Why Cells and Viruses Cannot Survive Without an ESCRT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Identification of Genetic Determinants of Methanol

Journal of Fungi Article The Identification of Genetic Determinants of Methanol Tolerance in Yeast Suggests Differences in Methanol and Ethanol Toxicity Mechanisms and Candidates for Improved Methanol Tolerance Engineering Marta N. Mota 1,2, Luís C. Martins 1,2 and Isabel Sá-Correia 1,2,* 1 iBB—Institute for Bioengineering and Biosciences, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, 1049-001 Lisbon, Portugal; [email protected] (M.N.M.); [email protected] (L.C.M.) 2 Department of Bioengineering, Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, 1049-001 Lisbon, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Methanol is a promising feedstock for metabolically competent yeast strains-based biore- fineries. However, methanol toxicity can limit the productivity of these bioprocesses. Therefore, the identification of genes whose expression is required for maximum methanol tolerance is important for mechanistic insights and rational genomic manipulation to obtain more robust methylotrophic yeast strains. The present chemogenomic analysis was performed with this objective based on the screening of the Euroscarf Saccharomyces cerevisiae haploid deletion mutant collection to search for susceptibility ◦ phenotypes in YPD medium supplemented with 8% (v/v) methanol, at 35 C, compared with an equivalent ethanol concentration (5.5% (v/v)). Around 400 methanol tolerance determinants were Citation: Mota, M.N.; Martins, L.C.; identified, 81 showing a marked phenotype. The clustering of the identified tolerance genes indicates Sá-Correia, I. The Identification of an enrichment of functional categories in the methanol dataset not enriched in the ethanol dataset, Genetic Determinants of Methanol Tolerance in Yeast Suggests such as chromatin remodeling, DNA repair and fatty acid biosynthesis. -

Analysis of Gene Expression Data for Gene Ontology

ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Robert Daniel Macholan May 2011 ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION Robert Daniel Macholan Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Zhong-Hui Duan Dr. Chien-Chung Chan _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Dr. Chien-Chung Chan Dr. Chand K. Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Yingcai Xiao Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT A tremendous increase in genomic data has encouraged biologists to turn to bioinformatics in order to assist in its interpretation and processing. One of the present challenges that need to be overcome in order to understand this data more completely is the development of a reliable method to accurately predict the function of a protein from its genomic information. This study focuses on developing an effective algorithm for protein function prediction. The algorithm is based on proteins that have similar expression patterns. The similarity of the expression data is determined using a novel measure, the slope matrix. The slope matrix introduces a normalized method for the comparison of expression levels throughout a proteome. The algorithm is tested using real microarray gene expression data. Their functions are characterized using gene ontology annotations. The results of the case study indicate the protein function prediction algorithm developed is comparable to the prediction algorithms that are based on the annotations of homologous proteins. -

PLATFORM ABSTRACTS Abstract Abstract Numbers Numbers Tuesday, November 6 41

American Society of Human Genetics 62nd Annual Meeting November 6–10, 2012 San Francisco, California PLATFORM ABSTRACTS Abstract Abstract Numbers Numbers Tuesday, November 6 41. Genes Underlying Neurological Disease Room 134 #196–#204 2. 4:30–6:30pm: Plenary Abstract 42. Cancer Genetics III: Common Presentations Hall D #1–#6 Variants Ballroom 104 #205–#213 43. Genetics of Craniofacial and Wednesday, November 7 Musculoskeletal Disorders Room 124 #214–#222 10:30am–12:45 pm: Concurrent Platform Session A (11–19): 44. Tools for Phenotype Analysis Room 132 #223–#231 11. Genetics of Autism Spectrum 45. Therapy of Genetic Disorders Room 130 #232–#240 Disorders Hall D #7–#15 46. Pharmacogenetics: From Discovery 12. New Methods for Big Data Ballroom 103 #16–#24 to Implementation Room 123 #241–#249 13. Cancer Genetics I: Rare Variants Room 135 #25–#33 14. Quantitation and Measurement of Friday, November 9 Regulatory Oversight by the Cell Room 134 #34–#42 8:00am–10:15am: Concurrent Platform Session D (47–55): 15. New Loci for Obesity, Diabetes, and 47. Structural and Regulatory Genomic Related Traits Ballroom 104 #43–#51 Variation Hall D #250–#258 16. Neuromuscular Disease and 48. Neuropsychiatric Disorders Ballroom 103 #259–#267 Deafness Room 124 #52–#60 49. Common Variants, Rare Variants, 17. Chromosomes and Disease Room 132 #61–#69 and Everything in-Between Room 135 #268–#276 18. Prenatal and Perinatal Genetics Room 130 #70–#78 50. Population Genetics Genome-Wide Room 134 #277–#285 19. Vascular and Congenital Heart 51. Endless Forms Most Beautiful: Disease Room 123 #79–#87 Variant Discovery in Genomic Data Ballroom 104 #286–#294 52. -

Table 2. Significant

Table 2. Significant (Q < 0.05 and |d | > 0.5) transcripts from the meta-analysis Gene Chr Mb Gene Name Affy ProbeSet cDNA_IDs d HAP/LAP d HAP/LAP d d IS Average d Ztest P values Q-value Symbol ID (study #5) 1 2 STS B2m 2 122 beta-2 microglobulin 1452428_a_at AI848245 1.75334941 4 3.2 4 3.2316485 1.07398E-09 5.69E-08 Man2b1 8 84.4 mannosidase 2, alpha B1 1416340_a_at H4049B01 3.75722111 3.87309653 2.1 1.6 2.84852656 5.32443E-07 1.58E-05 1110032A03Rik 9 50.9 RIKEN cDNA 1110032A03 gene 1417211_a_at H4035E05 4 1.66015788 4 1.7 2.82772795 2.94266E-05 0.000527 NA 9 48.5 --- 1456111_at 3.43701477 1.85785922 4 2 2.8237185 9.97969E-08 3.48E-06 Scn4b 9 45.3 Sodium channel, type IV, beta 1434008_at AI844796 3.79536664 1.63774235 3.3 2.3 2.75319499 1.48057E-08 6.21E-07 polypeptide Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RIKEN cDNA 2310040G17 gene 1417619_at 4 3.38875643 1.4 2 2.69163229 8.84279E-06 0.0001904 BC056474 15 12.1 Mus musculus cDNA clone 1424117_at H3030A06 3.95752801 2.42838452 1.9 2.2 2.62132809 1.3344E-08 5.66E-07 MGC:67360 IMAGE:6823629, complete cds NA 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1454696_at -3.46081884 -4 -1.3 -1.6 -2.6026947 8.58458E-05 0.0012617 beta 1 Gnb1 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1417432_a_at H3094D02 -3.13334396 -4 -1.6 -1.7 -2.5946297 1.04542E-05 0.0002202 beta 1 Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RAD23a homolog (S. -

ARCHAEAL EVOLUTION Evolutionary Insights from the Vikings

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS Nature Reviews Microbiology | Published online 16 Jan 2017; doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.198 ARCHAEAL EVOLUTION Evolutionary insights from the Vikings The emergence of the eukaryotic cell ASGARD — after the invisible the closest known homologue of during evolution gave rise to all com- ‘Gods of Asgard’ in Norse mythology. eukaryotic epsilon DNA polymerases primordial plex life forms on Earth, including The superphylum consists of the identified thus far. eukaryotic multicellular organisms such as ani- previously identified Lokiarchaeota Members of the ASGARD super- mals, plants and fungi. However, the and Thorarchaeota phyla, and the phylum were particularly enriched vesicular and origin of eukaryotes and their char- newly identified Odinarchaeota and for eukaryotic signature proteins trafficking acteristic structural complexity has Heimdallarchaeota phyla. Using that are involved in intracellular components remained a mystery. The most recent phylogenomics, they discovered trafficking and secretion. Several are derived insights into eukaryogenesis support a strong phylogenetic association proteins contained domain signatures the endosymbiotic theory, which between ASGARD lineages and of eukaryotic transport protein from our proposes that the first eukaryotic eukaryotes that placed the eukaryote particle (TRAPP) complexes, which archaeal cell arose from archaea through the lineage in close proximity to the are involved in transport from the ancestor acquisition of an alphaproteobacterial ASGARD superphylum. endoplasmic -

Ubiquitin-Dependent Sorting in Endocytosis

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on September 29, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Ubiquitin-Dependent Sorting in Endocytosis Robert C. Piper1, Ivan Dikic2, and Gergely L. Lukacs3 1Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 2Buchmann Institute for Molecular Life Sciences and Institute of Biochemistry II, Goethe University School of Medicine, D-60590 Frankfurt, Germany 3Department of Physiology, McGill University, Montre´al, Que´bec H3G 1Y6, Canada Correspondence: [email protected] When ubiquitin (Ub) is attached to membrane proteins on the plasma membrane, it directs them through a series of sorting steps that culminate in their delivery to the lumen of the lysosome where they undergo complete proteolysis. Ubiquitin is recognized by a series of complexes that operate at a number of vesicle transport steps. Ubiquitin serves as a sorting signal for internalization at the plasma membrane and is the major signal for incorporation into intraluminal vesicles of multivesicular late endosomes. The sorting machineries that catalyze these steps can bind Ub via a variety of Ub-binding domains. At the same time, many of these complexes are themselves ubiquitinated, thus providing a plethora of potential mechanisms to regulate their activity. Here we provide an overview of how membrane proteins are selected for ubiquitination and deubiquitination within the endocytic pathway and how that ubiquitin signal is interpreted by endocytic sorting machineries. HOW PROTEINS ARE SELECTED FOR distinctions concerning different types of ligas- UBIQUITINATION es, their specificity for forming particular poly- Ub chains, and even the kinds of residues in biquitin (Ub) is covalently attached to sub- substrate proteins that can be ubiquitin modi- Ustrate proteins by the concerted action of fied, have been blurred with the discovery of E2-conjugating enzymes and E3 ligases (Var- mixed poly-Ub chains, new enzymatic mecha- shavsky 2012). -

Genetic and Genomic Analysis of Hyperlipidemia, Obesity and Diabetes Using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/Jngj) F2 Mice

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Nutrition Publications and Other Works Nutrition 12-19-2010 Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P. Stewart Marshall University Hyoung Y. Kim University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Arnold M. Saxton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Jung H. Kim Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nutrpubs Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-713 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nutrition at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nutrition Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stewart et al. BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/11/713 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P Stewart1, Hyoung Yon Kim2, Arnold M Saxton3, Jung Han Kim1* Abstract Background: Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common form of diabetes in humans and is closely associated with dyslipidemia and obesity that magnifies the mortality and morbidity related to T2D. The genetic contribution to human T2D and related metabolic disorders is evident, and mostly follows polygenic inheritance. The TALLYHO/ JngJ (TH) mice are a polygenic model for T2D characterized by obesity, hyperinsulinemia, impaired glucose uptake and tolerance, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. -

Heat Stress-Dependent Association of Membrane Trafficking Proteins

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 24 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.670499 Heat Stress-Dependent Association of Membrane Trafficking Proteins With mRNPs Is Selective Heike Wolff 1, Marc Jakoby 2, Lisa Stephan 2, Eva Koebke 2 and Martin Hülskamp 2* 1 Cluster of Excellence on Plant Sciences (CEPLAS), Botanical Institute, Cologne University, Cologne, Germany, 2 Botanical Institute, Biocenter, Cologne University, Cologne, Germany The Arabidopsis AAA ATPase SKD1 is essential for ESCRT-dependent endosomal sorting by mediating the disassembly of the ESCRTIII complex in an ATP-dependent manner. In this study, we show that SKD1 localizes to messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes upon heat stress. Consistent with this, the interactome of SKD1 revealed differential interactions under normal and stress conditions and included membrane transport proteins as well as proteins associated with RNA metabolism. Localization studies with selected interactome proteins revealed that not only RNA associated proteins but also several ESCRTIII and membrane trafficking proteins were recruited to messenger ribonucleoprotein granules after heat stress. Keywords: SKD1, endosomal trafficking, RNA metabolism, membrane trafficking, ESCRT, heat stress, mRNP Edited by: Abidur Rahman, Iwate University, Japan INTRODUCTION Reviewed by: Xiaohong Zhuang, Ubiquitinylated membrane proteins are targeted for degradation in lysosomes by the multivesicular The Chinese University of Hong body (MVB) pathway. MVB sorting is governed by proteins of the endosomal complex required Kong, China Viktor Zarsky, for transport (ESCRT). Four complexes, ESCRT0, ESCRTI, ESCRTII, and ESCRTIII, assemble Charles University, Czechia sequentially on endosomes to mediate invagination and fission of the MVBs’ outer membrane *Correspondence: (Huotari and Helenius, 2011; Gao et al., 2017). This process leads to the formation of intraluminal Martin Hülskamp vesicles (ILVs), whose content is degraded after fusion of the MVB with the lysosome. -

Genetic, Structural and Clinical Analysis of Spastic Paraplegia 4

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.20.21259482; this version posted July 20, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY 4.0 International license . Genetic, structural and clinical analysis of spastic paraplegia 4 Parizad Varghaei1,2, MD, Mehrdad A Estiar2,3, MSc, Setareh Ashtiani4, MSc, Simon Veyron5, PhD, Kheireddin Mufti2,3, MSc, Etienne Leveille6, MD, Eric Yu2,3, BSc, Dan Spiegelman, MSc2, Marie-France Rioux7, MD, Grace Yoon8, MD, Mark Tarnopolsky9, MD, PhD, Kym M. Boycott10, MD, Nicolas Dupre11,12, MD, MSc, Oksana Suchowersky4,13, MD, Jean-François Trempe5,PhD, Guy A. Rouleau2,3,14, MD, PhD, Ziv Gan-Or2,3,14, MD, PhD 1. Division of Experimental Medicine, Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2. The Neuro (Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital), McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 3. Department of Human Genetics, McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada 4. Alberta Children’s Hospital, Medical Genetics, Calgary, Alberta, Canada 5. Department of Pharmacology & Therapeutics and Centre de Recherche en Biologie Structurale - FRQS, McGill University, Montréal, Canada 6. Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada 7. Department of Neurology, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Québec, Canada. 8. Divisions of Neurology and Clinical and Metabolic Genetics, Department of Paediatrics, University of Toronto, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 9. Department of Pediatrics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada 10. Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada 11. -

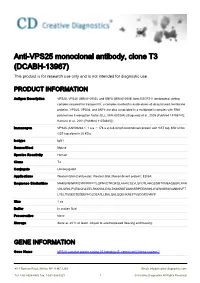

Anti-VPS25 Monoclonal Antibody, Clone T3 (DCABH-13967) This Product Is for Research Use Only and Is Not Intended for Diagnostic Use

Anti-VPS25 monoclonal antibody, clone T3 (DCABH-13967) This product is for research use only and is not intended for diagnostic use. PRODUCT INFORMATION Antigen Description VPS25, VPS36 (MIM 610903), and SNF8 (MIM 610904) form ESCRT-II (endosomal sorting complex required for transport II), a complex involved in endocytosis of ubiquitinated membrane proteins. VPS25, VPS36, and SNF8 are also associated in a multiprotein complex with RNA polymerase II elongation factor (ELL; MIM 600284) (Slagsvold et al., 2005 [PubMed 15755741]; Kamura et al., 2001 [PubMed 11278625]). Immunogen VPS25 (AAH06282.1, 1 a.a. ~ 176 a.a) full-length recombinant protein with GST tag. MW of the GST tag alone is 26 KDa. Isotype IgG1 Source/Host Mouse Species Reactivity Human Clone T3 Conjugate Unconjugated Applications Western Blot (Cell lysate); Western Blot (Recombinant protein); ELISA Sequence Similarities MAMSFEWPWQYRFPPFFTLQPNVDTRQKQLAAWCSLVLSFCRLHKQSSMTVMEAQESPLFNN VKLQRKLPVESIQIVLEELRKKGNLEWLDKSKSSFLIMWRRPEEWGKLIYQWVSRSGQNNSVFT LYELTNGEDTEDEEFHGLDEATLLRALQALQQEHKAEIITVSDGRGVKFF Size 1 ea Buffer In ascites fluid Preservative None Storage Store at -20°C or lower. Aliquot to avoid repeated freezing and thawing. GENE INFORMATION Gene Name VPS25 vacuolar protein sorting 25 homolog (S. cerevisiae) [ Homo sapiens ] 45-1 Ramsey Road, Shirley, NY 11967, USA Email: [email protected] Tel: 1-631-624-4882 Fax: 1-631-938-8221 1 © Creative Diagnostics All Rights Reserved Official Symbol VPS25 Synonyms VPS25; vacuolar protein sorting 25 homolog (S. cerevisiae); -

Endosome-Associated Complex, ESCRT-II, Recruits Transport Machinery for Protein Sorting at the Multivesicular Body

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Developmental Cell, Vol. 3, 283–289, August, 2002, Copyright 2002 by Cell Press Endosome-Associated Complex, ESCRT-II, Recruits Transport Machinery for Protein Sorting at the Multivesicular Body Markus Babst,2,4 David J. Katzmann,4 plays a critical role in the sorting of multiple cargo pro- William B. Snyder,2 Beverly Wendland,3 teins within the endosomal membrane system. and Scott D. Emr1 In a recent study, it has been demonstrated that sort- Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine and ing of the yeast hydrolase carboxypeptidase S (CPS) Howard Hughes Medical Institute into the MVB pathway requires monoubiquitination of School of Medicine the short cytoplasmic tail of the protein (Katzmann et University of California, San Diego al., 2001). Mutations in CPS that block this ubiquitin La Jolla, California 92093 modification result in mislocalization of the protein to the limiting membrane of the vacuole. Furthermore, a protein complex called ESCRT-I (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) binds to ubiquitinated Summary CPS and thereby directs sorting of the hydrolase into the MVB pathway (Katzmann et al., 2001). ESCRT-I is Sorting of ubiquitinated endosomal membrane pro- composed of three different protein subunits (Vps23, teins into the MVB pathway is executed by the class Vps28, and Vps37) which belong to the class E vacuolar E Vps protein complexes ESCRT-I, -II, and -III, and protein sorting (Vps) proteins, a group of 15 proteins the AAA-type ATPase Vps4. This study characterizes required for proper endosomal function, including the ف ESCRT-II, a soluble 155 kDa protein complex formed formation of MVBs (Odorizzi et al., 1998). -

Actin, Microtubule, Septin and ESCRT Filament Remodeling During Late Steps of Cytokinesis Cyril Addi, Jian Bai, Arnaud Echard

Actin, microtubule, septin and ESCRT filament remodeling during late steps of cytokinesis Cyril Addi, Jian Bai, Arnaud Echard To cite this version: Cyril Addi, Jian Bai, Arnaud Echard. Actin, microtubule, septin and ESCRT filament remodel- ing during late steps of cytokinesis. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, Elsevier, 2018, 50, pp.27-34. 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.01.007. hal-02114062 HAL Id: hal-02114062 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02114062 Submitted on 29 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License Actin, microtubule, septin and ESCRT filament remodeling during late steps of cytokinesis Cyril Addi1,2,3,#, Jian Bai1,2,3,# and Arnaud Echard1,2 1 Membrane Traffic and Cell Division Lab, Cell Biology and Infection department Institut Pasteur, 25–28 rue du Dr Roux, 75724 Paris cedex 15, France 2 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique CNRS UMR3691, 75015 Paris, France 3 Sorbonne Universités, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Paris 06, Institut de formation doctorale, 75252 Paris, France # equal contribution, alphabetical order correspondence: [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT Cytokinesis is the process by which a mother cell is physically cleaved into two daughter cells.