Ssi RL Io RP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Officers of the Executive Board, 1946-2006

Officers of the Executive Board, 1946-2006 2006 H.E. Mr. Andrei Dapkiunas Belarus President H.E. .Mr. Roble Olhaye Djibouti Vice-Presidents H.E. Mr. Iftekhar Ahmed Chowdhury Bangladesh H.E. Mr. Ernesto Araníbar Quiroga Bolivia Mr. Dirk-Jan Nieuwenhuis Netherlands 2005 H.E. Mr. Mehdi Danesh-Yazdi Islamic Republic of Iran President H.E. Mr. Paul Badji Senegal Vice-Presidents Mr. Uladzimir A. Gerus Belarus Ms. Romy Tincopa Peru Ms. Unni Rambøll Norway 2004 President H.E. Mr. Lebohang K. Moleko Lesotho Vice-Presidents Mr. Mehdi Mirafzal Islamic Republic of Iran H.E. Mr. Vsevolod Grigore Republic of Moldova H.E.Mr. Eduardo J. Sevilla Somoza Nicaragua Ms. Diana Rivington Canada 2003 President H.E. Mr. Jenö Staehelin Switzerland Vice-Presidents H.E. Mr. Luis Gallegos Chiriboga Ecuador H.E.Mr. Roman Kirn Slovenia Mr. Salman Al-Farisi Indonesia H.E. Mr. Lebohang K. Moleko Lesotho 2002 President H.E. Mr. Andrés Franco Colombia Vice-Presidents Mr. Olivier Chave Switzerland H.E. Mr. Crispin Grey-Johnson Gambia H.E. Mr. Murari Raj Sharma Nepal Mr. Marius Ion Dragolea Romania 2001 President H.E. Mr. Movses Abelian Armenia Vice-Presidents H.E. Mr. Alounkèo Kittikhoun Lao People's Democratic Republic H.E. Mr. Andrés Franco Colombia Mr. Paul Goa Zoumanigui Guinea Ms. Jacqueline de Lacy Australia 2000 President H.E. Mr. Anwarul Karim Chowdhury Bangladesh Vice-Presidents Ms. Lala Ibrahimova Azerbaijan H.E. Mr. Alberto Salamanca Bolivia Mr. Luc Shillings Netherlands H.E. Mr. Mubarak Hussein Rahmtalla Sudan 1999 President H.E. Prof. Ibrahim A. Gambari Nigeria Vice-Presidents H.E. -

Norrag News 53 Refugees, Displaced Persons and Education

NORRAG REFUGEES, NEWS DISPLACED PERSONS 53 AND EDUCATION: MAY NEW CHALLENGES 2016 FOR DEVELOPMENT AND POLICY NORRAG NEWS 53 MAY 2016 Editorial Address for this Special Issue: Kenneth King, Saltoun Hall, Pencaitland, Scotland, EH34 5DS, UK Email: [email protected] The invaluable support to the Editor by Robert Palmer is very warmly acknowledged. Email: [email protected] Secretariat Address: Michel Carton, Executive Director Email: [email protected] Aude Mellet, Communication Offi cer Email : [email protected] Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies (IHEID), Post Box 136, Rue Rothschild 20, 1211 Geneva 21, Switzerland. NORRAG is supported by: NORRAG is hosted by: NORRAG News 53 is freely available on our website www.norrag.org in May 2016 What is NORRAG? NORRAG is a worldwide, multi-stakeholder network which has been seeking to inform, challenge and infl uence international education and training policies and cooperation for 30 years. Through networking and other forms of cooperation and institutional partnerships, it aims in particular to: • stimulate and disseminate timely, concise, critical analysis and act as an incubator for new ideas • broker knowledge at the interface between research, policy and practice NORRAG’s current programme focuses on the following themes: • Education and training policies in the Agenda 2030 • Global governance of education and training and the politics of data • Urban violence, youth and education • International perspectives on technical and vocational skills development (TVSD) policies and practice For more information, please visit: www.norrag.org What is NORRAG News? NORRAG News is a digital analytical report that is produced twice a year. -

Global Agenda Council Reports 2010 Gl Global Agenda Council O

Global Agenda Council Reports 2010 Global Agenda Council 2010 Reports Global Agenda Council Reports 2010 .weforum.org) ofit; it is tied to no political, no to tied is it ofit; -pr national organization committed to improving the improving committed to organization national The World Economic Forum is an independent an is Forum Economic World The inter partnerships in leaders engaging by world the of state and industry agendas. to shape global, regional in based and 1971, in a foundation as Incorporated is Forum Economic World the Switzerland, Geneva, not-for and impartial partisan or national interests. (www partisan or national interests. Global_Agenda_SRO_Layout 1 13.01.10 10:29 Page3 Global Agenda Council Reports 2010 Summaries of Global Agenda Council Discussions from the Summit on the Global Agenda 2009 Global_Agenda_SRO_Layout 1 13.01.10 10:29 Page4 This publication is also available in electronic form on the World Economic Forum’s website at the following address: The Global Agenda 2010 Web version: www.weforum.org/globalagenda2010 (HTML) The book is also available as a PDF: www.weforum.org/pdf/globalagenda2010.pdf Other specific information on the Network of Global Agenda Councils can be found at the following links: www.weforum.org/globalagenda2010 www.weforum.org/globalagenda2009/interviews www.weforum.org/globalagenda2009/reports www.weforum.org/globalagenda2009/webcasts The opinions expressed and data communicated in this publication are those of Global Agenda Council Members and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Economic Forum. World Economic Forum 91-93 route de la Capite CH-1223 Cologny/Geneva Switzerland Tel.: +41 (0)22 869 1212 Fax: +41 (0)22 786 2744 E-mail: [email protected] www.weforum.org © 2010 World Economic Forum All rights reserved. -

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas R. Bell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Dr. Sabine Wilke, Chair Dr. Richard Block Dr. Eric Ames Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2015 Thomas R. Bell University of Washington Abstract The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas Richard Bell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Sabine Wilke Germanics This dissertation focuses on texts written by four contemporary, German-speaking authors: W. G. Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn and Schwindel. Gefühle, Daniel Kehlmann’s Die Vermessung der Welt, Sybille Lewitscharoff’s Blumenberg, and Peter Handke’s Der Große Fall. The project explores how the texts represent forms of religion in an increasingly secular society. Religious themes, while never disappearing, have recently been reactivated in the context of the secular age. This current societal milieu of secularism, as delineated by Charles Taylor, provides the framework in which these fictional texts, when manifesting religious intuitions, offer a postsecular perspective that serves as an alternative mode of thought. The project asks how contemporary literature, as it participates in the construction of secular dialogue, generates moments of religiously coded transcendence. What textual and narrative techniques serve to convey new ways of perceiving and experiencing transcendence within the immanence felt and emphasized in the modern moment? While observing what the textual strategies do to evoke religious presence, the dissertation also looks at the type of religious discourse produced within the texts. The project begins with the assertion that a historically antecedent model of religion – namely, Friedrich Schleiermacher’s – which is never mentioned explicitly but implicitly present throughout, informs the style of religious discourse. -

COMING INTO LIFE: the Concept of Peacebuilding in the United Nations, from an Agenda for Peace to the Peacebuilding Commission

Fernando Cavalcante COMING INTO LIFE: The concept of peacebuilding in the United Nations, from An Agenda for Peace to the Peacebuilding Commission Tese de Doutoramento em Relações Internacionais – Política Internacional e Resolução de Conflitos apresentada à Faculdade de Economia da Universidade de Coimbra. Coimbra, 2013 Fernando Carlos Cavalcante Barros Rodrigues Coming into life: The concept of peacebuilding in the United Nations, from An Agenda for Peace to the Peacebuilding Commission Tese de Doutoramento em Relações Internacionais — Política Internacional e Resolução de Conflitos apresentada à Faculdade de Economia da Universidade de Coimbra para obtenção do grau de Doutor. Orientadora: Prof. Doutora Paula Duarte Lopes Coimbra, 2013 À minha família. And to peacebuilders everywhere. iii iv Acknowledgements In my first session as a PhD student, I was told that completing a doctoral research was a rewarding, but equally long, tortuous, challenging and solitary experience. I certainly agree, although I would now say that ‘solitary’ is, at a minimum, an inaccurate qualification. Of course, writing a monograph is by definition a lonely endeavour. But doing research, I learned, despite including periods of seemingly unending confinement for writing purposes, is an inherently social practice. It is about making sense of the world(s) in which we live by constantly interpreting ours and others’ experiences. It necessarily requires establishing dialogues and lines of communication with audiences in particular (and often distinct) contexts. And it requires documenting our progress to ensure that others can engage with our interpretations. This thesis represents a partial product of my social experience as a PhD student and a testament to the invaluable support I received from a range of institutions and individuals over the last five years. -

Undivided PDF Version

Japan’s Official Development Assistance White Paper 2011 White Paper Assistance Official Development Japan’s Japan’s Official Development Assistance White Paper 2011 Japan’s International Japan’s Official Development Assistance Japan’s International Cooperation Japan’s Cooperation White Paper 2011 Japan’s International Cooperation Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan’s Official Development Assistance White Paper 2011 Japan’s International Cooperation Ministry of Foreign Affairs Cover Photographs A staff member from the NGO Association for Aid and Relief, Japan distributes relief supplies to a mother and child who were affected by the large- scale drought in the Garissa District of eastern Kenya (Photo: NPO Association for Aid and Relief, Japan) On the deck of a patrol vessel, a Japanese Coast Guard officer gives an explanation to maritime security organization and coast guard members from Asia and the Middle A medical team from Jordan gives aid to residents of East as part of the training “Maritime Law the affected areas in Minamisoma City, Fukushima Enforcement for Asia and MIddle East” Prefecture, following the Great East Japan conducted in Japan Earthquake (Photo: Riho Aihara/JICA) This White Paper can also be viewed on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website (http://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda). In addition to information about official development assistance (ODA) disbursed by Japan, the website also provides a collection of reference materials regarding aid provided by other countries and the activities of international organizations, etc. All titles of individuals given in this White Paper are those current at the time of the applicable event, etc. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

La + Vista En Youtube Amaia Presume Su Nuevo Amor

16/12/2009 20:15 Cuerpo E Pagina 4 Cyan Magenta Amarillo Negro 4 JUEVES 17 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2009 TÍMPANO TRADICIÓN Y VERDAD Lista En septiembre se publicó la lista de Abba,enelSalóndela nominados para acceder al Salón, de la que se han caído finalmente Donna Summer, los estadounidenses Red Fama del Rock and Roll Hot Chili Peppers y Kiss, así como Darlene Love, Jimmy Cliff, Laura El grupo sueco te a nuestro negocio”, dijo el como en su gira de reunión en Nyro y LL Cool J. accederá en marzo al presidente de esa entidad, 2007”. Joel Peresman. “Sus álbumes ‘Selling En- Salón de la Fama junto a gland By The Pound’ y ‘The Se unen otros artistas. ÉXITOS Lamb Lies Down On Broad- Los responsables del Salón way’ son dos de los discos más subrayaron de nuevo en su co- aclamados de la historia del Junto al conocido EFE municado la importancia de rock progresivo”, añadió la grupo que formaron Nueva York, EU Abba, “uno de los grupos que entidad, que también anunció Benny Andersson, más han vendido en la histo- quiénes serán los galardona- Björn Ulvaeus, Agnetha El popular grupo sueco Abba ria de la música pop” y res- dos con el premio especial Fältskog y Anni-Frid se sumará el próximo marzo, ponsables de que Suecia esté Ahmet Ertegun, en memoria Lyngstad también se junto a otros artistas, a los “en el mapa mundial del del cofundador de la discográ- incorporarán las grandes de la música que in- rock”, gracias a los éxitos que fica Atlantic Records. -

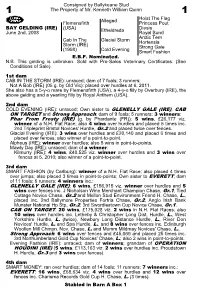

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

Basinskimyersvap B Urns V Ogel S Ieczkowski K a M I N S K I Haukejorgenson B Aus B Rox L Owinger I Ijima D Enrow Taylorsmithtynes S Ikkema Dusie

BASINSKIMYERSVAP B URNS V OGEL S IECZKOWSKI K A M I N S K I HAUKEJORGENSON B AUS B ROX L OWINGER I IJIMA D ENROW TAYLORSMITHTYNES S IKKEMA DUSIE Cover art by Michael Basinski, 2012 ISSUE 13, VOL 4 NO 1 ISSN 1661-6685 For more information about DUSIE PRESS BOOKS and DUSIE the online literary journal, please visit: www.dusie.org/, or contact the editor at [email protected]. DUSIE ZÜRICH 2012 CONTRIBUTORS 6 Introduction 9 Michael Basinski 13 Danielle Vogel 17 Megan Burns 20 Sarah Vap 23 Gina Myers 29 Brenda Sieczkowski 34 Megan Kaminski 38 Nathan Hauke 44 Kirsten Jorgenson 48 Eric Baus 50 Robin Brox 55 Aaron Lowinger 61 Brenda Iijima 64 Jennifer Denrow 69 Shelly Taylor 74 Abraham Smith 79 Jen Tynes 87 Michael Sikkema 93 Contributor Bios 96 DUSIE NEWS In a selection from Lew Welch's Collected Poems, we get a crystal clear look at Radical Vernacular Poetics. I don't have the tech savvy to drum up the lovely zen calligraphy circle that heads the page but the text reads: Step out onto the Planet. Draw a circle a hundred feet round. Inside the circle are 300 things nobody understands, and maybe nobody's ever really seen. How many can you find? Between them, the poets in this issue found all 300 and then some. They found their 300 things on the bus, in hypnosis, on a social work call, listening to Elizabeth Cotton, thinking about Nicki Minaj, contemplating the edges of the mother body, finding ways to let the swamp gas speak, talking straight to the elephants in the room. -

Proceedings of the Members' Assembly

Proceedings:Layout 1 30/03/2009 12:55 Page a Proceedings of the Members’ Assembly World Conservation Congress, Barcelona, 5–14 October 2008 Proceedings:Layout 1 30/03/2009 12:55 Page b “The Congress surpassed all our expectations. In fact, it was a real turning point for us and we now talk of life before the Congress and life after the Congress.” Matías Gómez & Manuel Umpíerrez, young Park Rangers, Uruguay Proceedings:Layout 1 30/03/2009 12:55 Page i Proceedings of the Members’ Assembly World Conservation Congress, Barcelona, 5–14 October 2008 Proceedings:Layout 1 30/03/2009 12:55 Page ii Proceedings:Layout 1 30/03/2009 12:55 Page iii Proceedings of the Members’ Assembly World Conservation Congress, Barcelona, 5–14 October 2008 Compiled and edited by Tim Jones Chief Rapporteur to the Barcelona Congress Proceedings:Layout 1 30/03/2009 12:55 Page iv The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2009 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. -

Inside Spain 54

Inside Spain 54 William Chislett Foreign Policy Spain Offers to Take Guantánamo Prisoners The Spanish Foreign Minister, Miguel Ángel Moratinos, has told the US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, that Spain is prepared to take some of the inmates released from the Guantánamo Bay military camp. Moratinos met Clinton in Washington and said Spain would consider taking prisoners on a case-by-case basis and only under acceptable legal conditions. President Barack Obama is committed to closing the camp by January 2010. As well as pulling out in 2004 the 1,300 peace keeping troops sent to Iraq by José María Aznar, the former Prime Minister, Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero has been a vocal critic of Guantánamo. Just as Rodríguez Zapatero’s withdrawal of the troops strained relations with the US (Zapatero was one of the very few EU heads of government never invited to the White House by George W. Bush), helping the Obama Administration resolve the controversial Guantánamo issue would earn him kudos in Washington. ‘We are prepared to cooperate’, said Moratinos. ‘Our teams will make contact to legally study each case’. Some of the prisoners are expected to face trial in the US. Others cleared for release would need to be moved to third countries as their home nations cannot provide sufficient guarantees of safety as they have poor human-rights records. The Obama Administration is hoping that Rodríguez Zapatero will strengthen Spain’s military presence in Afghanistan, where it currently has close to 800 peacekeeping troops under a United Nations mandate and with tight rules of engagement.