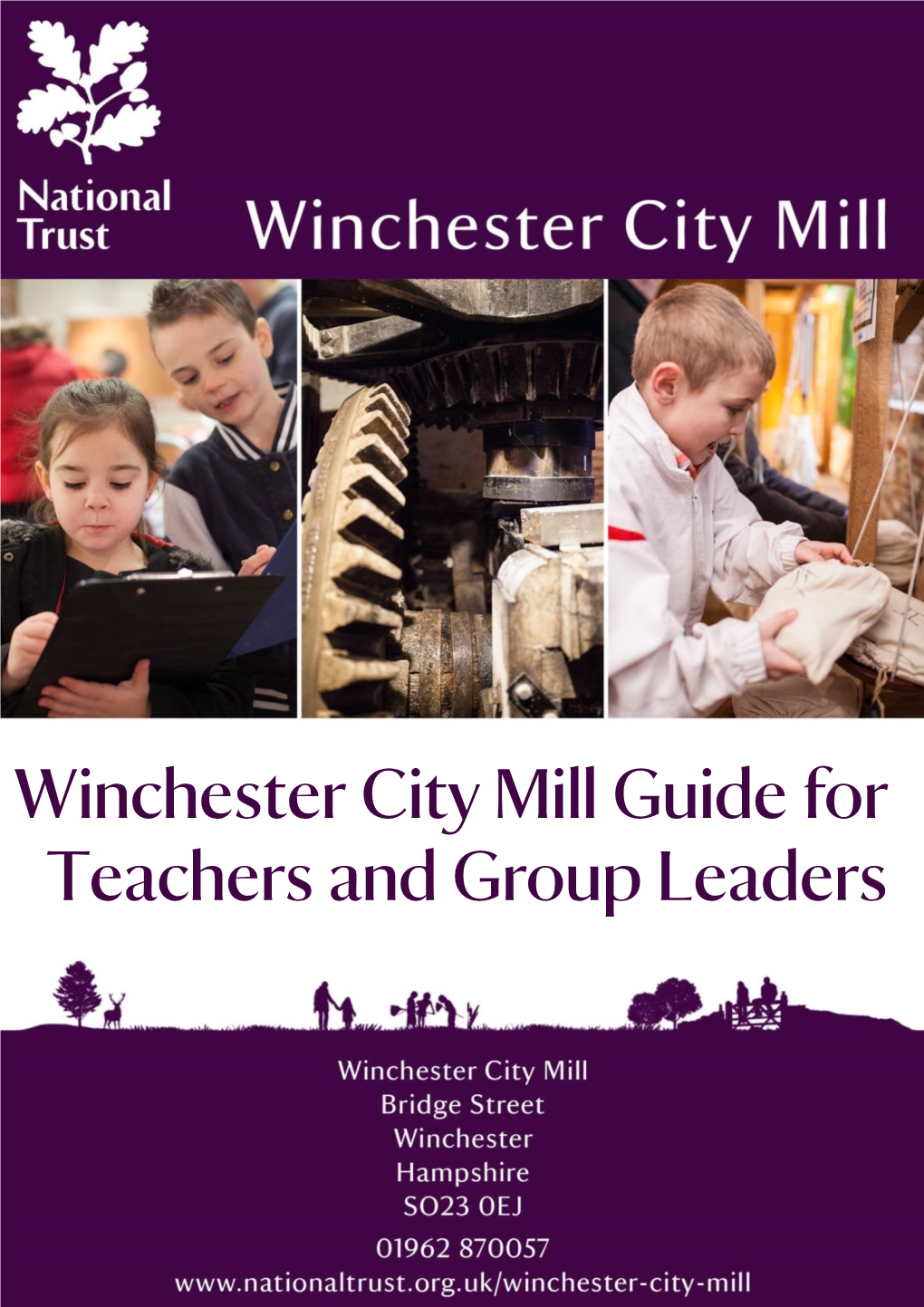

Winchester City Mill Guide for Teachers and Group Leaders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developments in Permanent Stainless Steel Cathodes Within the Copper Industry

DEVELOPMENTS IN PERMANENT STAINLESS STEEL CATHODES WITHIN THE COPPER INDUSTRY K.L. Eastwood and G.W. Whebell Xstrata Technology Hunter Street Townsville, Australia 4811 [email protected] ABSTRACT The ISA PROCESS™ cathode plate is characterised by its copper coated suspension bar, coupled with a blade employing austenitic stainless steel alloy 316L. The blade material has become the mainstay of the technology and has been closely copied by competing cathode designs. Improvement to the cathode plate design remains a key area for research, and ongoing developments by Xstrata Technology’s ISA PROCESS™ have recently been commercialised. Two such developments are the ISA Cathode BR™ and ISA 2000 AB Cathode. The ISA BR cathode is a lower resistance cathode that has proven to enhance operating efficiencies. The AB cathode was designed to improve stripping inefficiencies in the ISA 2000 technology. These developments have now had time to mature and their long term performance will be discussed. Rising material costs and the desire to extend the operating boundaries of the standard 316L cathode plate has triggered a number of significant advances. These involve the use of different stainless steels as alternatives in some operational situations. The technical aspects and results of commercial trials on this development will also be discussed in this paper. INTRODUCTION The introduction of permanent stainless steel cathode technology was pioneered in the copper industry by IJ Perry and colleagues in 1978, with the introduction of the ISA PROCESSTM in the Townsville Copper Refinery, Perry [1]. While a number of parallel processes have emerged since its introduction, ISA Process Technology (IPT) has continued to be the mainstay electrolytic copper process with consistent improvements and superior operational performance. -

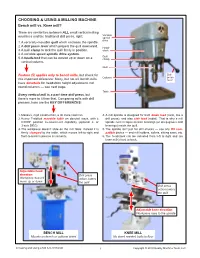

Choosing & Using a Milling Machine

CHOOSING & USING A MILLING MACHINE Bench mill vs. Knee mill? There are similarities between ALL small vertical milling Variable machines and the traditional drill press, right: speed drive 1. A vertically-movable quill which encloses the spindle. 2. A drill press lever which propels the quill downward. Head- 3. A quill clamp to lock the quill firmly in position. stock 4. A variable-speed spindle drive system. Quill 5. A headstock that can be moved up or down on a clamp vertical column. Quill Feature (5) applies only to bench mills, but check for Drill Column press this important difference: Many, but not all, bench mills lever have dovetails for headstock height adjustment, not round columns — see next page. Table Every vertical mill is a part-time drill press, but there’s more to it than that. Comparing mills with drill presses, here are the KEY DIFFERENCES: 1. Massive, rigid construction, a lot more cast iron. 4. A mill spindle is designed for both down load (axial, like a 2. Heavy T-slotted movable table on dovetail ways, with ± drill press), and also side load (radial). That is why a mill 0.0005″ position measurement capability (optional 2- or spindle runs in tapered roller bearings (or deep-groove ball 3-axis DRO). bearings) inside the quill. 3. The workpiece doesn’t slide on the mill table: instead it is 5. The spindle isn’t just for drill chucks — use any R8 com- firmly clamped to the table, which moves left-to-right and patible device — end mill holders, collets, slitting saws, etc. -

Millstones for Medieval Manors

Millstones for Medieval Manors By DAVID L FARMER Abstract Demesne mills in medieval England obtained their millstones from many sources on the continent, in Wales, and in England. The most prized were French stones, usually fetched by cart from Southampton or ferried by river from London. Transport costs were low. Millstone prices generally doubled between the early thirteenth century and the Black Death, and doubled again in the later fourteenth century. With milling less profitable, many mills in the fourteenth century changed from French stones to the cheaper Welsh and Peak District stones, which Thames valley manors were able to buy in a large number of Midland towns and villages. Some successful south coast mills continued to buy French stones even in the fifteenth century. ICHARD Holt recently reminded us millstones were bought in a port or other that mills were at the forefront of town; demesne mills bought relatively R medieval technology and argued few at quarries. The most prized stones persuasively that windmills may have been came from France, from the Seine basin invented in late twelfth-century England.' east of Paris. In later years these were built But whether powered by water, wind, or up from segments of quartzite embedded animals, the essential of the grain mill was in plaster of Paris, held together with iron its massive millstones, up to sixteen 'hands' hoops. There is no archaeological evidence across, and for the best stones medieval that such composite stones were imported England relied on imports from the Euro- before the seventeenth century, but the pean continent. -

THE NEW KEENE ROCK CRUSHERS ROLLER MILL Produc T Report

THE NEW KEENE Produc t ROCK CRUSHERS Report AND COMBINATION By AU Testing Laboratories ROLLER MILL Base Mount Trailer Mounted Electric Driven dered a competitive price on the mar- testing site because it contained an Keene Engineering has brought into ket today. THE COST IS LESS THAN abundance of fractured quartz rock view, a new ROCK CRUSHER that HALF. containing gold and silver. The rock has brought the mining industry to its When AU Testing Laboratories was also extremely harder than com- feet. A new combination rock crusher first agreed to make an evaluation on mon type ore of this nature and and roller mill that has the capacity of this product, we were needless to say should provide a good test for any crushing a four by six rock into "ultra skeptical about the manufacturer's type crushing equipment. fine powder," in one single, quick and claims, but were again impressed Although the unit weighed over efficient operation. They have com- with the performance of this beauty. 700 pounds it was surprisingly easy bined two separate processes of rock We learned that Keene had been in to tote around. We moved many crushing into a single machine. the process of engineering and test- times to different locations on the The first stage is a jaw crusher ing this unit for over 10 years and this mine site with relative ease. We that crushes aggregate to one quarter unit has evolved from some twenty understood that this machine could of an inch, that can be adjustable to previous prototypes. be provided on either a permanent larger or smaller size and the second We loaded the unit with its base or trailer mounted. -

Milling Studies in an Impact Crusher I: Kinetics Modelling Based on Population Balance Modelling

minerals Article Milling Studies in an Impact Crusher I: Kinetics Modelling Based on Population Balance Modelling Ngonidzashe Chimwani 1,* and Murray M. Bwalya 2 1 Institute of the Development of Energy for African Sustainability (IDEAS), Florida Campus, University of South Africa (UNISA), Private Bag X6, Johannesburg 1710, South Africa 2 School of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2050, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-731838174 Abstract: A number of experiments were conducted on a laboratory batch impact crusher to investi- gate the effects of particle size and impeller speed on grinding rate and product size distribution. The experiments involved feeding a fixed mass of particles through a funnel into the crusher up to four times, and monitoring the grinding achieved with each pass. The duration of each pass was approximately 20 s; thus, this amounted to a total time of 1 min and 20 s of grinding for four passes. The population balance model (PBM) was then used to describe the breakage process, and its effectiveness as a tool for describing the breakage process in the vertical impact crusher is assessed. It was observed that low impeller speeds require longer crushing time to break the particles significantly whilst for higher speeds, longer crushing time is not desirable as grinding rate sharply decreases as the crushing time increases, hence the process becomes inefficient. Results also showed that larger particle sizes require shorter breakage time whilst smaller feed particles require longer breakage time. Keywords: impact crusher; comminution; milling parameters; population balance mode Citation: Chimwani, N.; Bwalya, M.M. -

Avoiding Slopping in Top-Blown BOS Vessels

ISSN: 1402-1757 ISBN 978-91-7439-XXX-X Se i listan och fyll i siffror där kryssen är LICENTIATE T H E SI S Department of Chemical Engineering and Geosciences Division of Extractive Metallurgy Mats Brämming Avoiding Slopping in Top-Blown BOS Vessels BOS Top-Blown Slopping in Mats Brämming Avoiding ISSN: 1402-1757 ISBN 978-91-7439-173-2 Avoiding Slopping Luleå University of Technology 2010 in Top-Blown BOS Vessels Mats Brämming Avoiding Slopping in Top-blown BOS Vessels Mats Brämming Licentiate Thesis Luleå University of Technology Department of Chemical Engineering and Geosciences Division of Extractive Metallurgy SE-971 87 Luleå Sweden 2010 Printed by Universitetstryckeriet, Luleå 2010 ISSN: 1402-1757 ISBN 978-91-7439-173-2 Luleå 2010 www.ltu.se To my fellow researchers: “Half a league half a league, Half a league onward, All in the valley of Death Rode the six hundred: 'Forward, the Light Brigade! Charge for the guns' he said: Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred. 'Forward, the Light Brigade!' Was there a man dismay'd ? Not tho' the soldier knew Some one had blunder'd: Theirs not to make reply, Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do & die, Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred.” opening verses of the poem “The Charge Of The Light Brigade” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson PREFACE Slopping* is the technical term used in steelmaking to describe the event when the slag foam cannot be contained within the process vessel, but is forced out through its opening. This phenomenon is especially frequent in a top-blown Basic Oxygen Steelmaking (BOS) vessel, i.e. -

Working with Watermills" Lesson Explores How Watermills Have Helped Harness Energy from Water Through the Ages

IEEE Lesson Plan: W or k i ng w i t h W at e r m i ll s Explore other TryEngineering lessons at www.tryengineering.org Lesson Focus Lesson focuses on how watermills generate power. Student teams design and build a working watermill out of everyday products and test their design in a basin. Student watermills must be able to sustain three minutes of rotation. As an extension activity, older students may design a gear system that is powered by the watermill. Students then evaluate the effectiveness of their watermill and those of other teams, and present their findings to the class. Lesson Synopsis The "Working with Watermills" lesson explores how watermills have helped harness energy from water through the ages. Students work in teams of "engineers" to design and build their own watermill out of everyday items. They test their watermill, evaluate their results, and present to the class. A g e L e v e l s 8-18. Objectives Learn about engineering design. Learn about planning and construction. Learn about teamwork and working in groups. Anticipated Learner Outcomes As a result of this activity, students should develop an understanding of: structural engineering and design problem solving teamwork Lesson Activities Students learn how watermills have been used throughout the ages to harness the power of water. Students work in teams to develop a their own watermill out of everyday items, then test their watermill, evaluate their own watermills and those of other students, and present their findings to the class. Working with Watermills Provided by IEEE as part of TryEngineering www.tryengineering.org © 2018 IEEE – All rights reserved. -

Hydropower Vision Chapter 2

Chapter 2: State of Hydropower in the United States Hydropower A New Chapter for America’s Renewable Electricity Source STATE OF HYDROPOWER 2 in the United States Photo from 65681751. Illustration by Joshua Bauer/NREL 70 2 Overview OVERVIEW Hydropower is the primary source of renewable energy generation in the United States, delivering 48% of total renewable electricity sector generation in 2015, and roughly 62% of total cumulative renewable generation over the past decade (2006-2015) [1]. The approximately 101 gigawatts1 (GW) of hydropower capacity installed as of 2014 included ~79.6 GW from hydropower gener ation2 facilities and ~21.6 GW from pumped storage hydro- power3 facilities [2]. Reliable generation and grid support services from hydropower help meet the nation’s require- ments for the electrical bulk power system, and hydro- power pro vides a long-term, renewable source of energy that is essentially free of hazardous waste and is low in carbon emissions. Hydropower also supports national energy security, as its fuel supply is largely domestic. % 48 HYDROPOWER PUMPED CAPACITY STORAGE OF TOTAL CAPACITY RENEWABLE GENERATION Hydropower is the largest renewable energy resource in the United States and has been an esta blished, reliable contributor to the nation’s supply of elec tricity for more than 100 years. In the early 20th century, the environmental conse- quences of hydropower were not well characterized, in part because national priorities were focused on economic development and national defense. By the latter half of the 20th century, however, there was greater awareness of the environmental impacts of dams, reservoirs, and hydropower operations. -

Xstrata Technology Update Edition 14 – April 2013 Our First Quarter Century

xstrata technology update Edition 14 – April 2013 Our First Quarter Century Of course XT’s roots started well before this, with generations of engineers and unusual one – most companies keep their technology developments as a solutions, and driven both by a need to survive with increasingly complex think that technologies only become demanded and developed practical and is why the User Group concept is central real technology advances start with robust improvements – from permanent to our technologies – assembling a real problems – necessity is always the stainless steel cathode technology for bigger diverse group of operators with a mother of invention – and prosper only with the perseverance and the ongoing radically improved grinding technology, which then spawned a new atmospheric long investment horizons and high capital We see the challenges facing industry risk, the minerals industry typically takes and have some exciting concepts to The technologies were different but track record of turning concepts into decade to go from original concept we have powerful networks in our user through to laboratory, demonstration groups – people from diverse cultures and concepts to solve real problems in our companies bound by a common goal of engineers to make it even more reliable Xstrata Technology Contacts Email Web or follow Xstrata Technology on AUSTRALIA SOUTH AFRICA CANADA CHILE EUROPE Brisbane Townsville Johannesburg Santiago London T T T T T T F F F F © Copyright 2013 Xstrata Technology Pty Ltd All -

Maximum Value Minerals Processing

⎪ Materials handling ⎪ Maximum value minerals processing MechChem Africa talks to Cedric Walstra, Glencore Technology’s Africa business development manager, who paints a broad picture of the high-recovery, high- efficiency processing equipment on offer from the technology side of Glencore’s business. joined Xstrata Technology about cost of grinding circuits. Intense grinding ten years ago, while Glencore was a is achieved using inert ceramic grinding “ shareholder, but Glencore took us over media that leads to improved metallurgical Iabout four years ago and the name performance compared with conventional was changed to Glencore Technology,” begins steel media. Walstra, adding that Glencore Technology “Anglo Platinium has some 26 IsaMills develops, markets and supports niche tech- currently in operation. These are horizontal nologies for the global mining and minerals fine grinding mills with cantilevered shaft and processing and metals’ extraction industries, eight grinding discs. Each mill is filled to 70 to “and not only for the mines owned by the 80% of capacity with ceramic grinding beads. Above: A Jameson flotation cell in operation at Lumwana in Zambia. The system offers the highest possible Glencore Group.” As the shaft rotates, the discs and beads cause throughput in a very small footprint, with froth washing maximising the concentrate grade in a single “Glencore Technology is a standalone attrition grinding,” Walstra explains. flotation stage. Left: IsaKidd Technology, shown here in use at the Kamoto Copper Company (KCC) in the company that partners with several tech- “Kidney shaped holes in the discs allow the DRC, is the global benchmark in copper electrowinning accounting for over 11 mtpa of copper production from over 100 licensees. -

Micro-Hydroelectric Power and the Historic Environment

Micro-Hydroelectric Power and the Historic Environment On 1st April 2015 the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England changed its common name from English Heritage to Historic England. We are now re-branding all our documents. Although this document refers to English Heritage, it is still the Commission's current advice and guidance and will in due course be re-branded as Historic England. Please see our website for up to date contact information, and further advice. We welcome feedback to help improve this document, which will be periodically revised. Please email comments to [email protected] We are the government's expert advisory service for England's historic environment. We give constructive advice to local authorities, owners and the public. We champion historic places helping people to understand, value and care for them, now and for the future. HistoricEngland.org.uk/advice Micro-Hydroelectric Power and the Historic Environment PLANNING AND HISTORIC BUILDING LEGISLATION Installing a renewable power generation scheme can be both financially and environmentally rewarding. It is important to ensure that the historic significance of any feature that may be affected by the scheme is fully understood before physical work commences. In deciding how best to incorporate a low-carbon or renewable technology, the principle of minimum intervention and reversibility should be adopted whenever and wherever possible. English Heritage is the government’s adviser on the historic environment. Central to our role is the advice we give to local planning authorities and government departments on development proposals affecting listed and traditional buildings, conservation sites and areas, terrestrial and underwater archaeological sites, designed landscapes and historical aspects of the landscape as a whole. -

Isakidd™ – 2020 Compendium of Technical Papers Contents

2020 Compendium of Technical Papers Long the benchmark in the industry, IsaKidd™ accounts for over 13.6 mtpa of copper production from over 116 licensees world wide, including Glencore’s own operations. We provide clients with a comprehensive range of technology, process support and core equipment to ensure long term operational and economic success.” IsaKidd™ at a Glance > IsaKidd™ Technology is focused on delivering quality products and services to its customers whilst continuously working on technical innovations and developments to address the ever changing needs of the market. > Since development and commercialisation in the early 1980s, both ISA and KIDD technologies have undergone continuous improvement and today are regarded as the benchmark technologies for high intensity copper electro-refining and electro-winning operations. > Significant advancements have been achieved with both the stainless steel cathode technology and the electrode handling equipment used in copper tankhouses. For more: [email protected] Tel +61 7 3833 8500 IsaKidd™ – 2020 Compendium of Technical Papers Contents Copper Refinery Modernisation, Mopani Copper Mines Plc, Mufulira, Zambia ................................................................................................................... 2 Mount Isa Mines Necessity Driving Innovation ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Current Distribution