov and countess Antonina Bliudova. During the height of the Eastern Crisis, Lord William Evart Gladstone, the distinguished English statesman, stood out as the most influential spokesmen on behalf of the South Slavs. His famous speeches in Parliament, and notably his book, Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East, instigated a sincere concern and willingness to help among the public at large. Gladstone’s support was very significant in view of the official English position under the aegis of the Premier Benjamin Disraeli. Disraeli aspired to preserve the precarious European equilibrium inclusive of the Turkish presence in the Balkans. He believed that the disappearance of Turkey from the Balkans would produce difficulties for England as well as for worldwide political relations. In reality, Disraeli and the English government acted against the concerns of eminent personalities and of English society at large. As may be expected, Disraeli’s position drew criticism not only from his English peers but from a number of 1 Serbian and Russian personalities. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-63941-6 - The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume II: Imperial Russia, 1689–1917 Edited by Dominic Lieven Index More information Index Abaza, A. A., member of State Council 471 Aksakov, Konstantin Sergeevich, Slavophile Abdul Hamid II, Ottoman ruler 20 writer 127 Ablesimov, Aleksandr, playwright 86 Fundamental Principles of Russian abortion 324 History 127 About This and That (journal) 86 Aksel’rod, Pavel, Menshevik 627 Abramtsevo estate, artists’ colony 105 Alash Orda (Loyalty) party, Kazakh 221 Adams, John Quincy 519 Alaska Adrianople, Treaty of (1829) 559 Russian settlements in 36 adultery 309, 336, 339 sold to USA (1867) 564 advertising 320, 324 alcoholism 185, 422, 422n.77 Aerenthal, Count Alois von, Austrian foreign Alekseev, Admiral E. I., Viceroy 586 minister 570 Alekseev, A. V.,army commander-in-chief Afanasev, Aleksandr, anthology of (1917) 664 folk-tales 98 Aleksei see Alexis al-Afgani, Jamal al-Din, Muslim reformer Alexander I, Tsar (1801–25) 219 conception of Russian destiny 149 Afghanistan 563, 566, 569 and conspiracy theories 153 Africa, ‘Scramble’ for 576 court agricultural reforms favourites 152, 438 Stolypin’s 181, 389, 417, 464, 613 liberal advisers 149, 526 and vision of social justice 24 and economy 399–400 agriculture 232, 379, 410 and Europe 149, 520 1870s depression 241 ‘Holy Alliance’ 556 arable 375 foreign policy 519–28, 554, 556–8 and environment 373, 390 and Britain 523, 524, 525 expansion southwards 493 and France 520, 523 extensive cultivation 374, 375, 387 and Jews 190 -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

2. Historical Overview: Social Order in Mā Warāʾ Al-Nahr

2. Historical Overview: Social Order in Mā Warāʾ al-Nahr With the beginning of Uzbek dominance in southern Central Asia around the year 1500, a fresh wave of Turkic nomads was brought in and added a new element to the populace of the region.1 Initially the establishment of Uzbek rule took the form of a nomadic conquest aiming to gain access to the irrigated and urban areas of Transoxania. The following sedentarization of the Uzbek newcomers was a long-term process that took three and perhaps even more centuries. In the course of time, the conquerors mixed with those Turkic groups that had already been settled in the Oxus region for hundreds of years, and, of course, with parts of the sedentary Persian-speaking population.2 Based on the secondary literature, this chapter is devoted to the most important historical developments in Mā Warāʾ al-Nahr since the beginning of the sixteenth century. By recapitulating the milestones of Uzbek rule, I want to give a brief overview of the historical background for those who are not familiar with Central Asian history. I will explore the most significant elements of the local social order at the highest level of social integration: the rulers and ruling clans. In doing so, I will spotlight the political dynamics resulting from the dialectics of cognitive patterns and institutions that make up local worldviews and their impact on the process of institutionalizing Abū’l-Khairid authority. The major focus will be on patronage. As the current state of knowledge shows, this institution was one of the cornerstones of the social order in the wider region until the Mongol invasion. -

Mpub10110094.Pdf

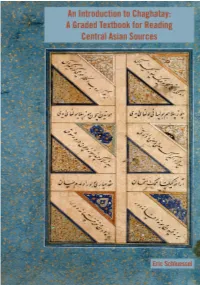

An Introduction to Chaghatay: A Graded Textbook for Reading Central Asian Sources Eric Schluessel Copyright © 2018 by Eric Schluessel Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: 10.3998/mpub.10110094 ISBN 978-1-60785-495-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60785-496-8 (e-book) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high-quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, offering streamlined selection, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a complement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www.maizebooks.org Cover Illustration: "Islamic Calligraphy in the Nasta`liq style." (Credit: Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/chengwfg/, licensed under CC BY 4.0) Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction vi How to Read the Alphabet xi 1 Basic Word Order and Copular Sentences 1 2 Existence 6 3 Plural, Palatal Harmony, and Case Endings 12 4 People and Questions 20 5 The Present-Future Tense 27 6 Possessive -

Alexandr Mikhailovich Dondukov-Korsakov

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by GAMS - Asset Management System for the Humanities VASE Visual Archive Southeastern Europe Permalink: http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.383 Prince (knyaz) Alexandr Mikhailovich Dondukov-Korsakov Object: Prince (knyaz) Alexandr Mikhailovich Dondukov-Korsakov Description: Half length portrait in an oval frame, depicting a man in military uniform with insignias of honour. Comment: Prince Alexandr Mikhailovich Dondukov- Korsakov (1820 - 1893) was a Russian officer, General of the Cavalry, and politician. He took part in the Caucasian War, the Crimean War and the Russo- Ottoman War of 1877–1878. As of 1878–1879 he was Russia's Supreme Commissar in Bulgaria and helped draft the organizational statutes on which the first Bulgarian constitution was based. He acted also as Governor of Kharkov, Prince (knyaz) Alexandr Mikhailovich Odessa, and Caucasus. According to a Dondukov-Korsakov © Scientific Archive of the Bulgarian hand-written inscription on the back of Academy of Sciences a identical photograph, kept in Anastas Jovanović's album, the photo was taken by Iv. A. Karastoyanov. Relations: http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1032 Date: Not before 1878, Not after 1879 Location: Sofia Country: Bulgaria Type: Photograph Creator: Karastoyanov, Ivan Anastasov, (Photographer) Dimensions: Artefact: 103mm x 65mm Image: 77mm x 53mm Format: Carte de visite Technique: Not specified Keywords: 150 Behavior Processes and Personality > 156 Social Personality Prince (knyaz) Alexandr Mikhailovich 550 Individuation and Mobility > 551 Personal Dondukov-Korsakov © Scientific Archive of the Bulgarian Names Academy of Sciences 710 Military Technology 700 Armed Forces 720 War 640 State http://gams.uni-graz.at/vase 1 VASE Visual Archive Southeastern Europe Permalink: http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.383 Copyright: Научен архив на Българската академия на науките Archive: Scientific Archive of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Inv. -

Letters from Vidin: a Study of Ottoman Governmentality and Politics of Local Administration, 1864-1877

LETTERS FROM VIDIN: A STUDY OF OTTOMAN GOVERNMENTALITY AND POLITICS OF LOCAL ADMINISTRATION, 1864-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Mehmet Safa Saracoglu ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Carter Vaughn Findley, Adviser Professor Jane Hathaway ______________________ Professor Kenneth Andrien Adviser History Graduate Program Copyright by Mehmet Safa Saracoglu 2007 ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the local administrative practices in Vidin County during 1860s and 1870s. Vidin County, as defined by the Ottoman Provincial Regulation of 1864, is the area that includes the districts of Vidin (the administrative center), ‛Adliye (modern-day Kula), Belgradcık (Belogradchik), Berkofça (Bergovitsa), İvraca (Vratsa), Rahova (Rahovo), and Lom (Lom), all of which are located in modern-day Bulgaria. My focus is mostly on the post-1864 period primarily due to the document utilized for this dissertation: the copy registers of the county administrative council in Vidin. Doing a close reading of these copy registers together with other primary and secondary sources this dissertation analyzes the politics of local administration in Vidin as a case study to understand the Ottoman governmentality in the second half of the nineteenth century. The main thesis of this study contends that the local inhabitants of Vidin effectively used the institutional framework of local administration ii in this period of transformation in order to devise strategies that served their interests. This work distances itself from an understanding of the nineteenth-century local politics as polarized between a dominating local government trying to impose unprecedented reforms designed at the imperial center on the one hand, and an oppressed but nevertheless resistant people, rebelling against the insensitive policies of the state on the other. -

Russia's Imperial Encounter with Armenians, 1801-1894

CLAIMING THE CAUCASUS: RUSSIA’S IMPERIAL ENCOUNTER WITH ARMENIANS, 1801-1894 Stephen B. Riegg A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Louise McReynolds Donald J. Raleigh Chad Bryant Cemil Aydin Eren Tasar © 2016 Stephen B. Riegg ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Stephen B. Riegg: Claiming the Caucasus: Russia’s Imperial Encounter with Armenians, 1801-1894 (Under the direction of Louise McReynolds) My dissertation questions the relationship between the Russian empire and the Armenian diaspora that populated Russia’s territorial fringes and navigated the tsarist state’s metropolitan centers. I argue that Russia harnessed the stateless and dispersed Armenian diaspora to build its empire in the Caucasus and beyond. Russia relied on the stature of the two most influential institutions of that diaspora, the merchantry and the clergy, to project diplomatic power from Constantinople to Copenhagen; to benefit economically from the transimperial trade networks of Armenian merchants in Russia, Persia, and Turkey; and to draw political advantage from the Armenian Church’s extensive authority within that nation. Moving away from traditional dichotomies of power and resistance, this dissertation examines how Russia relied on foreign-subject Armenian peasants and elites to colonize the South Caucasus, thereby rendering Armenians both agents and recipients of European imperialism. Religion represented a defining link in the Russo-Armenian encounter and therefore shapes the narrative of my project. Driven by a shared ecumenical identity as adherents of Orthodox Christianity, Armenians embraced Russian patronage in the early nineteenth century to escape social and political marginalization in the Persian and Ottoman empires.