Ongoing Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English

联合国 S/2012/515 安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信 奉我国政府指示,并继我 2012 年 4 月 16 日至 20 日和 23 日至 25 日、5 月 7 日、11 日、14 日至 16 日、18 日、21 日、24 日、29 日和 31 日、6 月 1 日、4 日、 6 日、7 日、11 日、19 日、20 日、25 日、27 日和 28 日的信,谨随函附上 2012 年 6 月 27 日武装团伙在叙利亚境内违反停止暴力规定行为的详细清单(见附件)。 请将本信及其附件作为安全理事会的文件分发为荷。 常驻代表 大使 巴沙尔·贾法里(签名) 12-56095 (C) 231012 241012 *1256095C* S/2012/515 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信的附件 [Original: Arabic] Wednesday, 27 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 27 June 2012 at 2200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in the area of Qastal. 2. At 0200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement officers in the vicinity of the Industry School in Ra's al-Nab‘, Qatana. 3. At 0630 hours, an armed terrorist group attacked and detonated explosive devices at the Syrian Ikhbariyah satellite channel building in Darwasha in the vicinity of Khan al-Shaykh, killing Corporal Ma'mun Awasu, Conscript Tal‘at al-Qatalji, Conscript Mash‘al al-Musa and Conscript Abdulqadir Sakin. Several employees were also killed, including Sami Abu Amin, Muhammad Shamsah and employee Zayd Ujayl. Another employee was wounded , 11 law enforcement officers were abducted, and 33 rifles were seized. 4. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group opened on fire on and fired rocket-propelled grenades at a law enforcement checkpoint in Hurnah between Ma‘araba bridge and Tall. -

Second Quarterly Report on Besieged Areas in Syria May 2016

Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Colophon ISBN/EAN:9789492487018 NUR 698 PAX serial number: PAX/2016/06 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in Washington, DC. TSI was founded in 2015 in response to a recognition that today, almost six years into the Syrian conflict, information and understanding gaps continue to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the unfolding crisis. Our aim is to address these gaps by empowering decision-makers and advancing the public’s understanding of the situation in Syria by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Photo cover: Women and children spell out ‘SOS’ during a protest in Daraya on 9 March 2016, (Source: courtesy of Local Council of Daraya City) Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Table of Contents 4 PAX & TSI ! Siege Watch Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 8 Key Findings and Recommendations 9 1. Introduction 12 Project Outline 14 Challenges 15 General Developments 16 2. Besieged Community Overview 18 Damascus 18 Homs 30 Deir Ezzor 35 Idlib 38 Aleppo 38 3. Conclusions and Recommendations 40 Annex I – Community List & Population Data 46 Index of Maps & Tables Map 1. -

Country of Origin Information Report Syria June 2021

Country of origin information report Syria June 2021 Page 1 of 102 Country of origin information report Syria | June 2021 Publication details City The Hague Assembled by Country of Origin Information Reports Section (DAF/AB) Disclaimer: The Dutch version of this report is leading. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands cannot be held accountable for misinterpretations based on the English version of the report. Page 2 of 102 Country of origin information report Syria | June 2021 Table of contents Publication details ............................................................................................2 Table of contents ..........................................................................................3 Introduction ....................................................................................................5 1 Political and security situation .................................................................... 6 1.1 Political and administrative developments ...........................................................6 1.1.1 Government-held areas ....................................................................................6 1.1.2 Areas not under government control. ............................................................... 11 1.1.3 COVID-19 ..................................................................................................... 13 1.2 Armed groups ............................................................................................... 13 1.2.1 Government forces ....................................................................................... -

Syria Sitrep October 28

Syria Situation Report: October 28 - November 10, 2020 1 Oct. 29 - Nov. 1: ISIS Continues Assassination Campaign against Leaders 5 Nov. 4 - 7: ISIS Attack Cells May Have of Security and Governance Institutions in Eastern Syria. ISIS claimed the Strengthened in Aleppo Province. ISIS claimed assassination of the director of the oil department within the Syrian Democratic Forces responsibility for an improvised explosive device (IED) (SDF)-supported Deir e-Zor Civil Council in al-Sabha on October 29. Possible ISIS that killed a commander of the Turkish-backed Faylaq militants attempted and failed to assassinate Abu Khawla, the head of the Deir e-Zor al-Sham in al-Bab on November 4. ISIS militants Military Council in Hasakah city, Hasakah Province, on November 1. ISIS also claimed detonated an IED in al-Bab on November 7, killing three the assassination of Commander Hafal Riad of the Kurdish Internal Security Forces in Free Syrian Police officers. On the same day, ISIS Markadah, Hasakah Province, on the same day. claimed responsibility for an IED that killed one and injured an unknown number of people in 2 Nov. 2: Iranian-affiliated Militiaman Shamarikh. This amount of Confesses Plot to Degrade Security Situation 4 Qamishli ISIS activity is unusual in by Assassinating Key Figures. Authorities Turkish-controlled Aleppo arrested Radwan al-Hajji when he attempted to 5 Province and may indicate assassinate Hammouda Abu Ashour, the leader of Manbij increased capabilities in the the Al-Furqan Brigade, in Kanaker, Damascus 5 Hasakah region or that ISIS is transitioning Province. Al-Hajji revealed a list of 17 Kanaker 1 this area to an attack zone. -

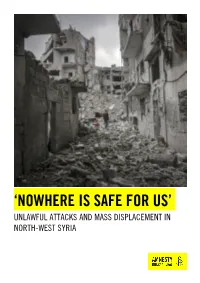

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

The Political Direction of Which Ariel Sharon's Disengagement Plan Forms a Part Is the Most Significant Development in Israe

FRAGMENTED SYRIA: THE BALANCE OF FORCES AS OF LATE 2013 By Jonathan Spyer* Syria today is divided de facto into three identifiable entities. These three entities are: first, the Asad regime itself, which has survived all attempts to divide it from within. The second area is the zone controlled by the rebels. In this area there is no central authority. Rather, the territory is divided up into areas controlled by a variety of militias. The third area consists of majority-Kurdish northeast Syria. This area is under the control of the PYD (Democratic Union Party), the Syrian franchise of the PKK. This article will look into how this situation emerged, and examine its implications for the future of Syria. As the Syrian civil war moves toward its The emergence of a de facto divided Syria fourth anniversary, there are no signs of is the result first and foremost of the Asad imminent victory or defeat for either of the regime’s response to its strategic predicament sides. The military situation has reached a in the course of 2012. By the end of 2011, the stalemate. The result is that Syria today is uprising against the regime had transformed divided de facto into three identifiable entities, from a largely civilian movement into an each of which is capable of defending its armed insurgency, largely because of the existence against threats from either of the regime’s very brutal and ruthless response to others. civilian demonstrations against it. This These three entities are: first, the Asad response did not produce the decline of regime itself, which has survived all attempts opposition, but rather the formation of armed to divide it from within. -

Deraa Province: Conflict Dynamics and the Role of Civil Society

Conflict Research Programme Deraa Province: Conflict Dynamics and the Role of Civil Society Sohaib al-Zoabi April 2020 2 Deraa Province: Conflict Dynamics and the Role of Civil Society 1. Executive Summary 2015 had taken control of the majority of Deraa is known to be the cradle of the the two southern provinces of Deraa and Syrian uprising of 2011. There were many Quneitra. The situation remained largely reasons for the province’s increased unchanged until the De-escalation popular resentment against the political Agreement of May 2017, which led to a regime in Syria, including the regime’s relative decrease in the intensity of hardline security policies; its monopoly of violence, and included all southern areas. the public sphere in the interest of a tight However, the situation shifted rapidly once circle of local middlemen directly linked again at the end of June 2018, when the with the security apparatus; the continued Syrian regime, backed by the Russian tightening of the margin of basic freedoms; forces, began a brutal military campaign and the uneven development between against Deraa. This campaign ended in Deraa’s rural and urban areas. what is known as the Deraa Reconciliation The protest movement in the Deraa Agreement of June 2018, between the province is distinct given the role played by opposition forces and the regime, carried Deraa city in the uprising, which preceded out under the direct oversight of Russia. the involvement of the surrounding rural This agreement stipulated return of the areas. whole southern area to regime control, with the integration of opposition military The peaceful nature of the uprising in factions into the Russian-backed Fifth Deraa helped to strengthen of the civil Corps. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012

United Nations S/2012/550 Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25, 27 and 28 June, and 2, 3, 9 and 11 July 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 9 July 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-58099 (E) 271112 281112 *1258099* S/2012/550 Annex to the identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Monday, 9 July 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. At 2200 hours on it July 2012, an armed terrorist group abducted Chief Warrant Officer Rajab Ballul in Sahnaya and seized a Government vehicle, licence plate No. 734818. 2. At 0330 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on the law enforcement checkpoint of Shaykh Ali, wounding two officers. 3. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device as a law enforcement overnight bus was passing the Artuz Judaydat al-Fadl turn-off on the Damascus-Qunaytirah road, wounding three officers. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Syrian Arab Republic News Focus: Syria https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria (OSES) https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/ Syrian Civil Society Voices: A Critical Part of the Political Process (In: Politically Speaking, 29 June 2021): https://bit.ly/3dYGqko Syria: a 10-year crisis in 10 figures (OCHA, 12 March 2021): https://www.unocha.org/story/syria-10-year-crisis-10-figures Secretary-General announces appointments to Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Syria Humanitarian Deconfliction System (SG/SM/20548, 21 January 2021): https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20548.doc.htm Secretary-General establishes board to investigate events in North-West Syria since signing of Russian Federation-Turkey Memorandum on Idlib (SG/SM/19685, 1 August 2019): https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19685.doc.htm Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels V Conference, 29-30 March 2021 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2021/03/29-30/ Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels IV Conference, 30 June 2020: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2020/06/30/ Third Brussels conference “Supporting the future of Syria and the region”, 12-14 March 2019: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2019/03/12-14/ Second Brussels Conference "Supporting the future of Syria and the region", 24-25 April 2018: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2018/04/24-25/ -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International Is a Global Movement of More Than 7 Million People Who Campaign for a World Where Human Rights Are Enjoyed by All

‘LEFT TO DIE UNDER SIEGE’ WAR CRIMES AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: MDE 24/2079/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Residents search through rubble for survivors in Douma, Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. Activists said the damage was the result of an air strike by forces loyal to President Bashar