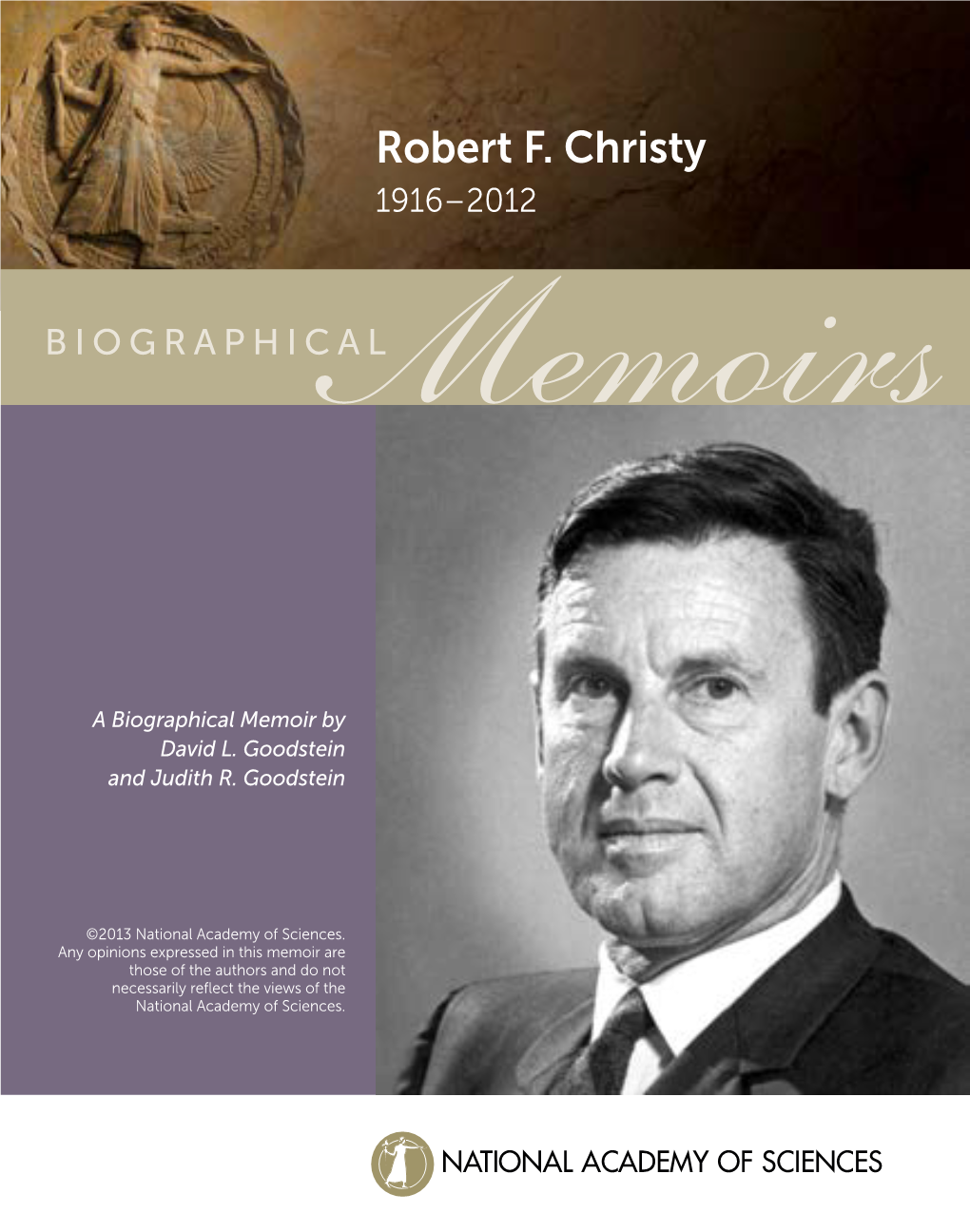

Robert F. Christy 1916–2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simulating Physics with Computers

International Journal of Theoretical Physics, VoL 21, Nos. 6/7, 1982 Simulating Physics with Computers Richard P. Feynman Department of Physics, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California 91107 Received May 7, 1981 1. INTRODUCTION On the program it says this is a keynote speech--and I don't know what a keynote speech is. I do not intend in any way to suggest what should be in this meeting as a keynote of the subjects or anything like that. I have my own things to say and to talk about and there's no implication that anybody needs to talk about the same thing or anything like it. So what I want to talk about is what Mike Dertouzos suggested that nobody would talk about. I want to talk about the problem of simulating physics with computers and I mean that in a specific way which I am going to explain. The reason for doing this is something that I learned about from Ed Fredkin, and my entire interest in the subject has been inspired by him. It has to do with learning something about the possibilities of computers, and also something about possibilities in physics. If we suppose that we know all the physical laws perfectly, of course we don't have to pay any attention to computers. It's interesting anyway to entertain oneself with the idea that we've got something to learn about physical laws; and if I take a relaxed view here (after all I'm here and not at home) I'll admit that we don't understand everything. -

Annual Report 2013.Pdf

ATOMIC HERITAGE FOUNDATION Preserving & Interpreting Manhattan Project History & Legacy preserving history ANNUAL REPORT 2013 WHY WE SHOULD PRESERVE THE MANHATTAN PROJECT “The factories and bombs that Manhattan Project scientists, engineers, and workers built were physical objects that depended for their operation on physics, chemistry, metallurgy, and other nat- ural sciences, but their social reality - their meaning, if you will - was human, social, political....We preserve what we value of the physical past because it specifically embodies our social past....When we lose parts of our physical past, we lose parts of our common social past as well.” “The new knowledge of nuclear energy has undoubtedly limited national sovereignty and scaled down the destructiveness of war. If that’s not a good enough reason to work for and contribute to the Manhattan Project’s historic preservation, what would be? It’s certainly good enough for me.” ~Richard Rhodes, “Why We Should Preserve the Manhattan Project,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May/June 2006 Photographs clockwise from top: J. Robert Oppenheimer, General Leslie R. Groves pinning an award on Enrico Fermi, Leona Woods Marshall, the Alpha Racetrack at the Y-12 Plant, and the Bethe House on Bathtub Row. Front cover: A Bruggeman Ranch property. Back cover: Bronze statues by Susanne Vertel of J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves at Los Alamos. Table of Contents BOARD MEMBERS & ADVISORY COMMITTEE........3 Cindy Kelly, Dorothy and Clay Per- Letter from the President..........................................4 -

A Selected Bibliography of Publications By, and About, J

A Selected Bibliography of Publications by, and about, J. Robert Oppenheimer Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 17 March 2021 Version 1.47 Title word cross-reference $1 [Duf46]. $12.95 [Edg91]. $13.50 [Tho03]. $14.00 [Hug07]. $15.95 [Hen81]. $16.00 [RS06]. $16.95 [RS06]. $17.50 [Hen81]. $2.50 [Opp28g]. $20.00 [Hen81, Jor80]. $24.95 [Fra01]. $25.00 [Ger06]. $26.95 [Wol05]. $27.95 [Ger06]. $29.95 [Goo09]. $30.00 [Kev03, Kle07]. $32.50 [Edg91]. $35 [Wol05]. $35.00 [Bed06]. $37.50 [Hug09, Pol07, Dys13]. $39.50 [Edg91]. $39.95 [Bad95]. $8.95 [Edg91]. α [Opp27a, Rut27]. γ [LO34]. -particles [Opp27a]. -rays [Rut27]. -Teilchen [Opp27a]. 0-226-79845-3 [Guy07, Hug09]. 0-8014-8661-0 [Tho03]. 0-8047-1713-3 [Edg91]. 0-8047-1714-1 [Edg91]. 0-8047-1721-4 [Edg91]. 0-8047-1722-2 [Edg91]. 0-9672617-3-2 [Bro06, Hug07]. 1 [Opp57f]. 109 [Con05, Mur05, Nas07, Sap05a, Wol05, Kru07]. 112 [FW07]. 1 2 14.99/$25.00 [Ber04a]. 16 [GHK+96]. 1890-1960 [McG02]. 1911 [Meh75]. 1945 [GHK+96, Gow81, Haw61, Bad95, Gol95a, Hew66, She82, HBP94]. 1945-47 [Hew66]. 1950 [Ano50]. 1954 [Ano01b, GM54, SZC54]. 1960s [Sch08a]. 1963 [Kuh63]. 1967 [Bet67a, Bet97, Pun67, RB67]. 1976 [Sag79a, Sag79b]. 1981 [Ano81]. 20 [Goe88]. 2005 [Dre07]. 20th [Opp65a, Anoxx, Kai02]. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

ROBERT SERBER March 14, 1909–June 1, 1997

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ROBE R T S E R BE R 1 9 0 9 — 1 9 9 7 A Biographical Memoir by ROBE R T P . Cr E A S E Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2008 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives ROBERT SERBER March 14, 1909–June 1, 1997 BY ROBE RT P . CREASE OBERT SERBER (elected to the NAS in 1952) was one of Rthe leading theorists during the golden age of U.S. physics. He entered graduate school in 190 before such key discoveries as the neutron, positron, and deuteron and prior to the development of the principal tool of nuclear and high-energy physics, the particle accelerator. He retired from the Columbia University Physics Department (as its chairman) in 1978 after completion of the standard model of elementary particle physics, which comprises almost all known particles and forces in a single package, and which has proven hard to surpass. Shy and unostentatious, Serber did not mind being the detached spectator, and did not care when he was occasionally out of step with the mainstream, whether in politics or phys- ics. Nevertheless, others regularly counted on him for advice: he was an insider among insiders. He seemed to carry the entire field of physics in his head, and his particular strength was a synthetic ability. He could integrate all that was known of an area of physics and articulate it back to others clearly and consistently, explaining the connection of each part to the rest. -

Estrelas, Ci^Encia E a Bomba: Uma Entrevista Com Hans Bethe

o . Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Fsica, vol. 18, n 3, setembro, 1996 143 Estrelas, Ci^encia e a Bomba: Uma Entrevista com Hans Bethe Renato Ejnisman Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Rochester, Rochester NY 14627 USA Trabalho recebido em 12 de julho de 1996 Hans Bethe fala de trechos de sua vida como fsico, sobre a fabricac~ao da b omba at^omica, desarmamento e a situac~ao atual da ci^encia. Abstract Hans Bethe talks ab out pieces of his life as a physicist, ab out the making of the atomic bomb, disarmament and the current status of science. sido convidado p elo editor. Alem disso, a entrevista Hans Bethe faz parte de um grup o restrito de fsicos publicada na Folha foi traduzida, o que a faz menos que caram para a Historia. O curioso, no caso de precisa, e leve, em alguns casos, a ordem das p erguntas Bethe, e que, ap esar de seus 90 anos, completados em invertida p or quest~oes editoriais. julho de 1996, ele ainda faz Historia. Atualmente, ele e Antes de continuar, vale descrever um p ouco como um dos lderes em estudos sobre o mecanismo de explo- foi a entrevista. Eu cheguei na sala de Hans Bethe na s~ao em sup ernovas, tendo comecado a trabalhar nesta Universidade de Cornell em Ithaca (EUA) numa terca- area cerca de vinte anos atras, numa idade em que a feira a tarde (21/05/96) e quei surpreso em v^e-lo rme maioria dos fsicos se ap osenta. -

A Secrecy Primer

A Secrecy Primer As more countries acquire the scientific knowledge to build nuclear weapons, the U.S. response should not be heightened secrecy but a renewed commitment to strengthening political safeguards. David Hafemeister Secrecy is in the air. Last July, the Los Alamos National Laboratory, still recovering from the Wen Ho Lee “Chinese espionage” controversy, shut down classified work for 10 weeks after two computer disks containing sensitive material were reported missing. Some 12,000 personnel remained idle during a lengthy investigation that in the end revealed the two computer disks hadn't even existed–bar codes for the disks had been created and inventoried, but never used. Alternatively, anyone with a credit card and a casual interest in the secrets of bomb-making could have visited Amazon.com and purchased for $34.95 (plus shipping) The Los Alamos Primer: The First Lectures on How to Build an Atomic Bomb. The curious history of the Los Alamos Primer–a history in which I played a very small part–in itself offers a worthwhile primer on the evolving nature of secrecy in the nuclear age and on the need to develop political instruments to cope with the inevitable dissemination of knowledge and technology. In April 1943, Robert Serber, a protegé of J. Robert Oppenheimer, gave a series of five lectures on atomic physics to the new hires at Los Alamos. “The object,” declared the young physicist, “is to produce a practical military weapon in the form of a bomb in which the energy is released by a fast neutrino chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission.” Topics ranged from fast neutron reactions to the probability of predetonation. -

Trinity Site July 16, 1945

Trinity Site July 16, 1945 "The effects could well be called unprecedented, magnificent, beauti ful, stupendous, and terrifying. No man-made phenomenon of such tremendous power had ever occurred before. The lighting effects beggared description. The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun." Brig. Gen. Thomas Farrell A national historic landmark on White Sands Missile Range -- www.wsmr.army.mil Radiation Basics Radiation comes from the nucJeus of the gamma ray. This is a type of electromag individual atoms. Simple atoms like oxygen netic radiation like visible light, radio waves are very stable. Its nucleus has eight protons and X-rays. They travel at the speed of light. and eight neutrons and holds together well. It takes at least an inch of lead or eight The nucJeus of a complex atom like inches of concrete to stop them. uranium is not as stable. Uranium has 92 Finally, neutrons are also emitted by protons and 146 neutrons in its core. These some radioactive substances. Neutrons are unstable atoms tend to break down into very penetrating but are not as common in more stable, simpler forms. When this nature. Neutrons have the capability of happens the atom emits subatomic particles striking the nucleus of another atom and and gamma rays. This is where the word changing a stable atom into an unstable, and "radiation" comes from -- the atom radiates therefore, radioactive one. Neutrons emitted particles and rays. in nuc!ear reactors are contained in the Health physicists are concerned with reactor vessel or shielding and cause the four emissions from the nucleus of these vessel walls to become radioactive. -

The Role of Tactical Nuclear Weapons in American China Policy: 1950-1963

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2016 The Role of Tactical Nuclear Weapons in American China Policy: 1950-1963 James Poppino University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Poppino, James, "The Role of Tactical Nuclear Weapons in American China Policy: 1950-1963" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4910. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4910 THE ROLE OF TACTICAL NUCLEAR WEAPONS IN AMERICAN CHINA POLICY: 1950- 1963 by JAMES D. POPPINO B.A. University of Central Florida, 1995 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2016 Major Professor: Hong Zhang © 2016 James Poppino ii ABSTRACT This study demonstrates that tactical nuclear weapons occupied a central and essential role in US military policy for confronting the Peoples Republic of China between 1950 and 1963. Historians seldom look at tactical nuclear weapons as a separate and distinct component of American foreign policy and generally place these weapons as a subset of a strategic doctrine directed at the Soviet Union. -

Revisiting the Los Alamos Primer B

Revisiting The Los Alamos Primer B. Cameron Reed Citation: Physics Today 70, 9, 42 (2017); View online: https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.3692 View Table of Contents: http://physicstoday.scitation.org/toc/pto/70/9 Published by the American Institute of Physics Articles you may be interested in In the digital age, physics students and professors prefer paper textbooks Physics Today 70, 30 (2017); 10.1063/PT.3.3657 Clippers, yachts, and the false promise of the wave line Physics Today 70, 52 (2017); 10.1063/PT.3.3627 Interplanetary sand traps Physics Today 70, 78 (2017); 10.1063/PT.3.3672 The new Moon Physics Today 70, 38 (2017); 10.1063/PT.3.3593 Mobilizing US physics in World War I Physics Today 70, 44 (2017); 10.1063/PT.3.3660 A thermodynamic theory of granular material endures Physics Today 70, 20 (2017); 10.1063/PT.3.3682 Cameron Reed is a professor of physics at Alma College in Michigan. REVISITING B. Cameron Reed A concise packet of lecture notes offers a window into one of the turning points of 20th-century history. n April 1943, scientists began gathering at a top-secret new laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, to design and build the world’s first atomic bombs. Most of them had been involved in nuclear fission research, but due to secrecy restrictions, few had any sense of the immensity of the project they were about to undertake. Their goal was to leverage the phenomenon of nuclear fission, discovered only four years earlier, to produce nuclear weapons in time to affect World War II. -

Character List

Character List - Bomb Use this chart to help you keep track of the hundreds of names of physicists, freedom fighters, government officials, and others involved in the making of the atomic bomb. Scientists Political/Military Leaders Spies Robert Oppenheimer - Winston Churchill -- Prime Klaus Fuchs - physicist in designed atomic bomb. He was Minister of England Manhattan Project who gave accused of spying. secrets to Russia Franklin D. Roosevelt -- Albert Einstein - convinced President of the United States Harry Gold - spy and Courier U.S. government that they for Russia KGB. Narrator of the needed to research fission. Harry Truman -- President of story the United States Enrico Fermi - created first Ruth Werner - Russian spy chain reaction Joseph Stalin -- dictator of the Tell Hall -- physicist in Soviet Union Igor Korchatov -- Russian Manhattan Project who gave physicist in charge of designing Adolf Hitler -- dictator of secrets to Russia bomb Germany Haakon Chevalier - friend who Werner Reisenberg -- Leslie Groves -- Military approached Oppenheimer about German physicist in charge of leader of the Manhattan Project spying for Russia. He was designing bomb watched by the FBI, but he was not charged. Otto Hahn -- German physicist who discovered fission Other scientists involved in the Manhattan Project: Aage Niels Bohr George Kistiakowsky Joseph W. Kennedy Richard Feynman Arthur C. Wahl Frank Oppenheimer Joseph Rotblat Robert Bacher Arthur H. Compton Hans Bethe Karl T. Compton Robert Serber Charles Critchfield Harold Agnew Kenneth Bainbridge Robert Wilson Charles Thomas Harold Urey Leo James Rainwater Rudolf Pelerls Crawford Greenewalt Harold DeWolf Smyth Leo Szilard Samuel K. Allison Cyril S. Smith Herbert L. Anderson Luis Alvarez Samuel Goudsmit Edward Norris Isidor I. -

![J. Robert Oppenheimer Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3787/j-robert-oppenheimer-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-1283787.webp)

J. Robert Oppenheimer Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

J. Robert Oppenheimer Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2016 Revised 2016 June Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms998007 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm77035188 Prepared by Carolyn H. Sung and David Mathisen Revised and expanded by Michael Spangler and Stephen Urgola in 2000, and Michael Folkerts in 2016 Collection Summary Title: J. Robert Oppenheimer Papers Span Dates: 1799-1980 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1947-1967) ID No.: MSS35188 Creator: Oppenheimer, J. Robert, 1904-1967 Extent: 76,450 items ; 301 containers plus 2 classified ; 120.2 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Physicist and director of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey. Correspondence, memoranda, speeches, lectures, writings, desk books, lectures, statements, scientific notes, and photographs chiefly comprising Oppenheimer's personal papers while director of the Institute for Advanced Study but reflecting only incidentally his administrative work there. Topics include theoretical physics, development of the atomic bomb, the relationship between government and science, nuclear energy, security, and national loyalty. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Bethe, Hans A. (Hans Albrecht), 1906-2005--Correspondence. Birge, Raymond T. (Raymond Thayer), 1887- --Correspondence.