Epidemiological Findings of Major Chemical Attacks in the Syrian War Are Consistent with Civilian Targeting: a Short Report Jose M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

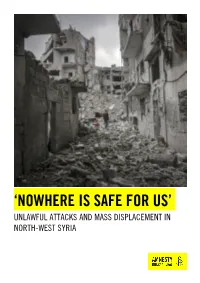

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

The Aid in Danger Monthly News Brief, Nigeria February 2017

The Aid in Danger February Monthly News Brief 2017 Security Incidents This monthly digest comprises threats and incidents of violence affecting the delivery Africa of humanitarian assistance. It Cameroon is prepared by Insecurity 31 January 2017: In the vicinity of Hosere Jongbi area, near the town Insight from information of Kontcha, an unknown armed group attacked a UN Technical available in open sources. Monitoring Team, killing five individuals, including a UN independent contractor, three Nigerians and one Cameroonian, and injuring All decisions made on the several others. Sources: Premium Times and The News basis of, or with consideration to, such information remains Central African Republic the responsibility of their 02 February 2017: In Bocaranga sub-prefecture, Ouham-Pendé respective organisations. prefecture, an unspecified armed group attacked and plundered the compounds of three non-governmental organisations (NGOs): Editorial team: MENTOR, CORDAID and DRC. Source: RJDH Christina Wille Insecurity Insight 10 February 2017: In the capital Bangui, gunmen stormed a hospital Larissa Fast in PK5 neighbourhood twice within five days to kill patients. Source: Insecurity Insight The Citizen Adelicia Fairbanks European Interagency Security Democratic Republic of the Congo Forum (EISF) 22 February 2017: In Kasai Oriental and Upper Katanga, unidentified assailants broke into and vandalised a number of churches engaged Research team: in poverty work for the local population. Source: Radio Okapi Insecurity Insight Kenya Visit our website to download 24 February 2017: In Baringo county, local residents blocked seven previous Aid in Danger Kenya Red Cross Society vehicles carrying 96.8 metric tonnes of Monthly News Briefs. humanitarian assistance, which led to looting of relief aid and harassment of aid staff. -

Critical Evaluation of Proven Chemical Weapon Destruction Technologies

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 74, No. 2, pp. 187–316, 2002. © 2002 IUPAC INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY ORGANIC AND BIOMOLECULAR CHEMISTRY DIVISION IUPAC COMMITTEE ON CHEMICAL WEAPON DESTRUCTION TECHNOLOGIES* WORKING PARTY ON EVALUATION OF CHEMICAL WEAPON DESTRUCTION TECHNOLOGIES** CRITICAL EVALUATION OF PROVEN CHEMICAL WEAPON DESTRUCTION TECHNOLOGIES (IUPAC Technical Report) Prepared for publication by GRAHAM S. PEARSON1,‡ AND RICHARD S. MAGEE2 1Department of Peace Studies, University of Bradford, Bradford, West Yorkshire BD7 1DP, UK 2Carmagen Engineering, Inc., 4 West Main Street, Rockaway, NJ 07866, USA *Membership of the IUPAC Committee is: Chairman: Joseph F. Burnett; Members: Wataru Ando (Japan), Irina P. Beletskaya (Russia), Hongmei Deng (China), H. Dupont Durst (USA), Daniel Froment (France), Ralph Leslie (Australia), Ronald G. Manley (UK), Blaine C. McKusick (USA), Marian M. Mikolajczyk (Poland), Giorgio Modena (Italy), Walter Mulbry (USA), Graham S. Pearson (UK), Kurt Schaffner (Germany). **Membership of the Working Group was as follows: Chairman: Graham S. Pearson (UK); Members: Richard S. Magee (USA), Herbert de Bisschop (Belgium). The Working Group wishes to acknowledge the contributions made by the following, although the conclusions and contents of the Technical Report remain the responsibility of the Working Group: Joseph F. Bunnett (USA), Charles Baronian (USA), Ron G. Manley (OPCW), Georgio Modena (Italy), G. P. Moss (UK), George W. Parshall (USA), Julian Perry Robinson (UK), and Volker Starrock (Germany). ‡Corresponding author Republication or reproduction of this report or its storage and/or dissemination by electronic means is permitted without the need for formal IUPAC permission on condition that an acknowledgment, with full reference to the source, along with use of the copyright symbol ©, the name IUPAC, and the year of publication, are prominently visible. -

Field Developments in Idleb 51019

Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western Situation Report and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 May 2019 Aleppo Countrysides During March and April 2019 the Information Management Unit 1 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 The Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU) aims to strengthen the decision-making capacity of aid actors responding to the Syrian crisis. This is done through collecting, analyzing and sharing information on the humanitarian situation in Syria. To this end, the Assistance Coordination Unit through the Information Management Unit established a wide net- work of enumerators who have been recruited depending on specific criteria such as education level, association with information sources and ability to work and communicate under various conditions. IMU collects data that is difficult to reach by other active international aid actors, and pub- lishes different types of information products such as Need Assessments, Thematic Reports, Maps, Flash Reports, and Interactive Reports. 2 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western Situation Report and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 May 2019 During March and April 2019 3 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 01. The Most Prominent Shelling Operations During March and April 2019, the Syrian regime and its Russian ally shelled Idleb Governorate and its adjacent countrysides of Aleppo and Hama governorates, with hundreds of air strikes, and artillery and missile shells. The regime bombed 14 medical points, including hospitals and dispensaries; five schools, including a kinder- garten; four camps for IDPs; three bakeries and two centers for civil defense, in addition to more than a dozen of shells that targeted the Civil Defense volunteers during the evacuation of the injured and the victims. -

Nerve Agent - Lntellipedia Page 1 Of9 Doc ID : 6637155 (U) Nerve Agent

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of MILLIONS of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com Nerve Agent - lntellipedia Page 1 of9 Doc ID : 6637155 (U) Nerve Agent UNCLASSIFIED From lntellipedia Nerve Agents (also known as nerve gases, though these chemicals are liquid at room temperature) are a class of phosphorus-containing organic chemicals (organophosphates) that disrupt the mechanism by which nerves transfer messages to organs. The disruption is caused by blocking acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that normally relaxes the activity of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. ...--------- --- -·---- - --- -·-- --- --- Contents • 1 Overview • 2 Biological Effects • 2.1 Mechanism of Action • 2.2 Antidotes • 3 Classes • 3.1 G-Series • 3.2 V-Series • 3.3 Novichok Agents • 3.4 Insecticides • 4 History • 4.1 The Discovery ofNerve Agents • 4.2 The Nazi Mass Production ofTabun • 4.3 Nerve Agents in Nazi Germany • 4.4 The Secret Gets Out • 4.5 Since World War II • 4.6 Ocean Disposal of Chemical Weapons • 5 Popular Culture • 6 References and External Links --------------- ----·-- - Overview As chemical weapons, they are classified as weapons of mass destruction by the United Nations according to UN Resolution 687, and their production and stockpiling was outlawed by the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993; the Chemical Weapons Convention officially took effect on April 291997. Poisoning by a nerve agent leads to contraction of pupils, profuse salivation, convulsions, involuntary urination and defecation, and eventual death by asphyxiation as control is lost over respiratory muscles. -

Modern Chemical Weapons

Modern Chemical Weapons Modern Chemical Weapons causes serious diseases like cancer and serious birth defects in newly born Large scale chemical weapons were children. first used in World War One and have been used ever since. About 100 years ago Modern warfare has developed significantly since the early 20th century Early chemical weapons being used but the use of toxic chemicals to kill around a hundred years ago included: and badly injure is still very much in use tear gas, chlorine gas, mustard gas today. There have been reports of and phosgene gas. Since then, some chemical weapon attacks in Syria of the same chemicals have been during 2016. Chemical weapons have used in more modern warfare, but also been the choice of terrorists other new chemical weapons have because they are not very expensive also been developed. and need very little specialist knowledge to use them. These Chlorine gas (Cl2) weapons can cause a lot of causalities as well as fatalities, but also There have been reports of many spread panic and fear. chlorine gas attacks in Syria since 2013. It is a yellow-green gas which has a very distinctive smell like bleach. However, it does not last very long and therefore it is sometimes very difficult to prove it has been used during an attack. Victims would feel irritation of the eyes, nose, throat and lungs when they inhale it in large enough quantities. In even larger quantities it can cause the death of a person by suffocation. Mustard gas (C4H8Cl2S) There are reports by the United Nations (UN) of terrorist groups using Mustard Agent Orange (mixture of gas during chemical attacks in Syria. -

Syrian Voices Art – Theory for Syria by Róza El-Hassan Bloody Peace By

Syrian Voices Art – Theory for Syria By Róza El-Hassan Bloody Peace By Shadi Alshhadeh Varvara Stepanova ‘Future is our only goal’, 1921 by Ben Vautier,artist born 1936 Ben Vautier •Kartoneh from Deir El Zor •Turn right and after one kilometer you arrive to the city of Deir •El Zor. +18 is for graphic scenes Kartoneh fro Deir EL Zor, Syria Halfaya, justice will be inflour- December 23 Dayer Elzour. our crave,weather its ade of dust or flour december 23 Deir El Zor because they deserve life - the week of demanding detained people from Syrians prisons Halfaya, justice will be inflour- December 23 Dayer Elzour. our crave,weather its ade of dust or flour december 23 Deir El Zor Dayer Elzour will remain a sign of difference in the world of pommegrate Kartoneh from Deir El Zor, Kartoon pain, 2013 Pigeon by anonymous photographer Lens Binnishi, Binnish city, Northern Syria, Idlib Region 2013 The word “Steadfast” in Arabic, collective body-art action, Binnish city, Northern Syria , From website: Coordinators of the revolution in the city of Binnish 2012 Liberty Statue made in Homs, 2012 Sculpturer makes objects of empty rocket shells and bullets http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jP_takNr-as Grafitty by Crazy Nano, Daraa, Southern Syria, 2012 Faculty of Art, lecture room in Aleppo University after the massacre caused by rocket in January 2013 Flash-mob – sit in protest action by students at Damascus university in solidarity with the sieged cities, beginning of 2012 Ali Ferzat, Syrian Caricaturist, January 2013 Four Brides of Peace, Damascus. Autumn 2012 - Arrested during the action and released after 48 days. -

Health Aspects of Biological and Chemical Weapons

[cover] WHO guidance SECOND EDITION WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA DRAFT MAY 2003 [inside cover] PUBLIC HEALTH RESPONSE TO BIOLOGICAL AND CHEMICAL WEAPONS DRAFT MAY 2003 [Title page] WHO guidance SECOND EDITION Second edition of Health aspects of chemical and biological weapons: report of a WHO Group of Consultants, Geneva, World Health Organization, 1970 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA 2003 DRAFT MAY 2003 [Copyright, CIP data and ISBN/verso] WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN xxxxx First edition, 1970 Second edition, 2003 © World Health Organization 1970, 2003 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). -

Security Council Distr.: General 24 August 2016

United Nations S/2016/738/Rev.1 Security Council Distr.: General 24 August 2016 Original: English Letter dated 24 August 2016 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey herewith the third report of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism. I should be grateful if the present letter and the report could be brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 16-14878 (E) 140916 *1614878* S/2016/738/Rev.1 Letter dated 24 August 2016 from the Leadership Panel of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons- United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism addressed to the Secretary-General The Leadership Panel of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism has the honour to transmit the Mechanism’s third report pursuant to Security Council resolution 2235 (2015). The report provides an update on the activities of the Mechanism up to 19 August 2016. It also outlines the concluding assessments of the Leadership Panel to date, on the basis of the results of the investigation into the nine selected cases of the use of chemicals as weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic. The Leadership Panel wishes to thank the Secretary-General for the confidence placed in it. The Panel appreciates the indispensable support provided by the Secretariat, including the Office for Disarmament Affairs, the Department for Political Affairs and the Office of Legal Affairs, and the United Nations officials who have assisted the Mechanism in New York, Geneva and Damascus. -

Attacks on Health Care July Monthly News Brief 2019

Attacks on Health Care July Monthly News Brief 2019 SHCC Attacks on Health Care This monthly digest The section aligns with the definition of attacks on health care used by the comprises threats and (SHCC). Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition violence as well as Please also see WHO SSA table on the last page of this document protests and other events affecting the delivery of Africa and access to health care. Burkina Faso 26 July 2019: In Konga, Gomboro district, Sourou province, suspected Katiba Macina militants reportedly kidnapped the manager of a It is prepared by pharmacy at an unnamed medical centre. Source: ACLED1 Insecurity Insight from information available in 13 July 2019: In Noukeltouoga, Gourma province, Est region, open sources. suspected JNIM and/or ISGS militants reportedly kidnapped a vaccination volunteer. Source: ACLED1 All decisions made, on the Cameroon basis of, or with 17 July 2019: In Bamenda, Mezam district, Nord-Ouest province, two consideration to, such doctors were reportedly kidnapped by an unidentified armed group information remains the and released 24 hours later. Sources: Maikemsdairy and Journal du responsibility of their Cameroun respective organisations. Central African Republic 05 July 2019: In Ouham prefecture, two national aid workers for an Data from the Attacks on INGO were reportedly assaulted while transporting two patients on Health Care Monthly motorcycles in the Ouham prefecture. The aid workers were ambushed, News Brief is available on robbed, and assaulted by armed men suspected to be MPC/FPRC. HDX Insecurity Insight. Source: AWSD2 Democratic Republic of the Congo Subscribe here to receive 13-14 July 2019: In Mukulia village, North Kivu province, unidentified monthly reports on attackers killed two national Ebola health workers for unascertained insecurity affecting the reasons. -

Countering the Use of Chemical Weapons in Syria: Options for Supporting International Norms and Institutions

EU Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Consortium NON-PROLIFERATION AND DISARMAMENT PAPERS Promoting the European network of independent non-proliferation and disarmament think tanks No. 63 June 2019 COUNTERING THE USE OF CHEMICAL WEAPONS IN SYRIA: OPTIONS FOR SUPPORTING INTERNATIONAL NORMS AND INSTITUTIONS una becker-jakob* INTRODUCTION SUMMARY For more than six years the people of Syria and the Chemical weapons are banned by international law. international community have had to face the fact Nonetheless, there have been numerous alleged and proven that chemical weapons have become part of the chemical attacks during the Syrian civil war. The international community has found ways to address this weapons arsenal in the Syrian civil war. By using these problem, but it has not managed to exclude the possibility weapons, those responsible—the Syrian Government of further chemical attacks once and for all. Nor has it included—have violated one of the most robust taboos created accountability for the perpetrators. The in international humanitarian law. In recent years, establishment in 2018 of the Investigation and the international community, the United Nations Identification Team within the Organisation for the and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) is a step in the Weapons (OPCW) have found creative ways to address right direction, but it came at the price of increased this situation, but no strategy has so far succeeded in polarization among member states. To maintain the truly redressing