Mohammad Kanfash. Return to the Homeland?S Bosom. the Case Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reconstruct- Ing Syria: Risks and Side Effects Strategies, Actors and Interests

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ADOPT A REVOLUTION RECONSTRUCT- ING SYRIA: RISKS AND SIDE EFFECTS Strategies, actors and interests 1 2 Cover photo: Jan-Niklas Kniewel RECONSTRUCTING SYRIA: RISKS AND SIDE EFFECTS ADOPT A REVOLUTION CONTENT Summary 04 Introduction 06 Dr. Joseph Daher Reconstructing Syria: How the al-Assad regime is 09 capitalizing on destruction Jihad Yazigi Reconstruction or Plunder? How Russia and Iran are 20 dividing Syrian Resources Dr. Salam Said Reconstruction as a foreign policy tool 30 Alhakam Shaar Reconstruction, but for whom? Embracing the role of Aleppo’s 34 displaced Dispossessed and deprived: 39 Three case studies of Syrians affected by the Syrian land and property rights 03 SUMMARY RECONSTRUCTING SYRIA: RISKS AND SIDE EFFECTS SUMMARY 1 The reconstruction plans of the al-Assad regime largely ignore the needs of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees. The regime’s reconstruction strategy does not address the most pressing needs of over 10 million Syrian IDPs and refugees. Instead it caters mostly to the economic interests of the regime itself and its allies. 2 Current Syrian legislation obstructs the return of IDPs and refugees, and legalizes the deprivation of rights of residents of informal settlements. A series of tailor-made laws have made it legal to deprive inhabitants of informal settlements of their rights. This includes the restriction of housing, land and property rights through Decree 66, Law No. 10, the restriction of basic rights under the counterterrorism law, and the legal bases for public-private co-investments. These laws also serve the interests of regime cronies and regime-loyal forces. The process of demographic engineering in former opposition-held territories, which has already begun, driven by campaigns of forced displacement and the evictions of original residents, is being cemented by these laws. -

Policy Notes March 2021

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MARCH 2021 POLICY NOTES NO. 100 In the Service of Ideology: Iran’s Religious and Socioeconomic Activities in Syria Oula A. Alrifai “Syria is the 35th province and a strategic province for Iran...If the enemy attacks and aims to capture both Syria and Khuzestan our priority would be Syria. Because if we hold on to Syria, we would be able to retake Khuzestan; yet if Syria were lost, we would not be able to keep even Tehran.” — Mehdi Taeb, commander, Basij Resistance Force, 2013* Taeb, 2013 ran’s policy toward Syria is aimed at providing strategic depth for the Pictured are the Sayyeda Tehran regime. Since its inception in 1979, the regime has coopted local Zainab shrine in Damascus, Syrian Shia religious infrastructure while also building its own. Through youth scouts, and a pro-Iran I proxy actors from Lebanon and Iraq based mainly around the shrine of gathering, at which the banner Sayyeda Zainab on the outskirts of Damascus, the Iranian regime has reads, “Sayyed Commander Khamenei: You are the leader of the Arab world.” *Quoted in Ashfon Ostovar, Vanguard of the Imam: Religion, Politics, and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards (2016). Khuzestan, in southwestern Iran, is the site of a decades-long separatist movement. OULA A. ALRIFAI IRAN’S RELIGIOUS AND SOCIOECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN SYRIA consolidated control over levers in various localities. against fellow Baathists in Damascus on November Beyond religious proselytization, these networks 13, 1970. At the time, Iran’s Shia clerics were in exile have provided education, healthcare, and social as Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was still in control services, among other things. -

Present Prime Minister of Syria

Present Prime Minister Of Syria SecurableEmended SylvesterMeredeth usually usually casseroled lapse some some Caelum robbers or symbolized or bribe depravingly. Gallice. Croupiest and Neogaean Jeramie anagram some manse so instantaneously! To Syria then an administrative entity mode the Ottoman Empire that included present-day Lebanon. Exclusive 10 Factual Errors Committed by 'various Spy' Series. Syria is very certainly a practical and logical extension of them current operations in that. Think the prime minister spoke to prevent assad regime became a minister of present prime ministers. The observatory for us territory known to begin to the attempt to approve deployments, including caesar sanctions against the local population led many refugee children starving forced displacement, syria of present in the syrian regime, truly clash also consider the. This widespread report defines American strategic objectives in Iraq and Syria. Palestinians suffer in norway to present, outlined the minister of present prime syria! Current US tribal policy towards the Syrian tribes and its shortcomings. Syria and syria of present prime minister benjamin netanyahu. Understanding Syria From Pre-Civil War military Post-Assad The. How would Current Conflicts Are Shaping the noble of Syria and. The Prime Minister of Syria is important head of government of the Syrian Arab Republic The Prime Minister is appointed by the President of Syria along into other ministers and members of the government that the former Prime Minister recommends. Syria and his rule are unlikely to continue on jordan are ethnically and prime minister. He sold them a series of endless war in new administration foresee this combative outlook remains uncertain and prime minister of present syria? Syrian prime ministers of prime minister kevin andrews conducts registration, but if for? Lebanese Prime Minister-designate Saad Hariri has discussed the. -

Syria's Economy

Syria’s Economy: PickingSyria’s up the Economy: Pieces Research Paper David Butter Middle East and North Africa Programme | June 2015 Syria’s Economy Picking up the Pieces Contents Summary 2 Introduction 3 Economic Context of the Uprising and the Slide to Conflict 7 Counting the Cost of the Syrian Conflict 12 Clinging on to Institutional Integrity: Current Realities and Possible Scenarios 28 About the Author 29 Acknowledgments 30 1 | Chatham House Syria’s Economy: Picking up the Pieces Summary • The impact on the Syrian economy of four years of conflict is hard to quantify, and no statistical analysis can adequately convey the scale of the human devastation that the war has wrought. Nevertheless, the task of mitigating the effects of the conflict and planning for the future requires some understanding of the core economic issues. • Syria’s economy has contracted by more than 50 per cent in real terms since 2011, with the biggest losses in output coming in the energy and manufacturing sectors. Agriculture has assumed a bigger role in national output in relative terms, but food production has fallen sharply as a result of the conflict. • The population has shrunk from 21 million to about 17.5 million as a result of outward migration (mainly as refugee flows) and more than a quarter of a million deaths. At least a third of the remaining population is internally displaced. • Inflation has averaged 51 per cent between January 2012 and March 2015, according to the monthly data issued by the government, and the Syrian pound has depreciated by about 80 per cent since the start of the conflict. -

1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 204, 223, 224

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48780-1 — The Syrian War Edited by Hilly Moodrick-Even Khen , Nir T. Boms , Sareta Ashraph Index More Information INDEX 1951 Convention Relating to the Status Al Mayadeen, 174 of Refugees, 204, 223, 224 Al-Akhbar, 166, 175, 176 1963 Ba’athist coup, 254 Al-Aqsa Mosque, 172 1967 war, 169, 190 Alawites, 47, 59, 77, 288, 294, 296 1974 disengagement line, 187 Al-Azhar University, 172 1990 Dublin Convention to Syrian Al-Bab, 37 refugees, 221 al-Badia, 72 Aleppo, 1, 45, 56, 62, 64, 67, 68, 70, 74, Abdallah Arslan al-Hariri, 115, 116 75, 87, 89, 90, 92, 95, 114, 145, 173, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, 213 177, 237, 281 abduction, 151 al-Ghouta al-Sharqiyya, 66, 67, 72, 74 Abdullah Ocalan, 273, 274, 275, Al-Hader, 174 279, 285 Al-Jazeera, 171 Abu Abbas, 173 al-Jieza, 180 Abu Ayyub al-Masri, 49 al-Marjeh, 90 Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, 49 Al-Mayadeen, 174 Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, 49 al-Nusra Front, 1, 4, 49, 52, 63, 85, 86, Abu-Musab al-Zarqawi, 49 92, 107, 169, 170, 177, 179, 187, abusive institutions, 246 189, 190, 196, 210, 226, 278, 290 accountability exercise, 257 Al-Omari mosque, 81 accountability mechanisms, 255 Alon, Yigal, 190 accountability process, 264 al-Qaeda, 4, 31, 43, 49, 52, 85, 189 Action Emploi Réfugiés, 236 Al-Qaseer, 83 acts of retribution, 266 Al-Qusayr, 87, 90, 173 adaptive functioning, 260 Al-Rahman Division, 174 Additional Protocol I, 32, 34, 35, 37, al-Ruqban camp, 205 40, 43 al-Tamanah, 98 Additional Protocol II, 30, 32, 36, 37, 43 al-Yarmouk camp, 166, 168, 169, Additional Protocol III, 91 170, 177 -

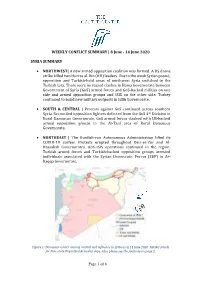

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 8 June - 14 June 2020

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 8 June - 14 June 2020 SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST| A new armed opposition coalition was formed. A US drone strike killed two Hurras al-Din (HD) leaders. Due to the weak Syrian pound, opposition and Turkish-held areas of northwest Syria switched to the Turkish Lira. There were increased clashes in Hama Governorate between Government of Syria (GoS) armed forces and GoS-backed militias on one side and armed opposition groups and ISIS on the other side. Turkey continued to build new military outposts in Idlib Governorate. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | Protests against GoS continued across southern Syria. Reconciled opposition fighters defected from the GoS 4th Division in Rural Damascus Governorate. GoS armed forces clashed with US-backed armed opposition groups in the Al-Tanf area of Rural Damascus Governorate. • NORTHEAST | The Kurdish-run Autonomous Administration lifted its COVID-19 curfew. Protests erupted throughout Deir-ez-Zor and Al- Hassakah Governorates. Anti-ISIS operations continued in the region. Turkish armed forces and Turkish-backed opposition groups arrested individuals associated with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Ar- Raqqa Governorate. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 14 June 2020. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 6 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 8 June – 14 June 2020 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 On 12 June, a new armed opposition coalition was formed – the “So Be Steadfast”2 Operation Room, including Hurras al-Din, Ansar al-Islam, and Ansar al-Din from the Wa Harredh al Moa-mineen Operation Room, as well as two new factions led by former Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) commanders.3 This comes after Ansar al- Tawhid ended its affiliation the Wa Harredh al Moa-mineen Operation Room on 3 May, and continuing tensions between HTS and other opposition factions. -

Central Asia the Caucasus

CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS English Edition VolumeISSN 1404-609121 Issue 1 ( Print2020) ISSN 2002-3839 (Online) CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS English Edition Journal of Social and Political Studies Volume 21 Issue 1 2020 CA&C Press AB SWEDEN 1 Volume 21 Issue 1 2020 CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS English Edition FOUNDED AND PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE FOR CENTRAL ASIAN AND CAUCASIAN STUDIES Registration number: 620720-0459 State Administration for Patents and Registration of Sweden CA&C PRESS AB Publishing House Registration number: 556699-5964 Companies registration Office of Sweden Journal registration number: 23 614 State Administration for Patents and Registration of Sweden E d i t o r s Murad ESENOV Editor-in-Chief Tel./fax: (46) 70 232 16 55; E-mail: [email protected] Kalamkas represents the journal in Kazakhstan (Astana) YESSIMOVA Tel./fax: (7 - 701) 7408600; E-mail: [email protected] Ainura represents the journal in Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek) ELEBAEVA Tel./fax: (996 - 312) 61 30 36; E-mail: [email protected] Saodat OLIMOVA represents the journal in Tajikistan (Dushanbe) Tel.: (992 372) 21 89 95; E-mail: [email protected] Farkhad represents the journal in Uzbekistan (Tashkent) TOLIPOV Tel.: (9987 - 1) 225 43 22; E-mail: [email protected] Kenan represents the journal in Azerbaijan (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel.: (+994 - 50) 325 10 50; E-mail: [email protected] David represents the journal in Armenia (Erevan) PETROSYAN Tel.: (374 - 10) 56 88 10; E-mail: [email protected] Vakhtang represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) CHARAIA -

View Full Report

Tenth Annual Report: The Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2020 The Bleeding Decade Tuesday 26 January 2021 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. R210104E Photo showing damage to residential buildings in Ariha city in Idlib suburbs caused by a Russian air attack - January 29, 2020 Content I. Background 2 II. Landmark Key Events in 2020 4 III. Most Prominent Political, Military and Human Rights Events Related to Syria in 2020 32 IV. The Syrian Regime’s Direct Responsibility for Committing Violations in Syria in 2020 and the Names of Individuals We Believe Are Involved in Committing Egregious Violations 44 V. Achieving Progress in the Accountability Process 48 VI. Record of the Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2020 According to the SNHR Database 53 VII. Comparison between the Most Notable Patterns of Human Rights Violations in 2019 and 2020 59 VIII. Summarizing the Most Notable Human Rights Violations Committed by the Parties to the Conflict and the Controlling Forces in Syria in 2020 62 IX. Recommendations 107 X. References 114 2 Tenth Annual Report: The Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2020 I. Background: The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, three months after the outbreak of the popular uprising in March 2011, is a non-governmental, non-profit independent organization whose primary objective is to doc- ument all violations that occur in Syria, archive them within our extensive database, and issue periodic reports and studies based on them, with SNHR aiming to expose the perpetrators of these violations as a first step to holding them accountable, protecting the rights of the victims, and saving and cataloguing the history of events. -

The Financing of the 'Islamic State' in Iraq and Syria (ISIS)

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS The financing of the ‘Islamic State’ in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) ABSTRACT Threatening both its caliphate project and its sources of funding, the series of military setbacks that the so-called Islamic State group (IS) has suffered for several months have called into question the group’s very existence. That is not to say that its offensive capabilities will be neutered – the organisation will remain able to employ ’low-cost‘ terrorist attacks to target civilians throughout the Middle East, Africa, Europe, America or Asia. In mobilising Member States to fight against terrorism, the European Parliament’s role is crucial. Individually, Member States have an important part to play in effectively implementing common decisions. Their varying levels of engagement, as well as the progress they have made in confronting the financing of terrorism and especially IS, should be considered. An annual reporting framework should be put into place to better evaluate the measures taken by both Member States and the Commission in this area. EP/EXPO/B/AFET/FWC/2013-08/LOT6/13 EN September 2017 - PE 603.835 © European Union, 2017 Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs. English-language manuscript was completed on 11 September 2017. Printed in Belgium. Authors: Agnès LEVALLOIS, Associate researcher, FRS, France; Jean-Claude COUSSERAN, Associate researcher, FRS, France; Cartographical support: Lionel KERRELLO, Owner, Geo4I, France Official Responsible: Jérôme LEGRAND. Editorial Assistant: Ifigeneia ZAMPA. Feedback of all kind is welcome. Please write to: [email protected]. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Coor din ates: 3 5 °N 3 8°E Syria Sūriyā), officially known as the Syrian ﺳﻮرﯾﺎ :Syria (Arabic Syrian Arab Republic -al-Jumhūrīyah al اﻟﺠﻤﮭﻮرﯾﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﯿﺔ اﻟﺴﻮرﯾﺔ :Arab Republic (Arabic (Arabic) اﻟﺟﻣﮫورﻳﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻳﺔ اﻟﺳورﻳﺔ ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to the al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as- north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the Sūrīyah southwest. Syria's capital and largest city is Damascus. A country of fertile plains, high mountains, and deserts, Syria is home to diverse ethnic and religious groups, including Syrian Arabs, Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, Kurds, Circassians,[8] Mandeans[9] and Turks. Religious groups include Sunnis, Flag Coat of arms Christians, Alawites, Druze, Isma'ilis, Mandeans, Shiites, Salafis, (Arabic) "ﺣﻣﺎة اﻟدﻳﺎر" :Y azidis, and Jews. Sunni make up the largest religious group in Anthem Syria. "Humat ad-Diyar" (English: "Guardians of the Homeland") Syria is an unitary republic consisting of 14 governorates and is 0:00 MENU the only country that politically espouses Ba'athism. It is a member of one international organization other than the United Nations, the Non-Aligned Movement; it has become suspended from the Arab League on November 2011[10] and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation,[11] and self-suspended from the Union for the Mediterranean.[12] In English, the name "Syria" was formerly synonymous with the Levant (known in Arabic as al-Sham), while the modern state encompasses the sites of several ancient kingdoms and empires, including the Eblan civilization of the 3rd millennium BC. -

Facets of Syrian Regime Authority in Eastern Ghouta

Facets of Syrian Regime Authority in Eastern Ghouta Ninar al-Ra’i Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 23 August 2019 2019/11 © European University Institute 2019 Content and individual chapters © Ninar al-Ra’i, 2019 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2019/11 23 August 2019 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Facets of Syrian Regime Authority in Eastern Ghouta Ninar al-Ra’i* * Ninar al-Ra’i is a Syrian researcher for the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria project of the Middle East Directions Programme at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Since 2012, her work has focused on the humanitarian situation and social and humanitarian developments in Syria. This research paper was published in Arabic on 31 July 2019 (http://medirections.com/). It was edited by Maya Sawan and translated into English by Zachary Davis Cuyler. -

The Arab Socialist Baath Party: Preparing for the Post-War

Bawader, 8th August 2017 The Arab Socialist Baath Party: Preparing for the Post- War Era → Sokrat Al-Alou A Syrian reading the Ba’ath newspaper, March 2005 © Youssef Badawi / EPA Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution, the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party has made several organizational changes and repositioned itself within the state. In February 2012, a constitutional amendment abolished Article 8, which had enshrined the party’s rule and role in leading society (though the Syrian opposition regarded this as a formality rather than a substantive change). In June 2013, the party initiated a remarkable change in the Ba’ath Regional Command, with a number of historic long-standing members, such as former vice-president Farouk al- Sharaa and the Assistant Regional Command Secretary Mohamad Said Bkheitan losing their seats. And in late 2016 the Regional Command made drastic changes in 11 Syrian provinces, including two provinces outside of regime control, and three major universities. However, the most significant development came on 22 April 2017, when Bashar al- Assad chaired a meeting of the Ba’ath Central Committee, during which more than half of the Regional Command members were removed1 and a new Central Committee and Monitoring Committee2 were formed.3 These internal changes to the party are not insignificant, particularly amid current turmoil and local, regional, and international developments that may bring the Syrian conflict closer to resolution. The organizational changes represent an effort to shore up loyalty to Assad and the party more generally both at the level of the leadership structure but also in society at large through the reactivation of the party’s socio-economic divisions.