“I Have Never Seen the Like Before”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Local Remembrance on National Narratives of Gettysburg During the 19Th Century

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Contested Narratives: The Influence of Local Remembrance on National Narratives of Gettysburg During The 19th Century Jarrad A. Fuoss Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Fuoss, Jarrad A., "Contested Narratives: The Influence of Local Remembrance on National Narratives of Gettysburg During The 19th Century" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7177. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7177 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Contested Narratives: The Influence of Local Remembrance on National Narratives of Gettysburg During The 19th Century. Jarrad A. Fuoss Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Science at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in 19th Century American History Jason Phillips, Ph.D., Chair Melissa Bingman, Ph.D. Brian Luskey, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2018 Keywords: Gettysburg; Civil War; Remembrance; Memory; Narrative Creation; National Identity; Citizenship; Race; Gender; Masculinity; Veterans. -

A Past So Fraught with Sorrow Bert H

A Past So Fraught With Sorrow Bert H. Barnett, Gettysburg NMP On May 23 and 24, 1865, the victorious Union armies gathered for one massive, final “Grand Review” in Washington, D.C. Among the multitude of patriotic streamers and buntings bedecking the parade route was one, much noticed, hanging from the Capitol. It proclaimed, perhaps with an unintended irony, “The only national debt we can never pay is the debt we owe the victorious Union soldiers.” One sharp-eyed veteran, a participant in almost all the war’s eastern campaigns, observed, “I could not help wondering, whether, having made up their minds that they can never pay the debt, they will not think it useless to try” [emphasis in original].1 The sacrifices demanded of the nation to arrive at that point had been terrific—more than 622,000 men dead from various causes. To acknowledge these numbers simply as a block figure, however, is to miss an important portion of the story. Each single loss represented an individual tragedy of the highest order for thousands of families across the country, North and South. To have been one of the “merely wounded” was often to suffer a fate perhaps only debatably better than that of a deceased comrade. Many of these battle casualties were condemned to years of physical agony and mental duress. The side effects that plagued these men often also tore through their post-war lives and families as destructively as any physical projectile, altering relationships with loved ones and reducing the chances for a fuller integration into a post-war world. -

VOL. XLIII, NO. 8 Michigan Regimental Round Table Newsletter—Page 1 August 2003

VOL. XLIII, NO. 8 Michigan Regimental Round Table Newsletter—Page 1 August 2003 "It wasn't like a battle at all…it was more like Indian warfare," remembered John McClure, a young private in the 14th Indiana Infantry. "I hid behind a tree and looked out. Across the way…was a rebel aiming at me. I put my hat on a stick…and stuck it out from behind the tree-as bait. Then I saw him peep out of the thicket and I shot him. It was the first time I'd ever seen the man I'd killed, and it was an awful feeling." This deadly incident, on May 5, 1864, was only one of such commonplace bloody episodes that occurred in the bitter struggle known as the Wilderness. Beginning in 1864 North and South stood in weary stalemate. All of the Federal victories from the previous year, including Gettysburg and Vicksburg, had seriously weakened the Confederacy, but, it remained bowed, not broken. For the North to win the war, now starting its fourth year, the Confederate armies must be crushed. The South, conversely, had one final hope: stymie the North's plans and count upon a war-weary Northern home front to force the conflict to the peace table. Now in early May of 1864, the two most notable titans of the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, were about to come face-to-face in a final showdown to determine the war's outcome. Grant, whose roller coaster career had nearly ended on several occasions, was given the revitalized rank of Lieutenant General by President Lincoln, and the amazingly difficult task of besting the Army of Northern Virginia, something his predecessors had found nigh impossible. -

Lee's Mistake: Learning from the Decision to Order Pickett's Charge

Defense Number 54 A publication of the Center for Technology and National Security Policy A U G U S T 2 0 0 6 National Defense University Horizons Lee’s Mistake: Learning from the Decision to Order Pickett’s Charge by David C. Gompert and Richard L. Kugler I think that this is the strongest position on which Robert E. Lee is widely and rightly regarded as one of the fin- to fight a battle that I ever saw. est generals in history. Yet on July 3, 1863, the third day of the Battle — Winfield Scott Hancock, surveying his position of Gettysburg, he ordered a frontal assault across a mile of open field on Cemetery Ridge against the strong center of the Union line. The stunning Confederate It is my opinion that no 15,000 men ever arrayed defeat that ensued produced heavier casualties than Lee’s army could for battle can take that position. afford and abruptly ended its invasion of the North. That the Army of Northern Virginia could fight on for 2 more years after Gettysburg was — James Longstreet to Robert E. Lee, surveying a tribute to Lee’s abilities.1 While Lee’s disciples defended his decision Hancock’s position vigorously—they blamed James Longstreet, the corps commander in This is a desperate thing to attempt. charge of the attack, for desultory execution—historians and military — Richard Garnett to Lewis Armistead, analysts agree that it was a mistake. For whatever reason, Lee was reti- prior to Pickett’s Charge cent about his reasoning at the time and later.2 The fault is entirely my own. -

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015

89.1963.1 Iron Brigade Commander Wayne County Marker Text Review Report 2/16/2015 Marker Text One-quarter mile south of this marker is the home of General Solomon A. Meredith, Iron Brigade Commander at Gettysburg. Born in North Carolina, Meredith was an Indiana political leader and post-war Surveyor-General of Montana Territory. Report The Bureau placed this marker under review because its file lacked both primary and secondary documentation. IHB researchers were able to locate primary sources to support the claims made by the marker. The following report expands upon the marker points and addresses various omissions, including specifics about Meredith’s political service before and after the war. Solomon Meredith was born in Guilford County, North Carolina on May 29, 1810.1 By 1830, his family had relocated to Center Township, Wayne County, Indiana.2 Meredith soon turned to farming and raising stock; in the 1850s, he purchased property near Cambridge City, which became known as Oakland Farm, where he grew crops and raised award-winning cattle.3 Meredith also embarked on a varied political career. He served as a member of the Wayne County Whig convention in 1839.4 During this period, Meredith became concerned with state internal improvements: in the early 1840s, he supported the development of the Whitewater Canal, which terminated in Cambridge City.5 Voters next chose Meredith as their representative to the Indiana House of Representatives in 1846 and they reelected him to that position in 1847 and 1848.6 From 1849-1853, Meredith served -

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas R. Bell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Dr. Sabine Wilke, Chair Dr. Richard Block Dr. Eric Ames Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2015 Thomas R. Bell University of Washington Abstract The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas Richard Bell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Sabine Wilke Germanics This dissertation focuses on texts written by four contemporary, German-speaking authors: W. G. Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn and Schwindel. Gefühle, Daniel Kehlmann’s Die Vermessung der Welt, Sybille Lewitscharoff’s Blumenberg, and Peter Handke’s Der Große Fall. The project explores how the texts represent forms of religion in an increasingly secular society. Religious themes, while never disappearing, have recently been reactivated in the context of the secular age. This current societal milieu of secularism, as delineated by Charles Taylor, provides the framework in which these fictional texts, when manifesting religious intuitions, offer a postsecular perspective that serves as an alternative mode of thought. The project asks how contemporary literature, as it participates in the construction of secular dialogue, generates moments of religiously coded transcendence. What textual and narrative techniques serve to convey new ways of perceiving and experiencing transcendence within the immanence felt and emphasized in the modern moment? While observing what the textual strategies do to evoke religious presence, the dissertation also looks at the type of religious discourse produced within the texts. The project begins with the assertion that a historically antecedent model of religion – namely, Friedrich Schleiermacher’s – which is never mentioned explicitly but implicitly present throughout, informs the style of religious discourse. -

Historic Walking Tour

22 At 303 Baltimore St. is the James Pierce family 28 Over a hundred First and Eleventh Corps Union home. After the Civil War, Tillie Pierce Alleman wrote soldiers held much of this block in a pocket of Yankee a riveting account of their experiences, At Gettysburg: resistance on the late afternoon of July 1 as the Or What a Girl Saw and Heard at the Battle. Confederates otherwise took control of the town. Continue north on Baltimore Street to High Street… Historic Walking Tour 29 In 1863, John and Martha Scott and Martha’s sister 23 The cornerstone of the Prince of Peace Episcopal Mary McAllister lived at 43-45 Chambersburg Street. Church was laid on July 2, 1888, for the twenty-fifth John and Martha’s son, Hugh ran a telegraph office here anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. The church is a and fled just prior to the arrival of the Confederates. battlefield memorial for inside the large tower survivors His mother’s red shawl hung from an upstairs window from both armies placed more than 130 plaques in to designate the building as a hospital. memory of their fallen comrades. Continue north on Baltimore Street to Middle Street… 30 The James Gettys Hotel in 1804 was known as the “Sign of the Buck” tavern and roadhouse. During the 24 Here at the Adams County Courthouse on June Civil War, it was known as the Union Hotel, and served 26, 1863, men of the 26th Pennsylvania Emergency as a hospital. Militia, which included local college and seminary students, were paroled by General Jubal Early after 31 Alexander Buehler’s drug and bookstore was located being captured during the Confederate’s initial advance. -

GENERAL STONE's ELEVATED RAILROAD Portrait of an Inventor Mark Reinsberg

GENERAL STONE'S ELEVATED RAILROAD Portrait of an Inventor Mark Reinsberg Part III several months after the close of the Philadelphia Centennial and the dismantling of his monorail exhibit, Roy Stone lived an ForA intensely private life, leaving no documentation whatever. One can imagine that the General returned to Cuba, New York, dis- heartened by the debacle and deeply involved in the problems of bankruptcy. There were health problems as well. Towards the end of winter, 1876/77, Stone resolved to cash in an old IOU. On a gloomy and introspective March day, the General traveled to Belmont, the seat of Allegany County, New York.He did so in order to make a legal declaration, an affidavit needed "for the purpose of being placed on the invalid pension role of the United States/' State of New York County of Allegany ss: On this 12th day of March A.D. 1877 personally appeared before me clerk of said County ... Roy Stone aged forty (40) years, a resident of the village of Cuba ... who being duly sworn according to law declares that he is the identical Roy Stone who was ... Colonel of the 149th Regiment Penna. Vols., and was on the 7th day of September, 1864, made a Bvt. Brig. Genl. U.S. Vols., ... That while a member of the organization aforesaid, to wit Colonel, 149th Regt. P.V. in the service and in the line of his duty at Gettysburg in the State of Penna., on or about the first day of July, 1863, he was wounded in the right hip by a musket ball fired by the enemy. -

ED436450.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 436 450 SO 031 019 AUTHOR Andrews, John TITLE Choices and Commitments: The Soldiers at Gettysburg. Teaching with Historic Places. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. National Register of Historic Places. PUB DATE 1999-06-00 NOTE 23p. AVAILABLE FROM National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places, 1849 C Street, NW, Suite NC400, Washington, DC 20240. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom - Teacher (052)-- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Civil War (United States); *Geography; *Historic Sites; *History Instruction; Middle Schools; *Political Issues; *Primary Sources; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Student Educational Objectives; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Gettysburg Battle; National Register of Historic Places; Pennsylvania ABSTRACT This lesson focuses on the U.S. Civil War Battle of Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) at the beginning of July 1863. The lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Gettysburg Battlefield Historic District," as well as several primary and secondary sources. It could be used with units on the U.S. Civil War or in geography or ethics courses. The lesson considers the actions of the Union and Confederate armies in the Battle of Gettysburg and the personal choices made by some of the participants. Student objectives and a list of materials are given in the lesson's first section, "About This Lesson." The lesson is divided into the following sections: (1) "Setting the Stage: Historical -

Immersed Into History

Immersed into History Experience the Battle of Gettysburg from both sides of the battle lines! DAY ONE Visit the Seminary Ridge Museum and stand on the very grounds where the battle began on July 1, 1863. Look out the very windows Union soldiers used, as the Confederate Army charged the hills. Tour the museum and see artifacts, mini movies and displays of war time experiences. Next a Licensed Guide dressed as a Union soldier will board your group’s bus for a two hour tour of the battlefield. The guides knowledge and expertise will bring the battle to life, as your group tours the hallowed grounds where battle lines were drawn. Enjoy a hearty lunch at the Historic Dobbin House. After lunch, tour the Jennie Wade House Museum. The home where the only civilian was killed during the three day battle. Hear how she lost her life and how her family had to make their way to safety. You will follow the same way the family traveled as the battle raged around them. Check into one of our many group friendly hotels and enjoy another great meal before your last stop of the night, a 90 minute ghost tour with: Ghostly Images of Gettysburg! Return to your hotel to relax after such a History filled day! Immersed into History Experience the Battle of Gettysburg from both sides of the battle lines! DAY TWO Begin your day by visiting the Gettysburg National Military Park Visitor Center, there you will see the Film, Cyclorama and Museum, before diving back into the battlefield. -

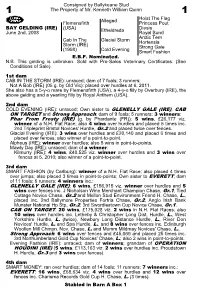

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

Gov. Andrew G. Curtin & the Union's Civil

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2012 For the Hope of Humanity: Gov. Andrew G. Curtin & the Union's Civil War Jared Frederick West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Frederick, Jared, "For the Hope of Humanity: Gov. Andrew G. Curtin & the Union's Civil War" (2012). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4854. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4854 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “For the Hope of Humanity: Gov. Andrew G. Curtin & the Union’s Civil War” Jared Frederick Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Aaron Sheehan-Dean, Ph.D., Chair Brian P. Luskey, Ph.D. Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 20125 Keywords: History, American Civil War, Pennsylvania, Politics, Liberalism Copyright 20125Jared Frederick ABSTRACT “For the Hope of Humanity: Gov.