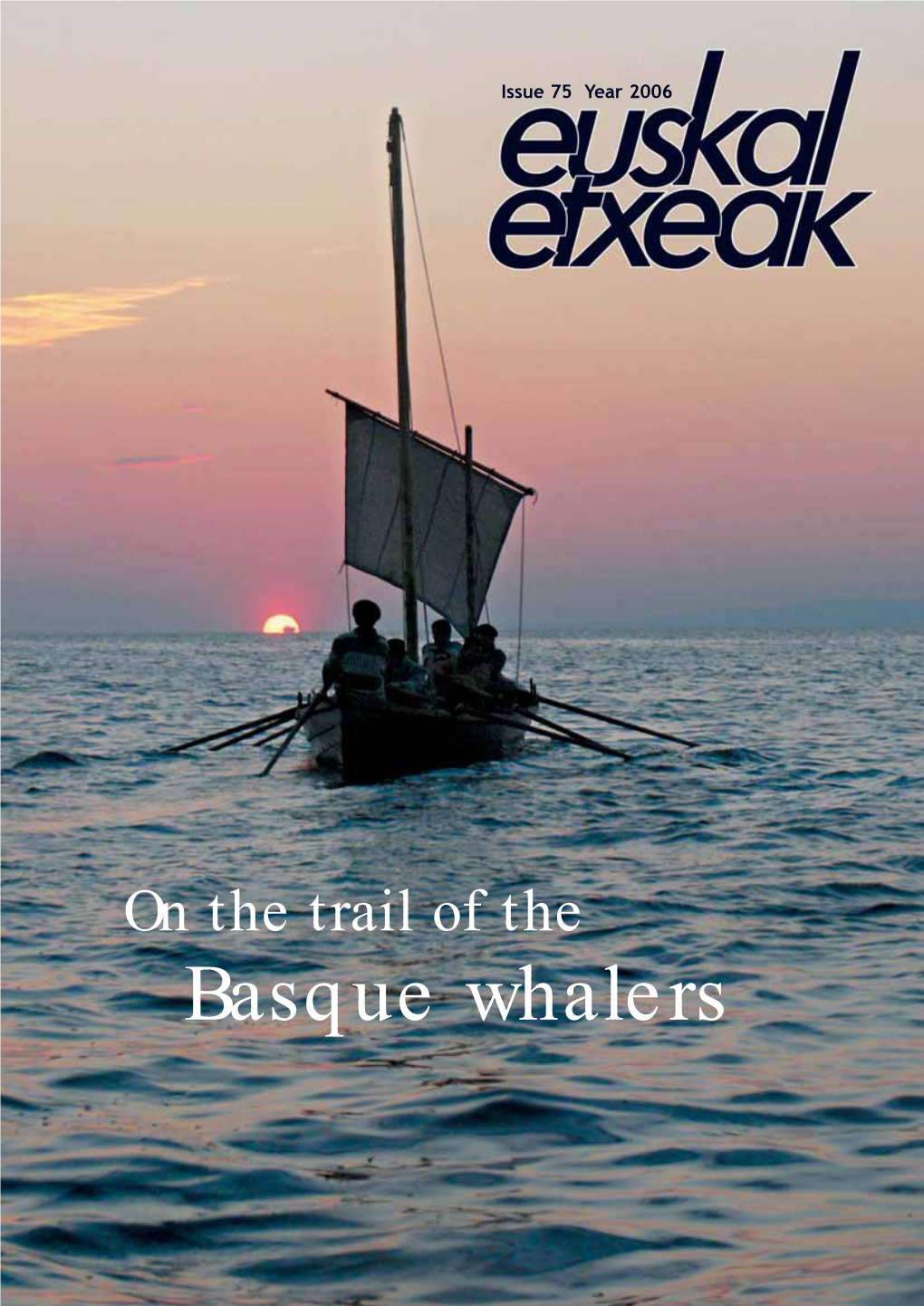

Basque Whalers AURKIBIDEA / TABLE of CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redress Movements in Canada

Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures -

Kings Lynn Hanse Regatta 2020 Saturday Entry Form V2

Kings Lynn Hanse Regatta 2020 Saturday 16th May 2019 Entry Form – Short Course sprints (Note: These 3 races will count towards the SECRF’s Nelson’s Cup; scoring based on the fastest boat for each club partaking) Name of Rowing or Sailing Club Name of Boat Class of Boat (e.g. Harker’s Yard Gig, St Ayles skiff) Colour(s) of Boat Contact Numbers (1) (in case of emergency) (2) Contact e-mail address Race Notes • A parental consent form will be required for any participants under the age of 16. All participant MUST wear a life jacket or buoyancy aid. • Races will be held in accordance with the Rules of Racing. A copy of which will be available and Coxes should ensure that they are familiar with, and abide by the rules. • Competitors participate in the event at their own risk and are responsible for their own safety and that of the boat at all times. We recommend that all boats have suitable current Public Liability Insurance (including racing cover) • Whilst safety boat cover will be provided all boats should carry a waterproofed means of communication. At a minimum this should be a fully charged mobile phone with contact numbers for race officials and preferably a working handheld VHF radio chM(37); nb; Kings Lynn Port operates on ch14 and will be on watch. • We ask all boats to display their allocated number at the start and finish of each race and a Racing Flag if at all possible, for the benefit of shore side spectators. Version: 01 Dec. -

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Bahía De Pasaia: Hacia Un Nuevo Puerto Urbano Bay of Pasajes

Ángel Martín Ramos Bahía de Pasaia: Bay of Pasajes: Hacia un nuevo puerto Towards a New Urban urbano Port Las influencias que ejerce la masa oceánica del Atlántico sobre el The effects that the Atlantic Ocean mass to Paris ran right up to the quayside.Work Norte de la Península Ibérica son moderadas a través del Mar have on the northern part of the Iberian began in 1870 on the port project Peninsula are moderated in the Bay of designed by the Engineer Francisco Lafar- Cantábrico en una transición llena de cualidades. Allí, sobre esa Biscay in a transition that is full of quali- ga, with the construction of the commer- costa, en el fondo del Golfo de Bizkaia se encuentra la Bahía de ties. Along this coastline lies the Bay of cial quays and the dredging of the sand- Pasaia, como una de los espectaculares accidentes geográficos Pasajes, a spectacular natural geograph- banks that were obstructing the bay and ical feature that facilitates the relation- which were exposed at low tide. The Port naturales que facilitan la relación entre mar y tierra en la Costa ship between the sea and land on the of Pasajes immediately showed exactly Vasca. Solamente a través de las ensenadas que forman las Basque Coast. The steeply sloping coast why the right choice of location had been desembocaduras de los ríos, con un despliegue de rías, bahías y of Guipuzcoa only manages to find an made and embarked on a process of opening to the sea through the creeks increasing its activity, decade after arenales, es como la abrupta costa guipuzcoana que se abre al that constitute the river estuaries, with a decade, as activities started to expand mar. -

Hondarribia Walking Tour Way of St

countrywalkers.com 800.234.6900 Spain: San Sebastian, Bilbao & Basque Country Flight + Tour Combo Itinerary Free-roaming horses wander the green pastures atop Mount Jaizkibel, where your walk brings panoramic views extending clear across Spain into southern France—from the Bay of Biscay to the Pyrenees. You’re on a walking tour in the Basque Country, a unique corner of Europe with its own ancient language and culture. You’ve just begun exploring this fascinating region—from Bilbao’s cutting-edge architecture to Hendaye’s beaches to the mountainous interior. Your week ahead also promises tasty glimpses of local culinary culture: a Basque cooking class, a festive dinner at a traditional gastronomic club, a homemade feast in a hillside farmhouse…. Speaking of food, isn’t it about time to begin your scenic seaward descent through the vineyards for lunch and wine tasting? On egin! (Bon appetit!) Highlights Join a private gastronomic club, or txoko, for an exclusive dinner as the members share their love of Basque cuisine. Live like royalty in a setting so beautiful it earned the honor of hosting Louis XIV and Maria Theresa’s wedding in St. Jean de Luz. Experience the vibrant nightlife in a Basque wine bar. Stroll the seaside paths that Spanish aristocracy once wandered in San Sebastián. Tour the world-famous Guggenheim Museum – one of the largest museums on Earth and an architectural phenomenon. Satisfy your cravings in a region with more Michelin-star rated restaurants than Paris. Rest your mind and body in a restored 17th-century palace, or jauregia. 1 / 10 countrywalkers.com 800.234.6900 Participate in a cooking demonstration of traditional Basque cuisine. -

Ruditapes Decussatus) Exploitation in the Plentzia Estuary (Basque Country, Northern Spain)

Modelling the management of clam (Ruditapes decussatus) exploitation in the Plentzia estuary (Basque Country, Northern Spain) Juan Bald & Angel Borja AZTI Foundation, Department of Oceanography and Marine Environment Herrera Kaia Portualdea z/g, 20110 PASAIA (Gipuzkoa) SPAIN Tel: +34 943 00 48 00 Fax: +34 943 00 48 01 www.azti.es [email protected] Abstract Some of the estuaries of the Basque Country (Northern Spain) have been areas of exploitation of clam populations, both by professional and illegal fishermen. There is a real possibility of overfishing and, therefore, the Department of Fisheries of the Basque Government needs to: (a) understand the situation relating to these populations; and (b) provide a tool to establish the most adequate management for the exploitation of clams. In order to simulate different alternatives for the exploitation, based upon scientific data on the population, the best tool available is a system dynamics model. Here the VENSIM® model was employed, utilising data on clam populations: summer stock and biomass in the Plentzia estuary, in 1998, 2000; winter stock in 1999, 2000, and 2001; the area occupied by the species; the length and weight class distribution; the number of fishermen; mean of biomass, captured by the fishermen; natural mortality, by length class; maturation; fertility rate; etc. This study improves previous experiences in modelling clam exploitation in the Plentzia and Mundaka estuaries. Following validation of the model, after running it for 1 and 10 years, some cases were simulated. This analysis was undertaken in order to establish the effect of modifying the number of fishermen, the aperture-close season of captures, the minimum sustainable biomass, the exploitation area and the minimum legal length for shellfishing. -

Zuberoako Herri Izendegia

92 ZUBEROAKO HERRI IZENDEGIA Erabilitako irizpideak Zergatik lan hau 1998an eskatu zitzaion Onomastika batzordeari Zuberoako herri izenak berraztertzea, zenbait udalek euskal izenak bide-seinaletan eta erabiltzeko asmoa agertu baitzuten eta euskaltzaleen artean ez izaki adostasunik izen horien gainean. Kasu batzuetan, izan ere, formak zaharkitu, desegoki edo egungo euskararen kontrakotzat jotzen ziren. Hori dela eta, zenbait herritan, Euskaltzaindiak Euskal Herriko udal izendegia-n (1979) proposatuari muzin eginik, bestelako izenak erabiltzen ari ziren. Bestalde, kontuan hartu behar da azken urteotan burutu lana, eta bereziki Nafarroako herri izendegia (1990) eta geroztik plazaratu “Nafarroako toponimia nagusiaren normalizaziorako irizpideak” Euskera, 1997, 3, 653-666. Guzti hori ezin zitekeen inola ere bazter. Onomastika batzordeak, Zuberoako euskaltzainen laguntza ezezik, hango euskaltzaleena ere (Sü Azia elkartearena, bereziki) eskatu zuen, iritziak hurbiletik ezagutzeko. Hiru bilkura egin ziren: Bilboko egoitzan lehendabizikoa, Iruñeko ordezkaritzan bigarrena eta Maulen hirugarrena. Proposamena Euskaltzaindiaren batzarrean aurkeztu eta 1998ko abenduan erabaki. Aipatu behar da, halaber, Eskiula sartu dugula zerrendan, nahiz herri hori Zuberoatik kanpo dagoen. Eztabaida puntuak eta erabilitako irizpideak Egungo euskara arautua eta leku-izenak Batzuek, hobe beharrez, euskara batuko hiztegi arrunterako onartu irizpide eta moldeak erabili nahi izan dituzte onomastika alorrean, leku-izenak zein bestelako izen bereziak, neurri batean, hizkuntza arruntaren sistematik kanpo daudela ikusi gabe. Toponimian, izan ere, bada maiz aski egungo hizkuntzari ez dagokion zerbait, aurreko egoeraren oihartzuna. Gainera, Euskaltzaindiak aspaldi errana du, Bergaran 1978an egin zuen biltzarraren ondoren, leku-- izenek trataera berezia dutela. Ikus, batez ere, kontsonante busti-palatalen grafiaz erabakia, Euskera 24:1, 1979, 91-92. Ñ letra hiztegi arruntean arras mugatua izan arren, leku-izenetan erabiltzen da: Oñati (G), Abadiño (B), Iruñea (N) eta Añana (A). -

Acadiens and Cajuns.Indb

canadiana oenipontana 9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord innsbruck university press SERIES canadiana oenipontana 9 iup • innsbruck university press © innsbruck university press, 2009 Universität Innsbruck, Vizerektorat für Forschung 1. Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Umschlag: Gregor Sailer Umschlagmotiv: Herménégilde Chiasson, “Evangeline Beach, an American Tragedy, peinture no. 3“ Satz: Palli & Palli OEG, Innsbruck Produktion: Fred Steiner, Rinn www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-902571-93-9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord Contents — Table des matières Introduction Avant-propos ....................................................................................................... 7 Ursula Mathis-Moser – Günter Bischof des matières Table — By Way of an Introduction En guise d’introduction ................................................................................... 23 Contents Herménégilde Chiasson Beatitudes – BéatitudeS ................................................................................................. 23 Maurice Basque, Université de Moncton Acadiens, Cadiens et Cajuns: identités communes ou distinctes? ............................ 27 History and Politics Histoire -

Farm-To-Family / Adv. in Basque Country 2014

BASQUE FAMILY BONDS Farm-to-Family Adventures in the Deep Heart of Basque Country 2014 Departures: July 27 and August 17 -- or as a private family departure any time Eight days exploring deep Basque Country, including: Bilbao, Ordizia, Mutriku, Zumaia, San Sebastian, Beizama and Bidegoian Trip Overview The first things that come to mind when asked to conjure up Basque Country may be the glittering Guggenheim or San Sebastian’s cult of culinary superstars. And while world class art & architecture and Michelin-starred restaurants are indeed fascinating features of this remarkable region, it’s the fierce independence of the region’s proud people, the dramatic diversity of its landscapes and the supreme importance placed on family, food and friends that leave their indelible mark on us. And through this lens of family-focused adventure, discovery and connection, we’ll enter deep into the heart of Basque culture. Whether milking sheep & making cheese on a small farm, navigating Bilbao from the perch of a paddleboard, hiking to a 17th C. farmstead for a home-hosted meal or gathered around the rustic wooden table of a cider house, we’ll experience Basque Country accompanied by local friends, exploring its natural grandeur and experiencing its most cherished family traditions. We’ve crafted this trip with families and their shared experience at its core. We’ve controlled the tempo, minimized travel times & hotel changes, built-in plenty of unstructured time and have even arranged for a parents’ night out. After all, at the heart of our Basque team are families that love to travel together, too – from my own, to our trip leader’s, to our favorite Basque ambassador and host, Pello, and his beautiful three generations of family that we’re fortunate enough to meet along the way. -

Condensation Water in Heritage Touristic Caves: Isotopic and Hydrochemical Data and a New Approach for Its Quantification Through Image Analysis

Received: 20 August 2020 Revised: 5 February 2021 Accepted: 5 February 2021 DOI: 10.1002/hyp.14083 RESEARCH ARTICLE Condensation water in heritage touristic caves: Isotopic and hydrochemical data and a new approach for its quantification through image analysis Cristina Liñán1,2 | José Benavente3 | Yolanda del Rosal1 | Iñaki Vadillo2 | Lucía Ojeda2 | Francisco Carrasco2 1Research Institute, Nerja Cave Foundation. Carretera de Maro, Malaga, Spain Abstract 2Centre of Hydrogeology of University of Condensation water is a major factor in the conservation of heritage caves. It can Malaga, Department of Geology, Faculty of cause dissolution of the rock substrate (and the pigments of rock art drawn on it) or Science, University of Malaga, Malaga, Spain 3Department of Geodynamics-Water Research covering thereof with mineral components, depending on the chemical saturation Institute, Faculty of Science, University of degree of the condensation water. In show caves, visitors act as a source of CO2 and Granada, Granada, Spain thus modify the microclimate, favouring negative processes that affect the conserva- Correspondence tion of the caves. In spite of their interest, studies of the chemical composition of this Cristina Liñán, Research Institute, Nerja Cave Foundation. Carretera de Maro s/n, 29787, type of water are scarce and not very detailed. In this work we present research on Nerja, Malaga, Spain. the condensation water in the Nerja Cave, one of the main heritage and tourist caves Email: [email protected] in Europe. The joint analysis of isotopic, hydrochemical, mineralogical and microbio- logical data and the use of image analysis have allowed us to advance in the knowl- edge of this risk factor for the conservation of heritage caves, and to demonstrate the usefulness of image analysis to quantify the scope of the possible corrosion con- densation process that the condensation water could be producing on the bedrock, speleothem and rock art. -

San Sebastián-Donostia Maribel’S Guide to San Sebastián ©

San Sebastián-Donostia Maribel’s Guide to San Sebastián © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ September 2019 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 3 • Vinoteca Bernardina Exploring Donostia On Your Own - Page 5 • Damadá Gastroteka Guided City Tours - Page 9 Dining in San Sebastián-Donostia The Michelin Stars - Page 34 Private City Tours - Page 10 • Akelaŕe Cooking Classes and Schools - Page 11 • Mugaritz San Sebastián’s Beaches - Page 12 • Restaurant Martín Berasategui • Restaurant Arzak Donostia’s Markets - Page 14 • Kokotxa Sociedad Gastronómica - Page 15 • Mirador de Ulia Performing Arts - Page 16 • Amelia • Zuberoa My Shopping Guide - Page 17 • Restaurant Alameda Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” - Page 18 Creative and Contemporary Cuisine - Page 35 Our Favorite Stops In The Parte Vieja - Page 20 • Biarritz Bar and Restaurant • Restaurante Ganbara • Casa Urola • Casa Vergara • Bodegón Alejandro • A Fuego Negro • Bokado Mikel Santamaria • Gandarias • Eme Be Garrote • La Cuchara de San Telmo • Agorregi • Bar La Cepa • Rekondo • La Viña • Galerna Jan Edan • Bar Tamboril • Zelai Txiki • Bar Txepetxa • La Muralla • Zeruko Taberna • La Fábrica • La Jarana Taberna • Urepel • Bar Néstor • Xarma Cook & Culture • Borda Berri • Juanito Kojua • Casa Urola • Astelena 1997 Our Favorites Stops In Gros - Page 25 • Aldanondo La Rampa • Ni Neu • • Gatxupa Gastronomic Splurges Outside The City - Page 41 • Topa Sukaldería • Restaurant Fagollaga • Ramuntxo Berri • Asador Bedua • Bodega Donostiarra