Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrorism and the Media (Including the Internet): an Extensive Bibliography

Perspectives on Terrorism Volume 7, Issue 1, Supplement Terrorism and the Media (including the Internet): an Extensive Bibliography Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes Introduction This bibliography is intended to serve as an extensive up-to-date resource for studying and researching the multi-faceted relationships between terrorism and the media, including the Internet. It contains over 2.200 records covering academic or professional journal articles (most of them peer-reviewed), book chapters, reports, conference contributions, books, theses and other text publications, mainly in English and German. To keep the bibliography manageable, smaller, more informal publications, e.g., blog posts, research briefs, commentaries, newspaper articles, or newsletters, were not considered – with a few exceptions of contributions containing ideas or subjects that were underrepresented in long-form academic or professional literature. The vast majority of resources included date from the 21st century, as after 9/11 – the biggest single media event in history – the amount of publications on the relationship between terrorism and the media has increased considerably. However, terrorist use of the media is as old as terrorism itself and has been researched since the beginning of terrorism studies. Therefore, this bibliography is not restricted to a particular time period and covers publications up to early February 2013. Thematically, the bibliography covers many aspects of the relationship between terrorism and the media, including these: • terrorist use of the traditional media (TV, radio, newspapers); • terrorist use of the new media, especially the Internet (E-Jihad, Cyberterrorism); • online radicalization; • 9/11 as a media event; • media-oriented counter-terrorism measures; • the psychological impact of media exposure to terrorist attacks; • the portrayal of Islam and Muslims after 9/11; • the depiction of terrorism in literature, movies and the arts; • media-oriented hostage-takings. -

The Erosion of Strategic Stability and the Future of Arms Control in Europe

Études de l’Ifri Proliferation Papers 60 THE EROSION OF STRATEGIC STABILITY AND THE FUTURE OF ARMS COntrOL IN EUROPE Corentin BRUSTLEIN November 2018 Security Studies Center The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 978-2-36567-932-9 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2018 How to quote this document: Corentin Brustlein, “The Erosion of Strategic Stability and the Future of Arms Control in Europe”, Proliferation Papers, No. 60, November 2018. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE Tel.: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 – Fax: +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Author Dr. Corentin Brustlein is the Director of the Security Studies Center at the French Institute of International Relations. His work focuses on nuclear and conventional deterrence, arms control, military balances, and U.S. and French defense policies. Before assuming his current position, he had been a research fellow at Ifri since 2008 and the head of Ifri’s Deterrence and Proliferation Program since 2010. -

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British Courage and Capability Might Not Have Been Enough to Win; German Mistakes Were Also Key

How the Luftwaffe Lost the Battle of Britain British courage and capability might not have been enough to win; German mistakes were also key. By John T. Correll n July 1940, the situation looked “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall can do more than delay the result.” Gen. dire for Great Britain. It had taken fight on the landing grounds, we shall Maxime Weygand, commander in chief Germany less than two months to fight in the fields and in the streets, we of French military forces until France’s invade and conquer most of Western shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, predicted, “In three weeks, IEurope. The fast-moving German Army, surrender.” England will have her neck wrung like supported by panzers and Stuka dive Not everyone agreed with Churchill. a chicken.” bombers, overwhelmed the Netherlands Appeasement and defeatism were rife in Thus it was that the events of July 10 and Belgium in a matter of days. France, the British Foreign Office. The Foreign through Oct. 31—known to history as the which had 114 divisions and outnumbered Secretary, Lord Halifax, believed that Battle of Britain—came as a surprise to the Germany in tanks and artillery, held out a Britain had lost already. To Churchill’s prophets of doom. Britain won. The RAF little longer but surrendered on June 22. fury, the undersecretary of state for for- proved to be a better combat force than Britain was fortunate to have extracted its eign affairs, Richard A. “Rab” Butler, told the Luftwaffe in almost every respect. -

The Foundations of US Air Doctrine

DISCLAIMER This study represents the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Air University Center for Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education (CADRE) or the Department of the Air Force. This manuscript has been reviewed and cleared for public release by security and policy review authorities. iii Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Watts, Barry D. The Foundations ofUS Air Doctrine . "December 1984 ." Bibliography : p. Includes index. 1. United States. Air Force. 2. Aeronautics, Military-United States. 3. Air warfare . I. Title. 11. Title: Foundations of US air doctrine . III. Title: Friction in war. UG633.W34 1984 358.4'00973 84-72550 355' .0215-dc 19 ISBN 1-58566-007-8 First Printing December 1984 Second Printing September 1991 ThirdPrinting July 1993 Fourth Printing May 1996 Fifth Printing January 1997 Sixth Printing June 1998 Seventh Printing July 2000 Eighth Printing June 2001 Ninth Printing September 2001 iv THE AUTHOR s Lieutenant Colonel Barry D. Watts (MA philosophy, University of Pittsburgh; BA mathematics, US Air Force Academy) has been teaching and writing about military theory since he joined the Air Force Academy faculty in 1974 . During the Vietnam War he saw combat with the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing at Ubon, Thailand, completing 100 missions over North Vietnam in June 1968. Subsequently, Lieutenant Colonel Watts flew F-4s from Yokota AB, Japan, and Kadena AB, Okinawa. More recently, he has served as a military assistant to the Director of Net Assessment, Office of the Secretary of Defense, and with the Air Staff's Project CHECKMATE. -

Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University

INCENDIARY WARS: The Transformation of United States Air Force Bombing Policy in the WWII Pacific Theater Gilad Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University Faculty Advisor: Professor Mark Mazower Second Reader: Professor Alan Brinkley INCENDIARY WARS 1 Note to the Reader: For the purposes of this essay, I have tried to adhere to a few conventions to make the reading easier. When referring specifically to a country’s aerial military organization, I capitalize the name Air Force. Otherwise, when simply discussing the concept in the abstract, I write it as the lower case air force. In accordance with military standards, I also capitalize the entire name of all code names for operations (OPERATION MATTERHORN or MATTERHORN). Air Force’s names are written out (Twentieth Air Force), the bomber commands are written in Roman numerals (XX Bomber Command, or simply XX), while combat groups are given Arabic numerals (305th Bomber Group). As the story shifts to the Mariana Islands, Twentieth Air Force and XXI Bomber Command are used interchangeably. Throughout, the acronyms USAAF and AAF are used to refer to the United States Army Air Force, while the abbreviation of Air Force as “AF” is used only in relation to a numbered Air Force (e.g. Eighth AF). Table of Contents: Introduction 3 Part I: The (Practical) Prophets 15 Part II: Early Operations Against Japan 43 Part III: The Road to MEETINGHOUSE 70 Appendix 107 Bibliography 108 INCENDIARY WARS 2 Introduction Curtis LeMay sat awake with his trademark cigar hanging loosely from his pursed ever-scowling lips (a symptom of his Bell’s Palsy, not his demeanor), with two things on his mind. -

Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships – 2019 Annual Report

ICC IMB Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships – 2019 Annual Report p ICC INTERNATIONAL MARITIME BUREAU PIRACY AND ARMED ROBBERY AGAINST SHIPS REPORT FOR THE PERIOD 1 January – 31 December 2019 WARNING The information contained in this document is for the internal use of the recipient only. Unauthorised distribution of this document, and/or publication (including publication on a Web site) by any means whatsoever is an infringement of the Bureau’s copyright. ICC International Maritime Bureau Cinnabar Wharf 26 Wapping High Street London E1W 1NG United Kingdom Tel: +44 207 423 6960 Fax: +44 207 423 6961 Email: [email protected] Web: www.icc-ccs.org January 2020 1 ICC IMB Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships – 2019 Annual Report INTRODUCTION The ICC International Maritime Bureau (IMB) is a specialised division of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). The IMB is a not-for-profit organisation, established in 1981 to act as a focal point in the fight against all types of maritime crime and malpractice. The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) in its resolution A 504 (XII) (5) and (9) adopted on 20 November 1981, has inter alia, urged governments, stakeholders and organisation to co-operate and exchange information with each other, and the IMB, with a view of maintaining and developing a coordinated action in combating maritime fraud. This report is an analysis of world-wide reported incidents of piracy and armed robbery against ships from 1 January to 31 December 2019. Outrage in the shipping industry at the alarming growth in piracy prompted the creation of the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre (PRC) in October 1992 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. -

Korea and Vietnam: Limited War and the American Political System

Korea and Vietnam: Limited War and the American Political System By Larry Elowitz A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1972 To Sharon ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express his very deep appreciation to Dr. John W. Spanier for his valuable advice on style and structure. His helpful suggestions were evident throughout the entire process of writing this dissertation. Without his able supervision, the ultimate completion of this work would have been ex- ceedingly difficult. The author would also like to thank his wife, Sharon, whose patience and understanding during the writing were of great comfort. Her "hovering presence," for the "second" time, proved to be a valuable spur to the author's research and writing. She too, has made the completion of this work possible. The constructive criticism and encouragement the author has received have undoubtedly improved the final product. Any shortcomings are, of course, the fault of the author. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES viii ABSTRACT xii CHAPTER 1 THE AMERICAN POLITICAL SYSTEM AND LIMITED WAR 1 Introduction 1 American Attitudes 6 Analytical Framework 10 Variables and Their Implications 15 2 PROLOGUE--A COMPARISON OF THE STAKES IN THE KOREAN AND VIETNAM WARS 22 The External Stakes 22 The Two Wars: The Specific Stakes. 25 The Domino Theory 29 The Internal Stakes 32 The Loss of China Syndrome: The Domestic Legacy for the Korean and Vietnam Wars 32 The Internal Stakes and the Eruption of the Korean War 37 Vietnam Shall Not be Lost: The China Legacy Lingers 40 The Kennedy and Johnson Administra- tions: The Internal Stakes Persist . -

The Ancient Greek Trireme: a Staple of Ancient Maritime Tradition

Wright State University CORE Scholar Classics Ancient Science Fair Religion, Philosophy, and Classics 2020 The Ancient Greek Trireme: A staple of Ancient Maritime Tradition Joseph York Wright State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ancient_science_fair Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Military History Commons Repository Citation York , J. (2020). The Ancient Greek Trireme: A staple of Ancient Maritime Tradition. Dayton, Ohio. This Poster is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion, Philosophy, and Classics at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Ancient Science Fair by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Origin of the Trireme: The Ancient Greek Trireme: A staple of Ancient Maritime Tradition The Trireme likely evolved out of the earlier Greek ships such as the earlier two decked biremes often depicted in a number of Greek pieces of pottery, according to John Warry. These ships depicted in Greek pottery2 were sometimes show with or without History of the Trireme: parexeiresia, or outriggers. The invention of the Trireme is attributed The Ancient Greek Trireme was a to the Sidonians according to Clement staple ship of Greek naval warfare, of Alexandria in the Stromata. and played a key role in the Persian However, Thucydides claims that the Wars, the creation of the Athenian Trireme was invented by the maritime empire, and the Corinthians in the late 8th century BC. -

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas R. Bell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Dr. Sabine Wilke, Chair Dr. Richard Block Dr. Eric Ames Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2015 Thomas R. Bell University of Washington Abstract The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas Richard Bell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Sabine Wilke Germanics This dissertation focuses on texts written by four contemporary, German-speaking authors: W. G. Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn and Schwindel. Gefühle, Daniel Kehlmann’s Die Vermessung der Welt, Sybille Lewitscharoff’s Blumenberg, and Peter Handke’s Der Große Fall. The project explores how the texts represent forms of religion in an increasingly secular society. Religious themes, while never disappearing, have recently been reactivated in the context of the secular age. This current societal milieu of secularism, as delineated by Charles Taylor, provides the framework in which these fictional texts, when manifesting religious intuitions, offer a postsecular perspective that serves as an alternative mode of thought. The project asks how contemporary literature, as it participates in the construction of secular dialogue, generates moments of religiously coded transcendence. What textual and narrative techniques serve to convey new ways of perceiving and experiencing transcendence within the immanence felt and emphasized in the modern moment? While observing what the textual strategies do to evoke religious presence, the dissertation also looks at the type of religious discourse produced within the texts. The project begins with the assertion that a historically antecedent model of religion – namely, Friedrich Schleiermacher’s – which is never mentioned explicitly but implicitly present throughout, informs the style of religious discourse. -

Download Download

10609-04 Auger 2/6/04 10:35 AM Page 47 MARTIN F. AUGER ‘A Tempest in a Teapot’: Canadian Military Planning and the St. Pierre and Miquelon Affair, 1940-1942 THE SMALL FRENCH COLONY OF ST. PIERRE AND MIQUELON, located some 32 kilometers off the south shore of Newfoundland, was a source of great concern for the Canadian government during the Second World War.1 When Nazi Germany defeated France in June 1940, the fate of the French Empire became uncertain. Canada and other Allied countries feared that French colonies might be used by the Germans to conduct military operations against them. The proximity of St. Pierre and Miquelon to Canada and the British colony of Newfoundland constituted a major threat. Negotiations immediately ensued between the American, British and Canadian governments as to the future of France’s territories in the Western Hemisphere. The main argument was whether or not the French islands needed to be occupied by Allied military forces. The issue, however, was solved in December 1941 when the Free French movement of General Charles de Gaulle sent a small naval task force to rally the archipelago to the Allied cause. Most historians who have analyzed the St. Pierre and Miquelon affair of 1940 to 1942 have focused upon the Free French takeover. Although some historians have studied Canada’s role in the affair from a diplomatic perspective, none have provided an in-depth analysis of Canadian military planning during this crisis.2 It is now clear that Canada undertook significant planning to launch an invasion. An understanding of the details of Canada’s invasion plan and the ultimate decision to postpone military action illuminates the changing structure of Canada’s relations with Great Britiain and the United States. -

John Arquilla David Ronfeldt of Engaging in Such Serious Doctrinal Change

SWARMING &The Future of Conflict A New Way of War Swarming is a seemingly amorphous, but deliberately structured, coordinated, strategic way to perform military strikes from all directions. It employs a sustainable pulsing of force and/or fire that is directed from both close-in and stand-off positions. It will work best—perhaps it will only work—if it is designed mainly around the deployment of myriad, small, dispersed, networked maneuver units. This calls for an organizational redesign—involving the creation of platoon-like “pods” joined in company-like “clusters”—that would keep but retool the most basic military unit structures. It is similar to the corporate redesign principle of “flattening,” which often removes or redesigns middle layers of management. This has proven successful in the ongoing revolution in business affairs and may prove equally useful in the military realm. From command and control of line units to logistics, profound shifts will have to occur to nurture this new “way of war.” This study examines the benefits—and also the costs and risks— Arquilla David Ronfeldt John of engaging in such serious doctrinal change. The emergence of a military doctrine based on swarming pods and clusters requires that defense policymakers develop new approaches to connectivity and control and achieve a new balance between the two. Far more than traditional approaches to battle, swarming clearly depends upon robust information flows. Securing these flows, therefore, can be seen as a necessary condition for successful swarming. Related Reading Arquilla, John, and David Ronfeldt, The Advent of Netwar, Santa Monica: RAND, MR-789-OSD, 1996. -

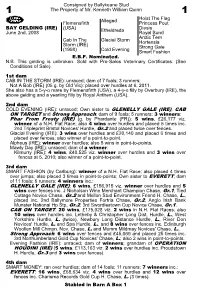

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point.