Wilkinson's Invasion Flotilla of 1813: a Paper Examining the American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Wilkinson and John Brown Letters to James Morrison

James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Brown, John, 1757-1837. Creator: Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Title: James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to James Morrison Dates: 1808-1818 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0577 Biographical/Historical Note James Morrison (1755-1823) was born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. He was a soldier in the Revolutionary War and served as a navy agent and officer for the Quartermaster general. In 1791 he married Esther Montgomery; reportedly they had no children. In 1792 Morrison moved to Kentucky where he became wealthy as a manufacturer and merchant of hemp. He bequeathed money for the founding of Transylvania University in Kentucky. John Brown (1757 -1837), American lawyer and statesman heavily involved with creating the State of Kentucky. James Wilkinson (1757-1825). Following the Revolutionary War, Wilkinson moved to Kentucky, where he worked to gain its statehood. In 1787 Wilkinson became a traitor and began a long-lasting relationship as a secret agent of Spain. After Thomas Jefferson purchased Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte, Wilkinson was named territorial governor of northern Louisiana. He also served as the commander in chief of the U.S. Army. Scope and Content Note This collection consists of two unrelated letters addressed to James Morrison, the first from James Wilkinson, the second is believed to be from John Brown. Index Terms Brown, John, 1757-1837. Land tenure. Letters (correspondence) Morrison, James. United States. Army. Quartermaster's Department. Wilkinson, James, 1757-1825. Administrative Information Custodial History Unknown. Preferred Citation [item identification], James Wilkinson and John Brown letters to John Morrison, MS 577, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia. -

The Documentary History of the Campaign on the Niagara Frontier in 1814

Documentary History 9W ttl# ampatgn on tl?e lagara f rontier iMiaM. K«it*«l fisp the Luntfy« Lfluiil "'«'>.,-,.* -'-^*f-:, : THE DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF THE CAMPAIGN ON THE - NIAGARA FRONTIER IN 1814. EDITED FOR THE LUNDTS LANE HISTORICAL SOCIETY BY CAPT. K. CRUIK8HANK. WELLAND PRINTBD AT THE THIBVNK OKKICB. F-5^0 15 21(f615 ' J7 V.I ^L //s : The Documentary History of the Campaign on the Niagara Frontier in 1814. LIEVT.COL. JOHN HARVEY TO Mkl^-iiE^, RIALL. (Most Beoret and Confidential.) Deputy Adjutant General's Office, Kingston, 28rd March, 1814. Sir,—Lieut. -General Drummond having had under his con- sideration your letter of the 10th of March, desirinjr to be informed of his general plan of defence as far as may be necessary for your guidance in directing the operations of the right division against the attempt which there is reason to expect will be made by the enemy on the Niagara frontier so soon as the season for operations commences, I have received the commands of the Lieut.-General to the following observations instructions to communicate you and y The Lieut. -General concurs with you as to the probability of the enemy's acting on the ofTensive as soon as the season permits. Having, unfortunately, no accurate information as to his plans of attack, general defensive arrangements can alone be suggested. It is highly probable that independent of the siege of Fort Niagara, or rather in combination with the atttick on that place, the enemy \vill invade the District of Niagara by the western road, and that he may at the same time land a force at Long Point and per- haps at Point Abino or Fort Erie. -

North Country Notes

Clinton County Historical Association North Country Notes Issue #414 Fall, 2014 Henry Atkinson: When the Lion Crouched and the Eagle Soared by Clyde Rabideau, Sn I, like most people in this area, had not heard of ing the same year, they earned their third campaigu Henry Atkinson's role in the history of Plattsburgh. streamer at the Battle of Lundy Lane near Niagara It turns out that he was very well known for serving Falls, when they inflicted heavy casualties against the his country in the Plattsburgh area. British. Atkinson was serving as Adjutant-General under Ma- jor General Wade Hampton during the Battle of Cha- teauguay on October 25,1814. The battle was lost to the British and Wade ignored orders from General James Wilkinson to return to Cornwall. lnstead, he f retreated to Plattsburgh and resigned from the Army. a Colonel Henry Atkinson served as commander of the a thirty-seventh Regiment in Plattsburgh until March 1, :$,'; *'.t. 1815, when a downsizing of the Army took place in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The 6'h, 11'h, 25'h, Brigadier General Henry Atkinson 2'7th, zgth, and 37th regiments were consolidated into Im age courtesy of www.town-of-wheatland.com the 6th Regiment and Colonel Henry Atkinson was given command. The regiment was given the number While on a research trip, I was visiting Fort Atkin- sixbecause Colonel Atkinson was the sixth ranking son in Council Bluffs, Nebraska and picked up a Colonel in the Army at the time. pamphlet that was given to visitors. -

Ambition Graphic Organizer

Ambition Graphic Organizer Directions: Make a list of three examples in stories or movies of characters who were ambitious to serve the larger good and three who pursued their own self-interested ambition. Then complete the rest of the chart. Self-Sacrificing or Self-Serving Evidence Character Movie/Book/Story Ambition? (What did they do?) 1. Self-Sacrificing 2. Self-Sacrificing 3. Self-Sacrificing 1. Self-Serving 2. Self-Serving 3. Self-Serving HEROES & VILLAINS: THE QUEST FOR CIVIC VIRTUE AMBITION Aaron Burr and Ambition any historical figures, and characters in son, the commander of the U.S. Army and a se- Mfiction, have demonstrated great ambition cret double-agent in the pay of the king of Spain. and risen to become important leaders as in politics, The two met privately in Burr’s boardinghouse and the military, and civil society. Some people such as pored over maps of the West. They planned to in- Roman statesman, Cicero, George Washington, and vade and conquer Spanish territories. Martin Luther King, Jr., were interested in using The duplicitous Burr also met secretly with British their position of authority to serve the republic, minister Anthony Merry to discuss a proposal to promote justice, and advance the common good separate the Louisiana Territory and western states with a strong moral vision. Others, such as Julius from the Union, and form an independent western Caesar, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Adolf Hitler were confederacy. Though he feared “the profligacy of often swept up in their ambitions to serve their own Mr. Burr’s character,” Merry was intrigued by the needs of seizing power and keeping it, personal proposal since the British sought the failure of the glory, and their own self-interest. -

Perth's Built Heritage

PERTH’S BUILT HERITAGE Anderson-Foss Law Building (1856) – 10 Market Square Asbury Free Methodist Church (1884) – 144 Gore Street East Bain House (1847) – 4 South Street Band Stand (1931) – Market Square Bank of Montreal (1884) - 30 Gore Street East Bridgemaster’s House (1889) – Beckwith Street & Riverside Drive Carnegie Library / McMillan Building (1907) – 77 Gore Street East Code’s Mill (1842-1902) & Kininvie House (1907) – 50/53 Herriott Street Courthouse (1843) - 41 Drummond Street East Craig Street Cemetery / Old Burying Ground (1818) – 21 Brock Street South Daly-Reid Building (1880) - 13 Gore Street West Doctor’s House (1840s) – 22 Wilson Street West Firehall (1855 & 1883) – 34 Herriott Street Grant Building (1860s) – 89-91 Gore Street East Haggart House (1837), Haggart Mill and Dam (1840) - 41 Mill Street Inge-Va (1824) - 66 Craig Street Hart / O’Donnell House (1842) – 37 Herriott Street Hope Building (1886) – 69-71 Foster Street Jail / Gaol (1863) – 62 Beckwith Street Kellock Block (1848) - 39-43 Gore Street East Lillie House (1863) – 43-45 North Street Maple Drop Building / Butler Building (1884) – 2-6 Wilson Street East Matheson House (1840) – 11 Gore Street East Matthews Building (1846) – 55 Gore Street East McKay House (c1820) - 9 Mill Street McLaren Building (1874) – 85-87 Gore Street East McMartin House (1830) – 125 Gore Street East Methodist Robinson Street Cemetery (1841) – 1 Robinson Street Nevis Estate (1842) – 61 Drummond Street West Perkins Building (1947) – 2 Wilson Street West Red House (1816) - 55 Craig Street Registry -

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Valcour_Island Coordinates: 44°36′37.84″N 73°25′49.39″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The naval Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, took place on October 11, 1776, on Battle of Valcour Island Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Part of the American Revolutionary War Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island. The battle is generally regarded as one of the first naval battles of the American Revolutionary War, and one of the first fought by the United States Navy. Most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold were captured or destroyed by a British force under the overall direction of General Guy Carleton. However, the American defense of Lake Champlain stalled British plans to reach the upper Hudson River valley. The Continental Army had retreated from Quebec to Fort Royal Savage is shown run aground and burning, Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point in June 1776 after while British ships fire on her (watercolor by British forces were massively reinforced. They spent the unknown artist, ca. 1925) summer of 1776 fortifying those forts, and building additional ships to augment the small American fleet Date October 11, 1776 already on the lake. General Carleton had a 9,000 man Location near Valcour Bay, Lake Champlain, army at Fort Saint-Jean, but needed to build a fleet to carry Town of Peru / Town of Plattsburgh, it on the lake. -

Book Reviews from Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: a Journal of The

Book Reviews 425 From Greene Ville to Fallen Timbers: A Journal of the Wayne Campaign, July 28-September 14, 1794, Edited by Dwight L. Smith. Volume XVI, Number 3, Indiana Historical Society PublicaCions. (Indianapolis : Indiana Historical Society, 1952, pp. 95. Index. $1.00.) With the publication of this journal dealing with the Wayne campaign the historian is furnished with additional documentary evidence concerning the intrigue of one of the most ambitious and treasonable figures in American history, General James Wilkinson. Despite the fact that the writer of this journal remains anonymous, his outspoken support of the wily Wilkinson is significant in that it substantiates in an intimate fashion the machinations of Wilkinson against his immediate military superior, General Anthony Wayne. The reader cannot help but be impressed with this evidence of the great influence of Wilkinson’s personal magnetism, which simultaneously won for him a pension from the Span- ish monarch and the support of many Americans a few years prior to the launching of this campaign. The journal covers the crucial days from July 28 to September 14, 1794, during which time Wayne and his men advanced from Fort Greene Ville to a place in the Maumee Valley known as Fallen Timbers, where the Indian Confed- eration was dealt a body blow. Included in it are many de- tails such as supply problems, geographical features, and personalities. Unfortunately, the pronounced pro-Wilkinson bias of the writer inclines the reader to exercise mental reservations in accepting much of the information even though it be of a purely factual nature. In a brief but able introduction, Smith sets the stage for this account of this military expedition of General Wayne against the Indians of the Old Northwest. -

030321 VLP Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga readies for new season LEE MANCHESTER, Lake Placid News TICONDEROGA — As countered a band of Mohawk Iro- name brought the eastern foothills American forces prepared this quois warriors, setting off the first of the Adirondack Mountains into week for a new war against Iraq, battle associated with the Euro- the territory worked by the voya- historians and educators in Ti- pean exploration and settlement geurs, the backwoods fur traders conderoga prepared for yet an- of the North Country. whose pelts enriched New other visitors’ season at the site of Champlain’s journey down France. Ticonderoga was the America’s first Revolutionary the lake which came to bear his southernmost outpost of the War victory: Fort Ticonderoga. A little over an hour’s drive from Lake Placid, Ticonderoga is situated — town, village and fort — in the far southeastern corner of Essex County, just a short stone’s throw across Lake Cham- plain from the Green Mountains of Vermont. Fort Ticonderoga is an abso- lute North Country “must see” — but to appreciate this historical gem, one must know its history. Two centuries of battle It was the two-mile “carry” up the La Chute River from Lake Champlain through Ticonderoga village to Lake George that gave the site its name, a Mohican word that means “land between the wa- ters.” Overlooking the water highway connecting the two lakes as well as the St. Lawrence and Hudson rivers, Ticonderoga’s strategic importance made it the frontier for centuries between competing cultures: first between the northern Abenaki and south- ern Mohawk natives, then be- tween French and English colo- nizers, and finally between royal- ists and patriots in the American Revolution. -

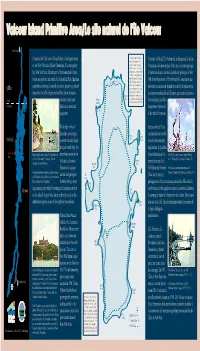

Valcour Primitive Area

Chambly Canal L’île Valcour comporte 12 km de Comprised of 1,100 acres, Valcour Island is the largest island sentiers de randonnée et 25 Couvrant 4,45 km2, l’île Valcour est la plus grande île du lac emplacements de camping on the New York side of Lake Champlain. It is managed by désignés. Des permis de camping Champlain, côté new-yorkais. Cette zone de nature protégée gratuits d’une durée maximale de the New York State Department of Environmental Conser- 14 jours sont émis par un gardien à l’intérieur du parc des Adirondacks est gérée par le New du parc. Par ailleurs, le site ayant vation as a primitive area within the Adirondack Park. Emphasis adopté le principe du premier York State Department of Environmental Conservation qui is placed on restoring its natural condition, preserving cultural arrivé, premier servi, aucune réser- préconise la restauration du milieu naturel et la préservation Quebec vation n’est acceptée. Pour de plus resources, and affording recreation that does not require amples renseignements sur l’île des ressources culturelles de l’île ainsi que les activités récréa- Beauty Valcour, veuillez communiquer Bay avec le Department of Environmen- Canada extensive man-made Valcour tives n’exigeant pas d’am- Landing tal Conservation au (518) 897-1200. United States facilities or motorized énagements importants equipment. ni de matériel motorisé. With eight miles of Avec sa côte de 13 km shoreline, consisting of constituée d’une variété Spoon Spoon New York a variety of rocky ledges Bay Island de corniches rocheuses and quiet sandy bays, the surplombant de paisibles You Are Here Boating along the rocky ledges of Valcour Island at the recreational potential on baies sablonneuses, le “Baby Blues,” similar to scenes found on Valcour Peru turn of the 19th century. -

King of Battle

tI'1{1l1JOC 'Branch !J{istory Series KING OF BATTLE A BRANCH HISTORY OF THE U.S. ARMY'S FIELD ARTILLERY By Boyd L. Dastrup Office of the Command 9iistorian runited States !Jl.rmy rrraining and tIJoctrine Command ASS!STANT COMMANDANT US/\F/\S 11 MAR. 1992 ATTIN' II,., ..." (' '. 1\iIO.tIS ,")\,'/2tt Tech!lical librar fort SII), OK ~3503'031~ ..~ TRADOC Branch History Series KING OF BATTLE A BRANCH HISTORY OF THE U.S. ARMY'S FIELD ARTILLERY I t+ j f I by f f Boyd L. Dastrup Morris Swett T. n1 Property of' '1 seCh cal Library, USAFAS U.l• .1:ruy Office of the Command Historian United States Army Training and Doctrine Command Fort Monroe, Virginia 1992 u.s. ARMY TRAINING AND DOCTRINE COMMAND General Frederick M. Franks, Jr.. Commander M~or General Donald M. Lionetti Chief of Staff Dr. Henry O. Malone, Jr. Chief Historian Mr. John L. Romjue Chief, Historical Studies and Publication TRADOC BRANCH HISTORY SERIES Henry O. Malone and John L. Romjue, General Editors TRADOC Branch Histories are historical studies that treat the Army branches for which TRADOC has Armywide proponent responsibility. They are intended to promote professional development of Army leaders and serve a wider audience as a reference source for information on the various branches. The series presents documented, con- cise narratives on the evolution of doctrine, organization, materiel, and training in the individual Army branches to support the Command's mission of preparing the army for war and charting its future. iii Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dastrup, Boyd L. -

Niagara National Historic Sites of Canada Draft Management Plan 2018

Management Plan Niagara 2018 National Historic Sites of Canada 2018 DRAFT Niagara National Historic Sites of Canada Draft Management Plan ii Niagara National Historic Sites iii Draft Management Plan Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................... 1 2.0 Significance of Niagara National Historic Sites .............................. 1 3.0 Planning Context ............................................................................ 3 4.0 Vision .............................................................................................. 5 5.0 Key Strategies ................................................................................ 5 6.0 Management Areas ......................................................................... 9 7.0 Summary of Strategic Environmental Assessment ....................... 12 Maps Map 1: Regional Setting ....................................................................... 2 Map 2: Niagara National Historic Sites Administered by Parks Canada in Niagara-on-the-Lake ........................................................... 4 Map 3: Lakeshore Properties and Battlefield of Fort George National Historic Site .......................................................................... 10 iv Niagara National Historic Sites 1 Draft Management Plan 1.0 Introduction Parks Canada manages one of the finest and most extensive systems of protected natural and historic places in the world. The Agency’s mandate is to protect and present these places -

Northwest Ohio Quarterly Volume 16 Issue 2

Northwest Ohio Quarterly Volume 16 Issue 2 Toledo and Fort Miami UR general interest in the site of Fort Miami, located on the west bank of the Maumee River in Lucas County. wi thin the O corporate limits of the Village of Maumee, goes hack at least two generations. In the 1880's a movement was commenced by citizens of j\·faumcc Valley wh ich foreshadowed the activities of the present vigorous Maumee Scenic and H istoric Highway Association. At that time it was thought that solution lay in federal d evelopment of this and the other historic sites of northwestern Ohio. Surveys of these sites were made by U. S, Army engineers, pursuant to legis lation sponsored by Jacob Romcis of 'Toledo. The survey o f Fort "Miami in 1888 is reproduced in th is issue. Nothing came of this movement, however, and little was apparently done to reclaim lhe site from the pastoral scenes pictured in the illustrated section of this issue until the first World War. T h is movement subsided u nder the inflated realty prices of the times. The acti"e story, the begin· ning of the movement which finally saved the site for posterity, commences with the organization of the Maumee River Scenic and Historic Highway Association in 1939. The details of this fi ght are given in the October, 1942, issue of our Q UARTERLY, and can only be summarized here. The fo llowing names appear in the forefront: T he organizers of the Maumee River group, l\ofr. Ralph Peters, of the Defian ce Crescent·News, Mr.