The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Philosophy of Religion to the History of Religions

CHAPTER ONE FROM THE PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION TO THE HISTORY OF RELIGIONS CHOLARS of religion have devoted little attention to the con- nections between their views of religious history and the phi- Slosophy of religion. Hayden White’s comment that “there can be no ‘proper history’ which is not at the same time ‘philosophy of history’”1 can also be applied to religious history, but that is seldom considered today. On the contrary! Religious studies has taken pains to keep the philosophy of religion far away from its field. Neverthe- less, there is a great deal of evidence for the assertion that the histo- riography of religion was also in fact an implicit philosophy of reli- gion. A search for such qualifications soon yields results, coming up with metahistorical assumptions originating in the philosophy of reli- gion. These sorts of connections have been conscientiously noted by Edward E. Evans-Pritchard, Eric J. Sharpe, Jan de Vries, Jan van Baal, Brian Morris, J. Samuel Preus, and Jacques Waardenburg in their his- tories of the field. Yet, to date, no one has made a serious attempt to apply Hayden White’s comment systematically to research in the field of religious history. But there is every reason to do so. Evidence points to more than simply coincidental and peripheral connections between religious studies as a historical discipline and the philosophy of religion. Perhaps the idea of a history of religions with all its im- plications can be developed correctly only if we observe it from a broader and longer-term perspective of the philosophy of religion. -

Historical Monographs Collection (11 Series)

Historical Monographs Collection (11 Series) Now available in 11 separate thematic series, ATLA Historical Monographs Collection provides researchers with over 10 million pages and 29,000 documents focused on religious thought and practice. The content dates from the 13th century through 1922, with the majority of documents originating from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Biblical Research Perspectives, 1516 - 1922 profiles how biblical studies grew with critical tools and the discovery of ancient manuscript materials. The Historical Critical Method radically transformed how people viewed scriptural texts, while manuscript discoveries like the Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus transformed how scholars and lay people viewed sacred texts. Catholic Engagements with the Modern World, 1487 - 1918 profiles the teaching and practices of the Catholic Church in the modern era. The collection features a broad range of subjects, including Popes and Papacy, Mary, Modernism, Catholic Counter-Reformation, the Oxford Movement, and the Vatican I ecumenical council. Christian Preaching, Worship, and Piety, 1559 - 1919 reflects how Christians lived out their faith in the form of sermons, worship, and piety. It features over 700 texts of either individual or collected sermons from over 400 authors, including Lyman Beecher, Charles Grandison Finney, Friedrich Schleiermacher, and Francis Xavier Weninger. Global Religious Traditions, 1760 - 1922 profiles many living traditions outside of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It addresses theology, philosophy, -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

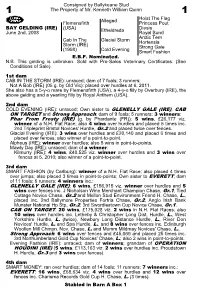

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

Literary and Cultural Translata Bility: the European Romantic Example

Literary and Cultural Translata bility: The European Romantic Example Ian Fairly Abstract This essay presents an overview of Western and Central European thinking about translation in the Romantic period of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In it, I seek to delineate a convergence of aesthetic and cultural theory in the Romantic preoccupation with translation. Among other things, my discussion is interested in how translation in this period engages debate about what it means to be a ‘national’ writer creating a ‘national’ literature. I offer this essay in the hope that its meditation on literary and cultural translatability and untranslatability will resonate with readers in their own quite different contexts. One of the central statements on translation by a British Romantic writer occurs in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Biographia Literaria (1817). Reflecting on the achievements of Wordsworth's verse, Coleridge proposes that the " infallible test of a blameless style " in poetry is " its untranslatableness in words of the same language without injury to the meaning ". This is at once a prescription for fault-finding and an index of immaculacy. A utopian strain sounds through Coleridge's " infallible " and " blameless ", suggesting that an unfallen integrity may be remade, or critically rediscovered, in the uniqueness of poetic utterance. Translation Today Vol. 2 No. 2 Oct. 2005 © CIIL 2005 Literary and Cultural Translata bility: 93 The European Romantic Example Where Wordsworth's " meditative pathos " and " imaginative power " are expressed in verse which cannot be other than it is Coleridge asserts a vital congruence between the particular and the universal. Yet his formula does not preclude the translational recovery of that expressive pathos and power in words of another language. -

Basinskimyersvap B Urns V Ogel S Ieczkowski K a M I N S K I Haukejorgenson B Aus B Rox L Owinger I Ijima D Enrow Taylorsmithtynes S Ikkema Dusie

BASINSKIMYERSVAP B URNS V OGEL S IECZKOWSKI K A M I N S K I HAUKEJORGENSON B AUS B ROX L OWINGER I IJIMA D ENROW TAYLORSMITHTYNES S IKKEMA DUSIE Cover art by Michael Basinski, 2012 ISSUE 13, VOL 4 NO 1 ISSN 1661-6685 For more information about DUSIE PRESS BOOKS and DUSIE the online literary journal, please visit: www.dusie.org/, or contact the editor at [email protected]. DUSIE ZÜRICH 2012 CONTRIBUTORS 6 Introduction 9 Michael Basinski 13 Danielle Vogel 17 Megan Burns 20 Sarah Vap 23 Gina Myers 29 Brenda Sieczkowski 34 Megan Kaminski 38 Nathan Hauke 44 Kirsten Jorgenson 48 Eric Baus 50 Robin Brox 55 Aaron Lowinger 61 Brenda Iijima 64 Jennifer Denrow 69 Shelly Taylor 74 Abraham Smith 79 Jen Tynes 87 Michael Sikkema 93 Contributor Bios 96 DUSIE NEWS In a selection from Lew Welch's Collected Poems, we get a crystal clear look at Radical Vernacular Poetics. I don't have the tech savvy to drum up the lovely zen calligraphy circle that heads the page but the text reads: Step out onto the Planet. Draw a circle a hundred feet round. Inside the circle are 300 things nobody understands, and maybe nobody's ever really seen. How many can you find? Between them, the poets in this issue found all 300 and then some. They found their 300 things on the bus, in hypnosis, on a social work call, listening to Elizabeth Cotton, thinking about Nicki Minaj, contemplating the edges of the mother body, finding ways to let the swamp gas speak, talking straight to the elephants in the room. -

Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine

A HOUSE BUILT ON SAND: Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine E. Taylor Francis Major, USAF Air University James B. Hecker, Lieutenant General, Commander and President LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education Brad M. Sullivan, Major General, Commander AIR UNIVERSITY LEMAY CENTER FOR DOCTRINE DEVELOPMENT AND EDUCATION A House Built on Sand: Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine E. Taylor Francis, Major, USAF Lemay Paper No. 6 Air University Press Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Air University Commander and President Accepted by Air University Press May 2019 and published April 2020. Lt Gen James B. Hecker Commandant and Dean, LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education Maj Gen Brad Sullivan Director, Air University Press Lt Col Darin M. Gregg Project Editor Dr. Stephanie Havron Rollins Illustrator Daniel Armstrong Print Specialist Megan N. Hoehn Distribution Diane Clark Disclaimer Air University Press Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied 600 Chennault Circle, Building 1405 within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily repre- Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6010 sent the official policy or position of the organizations with which https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AUPress/ they are associated or the views of the Air University Press, LeMay Center, Air University, United States Air Force, Department of Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AirUnivPress Defense, or any other US government agency. This publication is cleared for public release and unlimited distribution. and This LeMay Paper and others in the series are available electronically Twitter: https://twitter.com/aupress at the AU Press website: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AUPress/ LeMay-Papers/. -

Information for Schleiermacher's on Religion Eric Watkins Humanities 4

Information for Schleiermacher’s On Religion Eric Watkins Humanities 4 UCSD Friedrich Schleiermacher is the most important Protestant theologian of the period and is a major proponent of Romanticism. In On Religion he articulates his own conception of religion, against Enlightenment conceptions of religion (such as Kant’s) and against conceptions of Romanticism (like Schiller’s) that do not attribute any significant role to religion (or religious experience). Rather than thinking that one should simply focus on being a good person by doing one’s duty (and hope that God will reward good behavior in an afterlife, if there is one), Schleiermacher thinks that religion is essentially about one’s personal immediate relation to a higher power, the infinite, or God, which he identifies with Nature as a whole. Historical and Intellectual Background: •Kant emphasized the importance of morality and thought that whatever was important about religion could be reduced to morality. So to be a genuine Christian would require not that one have just the right theological beliefs (e.g., about transubstantiation or the trinity), but rather that one act according to the Categorical Imperative. The Kingdom of Ends formulation of the Categorical Imperative is, in effect, a religious expression of the moral law, but the religious connotations are not essential to his basic idea, which is most fundamentally secular (because based solely on reason, which is the same for everyone, regardless of their religious beliefs). Kant coins an interesting phrase in referring to “the invisible church”; the idea is that what matters is not the physical buildings that one might worship in, but rather the moral relations that obtain between free rational agents (and which generate our obligations not to lie, harm others, commit suicide, etc.). -

The Property of Mr. Laurence Curran Danehill Danzig Razyana Spartacus

1 The Property of Mr. Laurence Curran 1 Danzig Danehill Razyana Spartacus (IRE) Ogygian BAY FILLY (IRE) Teslemi April 7th, 2008 Martha Queen (Third Produce) Danzig Queen For A Emperor Jones Qui Royalty Day (GB) Nomination (1997) Could Have Been Paulistana E.B.F. Nominated. 1st dam QUEEN FOR A DAY (GB): 3 wins at 4 and £22,741 and placed 10 times; dam of 2 previous foals: Tocatchaprince (IRE) (06 c. by Catcher In The Rye (IRE)): 3-y-o unraced to date. 2nd dam COULD HAVE BEEN (GB): unraced; dam of 5 foals; 5 runners; 2 winners inc.: Queen For A Day (GB): see above. 3rd dam PAULISTANA (USA) (by Pretense): placed 4 times at 2 and 3 in France and 53,600 fr.; dam of 11 foals; 8 runners; 6 winners inc.: POLYTAIN (FR): 3 wins at 3 in France and 2,775,000 fr. inc. Prix du Jockey Club Lancia, Gr.1, placed 3 times viz. 2nd Prix Niceas, L., 3rd Prix d'Harcourt, Gr.2 and Prix La Force, Gr.3; sire. Rajahmundry (USA): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and in U.S.A. and £53,053 and placed 9 times inc. 2nd Drumtop S., L. and Golden Poppy H. Palavera (FR): 2 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed 3 times inc. 3rd Prix Contessina, L.; dam of winners inc.: PALACOONA (FR): won Prix Finlande, L., 3rd Prix Vanteaux, Gr.3 and Prix Ronde de Nuit, L.; dam of DIAMOND TYCOON (USA) (won Fair Grounds H., Gr.3 and 2nd Totesport Spring Trophy, L.), CASSIQUE LADY (IRE) (3 wins at 3 and 4, 2009 and £58,968 inc. -

Master of Arts

Pionius as Martvr and Orator: A Study of the Martyrdom of Pionius by Samantha L. Pascoe A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Religion University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright @ 2007 by Samantha L. Pascoe THE UNTVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STIIDIES COPYRIGHT PERMISSION Pionius as Martyr and Orator: A Study of the Martyrdom of Pioníus BY Samantha L. Pascoe A Thesis/Practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree MASTER OF ARTS Samantha L. Pascoe @ 2007 Permission has been granted to the University of Manitoba Libraries to lend a copy of this thesis/practicum, to Library and Archives Canada (LAC) to lend a copy of this thesis/practicum, and to LAC's agent (UMlÆroQuest) to microfilm, sell copies and to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. ABSTRACT This study investigates how martyría, as well as the acts of martyrdom, functioned for the Christian community in a similar manner to the Roman edicts and decrees. Through a critical evaluation of The Martyrdom of Pionius the Presbyter and his Companions as a case study, the focus of the investigation is on notions of writing and writing with the body as a means to create an individual and cultural memory. -

“I Have Never Seen the Like Before”

“I Have Never Seen the Like Before” Herbst Woods, July 1, 1863 D. Scott Hartwig Of the 160 acres that John Herbst farmed during the summer of 1863, 18 were in a woodlot on the northwestern boundary, adjacent to the farm owned by Edward McPherson. Until July 1, 1863 these woods provided shade for Herbst’s eleven head of cattle, wood for various needs around the farm, and some income. Because of the level of human and animal activity in these woods they were free of undergrowth, except for where they came up against Willoughby Run, a sluggish stream that meandered along their western border. Along this stream willows and brush grew thickly.1 Although Confederate troops passed down the Mummasburg road on June 26 on their way to Gettysburg, either Herbst’s farm was too far off the path of their march, or he was clever about hiding his livestock, for he suffered no losses. His luck at avoiding damage or loss from the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania began to run out on June 30. It was known that a large force of Confederates had occupied Cashtown on June 29, causing a stir of uneasiness. William Comfort and David Finnefrock, the tenant farmers on the Emmanuel Harmon farm, Herbst’s neighbor west of Willoughby Run, chose to take their horses away to protect them. Herbst and John Slentz, the tenant who farmed the McPherson farm, apparently decided to try their chances and remained on their farms, thinking they stood a better chance of protecting their property if they remained.2 On the morning of June 30 a large Confederate infantry brigade under the command of General James J.