Syria's Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria and Repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP

30.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 330/21 DECISIONS COUNCIL DECISION 2012/739/CFSP of 29 November 2012 concerning restrictive measures against Syria and repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, internal repression or for the manufacture and maintenance of products which could be used for internal repression, to Syria by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be particular Article 29 thereof, prohibited, whether originating or not in their territories. Whereas: The Union shall take the necessary measures in order to determine the relevant items to be covered by this paragraph. (1) On 1 December 2011, the Council adopted Decision 2011/782/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Syria ( 1 ). 3. It shall be prohibited to: (2) On the basis of a review of Decision 2011/782/CFSP, the (a) provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering Council has concluded that the restrictive measures services or other services related to the items referred to in should be renewed until 1 March 2013. paragraphs 1 and 2 or related to the provision, manu facture, maintenance and use of such items, to any natural or legal person, entity or body in, or for use in, (3) Furthermore, it is necessary to update the list of persons Syria; and entities subject to restrictive measures as set out in Annex I to Decision 2011/782/CFSP. (b) provide, directly or indirectly, financing or financial assistance related to the items referred to in paragraphs 1 (4) For the sake of clarity, the measures imposed under and 2, including in particular grants, loans and export credit Decision 2011/273/CFSP should be integrated into a insurance, as well as insurance and reinsurance, for any sale, single legal instrument. -

How Over-Compliance Limits Humanitarian Work on Syria Challenges of Fund Transfer for Non-Profit Organizations Working on Syria

Invisible Sanctions: How over-compliance limits humanitarian work on Syria Challenges of Fund Transfer for Non-Profit Organizations Working on Syria 1 Invisible Sanctions: How over-compliance limits humanitarian work on Syria Challenges of Fund Transfer for Non-Profit Organizations Working on Syria Principal Researcher: Dr. Joseph Daher Review and editing: Dr. Erica Moret IMPACT - Civil Society Research and Development e.V. Principal Researcher: Dr. Joseph Daher Review and editing: Dr. Erica Moret Graphic Design: Tammam Al-Omar Published by: IMPACT - Civil Society Research and Development e.V Keithstraße 10 , 10787 Berlin Not for Sale. IMPACT e.V - ©2020 All rights reserved, no part of this publication can be printed, reissued or used in any shape or form without the publisher’s prior written consent. The views and opinions expressed in this report are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of IMPACT e.V . Despite going to great lengths to verify the authenticity of the information contained in this report, IMPACT e.V cannot guarantee their total impartiality. Table of Contents Acknowledgement ................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive summary and Main Findings of the Research ............................................................................ 3 Added value to the literature ................................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations .................................................................................................................................. -

In Numbers Highlights

WFP Syria Crisis Regional Response Situation Report September 2018 In Numbers Highlights 5.6 million refugees from Syria • In September, WFP reached more than 3.2 million refugees – out of a total of 5.6 million registered Syrian refugees – and 3.2 million Syrian refugees assisted in July host community members across Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, USD 4.0 billion injected into local economies of and Turkey through various food and cash-based assistance Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey programmes under the Country Strategic Plan (CSPs) in Egypt and Lebanon, and Transitional Interim CSPs in the three through cash-based transfers, local food countries. procurement and other expenditure since 2012. • Self-organized refugee returns verified by UNHCR in 2018 totalled 28,251 as of September 2018. Results from UNHCR People assisted 49% 51% return intention surveys showed that voluntary repatriation in safety and dignity remains the preferred durable solution for September 2018 Syrian refugees in the region. Overall: Situation Update Regional Refugee US$ 4.4 billion and Resilience Plan Regional WFP share: • As of September 2018, there are around 5.6 million refugees (3RP) 2018-2019 US$ 1.5 billion from Syria in the neighbouring countries of Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. • According to UNHCR’s Return Perception and Intention WFP Net Funding Requirements Surveys conducted in 2018, 76 percent of Syrian refugees (November 2018 – April 2019)* hoped to return to Syria one day, up from 51 percent in 2017, while 19 percent noted that they do not want to come back. Voluntary repatriation in safety and dignity remains the Regional US$ 307.4 million preferred durable solution for Syrian refugees in the region. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

![585 Parts 1000–1009[Reserved] Part 1010](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0336/585-parts-1000-1009-reserved-part-1010-220336.webp)

585 Parts 1000–1009[Reserved] Part 1010

PARTS 1000–1009[RESERVED] 1010.440 Person outside the United States. Subpart E—Special Information Sharing PART 1010—GENERAL PROVISIONS Procedures To Deter Money Laun- dering and Terrorist Activity Subpart A—General Definitions 1010.500 General. Sec. 1010.505 Definitions. 1010.100 General definitions. 1010.520 Information sharing between gov- ernment agencies and financial institu- Subpart B—Programs tions. 1010.530 [Reserved] 1010.200 General. 1010.540 Voluntary information sharing 1010.205 Exempted anti-money laundering among financial institutions. programs for certain financial institu- tions. Subpart F—Special Standards of Diligence; 1010.210 Anti-money laundering programs. Prohibitions; and Special Measures 1010.220 Customer identification program 1010.600 General. requirements. SPECIAL DUE DILIGENCE FOR CORRESPONDENT Subpart C—Reports Required To Be Made ACCOUNTS AND PRIVATE BANKING ACCOUNTS 1010.300 General. 1010.605 Definitions. 1010.610 Due diligence programs for cor- 1010.301 Determination by the Secretary. respondent accounts for foreign financial 1010.305 [Reserved] institutions. 1010.306 Filing of reports. 1010.620 Due diligence programs for private 1010.310 Reports of transactions in currency. banking accounts. 1010.311 Filing obligations for reports of 1010.630 Prohibition on correspondent ac- transactions in currency. counts for foreign shell banks; records 1010.312 Identification required. concerning owners of foreign banks and 1010.313 Aggregation. agents for service of legal process. 1010.314 Structured transactions. 1010.640 [Reserved] 1010.315 Exemptions for non-bank financial SPECIAL MEASURES UNDER SECTION 311 OF THE institutions. USA PATRIOT ACT AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 1010.320 Reports of suspicious transactions. ACCESS TO FOREIGN BANK RECORDS 1010.330 Reports relating to currency in ex- cess of $10,000 received in a trade or busi- 1010.651 Special measures against Burma. -

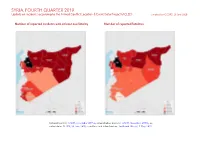

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

In Numbers Highlights

WFP Syria Crisis Regional Response Situation Report August 2018 In Numbers Highlights 5.6 million refugees from Syria • In August, WFP reached an estimated 3.0 million refugees – out of a total of 5.6 million registered Syrian refugees – and 3.0 million Syrian refugees assisted in July host community members across Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, USD 4.0 billion injected into local economies of and Turkey through various food and cash-based assistance Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey programmes under the Country Strategic Plan (CSPs) in Egypt and Lebanon and Transitional Interim CSPs in the three through cash-based transfers, local food countries. procurement and other expenditure since 2012. • Self-organized refugee returns registered by UNHCR in 2018 totalled 23,416 as of August 2018. The United Nations People assisted 49% 51% maintains that it does not promote refugee returns to Syria until conditions for voluntary, safe and dignified returns are in August 2018 place. Overall: Situation Update Regional Refugee US$ 4.4 billion and Resilience Plan Regional WFP share: • As of August 2018, there are around 5.6 million refugees from (3RP) 2018-2019 US$ 1.5 billion Syria in the neighbouring countries of Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. WFP Net Funding Requirements Jordan (October 2018 – March 2019)* • The Nasib border crossing between Syria and Jordan remains closed for now. Media reports in August said that the crossing is ready to receive Syrian refugees’ return from Jordan. Nasib Regional US$ 256.4 million has been vital for the transport of goods from Lebanon and Syria to Jordan and the Gulf states until it was closed off in Egypt US$ 14.8 million 2015, when it fell to Syrian opposition factions. -

Timeline of Key Events: March 2011: Anti-Government Protests Broke

Timeline of key events: March 2011: Anti-government protests broke out in Deraa governorate calling for political reforms, end of emergency laws and more freedoms. After government crackdown on protestors, demonstrations were nationwide demanding the ouster of Bashar Al-Assad and his government. July 2011: Dr. Nabil Elaraby, Secretary General of the League of Arab States (LAS), paid his first visit to Syria, after his assumption of duties, and demanded the regime to end violence, and release detainees. August 2011: LAS Ministerial Council requested its Secretary General to present President Assad with a 13-point Arab initiative (attached) to resolve the crisis. It included cessation of violence, release of political detainees, genuine political reforms, pluralistic presidential elections, national political dialogue with all opposition factions, and the formation of a transitional national unity government, which all needed to be implemented within a fixed time frame and a team to monitor the above. - The Free Syrian Army (FSA) was formed of army defectors, led by Col. Riad al-Asaad, and backed by Arab and western powers militarily. September 2011: In light of the 13-Point Arab Initiative, LAS Secretary General's and an Arab Ministerial group visited Damascus to meet President Assad, they were assured that a series of conciliatory measures were to be taken by the Syrian government that focused on national dialogue. October 2011: An Arab Ministerial Committee on Syria was set up, including Algeria, Egypt, Oman, Sudan and LAS Secretary General, mandated to liaise with Syrian government to halt violence and commence dialogue under the auspices of the Arab League with the Syrian opposition on the implementation of political reforms that would meet the aspirations of the people. -

Iranian Forces and Shia Militias in Syria

BICOM Briefing Iranian forces and Shia militias in Syria March 2018 Introduction In Iraq, another country where Iran has implemented its proxy policy, the Iranian On Wednesday, 28 February a US media outlet sponsored militias were not disbanded following reported that Iran was building a new military the defeat of ISIS but are standing as a united base 16 km northwest of the Syrian capital, list in the coming elections and will likely lead Damascus. The report included satellite images key institutions in the country. They are also of warehouses which could store short and protected in law as a permanently mobilised medium-range missiles that intelligence officials force, despite the fact that their leaders take said were capable of reaching any part of Israel. orders from Iran rather than the Government in The base, which is operated by the Iranian Baghdad. With the civil war in Syria far from Revolutionary Guard’s (IRGC) special operations over, Iran will likely seek to implement this “Iraq Quds Force, is similar to one established by model” in Syria in the future. the Iranians near the town of al-Kiswah, 15km southwest of Damascus, which was reportedly The sheer number of moving pieces in Syria targeted by Israeli fighter jets last December. – the regime heading south, Iran seeking to establish military bases, Israel becoming more This news followed a feature in the New York active in preventing the establishment of Shia Times which argued that Iran was “redrawing militias and Russia looking to maintain its the strategic map of the region” and that dozens dominance – are creating a combustible situation of bases in Syria were being operated by Iran with high potential for miscalculation, error and and its Shia militia network. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Powerbrokers

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

COUNCIL DECISION 2013/255/CFSP of 31 May 2013 Concerning Restrictive Measures Against Syria

L 147/14 EN Official Journal of the European Union 1.6.2013 COUNCIL DECISION 2013/255/CFSP of 31 May 2013 concerning restrictive measures against Syria THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, products which could be used for internal repression, to Syria by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be particular Article 29 thereof, prohibited, whether originating or not in their territories. Whereas: The Union shall take the necessary measures in order to (1) On 27 May 2013, the Council agreed to adopt for a determine the relevant items to be covered by this paragraph. period of 12 months restrictive measures against Syria in the following fields, as specified in Council Decision 2012/739/CFSP of 29 November 2012 concerning 2. It shall be prohibited to: restrictive measures against Syria ( 1): — export and import restrictions with the exception of arms and related material and equipment which (a) provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering might be used for internal repression; services or other services related to the items referred to in paragraph 1 or related to the provision, manufacture, main — restrictions on financing of certain enterprises; tenance and use of such items, to any natural or legal person, entity or body in, or for use in, Syria; — restrictions on infrastructure projects; — restrictions of financial support for trade; (b) provide, directly or indirectly, financing or financial assistance related to the items referred to in paragraph 1, — financial sector; including in particular grants, loans and export credit insurance, as well as insurance and reinsurance, for any — transport sector; sale, supply, transfer or export of such items, or for the provision of related technical assistance, brokering services or other services to any natural or legal person, entity or — restrictions on admission; body in, or for use in, Syria. -

Legislative Decree No. 33 the President of the Republic, Acting in Accordance with the Provisions of the Constitution, Hereby Decrees the Following

Legislative Decree No. 33 The President of the Republic, Acting in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution, Hereby decrees the following: Article 1 The following terms and expressions shall have, in the application of the present legislative decree, the respective meanings indicated below: A. Money-laundering: any comportment intended to conceal or alter the identity of funds having a connection with unlawful operations by disguising their origins so that they appear to have originated in lawful operations; B. Funds: assets of all types, whether tangible or intangible, movable or immovable, regardless of their manner of acquisition, and legal instruments or documents, whatever their form, including electronic and digital, constituting evidence of a right of ownership in such assets or a share therein, and everything arising from such ownership and any right connected therewith, including, by way of example and without limitation, national currency, foreign currencies, banking facilities, travellers cheques, bank cheques, money orders, shares, securities, bonds, documentary credits, drafts and bills of exchange; C. Illegal funds: funds obtained or resulting from the perpetration of any of the following offences, whether occurring in the territory of the Syrian Arab Republic or abroad: 1. The growing, manufacturing, smuggling or transporting of, or illegal trafficking in, narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances; 2. Acts committed by criminal associations, as provided in articles 325 and 326 of the Penal Code, and all offences internationally considered as constituting organized crime; 3. Terrorist offences, as provided in articles 304 and 305 of the Penal Code or in the international, regional or bilateral agreements to which Syria is a party; 4.