Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Country Notes

Clinton County Historical Association North Country Notes Issue #414 Fall, 2014 Henry Atkinson: When the Lion Crouched and the Eagle Soared by Clyde Rabideau, Sn I, like most people in this area, had not heard of ing the same year, they earned their third campaigu Henry Atkinson's role in the history of Plattsburgh. streamer at the Battle of Lundy Lane near Niagara It turns out that he was very well known for serving Falls, when they inflicted heavy casualties against the his country in the Plattsburgh area. British. Atkinson was serving as Adjutant-General under Ma- jor General Wade Hampton during the Battle of Cha- teauguay on October 25,1814. The battle was lost to the British and Wade ignored orders from General James Wilkinson to return to Cornwall. lnstead, he f retreated to Plattsburgh and resigned from the Army. a Colonel Henry Atkinson served as commander of the a thirty-seventh Regiment in Plattsburgh until March 1, :$,'; *'.t. 1815, when a downsizing of the Army took place in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The 6'h, 11'h, 25'h, Brigadier General Henry Atkinson 2'7th, zgth, and 37th regiments were consolidated into Im age courtesy of www.town-of-wheatland.com the 6th Regiment and Colonel Henry Atkinson was given command. The regiment was given the number While on a research trip, I was visiting Fort Atkin- sixbecause Colonel Atkinson was the sixth ranking son in Council Bluffs, Nebraska and picked up a Colonel in the Army at the time. pamphlet that was given to visitors. -

Wayneflete Tower, Esher, Surrey

Wessex Archaeology Wayneflete Tower, Esher, Surrey. Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 59472.01 March 2006 Wayneflete Tower, Esher, Surrey Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON SW1 8QP By Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 59472.01 March 2006 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2006, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................5 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................5 1.2 Description of the Site................................................................................5 1.3 Historical Background...............................................................................5 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work ...............................................................12 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES...............................................................................13 3 METHODS.........................................................................................................14 3.1 Introduction..............................................................................................14 3.2 Dendrochronological Survey...................................................................14 3.3 Geophysical Survey..................................................................................14 -

A Possible Ring Fort from the Late Viking Period in Helsingborg

A POSSIBLE RING FORT FROM THE LATE VIKING PERIOD IN HELSINGBORG Margareta This paper is based on the author's earlier archaeologi- cal excavations at St Clemens Church in Helsingborg en-Hallerdt Weidhag as well as an investigation in rg87 immediately to the north of the church. On this occasion part of a ditch from a supposed medieval ring fort, estimated to be about a7o m in diameter, was unexpectedly found. This discovery once again raised the question as to whether an early ring fort had existed here, as suggested by the place name. The probability of such is strengthened by the newly discovered ring forts in south-western Scania: Borgeby and Trelleborg. In terms of time these have been ranked with four circular fortresses in Denmark found much earlier, the dendrochronological dating of which is y8o/g8r. The discoveries of the Scanian ring forts have thrown new light on south Scandinavian history during the period AD yLgo —zogo. This paper can thus be regarded as a contribution to the debate. Key words: Viking Age, Trelleborg-type fortress, ri»g forts, Helsingborg, Scania, Denmark INTRODUCTION Helsingborg's location on the strait of Öresund (the Sound) and its special topography have undoubtedly been of decisive importance for the establishment of the town and its further development. Opinions as to the meaning of the place name have long been divided, but now the military aspect of the last element of the name has gained the up- per. hand. Nothing in the find material indicates that the town owed its growth to crafts, market or trade activity. -

Mesa Verde National Park

MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK • COLORADO • UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR M A TIONAL PARR SERV ICE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HAROLD L. I CKES, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AR.NO I!. CAMMLRKR, Director MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK COLORADO SEASON FROM MAY 15 TO OCTOBER 15 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1934 RULES AND REGULATIONS Automobiles.—Drive carefully; free-wheeling is prohibited within the park. Obey park traffic rules and speed limits. Secure automobile permit, fee Si .00 per car. Fires.—Confine fires to designated places. Extinguish completely before leaving camp, even for temporary absences. Do not guess your fire is out— KNOW IT. Firewood.—Use only the wood that is stacked and marked "firewood" near your campsite. By all means do not use your axe on any standing tree or strip bark from the junipers. Grounds.—Burn all combustible rubbish before leaving your camp. Do not throw papers, cans, or other refuse on the ground or over the canyon rim. Use the incinerators which are placed for this purpose. Hiking.—Do not venture away from the headquarters area unless accompanied by a guide or after first having secured permission from a duly authorized park officer. Hunting.—Hunting is prohibited within the park. This area is a sanctuary for all wild life. Noises.—Be epiiet in camp after others have gone to bed. Many people come here for rest. Park rangers.—The rangers are here to help and advise you as well as to enforce regulations. When in doubt ask a ranger. Ruins and structures.—Do not mark, disturb, or injure in any way the ruins or any of the buildings, signs, or other properties within the park. -

On the Trail

EXPERIENCE HISTORY Discover the secrets of the Royal City ON THE TRAIL Every LITTLE CORNER charmingly Franconian. ON THE TRAIL OF KINGS. Forchheim, one of the oldest cities in Franconia, has preserved its medieval appearance with its many half-timbered houses and fortress. Archaeological excavations show that the Regnitz Valley, which surrounds Forchheim, was inhabited as long ago as prehistoric times. In the 7th century, the Franks established a small sett- lement here. Thanks to its transport-favourable location, it soon developed into an important centre of long-distance trade that even served as a royal court, particularly for the late Carolingian kings. « Embark on a voyage of discovery and enjoy a vivid experience of the history of Forchheim, a city steeped in tradition. SET OFF ON THE TRAIL: With our city map, you can discover the historical centre of Forchheim on your own. Take a stroll, or simply follow the attractions along the cobblestone lanes of splendid half-timbered houses. All the attractions can easily be reached on foot. EXPERIENCE MORE IN FORCHHEIM. Would you like to see another side of our city? Our tour guides will be happy to take you along! In addition to a guided, 90-minute tour, you can enjoy exciting theme tours such as a visit to the Forchheim fortifications, a Segway excursion or a look inside the local breweries. Of course, there is an exciting discovery tour for our little guests as well. You will find all the information about our guided tours at the Tourist Information Centre in the Kaiserpfalz Kapellenstraße 16 | 91301 Forchheim or online at www.forchheim-erleben.de All information supplied without guarantee. -

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Valcour_Island Coordinates: 44°36′37.84″N 73°25′49.39″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The naval Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, took place on October 11, 1776, on Battle of Valcour Island Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Part of the American Revolutionary War Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island. The battle is generally regarded as one of the first naval battles of the American Revolutionary War, and one of the first fought by the United States Navy. Most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold were captured or destroyed by a British force under the overall direction of General Guy Carleton. However, the American defense of Lake Champlain stalled British plans to reach the upper Hudson River valley. The Continental Army had retreated from Quebec to Fort Royal Savage is shown run aground and burning, Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point in June 1776 after while British ships fire on her (watercolor by British forces were massively reinforced. They spent the unknown artist, ca. 1925) summer of 1776 fortifying those forts, and building additional ships to augment the small American fleet Date October 11, 1776 already on the lake. General Carleton had a 9,000 man Location near Valcour Bay, Lake Champlain, army at Fort Saint-Jean, but needed to build a fleet to carry Town of Peru / Town of Plattsburgh, it on the lake. -

An Ancient Cave Sanctuary Underneath the Theatre of Miletus

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Philipp Niewöhner An Ancient Cave Sanctuary underneath the Theatre of Miletus, Beauty, Mutilation, and Burial of Ancient Sculpture in Late Antiquity, and the History of the Seaward Defences aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue 1 • 2016 Seite / Page 67–156 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa/1931/5962 • urn:nbn:de:0048-journals.aa-2016-1-p67-156-v5962.3 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentrale | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 Verlag / Publisher Ernst Wasmuth Verlag GmbH & Co. Tübingen ©2017 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). -

From Privateer, to Schooner Captain, to Raider

From Privateer, to Schooner Captain, to Raider The destruction of commercial shipping during the war hurt local merchants. Capt. David Hawley decided to recoup his losses by turning privateer. In March 1776 he sailed out of Stratford, but was captured by the British. He was sent to Halifax where he and 8 men were able to steal a small boat and escape. By May 18, he was in Hartford. In August 1776, the Connecticut General Court ordered Capt. Hawley to Lake Champlain with a small naval detachment to serve under Benedict Arnold in the northern campaign. He commanded the schooner, Royal Savage, built on the lake, armed with four 6- The Battle of Valcour Island pounders and eight 4- pounders cannons. In the battle of Oct. 12, Royal Savage was out-gunned by the British ship Carleton and driven ashore on Valcour Island. While the British won the battle, the delay forced on them by having to contest an American fleet on the lake, put their plans to split the colonies off track and eventually led to their defeat at Saratoga. Hawley went on to command a series of ships in Long Island Sound to harass the British. In May 1779, the British command issued an order to capture American General Gold Selleck Silliman, commander of the militia in Fairfield County. He was captured by a British raiding party in Fairfield. To get the general back an exchange was necessary, but the state had no prisoners of sufficient status to offer. That November, Capt. Hawley gathered 20 volunteers from Stratford, who crossed the sound in small boats and captured Thomas Jones, chief justice of the Ministerial Supreme Court of the Crown. -

030321 VLP Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga readies for new season LEE MANCHESTER, Lake Placid News TICONDEROGA — As countered a band of Mohawk Iro- name brought the eastern foothills American forces prepared this quois warriors, setting off the first of the Adirondack Mountains into week for a new war against Iraq, battle associated with the Euro- the territory worked by the voya- historians and educators in Ti- pean exploration and settlement geurs, the backwoods fur traders conderoga prepared for yet an- of the North Country. whose pelts enriched New other visitors’ season at the site of Champlain’s journey down France. Ticonderoga was the America’s first Revolutionary the lake which came to bear his southernmost outpost of the War victory: Fort Ticonderoga. A little over an hour’s drive from Lake Placid, Ticonderoga is situated — town, village and fort — in the far southeastern corner of Essex County, just a short stone’s throw across Lake Cham- plain from the Green Mountains of Vermont. Fort Ticonderoga is an abso- lute North Country “must see” — but to appreciate this historical gem, one must know its history. Two centuries of battle It was the two-mile “carry” up the La Chute River from Lake Champlain through Ticonderoga village to Lake George that gave the site its name, a Mohican word that means “land between the wa- ters.” Overlooking the water highway connecting the two lakes as well as the St. Lawrence and Hudson rivers, Ticonderoga’s strategic importance made it the frontier for centuries between competing cultures: first between the northern Abenaki and south- ern Mohawk natives, then be- tween French and English colo- nizers, and finally between royal- ists and patriots in the American Revolution. -

Valcour Primitive Area

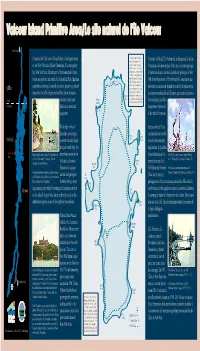

Chambly Canal L’île Valcour comporte 12 km de Comprised of 1,100 acres, Valcour Island is the largest island sentiers de randonnée et 25 Couvrant 4,45 km2, l’île Valcour est la plus grande île du lac emplacements de camping on the New York side of Lake Champlain. It is managed by désignés. Des permis de camping Champlain, côté new-yorkais. Cette zone de nature protégée gratuits d’une durée maximale de the New York State Department of Environmental Conser- 14 jours sont émis par un gardien à l’intérieur du parc des Adirondacks est gérée par le New du parc. Par ailleurs, le site ayant vation as a primitive area within the Adirondack Park. Emphasis adopté le principe du premier York State Department of Environmental Conservation qui is placed on restoring its natural condition, preserving cultural arrivé, premier servi, aucune réser- préconise la restauration du milieu naturel et la préservation Quebec vation n’est acceptée. Pour de plus resources, and affording recreation that does not require amples renseignements sur l’île des ressources culturelles de l’île ainsi que les activités récréa- Beauty Valcour, veuillez communiquer Bay avec le Department of Environmen- Canada extensive man-made Valcour tives n’exigeant pas d’am- Landing tal Conservation au (518) 897-1200. United States facilities or motorized énagements importants equipment. ni de matériel motorisé. With eight miles of Avec sa côte de 13 km shoreline, consisting of constituée d’une variété Spoon Spoon New York a variety of rocky ledges Bay Island de corniches rocheuses and quiet sandy bays, the surplombant de paisibles You Are Here Boating along the rocky ledges of Valcour Island at the recreational potential on baies sablonneuses, le “Baby Blues,” similar to scenes found on Valcour Peru turn of the 19th century. -

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PHASE III: Chatham Borough, Chatham Township, Dover, Madison, Montville, Mount Arlington

CULTURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY MORRIS COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PHASE III: Chatham Borough, Chatham Township, Dover, Madison, Montville, Mount Arlington Principal Investigators: Jennifer B. Leynes Kelly E. Wiles Prepared by: RGA, Inc. 259 Prospect Plains Road, Building D Cranbury, New Jersey 08512 Prepared for: Morris County Department of Planning and Public Works, Division of Planning and Preservation Date: October 15, 2015 BOROUGH OF MADISON MUNICIPAL OVERVIEW: THE BOROUGH OF MADISON “THE ROSE CITY” TOTAL SQUARE MILES: 4.2 POPULATION: 15,845 (2010 CENSUS) TOTAL SURVEYED HISTORIC RESOURCES: 136 SITES LOST SINCE 19861: 21 • 83 Pomeroy Road: demolished between 2002-2007 • 2 Garfield Avenue: demolished between 1987-1991 • Garfield Avenue: demolished c. 1987 • Madison Golf Club Clubhouse: demolished 2007 • George Wilder House: demolished 2001 • Barlow House: demolished between 1987-1991 • Bottle Hill Tavern: demolished 1991 • 13 Cross Street: demolished between 1987-1991 • 198 Kings Road: demolished between 1987-1991 • 92 Greenwood Avenue: demolished c. 2013 • Wisteria Lodge: demolished 1988 • 196 Greenwood Avenue: demolished between 2002-2007 • 194 Rosedale Avenue: demolished c. 2013 • C.A. Bruen House: demolished between 2002-2006 • 85 Green Avenue: demolished 2015 • 21, 23, 25 and 63 Ridgedale Avenue in the Ridgedale Avenue Streetscape/Bottle Hill Historic District: demolished c. 2013 • 21 and 23 Cook Avenue in the Ridgedale Avenue Streetscape: demolished between 1995-2002 RESOURCES DOCUMENTED BY HABS/HAER/HALS: • Bottle Hill Tavern (117 Main -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error.