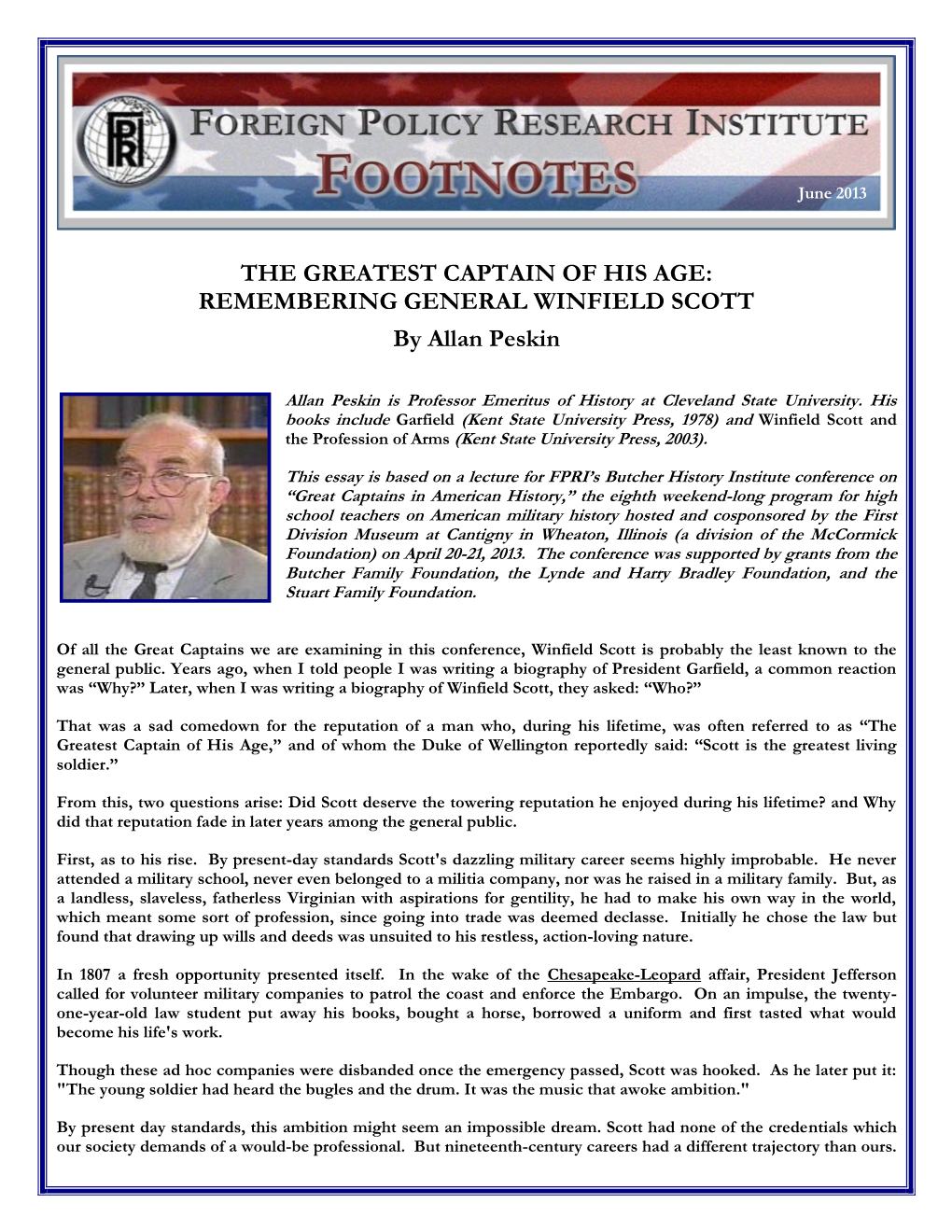

THE GREATEST CAPTAIN of HIS AGE: REMEMBERING GENERAL WINFIELD SCOTT by Allan Peskin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Wilkinson and John Brown Letters to James Morrison

James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Brown, John, 1757-1837. Creator: Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Title: James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Dates: 1808-1818 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0577 Biographical/Historical Note James Morrison (1755-1823) was born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a soldier in the Revolutionary War and served as a navy agent and officer for the Quartermaster general. In 1791 he married Esther Montgomery; reportedly they had no children. In 1792 Morrison moved to Kentucky where he became wealthy as a manufacturer and merchant of hemp. He bequeathed money for the founding of Transylvania University in Kentucky. John Brown (1757 -1837), American lawyer and statesman heavily involved with creating the State of Kentucky. James Wilkinson (1757-1825). Following the Revolutionary War, Wilkinson moved to Kentucky, where he worked to gain its statehood. In 1787 Wilkinson became a traitor and began a long-lasting relationship as a secret agent of Spain. After Thomas Jefferson purchased Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte, Wilkinson was named territorial governor of northern Louisiana. He also served as the commander in chief of the U.S. Army. Scope and Content Note This collection consists of two unrelated letters addressed to James Morrison, the first from James Wilkinson, the second is believed to be from John Brown. Index Terms Brown, John, 1757-1837. Land tenure. Letters (correspondence) Morrison, James. United States. Army. Quartermaster's Department. Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Administrative Information Custodial History Unknown. Preferred Citation [item identification], James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to John Morrison, MS 577, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia. -

The Dispute Over the Annexation of Texas and Opposition to the Mexican War Prior to Texas's Independence, the Nueces River Was R

American Studies Mr. Carlson The Dispute over the Annexation of Texas and opposition to the Mexican War Prior to Texas's independence, the Nueces River was recognized as the northern boundary of Mexico. Spain had fixed the Nueces as a border in 1816, and the United States ratified it in the 1819 treaty by which the United States had purchased Florida and renounced claims to Texas. Even following Mexico's independence from Spain, American and European cartographers fixed the Texas border at the Nueces. When Texas declared its independence, however, it claimed as its territory an additional 150 miles of land, to the Rio Grande. With the annexation of Texas in 1845, the United States adopted Texas's position and claimed the Rio Grande as the border. Mexico broke diplomatic relations with the United States and refused to recognize either the Texas annexation or the Rio Grande border. President James Polk sent a special envoy, John L. Slidell, to propose cancellation of Mexico's debt to United States citizens who had incurred damages during the Mexican Revolution, provided Mexico would formally recognize the Rio Grande boundary. Slidell was also authorized to offer the Mexican government up to $30 million for California and New Mexico. Between Slidell's arrival on December 6, 1845, and his departure in March 1846, the regime of President Jose Herrara was overthrown and a fervently nationalistic government under General Mariano Paredes seized power. Neither leader would speak to Slidell. When Paredes publicly reaffirmed Mexico's claim to all of Texas, Slidell left in a temper, convinced that Mexico should be "chastised." American Studies Mr. -

Ambition Graphic Organizer

Ambition Graphic Organizer Directions: Make a list of three examples in stories or movies of characters who were ambitious to serve the larger good and three who pursued their own self-interested ambition. Then complete the rest of the chart. Self-Sacrificing or Self-Serving Evidence Character Movie/Book/Story Ambition? (What did they do?) 1. Self-Sacrificing 2. Self-Sacrificing 3. Self-Sacrificing 1. Self-Serving 2. Self-Serving 3. Self-Serving HEROES & VILLAINS: THE QUEST FOR CIVIC VIRTUE AMBITION Aaron Burr and Ambition any historical figures, and characters in son, the commander of the U.S. Army and a se- Mfiction, have demonstrated great ambition cret double-agent in the pay of the king of Spain. and risen to become important leaders as in politics, The two met privately in Burr’s boardinghouse and the military, and civil society. Some people such as pored over maps of the West. They planned to in- Roman statesman, Cicero, George Washington, and vade and conquer Spanish territories. Martin Luther King, Jr., were interested in using The duplicitous Burr also met secretly with British their position of authority to serve the republic, minister Anthony Merry to discuss a proposal to promote justice, and advance the common good separate the Louisiana Territory and western states with a strong moral vision. Others, such as Julius from the Union, and form an independent western Caesar, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Adolf Hitler were confederacy. Though he feared “the profligacy of often swept up in their ambitions to serve their own Mr. Burr’s character,” Merry was intrigued by the needs of seizing power and keeping it, personal proposal since the British sought the failure of the glory, and their own self-interest. -

Slaveholding Presidents Gleaves Whitney Grand Valley State University

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Ask Gleaves Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies 7-19-2006 Slaveholding Presidents Gleaves Whitney Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ask_gleaves Recommended Citation Whitney, Gleaves, "Slaveholding Presidents" (2006). Ask Gleaves. Paper 30. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ask_gleaves/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ask Gleaves by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Slaveholding Presidents - Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies - Grand Valley State... Page 1 of 1 Slaveholding Presidents How many of our presidents owned slaves? There are two ways of interpreting your question. Either: How many presidents owned slaves at some point in their lives? Or: How many presidents owned slaves while serving as chief executive? Many books get the answers to these questions wrong, and when I speak on the presidents and ask these two questions, audiences invariably low-ball the answer to both. It comes as a shock to most Americans' sensibilities that more than one in four U.S. presidents were slaveholder: 12 owned slaves at some point in their lives. Significantly, 8 presidents owned slaves while living in the Executive Mansion. Put another way, for 50 of the first 60 years of the new republic, the president was a slaveholder. Following is the number of slaves each of the 12 slaveholding presidents owned. (CAPS indicate the George Washington, depicted here at president owned slaves while serving as the chief executive):[1] his Mount Vernon estate, owned between 250 and 350 slaves. -

Book Reviews from Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: a Journal of The

Book Reviews 425 From Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: A Journal of the Wayne Campaign, July 28-September 14, 1794, Edited by Dwight L. Smith. Volume XVI, Number 3, Indiana Historical Society PublicaCions. (Indianapolis : Indiana Historical Society, 1952, pp. 95. Index. $1.00.) With the publication of this journal dealing with the Wayne campaign the historian is furnished with additional documentary evidence concerning the intrigue of one of the most ambitious and treasonable figures in American history, General James Wilkinson. Despite the fact that the writer of this journal remains anonymous, his outspoken support of the wily Wilkinson is significant in that it substantiates in an intimate fashion the machinations of Wilkinson against his immediate military superior, General Anthony Wayne. The reader cannot help but be impressed with this evidence of the great influence of Wilkinson’s personal magnetism, which simultaneously won for him a pension from the Span- ish monarch and the support of many Americans a few years prior to the launching of this campaign. The journal covers the crucial days from July 28 to September 14, 1794, during which time Wayne and his men advanced from Fort Greene Ville to a place in the Maumee Valley known as Fallen Timbers, where the Indian Confed- eration was dealt a body blow. Included in it are many de- tails such as supply problems, geographical features, and personalities. Unfortunately, the pronounced pro-Wilkinson bias of the writer inclines the reader to exercise mental reservations in accepting much of the information even though it be of a purely factual nature. In a brief but able introduction, Smith sets the stage for this account of this military expedition of General Wayne against the Indians of the Old Northwest. -

Lesson Guide

C a p t i o n e d M e d i a P r o g r a m VOICE (800) 237-6213 TTY (800) 237-6819 FAX (800) 538-5636 E-MAIL [email protected] WEB www.captionedmedia.org #12136 W. H. HARRISON, TYLER, POLK, & TAYLOR NEW DIMENSION MEDIA/QUESTAR, 2003 Grade Level: 3–8 12 Minutes CAPTIONED MEDIA PROGRAM RELATED RESOURCES #12119 A. JOHNSON, GRANT, & HAYES #12120 ABRAHAM LINCOLN #12121 ACTIVE CITIZENSHIP: MAKING A DIFFERENCE #12122 CARTER, REAGAN, & G.H. BUSH #12123 CLEVELAND, MCKINLEY, & THEODORE ROOSEVELT #12124 CLINTON & G.W. BUSH #12125 FILLMORE, PIERCE, & BUCHANAN #12126 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT #12127 GARFIELD, ARTHUR, CLEVELAND, & B. HARRISON #12128 GEORGE WASHINGTON #12129 J.Q. ADAMS, JACKSON, & VAN BUREN #12130 JOHN ADAMS & THOMAS JEFFERSON #12131 L.B. JOHNSON, NIXON, & FORD #12132 MADISON & MONROE #12133 TAFT, WILSON, HARDING, COOLIDGE, & HOOVER #12134 THE MAKING OF AMERICA'S PRESIDENCY #12135 TRUMAN, EISENHOWER, & KENNEDY Funding for the Captioned Media Program is provided by the U.S. Department of Education New Dimension Media TEACHER’S GUIDE Grades 5 to 12 W.H. Harrison, Tyler, Polk & Taylor Our Presidents in America’s History Series Subject Area: Social Studies, U.S. History Synopsis: Chronicles the presidencies of William H. Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor. Focuses on westward expansion and the growing tensions between Northern and Southern states over slavery. Discusses the dishonest campaign that won Harrison the presidency; the controversial actions of Tyler; the expansion of American borders during the Polk presidency, and the controversy over extending slavery to new territories in Taylor’s term. -

The Foreign Service Journal, October 1978

& x '«If* ■ "• i«. *' ■ V' *%>■ ■■ . ■■' ■ y -4 I The American Intellectual in Foreign Affairs by Charles Maechling, Jr. The Next Problem in Arms Control by Roger A. Beaumont What Is Public Diplomacy? by Kenneth Wimmel FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL OCTOBER 1978 75 CENTS Feel at home with security... AFSA Group Accident Insurance for Loss of Life, Limb or Sight. “Make yourself at home.” How often is heard that warm invitation to share the comfort and security of a friend's home. And though the surroundings may be unfamiliar, they somehow seem less foreign and more secure because your host is there to help protect you. Home is where the security is! Similarly, AFSA Group Accident Insurance for loss of life, limb or eye¬ sight provides that added security to make many of our members feel at home anywhere they happen to be. This AFSA program provides financial protection against accidental loss of life, limb or eyesight 24 hours a day, the year round, anywhere in the world. You and your family can be covered ACT NOW! Get all the facts about benefits, whether you’re traveling by car, taxi, train, rates and exceptions .on AFSA Group boat, bus, subway and even as passengers Accident Protection for loss of life, limb or on most commercial, private and military eyesight—direct by mail! No agent will call. planes you’d normally travel in. Just complete the coupon below and mail Moreover, protection is provided during today. No obligation. So don’t delay on a business, pleasure and just plain day-to-day plan that can mean added security for you activities at home and abroad. -

Occasional Bulletins HENRY BURBECK

No. 3 The Papers of Henry Burbeck Clements Library October 2014 OccasionalTHE PAPERS OF HENRY Bulletins BURBECK hen Henry Burbeck fought at the Battle of Bunker Hill Schopieray details, other caches of Burbeck material went to the on June 17, 1775, he had just celebrated his twenty-first Fraunces Tavern Museum in New York, the New London County Wbirthday. The son of a British colonial official who was (Connecticut) Historical Society , the Burton Historical Collection at second in command of Old Castle William in Boston Harbor, young the Detroit Public Library, the United States Military Academy, the Henry could not have foreseen that he would spend the next four New York Public Library, the Newberry Library, and to dealers and decades in ded- collectors. But it icated service to wasn’t until 2011 a new American that the majority nation. In of Burbeck’s those forty manuscripts went years, at half up for sale at a dozen Heritage Auctions Revolutionary in Los Angeles. War battles, at We learned about West Point, at that a day before forts and out- the auction, and posts up and our hurried down the west- run at the papers ern frontier, at fell short. Three the court mar- years later, with tial of James the new Norton Wilkinson, and Strange as Chief of the Townshend Fund In 1790 Henry Burbeck established Fort St. Tammany on the St. Mary’s River, the boundary Artillery Corps providing much- between Georgia and Spanish Florida. He commanded there until 1792. Surgeon’s Mate Nathan from 1802 to needed support Hayward presented Burbeck with this view of the finished fort. -

1 Failed Filibusters: the Kemper Rebellion, the Burr Conspiracy And

Failed Filibusters: The Kemper Rebellion, the Burr Conspiracy and Early American Expansion Francis D. Cogliano In January 1803 the Congressional committee which considered the appropriation for the Louisiana Purchase observed baldly, “it must be seen that the possession of New Orleans and the Floridas will not only be required for the convenience of the United States, but will be demanded by their most imperious necessities.”1 The United States claimed that West Florida, which stretched south of the 31st parallel from the Mississippi River in the west to the Apalachicola River in the east (roughly the modern state of Louisiana east of the Mississippi, and the Gulf coasts of Mississippi and Alabama, and the western portion of the Florida panhandle) was included in the Louisiana Purchase, a claim denied by the Spanish. The American claim was spurious but the intent behind it was clear. The United States desired control of West Florida so that the residents of the Mississippi Territory could have access to the Gulf of Mexico. Since the American Revolution the region had been settled by Spaniards, French creoles and Anglo-American loyalists. Beginning in the 1790s thousands of emigrants from the United States migrated to the territory, attracted by a generous system of Spanish land grants. An 1803 American government report described the population around Baton Rouge as “composed partly of Acadians, a very few French, and great majority of Americans.” During the first decade of the nineteenth century West Florida became increasingly unstable. In addition to lawful migrants, the region attracted lawless adventurers, including deserters from the United States army and navy, many of whom fled from the nearby territories of Louisiana and Mississippi.2 1 Annals of Congress, 7th Cong. -

November 1, 2017-Thursday, November 30, 2017 Time Zone: (UTC-05:00) Eastern Time (US & Ca Nada) (Adjusted for Daylight Saving Time)

, Kania, Adriana (OST) Subject SecretaryScheduler (OST) Calendar SecretaryScheduler (OST) Calendar SecretarySched [email protected] Wednesday, November 1, 2017-Thursday, November 30, 2017 Time zone: (UTC-05:00) Eastern Time (US & Ca nada) (Adjusted for Daylight Saving Time) November 2017 Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 1 2 3 4 ~ §_ 1 ~ ~ 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 1? 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 • Busy ~Tentative 0 Free • Out of Office :J Working Elsewhere D Outside of Working Hours - November 2017 Wed, Nov l D All Day (b) (6) 0 Before 7:30AM Free 7:30AM -8:00AM Private Appoint ment •0 8:00 AM- 8:15 AM Free 8:15 AM -8:30AM Residence/DOT • 8:30 AM -9:00AM Sr Staff Meeting • Secretary's Conference Room D 9:00AM-9:30 AM Free 9:30AM -10:00 AM Private Appointment •D 10:00 AM - 10:20 AM Free 10:20 AM -10:40 AM DOT/WH •0 10:40 AM- 11:00 AM Free 11:00 AM -11:30 AM Briefing on Device Secur it~ wLo POTUS •0 11:30 AM- 11:56, AM Free 1 11:56 AM -12:55 PM Cabinet Meeting- PO I US (alll:3Uam DI:LAYI:O .l5 • minutes WH Cabinet Room SecretaryScheduler (OST) 12:55 PM-1:10PM WH/DOT • 1:10PM-2:10PM Lunch with Brian Gallagher, United Way_ Worldwide • Secretary's Office SecretaryScheduler (05T) D 2:10PM - 2:30PM Free 2:30PM - 3:50PM ELD Briefing • Secretary's Conference Room SecretaryScheduler (OST) D 3:50PM - 4:00PM Free 4:00 PM - 4:30PM FHWA Emergency_ Relief Program Briefing • Secretary's Conference Room SecretaryScheduler (OST) D 4:30PM-5:00PM Free D 5:00PM - 5:50PM Free 5:50PM - 6:00PM Call with Dr. -

Trailing Clouds of Glory: Zachary Taylor's Mexican War Campaign and His Emerging Civil Leaders

Civil War Book Review Summer 2010 Article 14 Trailing Clouds of Glory: Zachary Taylor's Mexican War Campaign and His Emerging Civil Leaders Kevin Dougherty Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Dougherty, Kevin (2010) "Trailing Clouds of Glory: Zachary Taylor's Mexican War Campaign and His Emerging Civil Leaders," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 . Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol12/iss3/14 Dougherty: Trailing Clouds of Glory: Zachary Taylor's Mexican War Campaign a Review Dougherty, Kevin Summer 2010 Lewis, Felice Flanery Trailing Clouds of Glory: Zachary Taylor’s Mexican War Campaign and His Emerging Civil Leaders. University of Alabama Press, $35.00 ISBN 978-0-8173-1678-5 Looking at the Pre-Civil War Proving Ground Readers have benefited from several recent treatments of the Mexican War, including A Gallant Little Army (2007), Timothy Johnson’s well-received chronicle of Winfield Scott’s Mexico City Campaign. However, if the Mexican War has been largely overshadowed by other wars, Felice Flanery Lewis complains, “Modern historians, in emphasizing [Winfield] Scott’s brilliance, have also tended to dismiss the significance of Taylor’s campaign" (228). She sets out to correct this negligence in Trailing Clouds of Glory: Zachary Taylor’s Mexican War Campaign and His Emerging Civil Leaders. Lewis’s book is thorough and detailed. It quickly reminds the reader of the growing dispute between the United States and Mexico and then traces Taylor’s campaign from the formation of his Army of Observation through the key battles of Palo Alto, Resaca, Monterrey, and Buena Vista. -

T. Harry Williams Center for Oral History Collection ABSTRACT INTERVIEWEE NAME: Horace Wilkinson IV COLLECTION: 4700.1266 IDEN

T. Harry Williams Center for Oral History Collection ABSTRACT INTERVIEWEE NAME: Horace Wilkinson IV COLLECTION: 4700.1266 IDENTIFICATION: LSU student body president in 1962 INTERVIEWER: Jennifer Abraham SERIES: University History – Student Government Association Past Presidents INTERVIEW DATES: February 22, 2000 FOCUS DATES: 1950s-1960s ABSTRACT: Tape 1853, Side A Introduction; narrator is fourth man of same name in his lineage to attend LSU; family story about great grandfather writing check for LSU’s current campus; his predecessors all served in legislature and on LSU Board of Supervisors; attended University High School; born in West Baton Rouge, where family has lived for six generations; attended Port Allen Elementary; mother remarried after father died; father died of stroke at forty-eight while giving a speech at Capitol House; narrator was in hospital for infected lung when father died; transportation to and from University High; downtown Baton Rouge’s Paramount Theater; rise of shopping centers in 1950s decreased number of businesses in downtown Baton Rouge; businesses that used to be downtown; old African American preacher who lived in cardboard house; dispersal of siblings; plantations family owned; descended from General James Wilkinson; family goes way back in Louisiana politics; cousin has traced family back to Charlemagne, sixteen co-signers of the Magna Carta, and George Washington’s sister; also descended from Biddles of Philadelphia; grew up on sugar plantation, which was like feudal system; some of the quarters the