D0bc5-A-Woman-Of-Firsts-By-Edna-Adan-Ismail.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Genital Mutilation: Current Practices and Perceptions in Somaliland

Global Journal of Health Education and Promotion Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 42–57 http://dx.doi.org/10.18666/GJHEP-2016-V17-I2-7101 Female Genital Mutilation: Current Practices and Perceptions in Somaliland Trista Dawn Smith, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine Cristina Redko, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine Nikki Rogers, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine Edna Adan Ismail, Edna Adan University Hospital Abstract Background: Somaliland, Africa, has the highest prevalence of female genital mutilation (FGM) in the world despite its recognition as a human rights viola- tion and decades of campaigns to eliminate it. This study establishes baseline data for FGM prevalence in Somaliland and explores changing perceptions of FGM among Somalis. Method: A descriptive study was conducted among 6,108 women at the Edna Adan University Hospital (EAUH) from 2006–2013. Data were obtained regarding FGM status and knowledge and perception to- ward the practice. Chi-square analysis was conducted to compare current and previous studies conducted at EAUH. Results: The prevalence rate of FGM among respondents was 98.4% and procedures occurred at an average age of 8.47 years. Most participants (82.20%) underwent the most severe Type III or Pharaonic FGM. The most commonly cited reason for practicing FGM was to maintain cultural and traditional values (82.9%). Continuation of the practice was supported among 83.17% of respondents, the majority of whom reported a preference for the milder Type I or II Sunna FGM (95.15%). Women who at- tended university were subjected to FGM less than were their uneducated coun- terparts. -

Downloads/Ctrylst.Txt

[Type the company name] 1 [Type the document title] T HE S O M A L I I NSURGENCY THE GROWING THREAT O F TERROR’S RESURGENC E Master of Arts in Law and Diplomacy Capstone Project Submitted by Joshua Meservey May 2013 © 2013 Joshua Meservey http://fletcher.tufts.edu Josh Meservey 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 A BRIEF HISTORY 6 COLONIZATION 7 DEMOCRACY, DICTATORSHIP, DISINTEGRATION 10 THE ROOTS OF AL-SHABAAB 13 TERRORISM TRIUMPHANT 15 STIRRINGS OF HOPE 16 THE KIDS AREN’T ALRIGHT: AN ANALYSIS OF HARAKAT AL-SHABAAB AL- MUJAHIDEEN 18 IDEOLOGY AND STRUCTURE 18 TRANSNATIONAL TERRORIST LINKS 19 FUNDING 20 RECRUITMENT 27 REASONS FOR AL-SHABAAB’S LOSSES 42 SELF-INFLICTED WOUNDS 42 INTERNATIONAL EFFORTS 54 AL-SHABAAB’S RETURN TO INSURGENCY: HOP LIKE A FLEA 61 “DO YOU REALLY THINK THEY CAN CONTINUE LIKE THAT FOREVER?” 62 SOLUTION: COUNTERINSURGENCY 67 WIN THE PEOPLE 67 GEOGRAPHY, CULTURE, AND HISTORY 71 A COUNTERINSURGENCY REPORT CARD 89 TOO MANY MISTAKES 89 PLANNING: TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE 89 TRAINING: “SHOOT AND DUCK” 92 GOVERNMENT LEGITIMACY: “LEGITIMACY-DEFICIT”? 94 SECURITY: “IT IS HARD NOT TO WORRY” 97 COALITION POLITICS: WITH FRIENDS LIKE THESE 100 TREATMENT OF CIVILIANS: DO NO HARM 104 WHO IS WINNING? 108 THE WAY FORWARD 111 FOR THE SOMALI FEDERAL GOVERNMENT 111 FOR AMISOM AND ETHIOPIA 124 FOR THE UNITED STATES 130 CONCLUSION: DANGEROUS TIMES 139 ADDENDUM: THE WESTGATE MALL ATTACK 141 WORKS CITED 145 Josh Meservey 3 Executive Summary Al-Shabaab’s current fortunes appear bleak. It has been pushed from all of its major strongholds by a robust international effort, and its violent Salafism has alienated many Somalis. -

Edna Adan Ismail Address: Hargeisa City, Hargeisa Email: [email protected] Website: Mobile: 0025 22 44 26 922

Edna Adan Ismail Address: Hargeisa city, Hargeisa Email: [email protected] Website: www.ednahospital.org Mobile: 0025 22 44 26 922 Education and Awards 1954-1961: Scholarship from Britain and studied Nursing and Midwifery in the UK. 1983: USAID Scholarship and studied Family Planning in New York. 1987-1988: Bachelor of Science Degree in Hospital Management through distance learning from Clayton University, USA. 1997: Decorated by the Government of Djibouti, Commandeur De L'Ordre National Du 27 Juin and the UNDP Manager of the Year Award. 1998: Health Care in Developing Countries at Boston University, USA. 2002: Honorary Doctoral Degree for her Humanitarian Work from Clark University in the USA. 2007: Honorary Fellow of Cardiff University. School of Nursing 2008: The Medical Mission Hall of Fame of Ohio University, USA. 2009: The Chancellor's Gold Medal from the University of Pretoria, South Africa. 2010: The Legion d'Honneur from President Sarkozy of France. Career and International Responsibilities 1961-1963: After returning from studies in the UK, was in charge of Hargeisa Group Hospital Female Sections and Maternity 1963-1965: Founding Member and Secretary General of the Somali Red Crescent Society. During that time was also Training Midwives at the Health Personnel Training School. 1965 to end 1967: WHO Nurse Midwife Education in Libya January 1968: Returned to Somalia at end of 1967 when husband became Prime Minister of Somalia and continued with Diplomatic responsibilities and Charity work - After Somalia's Marxist Coup d'Etat when husband's Civilian Government was toppled by Siyad Barre, became a Political Prisoner under house arrest for six months. -

OUTCOME REPORT This Outcome Report Is the Result of the Somaliland Investment Forum Hargeisa Held on September 19-21, 2016

OUTCOME REPORT This outcome report is the result of the Somaliland Investment Forum Hargeisa held on September 19-21, 2016. Presented By Cover photos: Participants network at the SIF Hargeisa 2016. All photos in this report are by Jean-Pierre Larroque of One Earth Future unless otherwise noted. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................1 STATISTICS AND FIGURES ..............................................................................................................3 MEDIA COVERAGE ...........................................................................................................................4 AGENDA-AT-A-GLANCE ...................................................................................................................5 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS .......................................................................................................................6 KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................9 EVENT PHOTOS ..............................................................................................................................10 SPEAKER LIST .................................................................................................................................11 SPONSORS & PARTNERS -

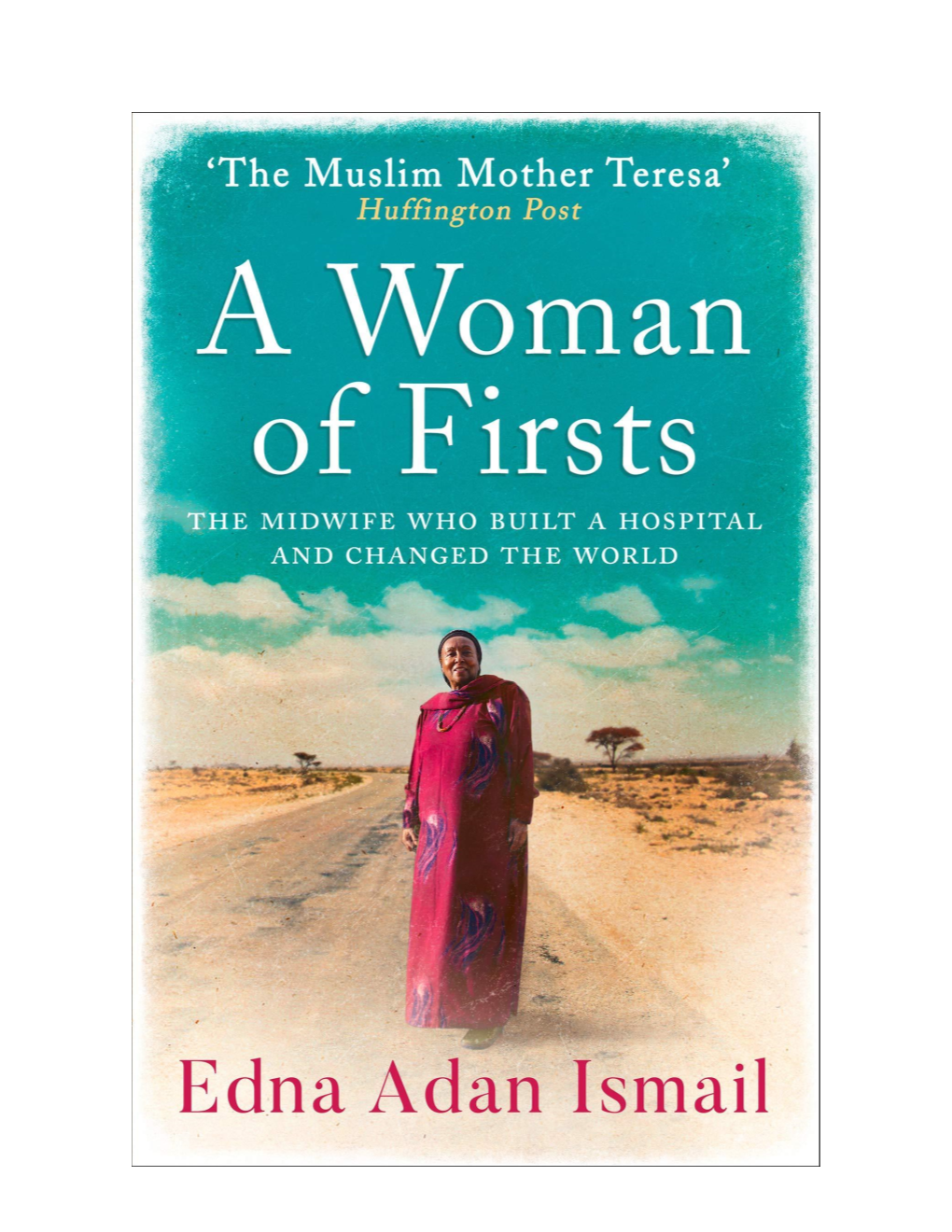

Books: a Woman of Firsts. the Midwife Who Built a Hospital And

Life & Times Books 3. Pereira Gray D, Sidaway-Lee K, White E,et al. A Woman of Firsts. The Midwife Who woman working was highly frowned upon. Continuity of care with doctors: a systematic Built A Hospital And Changed The World Her journey runs parallel to that review of continuity of care and mortality.BMJ Edna Adan Ismail of her homeland, which after gaining 8: Open 2018; e021161. Harper Collins, 2020, PB, 336pp, £9.99, independence from Britain in 1960, 4. Baker R, Freeman G, Haggerty JL,et al. 978-0008305383 quickly joins with Italian Somalia. Edna Primary medical care continuity and patient mortality a systematic review. Br J Gen marries Mohamed Egal who becomes Pract 2020; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/ prime minister of Somalia, and soon she bjgp20X712289 is attending state visits as the First Lady. 5. Barker I, Steventon A, Deeny SR. Association A coup ensues, and life in Somaliland between continuity of care in general practice becomes very difficult as civil war takes and hospital admissions for ambulatory care hold. sensitive conditions: cross sectional study of routinely collected, person level data. BMJ Edna begins working for the World 2017; 356: j84 Health Organization, and spends decades 6. De Maeseneer JM, De Prins L, Gosset C, helping to raise awareness of FGM (she Heyerick J. Provider continuity in family even helped coin the term). Her dream medicine: does it make a difference for total to build a hospital in her country remains health care costs? Ann Fam Med 2003; 1(3): forever present, despite several setbacks 144–148. -

PATIENCE and CARE Rebuilding Nursing and Midwifery, in Somaliland by Fouzia Mohamed Ismail Printed by 4 Print Ltd

POLICY VOICES SERIES POLICY PATIENCE AND CARE Rebuilding nursing and midwifery, in Somaliland By Fouzia Mohamed Ismail Printed by 4 Print Ltd. KT8 2RY 020 8941 0144 The Author The Policy Voices Series Fouzia Mohamed Ismail was educated in Burao and The Policy Voices Series highlights instances of personal Hargeisa, in Somaliland. In 1974, Fouzia graduated as a achievement with wider implications for policymakers in midwife and public health nurse in Mogadishu, capital of Africa. Somalia. For the next 15 years, midwifery and public In publishing these case stories, Africa Research Institute health nursing were the focus of her work. seeks to identify the factors which lie behind successful In 1989, during the civil war in Somalia, Fouzia moved to interventions, and to draw policy lessons from individual Canada, where she graduated with a BSc in nursing from experience. the University of Ottawa. Between 1990 and 2004 Fouzia The series also seeks to encourage competing ideas, worked at the South-East Ottawa Centre for a Healthy discussion and debate. The views expressed in the Policy Community, co-ordinating the promotion of adult health Voices Series are those of the author. and community health nursing. During her career in Canada, Fouzia received an award from the Lilly Foundation and the Canadian Diabetes Association for Acknowledgements primary and secondary care professionals working in diabetic care. She also received an award for leadership This manuscript was researched and edited by Edward in health promotion from the Somali Centre for Family Paice, based on transcripts of interviews with Fouzia Services, and the Canadian federal certificate of merit for Mohamed Ismail and others. -

Press Release SOPRI0829

PRESS RELEASE: August 20, 2006 SOPRI PROMTES INTERNATIONAL UNDERSTANDING OF SOMALILAND Somaliland Policy & Reconstruction Institute (SOPRI) promotes Somaliland to increase the awareness of the international community about Somaliland’s indisputable right for statehood. The more the Somaliland case is strongly pushed in Africa, Europe, North America and Asia by the the efforts of the government and the Diaspora communities acting in concert; the earlier the quest for recognition will be realized. SOPRI’s has so far focused its work in the United States. We hope to inspire other communities to engage in similar activities in the key countries where Somaliland interest must be promoted. As you are aware the second Somaliland convention will be held in the nation’s capital on September 8-10, 2006. We applaud the members of the host committee, who on top of their normal very busy schedules, admirably accepted to shoulder the demanding responsibility of organizing the 2006 Somaliland Convention. They went in earnest to raise funds from Somaliland business leaders and the Diaspora communities, selected appropriate venue that can accommodate hundreds of participants, selected and contacted speakers, formulated a three day program covering political, social, economic and environmental topics to be discussed in panels running concurrently to maximize use of time and undertook the logistics of enabling the invitees to arrive and depart in timely manner. The Committee members, who deserve all of our gratitude, are listed on the SOPRI’s web site: www.sopri.org SOPRI and the Somaliland Communities who sponsored the event extended official invitations to the following speakers, discussants and panelists. -

Somaliland in the Greater Horn of Africa

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................................1 MAPS / SOMALILAND IN THE GREATER HORN OF AFRICA ................................................................2 KEY FINDINGS............................................................................................................................................3 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................7 CHRONOLOGY / SOMALILAND’S MARCH TOWARD SELF-DECLARED INDEPENDENCE ........................................................................................................8 THE RED SHOES .........................................................................................................................10 REFUGEES THROUGH THE TURNSTILE...............................................................................................11 ETHNIC SOMALIS FLEE ETHIOPIA.................................................................................................11 TARGETED DEATH AND DESTRUCTION........................................................................................11 SEEING DOUBLE: THE NUMBERS GAME ...............................................................................12 SOMALILAND RE-EMERGES AND REFUGEES RETURN ..............................................................13 SOMALILAND: INDEPENDENT OR NOT? ................................................................................14 -

Female Genital Mutilation Survey in Somaliland

Female Genital Mutilation Survey In Somaliland At the The Edna Adan Maternity and Teaching Hospital, Hargeisa, Somaliland 2002 to 2009 By Mrs. Edna Adan Ismail, Nurse/Midwife Acknowledgements The staff and Management of the Edna Adan Maternity and Teaching Hospital wish to express appreciation for the financial support received from Norwegian Peoples Aid that provided part of the funds to undertake this survey. Sincere thanks and appreciation is expressed to the staff and students of the Edna Adan Maternity and Teaching Hospital who collected the data and recorded their findings on the Prenatal Charts following the physical examinations of the women attending the Prenatal Clinic. Sincere appreciation is expressed to the Midwives and Doctors who provided Prenatal Care to the women and who supervised the students during their rotation in the department. Sincere appreciation is expressed to the Administrative staff of the Hospital who undertook the tedious task of typing the data that had been collected by the mid- wives and student nurses and which had been recorded in the individual patient Edna Adan charts. Maternity HospitalHargeisa Sincere thanks goes also to Amal Ahmed Ali who provided much appreciated Somaliland support in editing the draft document. Tel: (00 252 828) 5999 The tabulation and analysis of the data collected could not have been carried out Tel: (0025221) 38014 without the valuable assistance of Dr. Emma Watkins of Kings College Hospital, Tel/fax (00 252 828) 5226 Denmark Hill, London, to whom sincere thanks is being expressed. -

Programme Events of HIBF 2017

Programme Events of HIBF 2017 10 Years of Hargeysa International Book Fair|22-27,July 2017 website: www.redsea-online.org | www.hargeysabookfair.com | www.kayd.org Page 1 Programme Events of HIBF 2017 Message from the Director 10 Years of Hargeysa International Book Fair It has been an immense pleasure for me to see Hargeysa In- ternational Book Fair grow into this huge success, attracting over 100,000 local, regional and international guests since its inception. Each year I look forward to seeing so many longtime friends and colleagues, as well as so many new partners—and to personal- ly welcome you to Somaliland to celebrate and promote literature, culture, arts and help establish the institutes to preserve and promote this. It’s a very exciting time for us at Redsea Cultural Foundation and in many ways, we have several milestones to mark; First of all, we are of course celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Hargeysa International Book Fair. We also have emerged over the years on the national and regional stage as a leading voice promoting literature, arts and culture and most vis- ibly to all; we have now opened the Hargeysa Cultural Centre- our new permanent location. Clearly, after a decade of steady progress, 2017 has been a watershed year—a year of achievements and reaching milestones. There are people who deserve much credit for these incredible achievements- the distinguished and highly committed members of the board of directors, staff, longtime friends, supporters and volunteers… there is no way to adequately thank them for what they help build. -

High Stakes for Somaliland's Presidential Elections

High stakes for Somaliland’s presidential elections Omar S Mahmood and Mohamed Farah The stakes are high for Somaliland’s presidential elections scheduled for 13 November 2017. After more than two years of delays, voters will finally have the chance to be heard. Given that President Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’ is stepping down, the contest will result in fresh leadership. This report sheds light on some of the pivotal political and security issues facing Somaliland at the time of these crucial elections, providing a background on the process and raising some key concerns. EAST AFRICA REPORT 15 | OCTOBER 2017 Introduction Key points The stakes are high for Somaliland’s presidential elections scheduled for The stakes for the 2017 13 November 2017. After more than two years of delays, voters will finally presidential elections are have the chance to make their voices heard. Given that President Ahmed high, and the vote is likely to Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’ is not standing for re-election, the contest will be close. result in fresh leadership regardless of the outcome. This report aims to shed While some concerns exist light on some of the pivotal political and security issues facing Somaliland at regarding the electoral the time of these crucial elections, providing a background on the process campaign and acceptance and raising some key concerns going forward. of its outcome by all sides, the successful completion This report was written in partnership by the Institute for Security Studies of a voter register is likely to (ISS) and the Academy for Peace and Development (APD), a think tank mean that the vote will be based in Hargeisa. -

Somaliland: Post-War Nation-Building and International Relations, 1991-2006

Somaliland: Post-War Nation-Building and International Relations, 1991-2006 by M. Iqbal D. Jhazbhay A Thesis Submitted in fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations, in the Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa February 2007 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of the Doctor of Philosophy in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. To the best of my knowledge, it has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at any other university. _______________________ M. Iqbal D. Jhazbhay Date: _________________________________ Supervisor, Professor John J. Stremlau Date: ii Dedication To my Parents, Grandparents, Elders and the Children of Somaliland iii Acknowledgements This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many souls. This study has been six years in the making, a multi-faceted and challenging intellectual journey, and one which would indeed not have been possible without the co-operation and encouragement of numerous individuals and institutions. Permit me to begin with my beloved wife Naseema and sons Adeeb and Faadil, who supported my nine visits to Somaliland, the Horn of Africa and tolerated my absence from them during the school holidays, where I was able to quietly work on my thesis. A debt of gratitude is also due to Professor John J Stremlau, my supervisor, for his intellectual support and consistent reminders to develop the chapters of this thesis. His significant feedback and time during difficult moments is gratefully appreciated.