Somaliland: Post-War Nation-Building and International Relations, 1991-2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Genital Mutilation: Current Practices and Perceptions in Somaliland

Global Journal of Health Education and Promotion Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 42–57 http://dx.doi.org/10.18666/GJHEP-2016-V17-I2-7101 Female Genital Mutilation: Current Practices and Perceptions in Somaliland Trista Dawn Smith, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine Cristina Redko, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine Nikki Rogers, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine Edna Adan Ismail, Edna Adan University Hospital Abstract Background: Somaliland, Africa, has the highest prevalence of female genital mutilation (FGM) in the world despite its recognition as a human rights viola- tion and decades of campaigns to eliminate it. This study establishes baseline data for FGM prevalence in Somaliland and explores changing perceptions of FGM among Somalis. Method: A descriptive study was conducted among 6,108 women at the Edna Adan University Hospital (EAUH) from 2006–2013. Data were obtained regarding FGM status and knowledge and perception to- ward the practice. Chi-square analysis was conducted to compare current and previous studies conducted at EAUH. Results: The prevalence rate of FGM among respondents was 98.4% and procedures occurred at an average age of 8.47 years. Most participants (82.20%) underwent the most severe Type III or Pharaonic FGM. The most commonly cited reason for practicing FGM was to maintain cultural and traditional values (82.9%). Continuation of the practice was supported among 83.17% of respondents, the majority of whom reported a preference for the milder Type I or II Sunna FGM (95.15%). Women who at- tended university were subjected to FGM less than were their uneducated coun- terparts. -

September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report

International Republican Institute Suite 700 1225 Eye St., NW Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 408-9450 (202) 408-9462 FAX www.iri.org International Republican Institute Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report Table of Contents Map of Somaliland……………………………………………………………………..….2 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………….....3 I. Background Information.............................................................................................…..5 II. Legal and Administrative Framework………………………………..………..……….8 III. Pre-Election Period……………. …...……………………………..…………...........12 IV. Election Day…………...…………………………………………………………….18 V. Post-Election Period and Results.…………………………………………………….27 VI. Findings and Recommendations……………………………………………………..33 VII. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..38 Appendix A: Voting Results in 2005 Presidential Elections…………………………….39 Appendix B: Voting Results in 2003 Presidential Elections…………………………….41 Appendix C: Voting Results in 2002 Local Government Elections……………………..43 Appendix D: Voting Trends……………………………………………………………..44 IRI – Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report 1 Map of Somaliland IRI – Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report 2 Executive Summary Background The International Republican Institute (IRI) has conducted programs in Somaliland since 2002 with the support of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. Department of State, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). IRI’s Somaliland -

Download Full Report

2016 Elections in Somalia - The Rise of the New Somali Women's Political Movements The Somali Institute for Development and Research Analysis (SIDRA) Garowe, Puntland State of Somalia Cell Phone: +252-907-794730 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.sidrainstitute.org This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License (CC BY-NC 4.0) Attribute to: Somali Institute for Development & Research Analysis 2016 A note of Appreciation Many Somali women freely provided their time to take part in the surveys, focus group discussions and interviews for this study and thereby helping us collect quality data that allowed us to make sound scientific analysis. Without their contributions, this study would not have reached its findings. This study was self funded by SIDRA and would not have materialized without the sacrifice of keeping aside other cost to allocate resources for this study. Finally, this study would not have come to be without the tireless efforts of SIDRA staff through the direction of Sahro Koshin, SIDRA Head of Programmes and leadership of Guled Salah, SIDRAs Executive Director. Many other people supported this study in different ways and made it a success. SIDRA whole heartedly appreciates all these people. Page | 2 2016 Elections in Somalia - The Rise of the New Somali Women's Political Movements Table of content EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................6 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION AND -

Volume 3 Demography, Data Processing and Cartography

VOLUME 3 DEMOGRAPHY, DATA PROCESSING AND CARTOGRAPHY M. Rahmi, E. Rabant, L. Cambrézy, M. Mohamed Abdi Institut de Recherche pour le Développement UNHCR – IRD October 1999 97/TF/KEN/LS/450(a$ Index MAJOR FINDINGS ...…………………………………………….……….…………….3 I-1 : Demography ...…………………………………………….……….…………….3 I-2 : Exploitation of the aerial mosaics …………………………………………..5 1 - Cartography of the refugee camps. …………………………………...……...5 2 - Estimation of the populations ………………………………………………..…6 I-3 – Conclusion : results of the integration of maps and data in a GIS … 10 II – Demography data processing ………………………………………………....13 Table 1. Number of households and family size …….....………………..….…....13 Graph 1 . Family size ..…………………………………….………………….14 Graph 2. Family size (percentage) …………………….…….……………. 15 Table 2 : Number of refugees by sex and by block …….……………...…... 15 Table 3 : number of households and family size by blocks ………………… 20 Table 4 : population by age and by sex. ……………………………...… 26 Graph 3. Pyramid of ages …………………………………………………29 Table 5 : Relationship by sex …………………………………………………38 Graph 4 : relationship …………………………………………………………39 Table 6 : Number of refugees by sex and nationality ………………….40 Table 7 : Number of refugees by sex and province of origin ………….41 Table 8 : UNHCR codes for districts and nationality ………………….43 Table 9 : Number of refugees by nationality, sex, and district of origin. ………………… 50 Table 10 : Principal districts of origin of somalian refugees (population by block and by sex). ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 69 Table 11 : Principal -

Somalia's Islamists

SOMALIA’S ISLAMISTS Africa Report N°100 – 12 December 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. ISLAMIC ACTIVISM IN SOMALI HISTORY ......................................................... 1 II. JIHADI ISLAMISM....................................................................................................... 3 A. AL-ITIHAAD AL-ISLAAMI .........................................................................................................3 1. The “Golden Age” .....................................................................................................3 2. From Da’wa to Jihad: The battle of Araare ...............................................................4 3. Towards an Islamic emirate.......................................................................................5 4. Towards an Islamic emirate – Part 2 .........................................................................7 5. A transnational network.............................................................................................7 6. From Jihad to terror: The Islamic Union of Western Somalia...................................8 7. Al-Itihaad’s twilight years .........................................................................................9 B. THE NEW JIHADIS ...............................................................................................................11 C. AL-TAKFIR WAL-HIJRA .........................................................................................................12 -

Somalia: Instability, Conflict, and Federalism

THESIS CREDIT The Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, is the international gateway for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Eight departments, associated research institutions and the Norwegian College of Veterinary Medicine in Oslo. Established in 1986, Noragric’s contribution to international development lies in the interface between research, education (Bachelor, Master and PhD program) and assignments. The Noragric Master theses are the final theses submitted by students in order to fulfil the requirements under the Noragric Master program “International Environmental Studies”, “International Development Studies” and “International Relations”. The findings in this thesis do not necessarily reflect the views of Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the author and on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation contact Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences © Abdi Ibrahim Magan, February 2016 [email protected] Noragric Department of International Environment and Development Studies P.O. Box 5003 N-1432 Ås, Norway Tel.: +47 64 96 52 00 Fax: +47 64 96 52 01 Internet: http://www.nmbu.no/noragric STUDENT’S DECLARATION I, Abdi Ibrahim Magan, declare that this thesis is a result of my research investigations and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. Signed: ______________________________ Abdi Ibrahim Magan Date: ________________________ ABSTRACT This study examines genesis of the Somali’s instability and causes of the protracted conflicts in the country. -

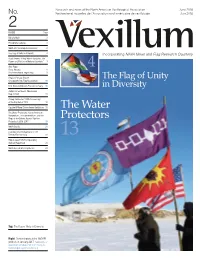

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Faithless Power As Fratricide: Is There an Alternative in Somalia?

Faithless Power as Fratricide: Is there an Alternative in Somalia? Abdi Ismail Samatar I. The Meaning of Faith Mohamed Suliman’s lovely and famous song for the Eid is not only suggestive of the joys of the past but reminisces about the great values that the Somali people shared and which served them well during test- ing times of yesteryear. Here is a line from the song: Hadba kii arrin keena Ka kalee aqbalaaya Ilaahii ina siiyay isagaa ku abaal leh Simply put, this line and the spirit of the whole song echo Somalis’ traditional acumen to generate timely ideas and the competence to lis- ten and heed productive compromises. These attributes that nurtured their collective best interests have been on the wane for three decades and are now in peril or even to perish for eternity. As a result, much despair is visible in the Somali landscape. Yet it is worth remembering that there is no inevitability about the extension of the present despon- dency into the future as long as civic-minded Somalis are resolute and remain wedded to their compatriots’ well-being and cardinal values. The concept of Faith has triple meanings in the context of this brief essay (Figure 1). First, it means devotion to the Creator and the straight path of Islam. This is clear from the core principles of Islam (not as defined by sectarian ideologues but by the Qur’an and the Haddith), one of which is imaan. Second, Faith enshrines self-reliance and the effort to pull oneself up by the bootstraps as well as attend to the needs 63 Bildhaan Vol. -

Security Council Distr.: General 18 February 2005

United Nations S/2005/89 Security Council Distr.: General 18 February 2005 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Somalia I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to the statement of the President of the Security Council of 31 October 2001 (S/PRST/2001/30), in which the Council requested me to submit reports on a quarterly basis on the situation in Somalia. The report focuses on developments regarding the national reconciliation process in Somalia since my previous report, of 8 October 2004 (S/2004/804). It also provides an update on the security situation as well as the humanitarian and development activities of United Nations programmes and agencies in Somalia. II. The formation of the Transitional Federal Government 2. The Somali National Reconciliation Conference concluded on 14 October 2004 with the swearing-in of Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed as the President of Somalia. He was elected by the members of the Transitional Federal Parliament of Somalia on 10 October 2004 after three rounds of voting. In the final round, Colonel Yusuf obtained 189 votes while the runner-up candidate, Abdullahi Ahmed Addow, obtained 79 votes. Mr. Addow accepted the outcome and pledged to cooperate with the President. Prior to the vote, all 26 presidential candidates signed a declaration to support the elected President and to demobilize their militias. 3. On 3 November, President Yusuf appointed Ali Mohammed Gedi, a veterinarian and member of the Hawiye clan, predominant in Mogadishu, as Prime Minister of the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia. 4. During the first week of December, Prime Minister Gedi announced the appointment of some 73 Ministers, Ministers of State and Assistant Ministers. -

1 MINISTRY of EDUCATION & SCIENCE REPUBLIC of SOMALILAND Fifth Draft GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP for EDUCATION PROGRAM 2018-2021 Nove

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION & SCIENCE REPUBLIC OF SOMALILAND Fifth Draft GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP FOR EDUCATION PROGRAM 2018-2021 November, 2017 1 ACRONYMS AAGR Annual Average Growth Rate ABE Alternative Basic Education ADRA Adventist Development and Relief Agency AET Africa Education Trust CA Coordinating Agency CEC Community Education Committee CRM Complaint Response Mechanism DEO District Education Officer DFID Department For International Development (UK) ECE Early Childhood Education EDT Education Development Trust EFPT EMIS Focal Point Teacher ERGA Early Grade Reading Assessment EiE Education in Emergencies EMIS Education Management Information System ESA Education Sector Analysis ESPIG Education Sector Plan Implementation Grant ESSP Education Sector Strategic Plan ESC Education Sector Committee EU European Union GA Grant Agent GDP Gross Domestic Product GER Gross Enrolment Rate GFS Girl Friendly Space GPE Global Partnership for Education GPI Gender Parity Index IDP Internally Displaced People INGO International Non-Governmental Organization IPTT Indicator Performance Tracking Table IQS Integrated Quranic Schools JRES Joint Education Sector Review KRT Key Resource Teacher MEAL Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning MLA Measuring Learning Achievement MOES Ministry of Education & Science MOERA Ministry of Endowment and Religious Affairs MOH Ministry of Health MoU Memorandum of Understanding M&E Monitoring and Evaluation NDP National Development Plan NFE None Formal Education NGO Non-Governmental Organization NRC Norwegian Refugee -

Intellectualism Amid Ethnocentrism: Mukhtar and the 4.5 Factor

Intellectualism amid Ethnocentrism: Mukhtar and the 4.5 Factor Mohamed A. Eno and Omar A. Eno I. Background The prolonged, two-year reconciliation conference held in Kenya and the resulting interim administration, implemented under the dominant tutelage of Ethiopia, are generally considered to have failed to live up to the expectations of the Somali people. The state structure was built on the foundation of a clan power segregation system known as 4.5 (four-point-five). This means the separation of the Somali people into four clans that are equal and, as such, pure Somali, against an amalga- mation of various clans and communities that are unequal to the first group and, hence, considered “impure” or less Somali. The lumping together of all the latter communities is regarded as equivalent only to a half of the share of a clan. In spite of the inherent segregation and marginalization, some schol- ars of Somali society, like historian Mohamed H. Mukhtar, believe that the apartheid-like 4.5 system is an “important accomplishment.”1 In a book chapter titled “Somali Reconciliation Conferences: The Unbeaten Track,” Mukhtar chronicles this episode as one of various “success sto- ries”2 that have emerged from the Sodere factional meeting of 1997. As the historian posits it, this could be called an achievement, particularly considering the fact that “for the first time Somali clans agreed about their relative size, power and territorial rights.”3 Then the professor emphasizes that, “the conference also recognized another segment of the Somali society which included minority groups not identified with one of the above clans, i.e., the Banadiris and the Somali Bantus, just to 137 Bildhaan Vol. -

Millions of Civilians Have Been Killed in the Flames of War... But

VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 131 • 2003 “Millions of civilians have been killed in the flames of war... But there is hope too… in places like Sierra Leone, Angola and in the Horn of Africa.” —High Commissioner RUUD LUBBERS at a CrossroadsAfrica N°131 - 2003 Editor: Ray Wilkinson French editor: Mounira Skandrani Contributors: Millicent Mutuli, Astrid Van Genderen Stort, Delphine Marie, Peter Kessler, Panos Moumtzis Editorial assistant: UNHCR/M. CAVINATO/DP/BDI•2003 2 EDITORIAL Virginia Zekrya Africa is at another Africa slips deeper into misery as the world Photo department: crossroads. There is Suzy Hopper, plenty of good news as focuses on Iraq. Anne Kellner 12 hundreds of thousands of Design: persons returned to Sierra Vincent Winter Associés Leone, Angola, Burundi 4 AFRICAN IMAGES Production: (pictured) and the Horn of Françoise Jaccoud Africa. But wars continued in A pictorial on the African continent. Photo engraving: Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Aloha Scan - Geneva other areas, making it a very Distribution: mixed picture for the 12 COVER STORY John O’Connor, Frédéric Tissot continent. In an era of short wars and limited casualties, Maps: events in Africa are almost incomprehensible. UNHCR Mapping Unit By Ray Wilkinson Historical documents UNHCR archives Africa at a glance A brief look at the continent. Refugees is published by the Media Relations and Public Information Service of the United Nations High Map Commissioner for Refugees. The 17 opinions expressed by contributors Refugee and internally displaced are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do UNHCR/P. KESSLER/DP/IRQ•2003 populations. not imply the expression of any With the war in Iraq Military opinion or recognition on the part of officially over, UNHCR concerning the legal status UNHCR has turned its Refugee camps are centers for of a territory or of its authorities.