Master of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAT101 Booklet.Pdf

Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States PAT 102 NICENE AND POST NICENE FATHERS Servants’ Preparation Program 2007 ( TABLE OF CONTENTS ( • Introduction • The Beginnings of Liturgical Formulas and Canonical Legislation • The Apostolic Fathers • St. Clement of Rome • St. Ignatius of Antioch • St. Polycarp of Smyrna • The Epistle of Barnabas • Papias of Hierapolis • The "Shepherd" of Hermas • The Epistle to Diognetus • QUADRATUS 2 PAT 102 Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers © 2007 Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States INTRODUCTION Patrology The word “Patrology” is derived from the Latin word “Pater” which means, “Father.” Patrology is the science, which deals with the life, acts, writings, sayings, doctrines and thoughts of the orthodox writers of the early church: 1) The life of the Fathers: In order to understand their writings and sayings, their lives and the environment in which they lived, must also be considered. 2) Their acts: The writings, sermons, dialogues, letters, etc. of the Fathers are inseparable from their own lives. Patrology’s message is to be sure of the authenticity of these acts scientifically, publishing them and translating them in modern languages. 3) More importantly is the discovery of the thoughts of the Fathers, their dogma, doctrines and concepts concerning God, man, church, salvation, worship, creation, the body, the heavenly life, etc. Patrology is the door through which we can enter into the church and attain her spirit, which affects our inner life, conduct and behavior. Through Patrology, the acts of the Fathers are transferred into living thoughts and concepts which are based on a sound foundation, without ignoring the world around us. -

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas R. Bell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Dr. Sabine Wilke, Chair Dr. Richard Block Dr. Eric Ames Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2015 Thomas R. Bell University of Washington Abstract The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas Richard Bell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Sabine Wilke Germanics This dissertation focuses on texts written by four contemporary, German-speaking authors: W. G. Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn and Schwindel. Gefühle, Daniel Kehlmann’s Die Vermessung der Welt, Sybille Lewitscharoff’s Blumenberg, and Peter Handke’s Der Große Fall. The project explores how the texts represent forms of religion in an increasingly secular society. Religious themes, while never disappearing, have recently been reactivated in the context of the secular age. This current societal milieu of secularism, as delineated by Charles Taylor, provides the framework in which these fictional texts, when manifesting religious intuitions, offer a postsecular perspective that serves as an alternative mode of thought. The project asks how contemporary literature, as it participates in the construction of secular dialogue, generates moments of religiously coded transcendence. What textual and narrative techniques serve to convey new ways of perceiving and experiencing transcendence within the immanence felt and emphasized in the modern moment? While observing what the textual strategies do to evoke religious presence, the dissertation also looks at the type of religious discourse produced within the texts. The project begins with the assertion that a historically antecedent model of religion – namely, Friedrich Schleiermacher’s – which is never mentioned explicitly but implicitly present throughout, informs the style of religious discourse. -

Female Identity and Agency in the Cult of the Martyrs in Late Antique North Africa

Female Identity and Agency in the Cult of the Martyrs in Late Antique North Africa Heather Barkman Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For admission to the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Religious Studies Department of Classics and Religious Studies Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Heather Barkman, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ii Abstract iv Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Outline of the Chapters 9 Identity, Agency, and Power: Women’s Roles in the Cult of the Martyrs 14 Methodology 14 i. Intermittent Identities 14 ii. Agency 23 iii. Power 28 Women’s Roles 34 Wife 35 Mother 40 Daughter 43 Virgin 49 Mourner 52 Hostess 56 Widow 59 Prophet 63 Patron 66 Martyr 71 Conclusion 75 Female Martyrs and the Rejection/Reconfiguration of Identities 78 Martyrdom in North Africa 80 Named North African Female Martyrs 87 i. Januaria, Generosa, Donata, Secunda, Vestia (Acts of the Scillitan Martyrs) 87 ii. Perpetua and Felicitas (Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas) 87 iii. Quartillosa (Martyrdom of Montanus and Lucius) 89 iv. Crispina (Passion of Crispina) 90 v. Maxima, Donatilla, and Secunda (Passion of Saints Maxima, Donatilla, and Secunda) 91 vi. Salsa (Passion of Saint Salsa) 92 vii. Victoria, Maria, and Januaria (Acts of the Abitinian Martyrs) 93 Private Identities of North African Female Martyrs 95 Wife 95 Mother 106 Daughter 119 Private/Public Identities of North African Female Martyrs 135 Virgin 135 Public Identities of North African Female Martyrs 140 Bride of Christ 141 Prophet 148 Imitator of Christ 158 Conclusion 162 Patrons, Clients, and Imitators: Female Venerators in the Cult of the Martyrs 166 iii Patron 168 Client 175 i. -

Journal of Theological Studies

304 THE JOURNAL OF THEOLOGICAL STUDIES CHRONICLE HAGIOGRAPHICA. THE two years that have eJapsed since the Jut Chronicle of C H.agio graphica' have not witnessed any event of first magnitude in the field of hagiology; the BoIlandists have not issued a volume of the AdlI $aNlo,."" nor has there appeared in the MIJIIIIIM1Ua GentIIUIiaI HisItJri«l any volume of Yilae. For all that, there is a considerable body of good work to record. J. We may begin with a mention of three general Histories ~ Christian Literature, all of first rank, which naturally contain a great quantity of bagiologica1 material: the second volume of Hamack's CImmo/Qgie (Irenaeus to Eusebius); the second volume of Bardeo hewer's (leSt_All Mr allllinldiew Lilenllu,. (cent. iii); and Schanz, Gut_Ne Mr riiltlistllm Li/er'aJu,., of which a second edition of Part Ill, and the first half of Part IV, have recently appeared, both mainly devoted to the Latin Christian writers up to the end of the fourth century. The merits of these three standard works being so well established, it is needless to do more than remind bagiologists that they are mines of information on things bagiologica1. 2. In the domain of Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles, the chief event has without doubt been the publication of Dr Carl Schmidt's long looked-for edition of the Coptic Ada PaIIl; j this, however, has been sufficiently dealt with in previous numbers of the JOURNAL. There is, therefore, here need only to note that Corssen has challenged practically every item of the structure erected by Schmidt on the Coptic fragments t, and that the Bollandist reviewer adopts a position of extreme reserve in regard to the whole question '. -

"Voluntary Martyrdom" and the Martyrs of Lyons

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 8-2016 Zealous until Death: "Voluntary Martyrdom" and the Martyrs of Lyons Matthew R. Anderson Abilene Christian University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Part of the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Matthew R., "Zealous until Death: "Voluntary Martyrdom" and the Martyrs of Lyons" (2016). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 35. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. ABSTRACT For decades, many scholars have been uncomfortable with the idea that some early Christians were eager to die. This led to the creation of the category “voluntary martyrdom” by which modern historians attempted to understand those martyrs who provoked their own arrest and/or death in some fashion. Scholars then connected this form of martyrdom with an early Christian movement called the New Prophecy, which came to be known as Montanism. Thus, scholars have scoured martyr accounts in an attempt to identify volunteers and, in some cases, label them Montanists. The Letter from the Churches of Vienna and Lyons and the martyrs it depicts did not escape such scrutiny. I contend that the martyrs in that account who have been accused of heresy are not only innocent of heresy but also should not be considered volunteers. This study surveys the role of the language of zeal and enthusiasm in the account of the martyrs of Lyons. -

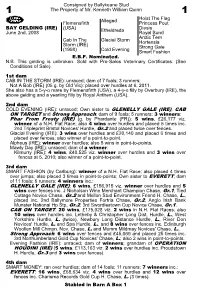

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

FATHERS Church

FOC_TPages 9/12/07 9:47 AM Page 2 the athers Fof the Church A COMPREHENSIVE INTRODUCTION HUBERTUS R. DROBNER Translated by SIEGFRIED S. SCHATZMANN with bibliographies updated and expanded for the English edition by William Harmless, SJ, and Hubertus R. Drobner K Hubertus R. Drobner, The Fathers of the Church Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2007. Used by permission. _Drobner_FathersChurch_MiscPages.indd 1 11/10/15 1:30 PM The Fathers of the Church: A Comprehensive Introduction English translation © 2007 by Hendrickson Publishers Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. P. O. Box 3473 Peabody, Massachusetts 01961-3473 ISBN 978-1-56563-331-5 © 2007 by Baker Publishing Group The Fathers of the Church: A Comprehensive Introduction, by Hubertus R. Drobner, withPublished bibliographies by Baker Academic updated and expanded for the English edition by William Harmless,a division of SJ, Baker and Hubertus Publishing Drobner, Group is a translation by Siegfried S. Schatzmann ofP.O.Lehrbuch Box 6287, der Grand Patrologie. Rapids,© VerlagMI 49516-6287 Herder Freiburg im Breisgau, 1994. www.bakeracademic.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any Baker Academic paperback edition published 2016 formISBN or978-0-8010-9818-5 by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, record- ing, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writingPreviously from published the publisher. in 2007 by Hendrickson Publishers PrintedThe Fathers in the of Unitedthe Church: States A ofComprehensive America Introduction, by Hubertus R. Drobner, with bibliographies updated and expanded for the English edition by William Harmless, SecondSJ, and PrintingHubertus — Drobner, December is a 2008 translation by Siegfried S. -

Basinskimyersvap B Urns V Ogel S Ieczkowski K a M I N S K I Haukejorgenson B Aus B Rox L Owinger I Ijima D Enrow Taylorsmithtynes S Ikkema Dusie

BASINSKIMYERSVAP B URNS V OGEL S IECZKOWSKI K A M I N S K I HAUKEJORGENSON B AUS B ROX L OWINGER I IJIMA D ENROW TAYLORSMITHTYNES S IKKEMA DUSIE Cover art by Michael Basinski, 2012 ISSUE 13, VOL 4 NO 1 ISSN 1661-6685 For more information about DUSIE PRESS BOOKS and DUSIE the online literary journal, please visit: www.dusie.org/, or contact the editor at [email protected]. DUSIE ZÜRICH 2012 CONTRIBUTORS 6 Introduction 9 Michael Basinski 13 Danielle Vogel 17 Megan Burns 20 Sarah Vap 23 Gina Myers 29 Brenda Sieczkowski 34 Megan Kaminski 38 Nathan Hauke 44 Kirsten Jorgenson 48 Eric Baus 50 Robin Brox 55 Aaron Lowinger 61 Brenda Iijima 64 Jennifer Denrow 69 Shelly Taylor 74 Abraham Smith 79 Jen Tynes 87 Michael Sikkema 93 Contributor Bios 96 DUSIE NEWS In a selection from Lew Welch's Collected Poems, we get a crystal clear look at Radical Vernacular Poetics. I don't have the tech savvy to drum up the lovely zen calligraphy circle that heads the page but the text reads: Step out onto the Planet. Draw a circle a hundred feet round. Inside the circle are 300 things nobody understands, and maybe nobody's ever really seen. How many can you find? Between them, the poets in this issue found all 300 and then some. They found their 300 things on the bus, in hypnosis, on a social work call, listening to Elizabeth Cotton, thinking about Nicki Minaj, contemplating the edges of the mother body, finding ways to let the swamp gas speak, talking straight to the elephants in the room. -

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC LETTER ORIENTALE LUMEN OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS, CLERGY AND FAITHFUL TO MARK THE CENTENARY OF ORIENTALIUM DIGNITAS OF POPE LEO XIII Venerable Brothers, Dear Sons and Daughters of the Church 1. The light of the East has illumined the universal Church, from the moment when "a rising sun" appeared above us (Lk 1:78): Jesus Christ, our Lord, whom all Christians invoke as the Redeemer of man and the hope of the world. That light inspired my predecessor Pope Leo XIII to write the Apostolic Letter Orientalium Dignitas in which he sought to safeguard the significance of the Eastern traditions for the whole Church.(1) On the centenary of that event and of the initiatives the Pontiff intended at that time as an aid to restoring unity with all the Christians of the East, I wish to send to the Catholic Church a similar appeal, which has been enriched by the knowledge and interchange which has taken place over the past century. Since, in fact, we believe that the venerable and ancient tradition of the Eastern Churches is an integral part of the heritage of Christ's Church, the first need for Catholics is to be familiar with that tradition, so as to be nourished by it and to encourage the process of unity in the best way possible for each. Our Eastern Catholic brothers and sisters are very conscious of being the living bearers of this 2 tradition, together with our Orthodox brothers and sisters. The members of the Catholic Church of the Latin tradition must also be fully acquainted with this treasure and thus feel, with the Pope, a passionate longing that the full manifestation of the Church's catholicity be restored to the Church and to the world, expressed not by a single tradition, and still less by one community in opposition to the other; and that we too may be granted a full taste of the divinely revealed and undivided heritage of the universal Church(2) which is preserved and grows in the life of the Churches of the East as in those of the West. -

John Foxe and the Joy of Suffering Author(S): John R

John Foxe and the Joy of Suffering Author(s): John R. Knott Source: The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Autumn, 1996), pp. 721-734 Published by: The Sixteenth Century Journal Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2544014 . Accessed: 17/05/2014 21:54 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Sixteenth Century Journal is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Sixteenth Century Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.211.24.157 on Sat, 17 May 2014 21:54:58 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions SixteenthCenturyJournal XXVII/3(1996) John Foxe and theJoy of Suffering JohnR. Knott Universityof Michigan JohnFoxe rejectedthe earlyChristian and medievalemphasis on the exceptional natureof martyrsand on thedisjunction between vulnerable body and transported soul,focusing instead on thehuman qualities of his Protestant martyrs and thecom- munalexperience of thepersecuted faithful, which becomes the locus of thesacred. He avoidedthe miraculous in attemptingto reconcilerepresentations ofhorrific suf- feringwith traditional affirmations ofthe inner peace andjoy ofthe martyr. Much of thedrama of theActs and Monuments arises from intrusions of the ordinary (the gesture ofwiping a sootyhand on a smock)and theunpredictable (a fire that will not burn). -

Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine

A HOUSE BUILT ON SAND: Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine E. Taylor Francis Major, USAF Air University James B. Hecker, Lieutenant General, Commander and President LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education Brad M. Sullivan, Major General, Commander AIR UNIVERSITY LEMAY CENTER FOR DOCTRINE DEVELOPMENT AND EDUCATION A House Built on Sand: Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine E. Taylor Francis, Major, USAF Lemay Paper No. 6 Air University Press Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Air University Commander and President Accepted by Air University Press May 2019 and published April 2020. Lt Gen James B. Hecker Commandant and Dean, LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education Maj Gen Brad Sullivan Director, Air University Press Lt Col Darin M. Gregg Project Editor Dr. Stephanie Havron Rollins Illustrator Daniel Armstrong Print Specialist Megan N. Hoehn Distribution Diane Clark Disclaimer Air University Press Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied 600 Chennault Circle, Building 1405 within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily repre- Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6010 sent the official policy or position of the organizations with which https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AUPress/ they are associated or the views of the Air University Press, LeMay Center, Air University, United States Air Force, Department of Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AirUnivPress Defense, or any other US government agency. This publication is cleared for public release and unlimited distribution. and This LeMay Paper and others in the series are available electronically Twitter: https://twitter.com/aupress at the AU Press website: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AUPress/ LeMay-Papers/. -

Pat 101 – Nicene & Post Nicene Fathers

PAT 101 – NICENE & POST NICENE FATHERS Lecture I What is Patrology? Patrology is derived from Latin word “Pater” which means “Father” Patrology is the science dealing with the life, acts, writings, sayings, doctrines & thoughts of the early fathers. Patrology focuses on ensuring the authenticity of these acts, publishing them and translating them in modern languages. Why Study Patrology? Leads us to a true understanding of Christianity through the works of the early fathers. Reveals to us the circumstances in which the fathers witnessed to Christ. Helps us discover the fathers‟ dogma, doctrines & concepts concerning God, man, church, salvation, eternal life. Etc. Classifications of Patristic Writings Classification by Time Especially first 5 centuries can be classified on Time. First Ecumenical Council (Nicaea) separated fathers into 2 kinds: Ante-Nicene – Simple Literature Nicene & Post Nicene Fathers Classification by Language Greek (Eastern) Fathers Majority of the fathers wrote in Greek. Some also used their national languages such as Coptic, Syrian & Armenian. Latin (Western) Fathers Classification by Place Egyptian Fathers – School of Alexandria & Desert Fathers. Antiochenes Fathers – In Antioch (Turkey) Cappadocian Fathers – In Cappadocia (Asia Minor) Latin Fathers – In Europe Classification by Material Apologetic – defending the faith against critics. Biblico-exegetical – Interpretations/Explanations of the Bible. Homilies & sermons. Letters. Liturgical works. Classification by Material Christian poetry & songs Dialogues Ascetic Writings Church canons Church History Chronological Outline of Patristic Literature The Beginning of Christian Patristic Literature Ante-Nicene Literature after St. Irenaeus. Golden Age of the Eastern Fathers Western Fathers (4th and 5th Centuries) Writings after the Council of Chalcedon Outline of Patristic Literature • Canonical Legislation & liturgical Formulas.