Winfield Scott (1786-1866) During the War of 1812

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Wilkinson and John Brown Letters to James Morrison

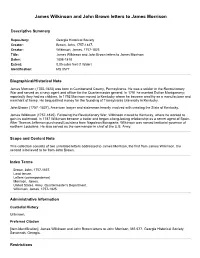

James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Brown, John, 1757-1837. Creator: Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Title: James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Dates: 1808-1818 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0577 Biographical/Historical Note James Morrison (1755-1823) was born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a soldier in the Revolutionary War and served as a navy agent and officer for the Quartermaster general. In 1791 he married Esther Montgomery; reportedly they had no children. In 1792 Morrison moved to Kentucky where he became wealthy as a manufacturer and merchant of hemp. He bequeathed money for the founding of Transylvania University in Kentucky. John Brown (1757 -1837), American lawyer and statesman heavily involved with creating the State of Kentucky. James Wilkinson (1757-1825). Following the Revolutionary War, Wilkinson moved to Kentucky, where he worked to gain its statehood. In 1787 Wilkinson became a traitor and began a long-lasting relationship as a secret agent of Spain. After Thomas Jefferson purchased Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte, Wilkinson was named territorial governor of northern Louisiana. He also served as the commander in chief of the U.S. Army. Scope and Content Note This collection consists of two unrelated letters addressed to James Morrison, the first from James Wilkinson, the second is believed to be from John Brown. Index Terms Brown, John, 1757-1837. Land tenure. Letters (correspondence) Morrison, James. United States. Army. Quartermaster's Department. Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Administrative Information Custodial History Unknown. Preferred Citation [item identification], James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to John Morrison, MS 577, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia. -

SHERMAN (WILLIAM T.) LETTERS (Mss

SHERMAN (WILLIAM T.) LETTERS (Mss. 1688) Inventory Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Reformatted 2003 Revised 2011 SHERMAN (WILLIAM T.) LETTERS Mss. 1688 1863-1905 LSU Libraries Special Collections CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 4 CROSS REFERENCES .................................................................................................................. 5 CONTAINER LIST ........................................................................................................................ 6 Use of manuscript materials. If you wish to examine items in the manuscript group, please fill out a call slip specifying the materials you wish to see. Consult the Container List for location information needed on the call slip. Photocopying. If you wish to request photocopies, please consult a staff member. The existing order and arrangement of unbound materials must be maintained. Publication. Readers assume full responsibility for compliance with laws regarding copyright, literary property rights, and libel. Permission to examine archival -

Senators You Have to Know John C. Calhoun –

Senators You Have To Know John C. Calhoun – South Carolina / serving terms in the United States House of Representatives, United States Senate and as the seventh Vice President of the United States (1825–1832), as well as secretary of war and state. Democrats After 1830, his views evolved and he became a greater proponent of states' rights, limited government, nullification and free trade; as he saw these means as the only way to preserve the Union. He is best known for his intense and original defense of slavery as something positive, his distrust of majoritarianism, and for pointing the South toward secession from the Union. Nullification is a legal theory that a state has the right to nullify, or invalidate, any federal law which that state has deemed unconstitutional. The theory of nullification has never been legally upheld;[1] rather, the Supreme Court has rejected it. The theory of nullification is based on a view that the States formed the Union by an agreement (or "compact") among the States, and that as creators of the federal government, the States have the final authority to determine the limits of the power of that government. Under this, the compact theory, the States and not the federal courts are the ultimate interpreters of the extent of the federal government's power. The States therefore may reject, or nullify, federal laws that the States believe are beyond the federal government's constitutional powers. The related idea of interposition is a theory that a state has the right and the duty to "interpose" itself when the federal government enacts laws that the state believes to be unconstitutional. -

The Storycontinues

FLORIDA . The Story Continues CHAPTER 10, The Age of Jackson (1828–1840) PEOPLE Mid 1700s: The Miccosukee Creeks settle in Florida. e Lower Creek and Upper Creek Indians moved from Georgia and Alabama to Florida in the mid-1700s. e two groups lived in Florida, but had di erent languages. e Upper Creek Indians came to be known as the Seminoles. e Lower Creek Indians, who came to be known as the Miccosukee, settled in central Florida where they built log cabins and farmed on communal plantations. Together the Seminoles and Miccosukee fought against the United States in the Seminole Wars. EVENTS 1832: The Seminole Indians are forced to sign the Treaty of Payne’s Landing. e Indian Removal Act of 1830 stated that all Native Americans who lived east of the Missis- sippi River must move to a newly created Indian Territory, in what is now Oklahoma. Two years later, Florida’s Seminole Indians were forced to sign the Treaty of Payne’s Landing, in which they stated they would move west to the Indian Territory and give up all of their claims to land in Florida. PEOPLE 1837: Chief Coacoochee (circa 1809–1857) escapes from the United States prison at Fort Marion. Chief Coa- coochee, whose name means “wild cat,” was a Seminole leader Florida. .The Story Continues during the Second Seminole War. After being captured by American soldiers in 1837, Coacoochee and a few Seminole cellmates escaped. Coacoochee returned to lead his people in See Chapter 1 battle against the United States. As the Seminole War contin- ued, the Native Americans su ered hunger and starvation when they could not plant crops to feed their people. -

Ambition Graphic Organizer

Ambition Graphic Organizer Directions: Make a list of three examples in stories or movies of characters who were ambitious to serve the larger good and three who pursued their own self-interested ambition. Then complete the rest of the chart. Self-Sacrificing or Self-Serving Evidence Character Movie/Book/Story Ambition? (What did they do?) 1. Self-Sacrificing 2. Self-Sacrificing 3. Self-Sacrificing 1. Self-Serving 2. Self-Serving 3. Self-Serving HEROES & VILLAINS: THE QUEST FOR CIVIC VIRTUE AMBITION Aaron Burr and Ambition any historical figures, and characters in son, the commander of the U.S. Army and a se- Mfiction, have demonstrated great ambition cret double-agent in the pay of the king of Spain. and risen to become important leaders as in politics, The two met privately in Burr’s boardinghouse and the military, and civil society. Some people such as pored over maps of the West. They planned to in- Roman statesman, Cicero, George Washington, and vade and conquer Spanish territories. Martin Luther King, Jr., were interested in using The duplicitous Burr also met secretly with British their position of authority to serve the republic, minister Anthony Merry to discuss a proposal to promote justice, and advance the common good separate the Louisiana Territory and western states with a strong moral vision. Others, such as Julius from the Union, and form an independent western Caesar, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Adolf Hitler were confederacy. Though he feared “the profligacy of often swept up in their ambitions to serve their own Mr. Burr’s character,” Merry was intrigued by the needs of seizing power and keeping it, personal proposal since the British sought the failure of the glory, and their own self-interest. -

![Baine's [!] History of the Late](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7311/baines-history-of-the-late-307311.webp)

Baine's [!] History of the Late

y'^^^^ > .3 ^.. v-^^ .o< ^ r^: c"^ 00 ,*^ v: 0" ^ * ^t. v^^ :^, A^ iv '=t ^^ 00^ oH vO V,-^ •^.-^77;^^G^ Oo. A -f. ?: -%.%^ °-'>^i^'.' ^>- 'If, . -vV 1 "'r-t/t/'*^ "i" v^ .''^ «^r "^ - /^ ^ *<, s^ ^0 ^ ^ s}> -r;^. ^^. .- .>r-^. ^ '^ '^. ,^^«iy' c « O. ..s^J^ i^ » ,,$^ 'V. aN^' -. ^ ^ s , o * O , ^ y 0" .. °^ :f' .1 / BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND GREAT BRITAIN; WITH A CTJllTlCAli ATTEXmX, &c BY EBENEZER HARLOW CUMMINS, A. M. BALTIMOBE: riinted by Benja. Edes, corner of Second and Ga/.streets 1820. ADVERTISEMENT. Since the late hostilities with Great Britain, several books have been published in the United States purporting to be histories of tiie war. No one of tliem, it is believed, can be received as generally authentic: the whole adding little to the literary char- acter of the country. Of those most g-en'^rally circulated, we can speak the least favourably, as specimens of history, which means something more than compilations from newspapers, or a tirade of epithets stigmatising our adversaries. Two or three stipendi- aries occupied the fore ground in the race of the booksellers for the market of the United States, producing interesting though coarse compilations; which, while the feelings created by the war were still in Hvely existence, were read with sensations of pleas- ure. But no one now will ascribe to their works, the name, much less the character of history. Weems' life of Marion, in which the author has collated and embellished many interesting events, with the view to a popular book, has greatly superiour pretensions to either. With enough of fact to challenge, at this late day, the credence of most readers, it excels in all kinds of jest and fancy; and administers abundantly of the finest entertain- ment to the lovers of fun. -

Missouri Compromise (1820) • Compromise Sponsored by Henry Clay

Congressional Compromises and the Road to War The Great Triumvirate Henry Clay Daniel Webster John C. Calhoun representing the representing representing West the North the South John C. Calhoun •From South Carolina •Called “Cast-Iron Man” for his stubbornness and determination. •Owned slaves •Believed states were sovereign and could nullify or reject federal laws they believed were unconstitutional. Daniel Webster •From Massachusetts •Called “The Great Orator” •Did not own slaves Henry Clay •From Kentucky •Called “The Great Compromiser” •Owned slaves •Calmed sectional conflict through balanced legislation and compromises. Missouri Compromise (1820) • Compromise sponsored by Henry Clay. It allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a Slave State and Maine to enter as a Free State. The southern border of Missouri would determine if a territory could allow slavery or not. • Slavery was allowed in some new states while other states allowed freedom for African Americans. • Balanced political power between slave states and free states. Nullification Crisis (1832-1833) • South Carolina, led by Senator John C. Calhoun declared a high federal tariff to be null and avoid within its borders. • John C. Calhoun and others believed in Nullification, the idea that state governments have the right to reject federal laws they see as Unconstitutional. • The state of South Carolina threatened to secede or break off from the United States if the federal government, under President Andrew Jackson, tried to enforce the tariff in South Carolina. Andrew Jackson on Nullification “The laws of the United States, its Constitution…are the supreme law of the land.” “Look, for a moment, to the consequence. -

Library Company of Philadelphia Mca 5792.F CIVIL WAR LEADERS

Library Company of Philadelphia McA 5792.F CIVIL WAR LEADERS EPHEMERA COLLECTION 1860‐1865 1.88 linear feet, 2 boxes Series I. Small Ephemera, 1860‐1865 Series II. Oversize Material, 1860s March 2006 McA MSS 004 2 Descriptive Summary Repository Library Company of Philadelphia 1314 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107‐5698 Call Number McA 5792.F Creator McAllister, John A. (John Allister), 1822‐1896. Title Civil War Leaders Ephemera Collection Inclusive Dates 1860‐1865 Quantity 1.88 linear feet (2 boxes) Language of Materials Materials are in English. Abstract The Civil War Leaders Ephemera Collection holds ephemera and visual materials related to a group of prominent American politicians and military heroes active in the middle of the nineteenth century: Robert Anderson, William G. Brownlow, Jefferson Davis, Abraham Lincoln, George B. McClellan, and Winfield Scott. Administrative Information Restrictions to Access The collection is open to researchers. Acquisition Information Gift of John A. McAllister; forms part of the McAllister Collection. Processing Information The Civil War Leaders Ephemera Collection was formerly housed in four folio albums that had been created after the McAllister Collection arrived at the Library Company. The material was removed from the albums, arranged, and described in 2006, under grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the William Penn Foundation. The collection was processed by Sandra Markham. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this finding aid do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Preferred Citation This collection should be cited as: [indicate specific item or series here], Civil War Leaders Ephemera Collection (McA 5792.F), McAllister Collection, The Library Company of Philadelphia. -

Washington and Saratoga Counties in the War of 1812 on Its Northern

D. Reid Ross 5-8-15 WASHINGTON AND SARATOGA COUNTIES IN THE WAR OF 1812 ON ITS NORTHERN FRONTIER AND THE EIGHT REIDS AND ROSSES WHO FOUGHT IT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Illustrations Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown 3 Map upstate New York locations 4 Map of Champlain Valley locations 4 Chapters 1. Initial Support 5 2. The Niagara Campaign 6 3. Action on Lake Champlain at Whitehall and Training Camps for the Green Troops 10 4. The Battle of Plattsburg 12 5. Significance of the Battle 15 6. The Fort Erie Sortie and a Summary of the Records of the Four Rosses and Four Reids 15 7. Bibliography 15 2 Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown as depicted3 in an engraving published in 1862 4 1 INITIAL SUPPORT Daniel T. Tompkins, New York’s governor since 1807, and Peter B. Porter, the U.S. Congressman, first elected in 1808 to represent western New York, were leading advocates of a war of conquest against the British over Canada. Tompkins was particularly interested in recruiting and training a state militia and opening and equipping state arsenals in preparation for such a war. Normally, militiamen were obligated only for three months of duty during the War of 1812, although if the President requested, the period could be extended to a maximum of six months. When the militia was called into service by the governor or his officers, it was paid by the state. When called by the President or an officer of the U.S. Army, it was paid by the U.S. Treasury. In 1808, the United States Congress took the first steps toward federalizing state militias by appropriating $200,000 – a hopelessly inadequate sum – to arm and train citizen soldiers needed to supplement the nation’s tiny standing army. -

Rather Dead Than Enslaved: the Blacks of York in the War of 1812 by Peter Meyler

The Newsletter of The Friends of Fort York and Garrison Common v. 16 No.4 Sept 2012 1 Rather Dead than Enslaved: The Blacks of 5 The Soldiers at Fort York Armoury York in the War of 1812 7 Bicentennial Timeline 2 “Particularly Torontoesque”: 8 Administrator’s Report Commemorating the Centennial of 9 Tracking Nature at Fort York the War of 1812 11 Upcoming Events 4 Brock Day in Guernsey Rather Dead than Enslaved: The Blacks of York in the War of 1812 by Peter Meyler In 1812 York may have been a “dirty straggling village,” but Upper Canada’s capital was also a place of diversity. Government officials, soldiers, merchants, and artisans mixed with clerks, servants, and even slaves in a town of barely 700 persons. The number who were Black can only be guessed at. Some were freeborn, others had escaped slavery from the United States, but a number were slaves. Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe’s 1793 Act prevented the further importation of slaves into Upper Canada, but did not free those who were enslaved. Among the province’s slave-owners was Robert Gray, the solicitor general. His household at York included his manservant, Simon Baker, Simon’s brother John, and two Black female servants. In 1804 Gray and Simon both perished when the Speedy, a ship on which they were travelling, was lost in a storm on Lake Ontario. Under Gray’s will, all his slaves were freed. During the War of 1812 John Baker left York and served with the 104th New Brunswick Regiment. He later returned to Upper Canada to live in Cornwall where he died in his nineties. -

Book Reviews from Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: a Journal of The

Book Reviews 425 From Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: A Journal of the Wayne Campaign, July 28-September 14, 1794, Edited by Dwight L. Smith. Volume XVI, Number 3, Indiana Historical Society PublicaCions. (Indianapolis : Indiana Historical Society, 1952, pp. 95. Index. $1.00.) With the publication of this journal dealing with the Wayne campaign the historian is furnished with additional documentary evidence concerning the intrigue of one of the most ambitious and treasonable figures in American history, General James Wilkinson. Despite the fact that the writer of this journal remains anonymous, his outspoken support of the wily Wilkinson is significant in that it substantiates in an intimate fashion the machinations of Wilkinson against his immediate military superior, General Anthony Wayne. The reader cannot help but be impressed with this evidence of the great influence of Wilkinson’s personal magnetism, which simultaneously won for him a pension from the Span- ish monarch and the support of many Americans a few years prior to the launching of this campaign. The journal covers the crucial days from July 28 to September 14, 1794, during which time Wayne and his men advanced from Fort Greene Ville to a place in the Maumee Valley known as Fallen Timbers, where the Indian Confed- eration was dealt a body blow. Included in it are many de- tails such as supply problems, geographical features, and personalities. Unfortunately, the pronounced pro-Wilkinson bias of the writer inclines the reader to exercise mental reservations in accepting much of the information even though it be of a purely factual nature. In a brief but able introduction, Smith sets the stage for this account of this military expedition of General Wayne against the Indians of the Old Northwest. -

Civil War 150 Reader 4

CIVIL WAR 150 • READER #4 Contents From SLAVERY to FREEDOM Introduction by Thavolia Glymph . 3 Introduction by Thavolia Glymph Benjamin F. Butler to Winfield Scott, May 24 , 1861 . 6 Abraham Lincoln to Orville H. Browning, September 22 , 1861 . 9 Let My People Go, December 21 , 1861 . 12 Frederick Douglass: What Shall be Done with the Slaves If Emancipated? January 1862 . 16 John Boston to Elizabeth Boston, January 12 , 1862 . 21 George E. Stephens to the Weekly Anglo-African, March 2, 1862 . 23 Garland H. White to Edwin M. Stanton, May 7, 1862 . 28 Memorial of a Committee of Citizens of Liberty County, Georgia, August 5, 1862 . 30 Harriet Jacobs to William Lloyd Garrison, September 5, 1862 . 36 Abraham Lincoln: Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, CIVIL WAR 372: Exploring the War and Its September 22 , 1862 . 45 Meaning Through the Words of Those Who Lived It Debate in the Confederate Senate on Retaliation for is a national public programing initiative designed to encourage the Emancipation Proclamation, September 29 , October 1, 1862 . 49 public exploration of the transformative impact and contested meanings of the Civil War through primary documents and firsthand accounts. Samuel Sawyer, Pearl P. Ingalls, and Jacob G. Forman to Samuel R. Curtis, December 29 , 1862 . 54 Abraham Lincoln: Final Emancipation Proclamation, The project is presented by January 1, 1863 . 56 The Library of America Biographical Notes . 59 Chronology . 64 in partnership with Questions for Discussion . 67 and is supported by a grant from Introduction Introduction, headnotes, and back matter copyright © 2012 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.