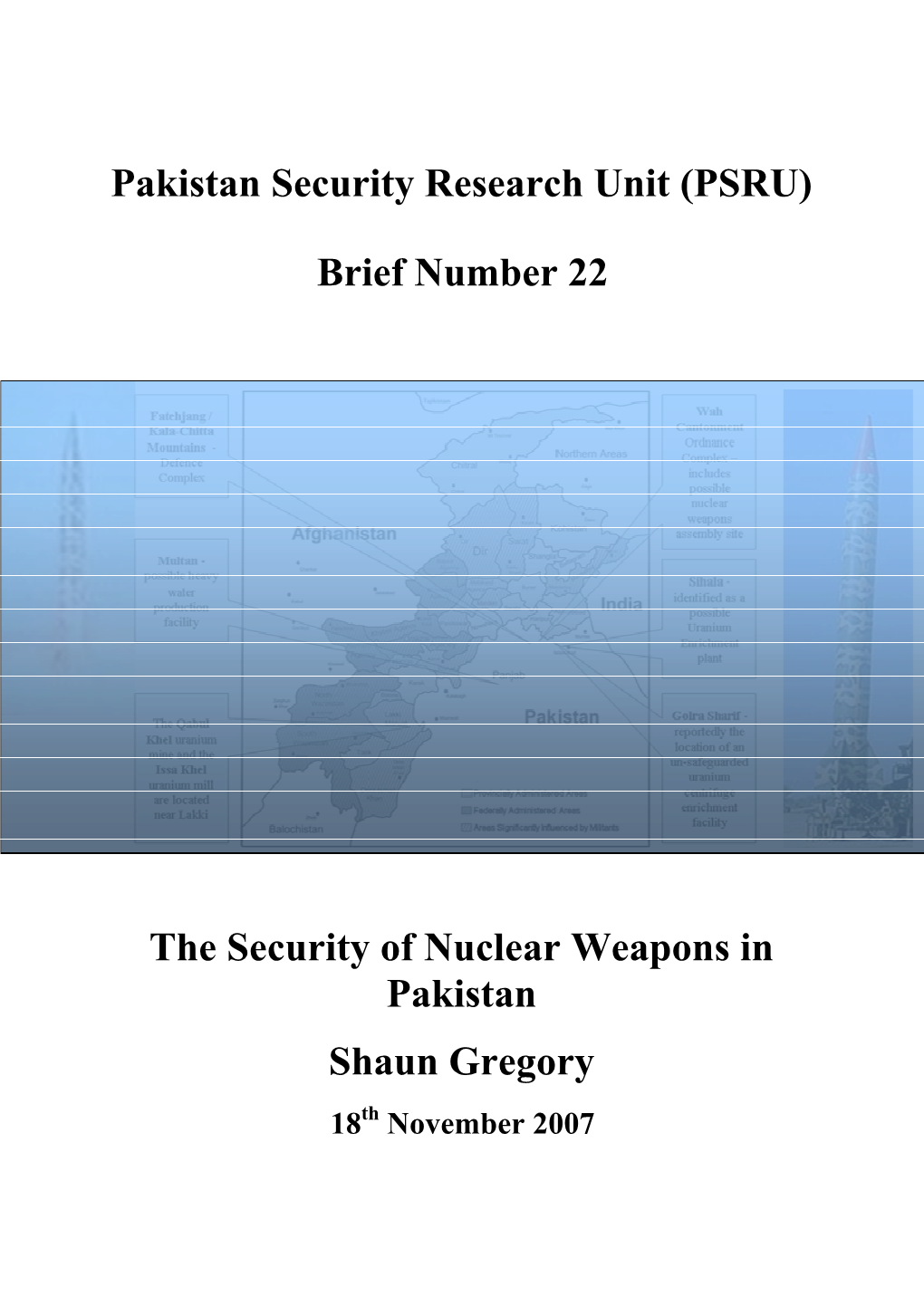

The Security of Nuclear Weapons in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan's Quest for Security of Nuclear Weapons: an Analysis

Pakistan Social Sciences Review P-ISSN 2664-0422 December 2018, Vol. 2, No. 2 [155-172] O-ISSN 2664-0430 RESEARCH PAPER Pakistan’s Quest for Security of Nuclear Weapons: An Analysis Muhammad Jawad Hashmi 1 Ashfaq Ahmed 2 Muhammad Owais 3 1. Lecturer at the Dept of Political Science & International Relations, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Punjab, Pakistan. 2. Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science and International Relations University of Sargodha, Punjab, Pakistan 3. Assistant Professor, Department of political science and international Relations, SSSH, Library building, 4th floor, UMT, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan PAPER INFO ABSTRACT Received: Fall of Dhaka in 1971 and Indian Nuclear Explosions in 1974, August 16, 2018 changed the course of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program. Accepted: Pakistan developed nuclear weapons due to Indian December 24, 2018 conventional and strategic superiority. The objective of this Online: study is to highlight Pakistan’s efforts to secure its nuclear December 30, 2018 program. It emphasizes that Pakistan’s nuclear weapons are Keywords: heavily guarded and secure. This paper is descriptive in nature Nuclear weapon, and completed in the light of qualitative research method. Paper Weapon of Most concludes that though Pakistan nuclear authorities have Destructions implemented personnel reliability program. It implements (WMDs), international safeguards yet international community is raising questions on security mechanism and safety of Pakistan’s Security nuclear weapons. The most important diplomatic task in front Corresponding of Pakistan at this time is to fight against misunderstandings Author: perceived by international community and to provide danalyst@hotma satisfaction to the world. il.com Introduction Since, Pakistan became the nuclear power, it remained under stressful scenario. -

Annexures for Annual Report 2020

List of Annexures Annex A Minutes of the Annual General Meeting held on March 08, 2019 Annex B Detailed Expenditures on Purchase and Establishment of PCATP Head Office Islamabad Annex C Policy guidelines for Online Teaching-Learning and Assessment Implementation Annex D Thesis guidelines for graduating batch during COVID-19 pandemic Annex E Inclusion of PCATP in NAPDHA Annex F Inclusion of role of Architects and Town Planners in the CIDB Bill 2020 Annex G Circulation List for Compliance of PCATP Ordinance IX of 1983 Annex H Status of Institutions Offering Architecture and Town Planning Undergraduate Degree Programs in Pakistan Annex I List of Registered Members and Firms who have contributed towards COVID- 19 fund in PCATP Account Annex J List of Registered Members and Firms who have contributed towards COVID- 19 fund in IAP Account Audited Accounts and Balance Sheet of PCATP General Fund and RHS Annex K Account for the Year 2018-2019 Page | 1 ANNEX A MINUTES OF THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE PAKISTAN COUNCIL OF ARCHITECTS AND TOWN PLANNERS ON FRIDAY, 8th MARCH, 2019, AT RAMADA CREEK HOTEL, KARACHI. In accordance with the notice, the Annual General Meeting of the Pakistan Council of Architects and Town Planners was held at 1700 hrs on Friday, 8th March, 2019 at Crystal Hall, Ramada Creek Hotel, Karachi, under the Chairmanship of Ar. Asad I. A. Khan. 1.0 AGENDA ITEM NO.1 RECITATION FROM THE HOLY QURAN 1.1 The meeting started with the recitation of Holy Quran, followed by playing of National Anthem. 1.2 Ar. FarhatUllahQureshi proposed that the house should offer Fateha for PCATP members who have left us for their heavenly abode. -

'Nuclear Learning in Pakistan Since 1998'

‘Nuclear Learning in Pakistan since 1998’ Naeem Ahmad Salik (20881392) B.A., Pakistan Military Academy, 1974; M.A. (History), University of the Punjab, 1981; B.Sc. Hons. (War Studies), Balochistan University, 1985; M.Sc. (International Politics and Strategic Studies), University of Wales, Aberystwyth, 1990. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences Political Science and International Relations and the Centre for Muslim States and Societies (CMSS) 2015 Abstract Nuclear learning is a process through which states that acquire nuclear weapons capability learn to manage it through the development of nuclear doctrines, command and control structures, safety and security mechanisms, regulatory regimes and acquire an understanding of both the technological characteristics of these weapons as well as their politico-strategic ramifications. This enables them to achieve a stable strategic balance through a sagacious application of these formidable instruments of power. Pakistan’s nuclear programme has always been beset with controversies and viewed with concern by the international community. These concerns have been accentuated by the spill over of the war in Afghanistan and the widespread incidence of terrorism and extremism within the country itself. In the pre-1998 period Pakistan had adopted a policy of ambiguity and denial of a nuclear weapons programme which combined with the secrecy surrounding the programme had stifled any discussion of issues related to management of an operational nuclear capability and it only started coming to grips with these issues after the May 1998 nuclear tests. This study about Pakistan’s learning experience in managing its nuclear capability suggests that a state that is perpetually afflicted by political instability and weak institutional structures could effectively handle its nuclear arsenal like a normal nuclear state provided it expends requisite effort and resources towards this end. -

Multivariate Analysis for the Assessment of Herbaceous Roadsides Vegetation of Wah Cantonment

Bashir et al., The Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, 26(2): 2016, Page:J.457 Anim.-464 Plant Sci. 26(2):2016 ISSN: 1018-7081 MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF HERBACEOUS ROADSIDES VEGETATION OF WAH CANTONMENT H. Bashir, S. S. Ahmad*, A. Jabeen and S. Erum Department of Environmental Sciences, Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. *Corresponding Author’s email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The present research was conducted along the roadside of Wah Cantonment to determine the associations and relationships between the plant communities and soil, grouping and quantification of plant communities using multivariate ordination techniques. Braun-Blanquet technique was applied for herbaceous data collection and quadrats of 1 1 square meter were laid. The whole floristic data were collected from 50 different sites through random sampling and cover values for plants were predicted through visual estimation.A whole of 36 species belonging to 18 different families were indentified. The ordination techniques of TWINSPAN (Two Way Indicator Species Analysis) and DCA (Detrended Correspondence Analysis) were carried out to classify the data. TWINSPANdivided the whole data into four groups with two major groups having communities of Vicia-Verbena, Convolvulus-Parthenium, Cynodon-Rumex and Euphorbia- Lepidium while minor groups had communities of Cannabis-Dicliptera and Coronopus-Sisymbrium. DCAwas used to classify the data and it identified the cluster of species in ordinate space, divided the data in four groups, and verified the results obtained from TWINSPAN. Cynodondactylon and Cannabis sativa were emerged as the most dominant and second dominant species after DCA.The present study will provide the baseline information about the roadside vegetation of Wah Cantonment and will be helpful for preserving and better management of the native flora. -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Defence Services Audit Year 2014-15

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DEFENCE SERVICES AUDIT YEAR 2014-15 AUDITOR-GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS iii PREFACE v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vi AUDIT STATISTICS CHAPTER-1 Ministry of Defence Production 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Status of Compliance of PAC Directives 1 AUDIT PARAS 1.3 Recoverable / Overpayments 3 1.4 Loss to State 26 1.5 Un-authorized Expenditure 29 1.6 Mis-procurement of Stores / Mis-management of contract 33 1.7 Non-Production of Records 45 CHAPTER-2 Ministry of Defence 2.1 Introduction48 2.2 Status of Compliance of PAC Directives 48 AUDIT PARAS Pakistan Army 2.3 Recoverable / Overpayments 50 2.4 Loss to State 63 2.5 Un-authorized Expenditure 67 2.6 Mis-procurement of Stores / Mis-management of Contract 84 i 2.7 Non-Production of Auditable Records 95 Military Lands and Cantonments 2.8 Recoverable / Overpayments 100 2.9 Loss to State 135 2.10 Un-authorized Expenditure 152 Pakistan Air Force 2.11 Recoverable / Overpayments 156 2.12 Loss to State 171 2.13 Un-authorized Expenditure 173 2.14 Mis-procurement of Stores / Mis-management of contract 181 Pakistan Navy 2.15 Recoverable / Overpayments 184 2.16 Loss to State 197 2.17 Un-authorized Expenditure 198 2.18 Mis-procurement of Stores / Mis-management of contract 207 Military Accountant General 2.19 Recoverable / Overpayments 215 2.20 Un-authorized Expenditure 219 Inter Services Organization (ISO’s) 2.21 Recoverable / Overpayments 222 Annexure-I MFDAC Paras (DGADS North) Annexure-II MFDAC Paras (DGADS South) ii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS -

Pof Catalogue

Force Behind the Forces Lt. Gen. Ali Amir Awan, HI(M) Chairman POF Board Message from the Chairman Pakistan Ordnance Factories is country’s premier defence production organization. We warmly welcome our international clients from friendly countries and offer a broad range of defence products manufactured on highest level of quality standards at most competitive prices. Established in 1951, POF is the largest state owned defence manufacturer in Pakistan. Besides being the main supplier of Pakistan Armed Forces and the law enforcement agencies, POF exports to a number of countries across the globe. Having a work force of over 27,000 skilled employees in 14 defence industrial units and a number of commercial subsidiary companies POF employees more than 20,000 plants scattered in the gigantic industrial complex located at Wah Cantonment in Pakistan. Our product range is exquisitely portrayed in this catalogue. We display it in most of the international defence exhibitions. POF’s Exports Division employees experts who take care of customer requirements in professional manner with utmost promptness. You may send all of your inquiries to us on [email protected] with my personal assurance of excellent assistance from POF. Disclaimer The technical values mentioned in the catalogue / website are average values which have been established in trials under customary conditions. We reserve the right to deviations within normal end-user practice. These specifications do not constitute a warranty and do not release the end-user from undertaking suitability tests under reigning ambient conditions. All the illustrations shown and offered are non-binding, in particular as regards design, size and color of the products. -

The Terrorist Threat to Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

JULY 2009 . VOL 2 . ISSUE 7 The Terrorist Threat tiers of armed forces personnel to guard operations occur. It operates a tightly nuclear weapons facilities, the use of controlled identification system to to Pakistan’s Nuclear physical barriers and intrusion detectors assure the identity of those involved in Weapons to secure nuclear weapons facilities, the the nuclear chain of command, and it also physical separation of warhead cores uses a rudimentary Permissive Action By Shaun Gregory from their detonation components, Link (PAL) type system to electronically and the storage of the components in lock its nuclear weapons. This system al-qa`ida has made numerous protected underground sites. uses technology similar to the banking statements about a desire to obtain industry’s “chip and pin” to ensure that nuclear weapons for use against the With respect to personnel reliability, even if weapons fall into terrorist hands United States and Western interests.1 the Pakistan Army conducts a tight they cannot be detonated.6 While many of these statements are selection process drawing almost rhetorical hyperbole, the scale of the exclusively on officers from Punjab Finally, Pakistan makes extensive use potential destructiveness of nuclear Province who are considered to have of secrecy and deception. Significant weapons, the instability and “nuclear fewer links with religious extremism or elements of Pakistan’s nuclear porosity” of the context in Pakistan, and with the Pashtun areas of Pakistan from weapons infrastructure are kept a the vulnerabilities within Pakistan’s which groups such as the Pakistani closely guarded secret. This includes nuclear safety and security arrangements Taliban mainly garner their support. -

PAKISTAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Pakistan Is a Federal Republic. With

PAKISTAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Pakistan is a federal republic. With the election of current president and head of state, Asif Ali Zardari, democratic rule was restored in 2008 after years of military government. Syed Yousuf Raza Gilani of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) served as prime minister and head of government. The PPP and its federal coalition partners controlled the executive and legislative branches of the national government and three of the four provincial assemblies. The military and intelligence services nominally reported to civilian authorities but essentially operated without effective civilian oversight. Generally, the police force reported to civilian authority, although there were instances in which it acted independently. The most serious human rights problems were extrajudicial killings, torture, and disappearances committed by security forces, as well as by militant, terrorist, and extremist groups, which affected thousands of citizens in nearly all areas of the country. Two prominent political figures, Punjab governor Salman Taseer and federal minister for minorities Shahbaz Bhatti, were assassinated due to their support for revisions of the blasphemy law and for Aasia Bibi, a Christian who had been sentenced to death under the law. Other human rights problems included poor prison conditions, instances of arbitrary detention, lengthy pretrial detention, a weak criminal justice system, insufficient training for prosecutors and criminal investigators, a lack of judicial independence in the lower courts, and infringements on citizens’ privacy rights. Harassment of journalists, some censorship, and self-censorship continued. There were some restrictions on freedom of assembly and some limits on freedom of movement. The number of religious freedom violations and discrimination against religious minorities increased, including some violations sanctioned by law. -

Pakistan: Violence Vs. Stability

PAKISTAN: VIOLENCE VS. STABILITY A National Net Assessment Varun Vira and Anthony H. Cordesman Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Working Draft: 5 May 2011 Please send comments and suggested revisions and additions to [email protected] Vira & Cordesman: Pakistan: Violence & Stability 3/5/11 ii Executive Summary As the events surrounding the death of Osama Bin Laden make all too clear, Pakistan is passing through one of the most dangerous periods of instability in its history. This instability goes far beyond Al Qa‟ida, the Taliban, and the war in Afghanistan. A net assessment of the patterns of violence and stability indicate that Pakistan is approaching a perfect storm of threats, including rising extremism, a failing economy, chronic underdevelopment, and an intensifying war, resulting in unprecedented political, economic and social turmoil. The Burke Chair at CSIS has developed an working draft of a net assessment that addresses each of these threats and areas of internal violence in depth, and does so within in the broader context of the religious, ideological, ethnic, sectarian, and tribal causes at work; along with Pakistan‟s problems in ideology, politics, governance, economics and demographics. The net assessment shows that these broad patterns of violence in Pakistan have serious implications for Pakistan‟s future, for regional stability, and for core US interests. Pakistan remains a central node in global counterterrorism. Osama Bin Laden was killed deep inside Pakistan in an area that raises deep suspicion about what Pakistani intelligence, senior military officers and government officials did and did not know about his presence – and the presence of other major terrorists and extremist like Sheik Mullah Omar and the “Quetta Shura Taliban.” Pakistan pursues its own agenda in Afghanistan in ways that provide the equivalent of cross- border sanctuary for Taliban and Haqqani militants, and that prolong the fighting and cause serious US, ISAF, and Afghan casualties. -

July, 2019 Regarding Grant of Loan for Rs.77,500/- to MEO Abbottabad on Account of Federation of Pakistan Vs

PROCEEDING OF THE CANTONMENT BOARD’s ORDINARY MEETING HELD ON 30-07-2019 IN THE OFFICE OF THE CANTONMENT BOARD WAH P R E S E N T 1. Brig. Khurram Shahzad, Station Commander, POFs Wah Cantt. --- President 2. Maj. Asad Zia, SSO, Station HQ, Wah --- Nominated Member 3. Mst. Uzma Khalid --- Nominated Member 4. Haji Amjad Mehmood Kashmiri --- Elected Member Ward No.1 5. Malik Misri Khan --- Elected Member Ward No.2 6. Raja Muhammad Ayub --- Elected Member Ward No.3 7. Mr.Muhmmad Imran --- Elected Member Ward No.4 8. Malik Azhar Nawaz --- Elected Member Ward No.5 9. Mr. Abdur Rehman --- Elected Member Ward No.7 10. Malik Fahad Mashood --- Elected Member Ward No. 8 11. Malik Ihtesham Iqbal --- Elected Member Ward No. 9 12. Ch.Mazhar Mehmood --- Elected Member Ward No.10 13. Mr. Javed Akhtar --- Member Minority Baber Hussain --- Secretary INDEX Item Description Page # ACCOUNT BRANCH 1 Monthly Statementof Accounts 2 Reimbursement of Medical Charges to Cantt Board Staff 3 Grant of Loan to MEO Hazara CircleAbbottabad Request for Transfer of Rs. 20.000 Million Cantt Fund Account No.4034820192 to 4 Pension Fund Account No.3034663881. 5 Re-appropriation of Funds (Major to Major Head) 6 Re-appropriation of Funds (Minor To Minor Head) 7 Temporary Appointment of Security Guards for Cantt Public Schools & Colleges 8 Temporary Appointment of 2 X Medical Officers 9 Appointment of Faculty for Cantt Public Schools & Colleges SANITATION BRANCH 10 Temporary appointment of 12 X Anti Dengue Workers 11 Temporary Appointment OF 20 X Sanitary Worker 12 Hiring of 20 x Labours (Daily Wages) for Monsoon Season GARDEN BRANCH 13 Supply of Trees for Monsoon Tree Plantation 14 Supply of Trees for Tree plantation Compaign 1st to 14th August 2019 15 Supply for Beautification of Ordnance Chowk 16 Supply of Rough Cutter for removing of Wild Growth 17 Supply of Lawn Mower REVENUE BRANCH Auction of Collection Rights of Cattle Mandi Fee near Malakand Hotel G.T. -

België En De Bomluc Barbé De Rol Van België in De Proliferatie Van Kernwapens

België en de bomLuc Barbé De rol van België in de proliferatie van kernwapens 3 Inhoudsopgave Inleiding 7 DEEL 1: DE FEITEN 11 1. Van Belgisch Congo over Olen naar Hiroshima 13 1. Een erts met gigantische mogelijkheden 13 2. “Onze Kongo” 14 3. De Tweede Wereldoorlog 15 4. Een akkoord dat stof doet opwaaien 17 5. Geheimhouding en de eerste leugen 19 6. De eerste atoombommen 20 7. Nucleair afval 21 8. Uranium voor de Britten en de Duitsers 21 9. Uranium naar andere oorden 23 10. Russische spionnen in ons land? 25 11. Een Belgisch kernwapenprogramma? 29 12. Het Congolese uranium, vaststellingen & besluiten. 31 2. Het non-proliferatieverdrag en het Internationaal Atoom Energie Agentschap 35 1. De droom van de generaal 35 2. De droom van de wetenschapper 37 3. Landen met kernwapens 40 4. Brandhaarden met kernwapens 42 5. De strijd tegen de nucleaire proliferatie versus het eigenbelang 43 4 3. Van Olen naar Dimona: Congolees uranium voor Israël 45 1. Een vergeten boek 45 2. Van Auschwitz naar Dimona 46 3. Van Olen naar Dimona 52 4. Enkele bedenkingen 55 5. Israëliërs in Mechelen, anno 1961 58 6. België & Israël: nabeschouwingen 59 4. Korte geschiedenis van de Belgische nucleaire sector 61 1. Een aantal vaststellingen 66 5. Pakistan 69 1. Inleiding 69 2. De Pakistaanse nucleaire sector, van de onafhankelijkheid tot nu. 69 3. Vaststellingen & analyse 85 4. En België in dit alles? 94 5. Het “ALSTOM- Deleuze-dossier” 116 6. IRAK: Saddam en kernwapens 123 1. Ook Saddam wil de bom 123 2. Van Puurs en Engis naar Irak 126 3.