Facets of Syrian Regime Authority in Eastern Ghouta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English

联合国 S/2012/515 安全理事会 Distr.: General 19 October 2012 Chinese Original: English 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信 奉我国政府指示,并继我 2012 年 4 月 16 日至 20 日和 23 日至 25 日、5 月 7 日、11 日、14 日至 16 日、18 日、21 日、24 日、29 日和 31 日、6 月 1 日、4 日、 6 日、7 日、11 日、19 日、20 日、25 日、27 日和 28 日的信,谨随函附上 2012 年 6 月 27 日武装团伙在叙利亚境内违反停止暴力规定行为的详细清单(见附件)。 请将本信及其附件作为安全理事会的文件分发为荷。 常驻代表 大使 巴沙尔·贾法里(签名) 12-56095 (C) 231012 241012 *1256095C* S/2012/515 2012年7月2日阿拉伯叙利亚共和国常驻联合国代表给秘书长和安全 理事会主席的同文信的附件 [Original: Arabic] Wednesday, 27 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 27 June 2012 at 2200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on a military barracks headquarters in the area of Qastal. 2. At 0200 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on law enforcement officers in the vicinity of the Industry School in Ra's al-Nab‘, Qatana. 3. At 0630 hours, an armed terrorist group attacked and detonated explosive devices at the Syrian Ikhbariyah satellite channel building in Darwasha in the vicinity of Khan al-Shaykh, killing Corporal Ma'mun Awasu, Conscript Tal‘at al-Qatalji, Conscript Mash‘al al-Musa and Conscript Abdulqadir Sakin. Several employees were also killed, including Sami Abu Amin, Muhammad Shamsah and employee Zayd Ujayl. Another employee was wounded , 11 law enforcement officers were abducted, and 33 rifles were seized. 4. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group opened on fire on and fired rocket-propelled grenades at a law enforcement checkpoint in Hurnah between Ma‘araba bridge and Tall. -

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International Is a Global Movement of More Than 7 Million People Who Campaign for a World Where Human Rights Are Enjoyed by All

‘LEFT TO DIE UNDER SIEGE’ WAR CRIMES AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN EASTERN GHOUTA, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: MDE 24/2079/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Residents search through rubble for survivors in Douma, Eastern Ghouta, near Damascus. Activists said the damage was the result of an air strike by forces loyal to President Bashar -

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Weekly Conflict Summary | 1 - 8 September 2019

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 1 - 8 SEPTEMBER 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government of Syria (GoS) momentum slowed in Idleb this week, with no advances recorded. Further civilian protests denouncing Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS) took place in the northwest, in addition to pro-HTS and pro-Hurras al Din demonstrations. HTS and Jaish al Izza also launched a recruitment drive in the northwest. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | Attacks against GoS-aligned personnel and former opposition members continued in southern Syria, including two unusual attacks claimed by ISIS. GoS forces evicted civilians and appropriated several hundred houses in Eastern Ghouta. • NORTHEAST | The first joint US/Turkish ground patrol took place in Tal Abiad this week as part of an ongoing implementation of the “safe zone” in northern Syria. Low-level attacks against the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and SDF arrest operations of alleged ISIS members continued. Two airstrikes targeting Hezbollah and Iranian troops occurred in Abu Kamal. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 8 September 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 5 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 1 - 8 SEPTEMBER 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 GoS momentum in southern Idleb Governorate slowed this week, with no advances recorded. This comes a week after Damascus announced a ceasefire for the northwest on 31 August that saw a significant reduction in aerial activity, with no events recorded in September so far. However, GoS shelling continued impacting the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated enclave, with at least 26 communities2 affected (Figure 2). -

Timeline of Key Events: March 2011: Anti-Government Protests Broke

Timeline of key events: March 2011: Anti-government protests broke out in Deraa governorate calling for political reforms, end of emergency laws and more freedoms. After government crackdown on protestors, demonstrations were nationwide demanding the ouster of Bashar Al-Assad and his government. July 2011: Dr. Nabil Elaraby, Secretary General of the League of Arab States (LAS), paid his first visit to Syria, after his assumption of duties, and demanded the regime to end violence, and release detainees. August 2011: LAS Ministerial Council requested its Secretary General to present President Assad with a 13-point Arab initiative (attached) to resolve the crisis. It included cessation of violence, release of political detainees, genuine political reforms, pluralistic presidential elections, national political dialogue with all opposition factions, and the formation of a transitional national unity government, which all needed to be implemented within a fixed time frame and a team to monitor the above. - The Free Syrian Army (FSA) was formed of army defectors, led by Col. Riad al-Asaad, and backed by Arab and western powers militarily. September 2011: In light of the 13-Point Arab Initiative, LAS Secretary General's and an Arab Ministerial group visited Damascus to meet President Assad, they were assured that a series of conciliatory measures were to be taken by the Syrian government that focused on national dialogue. October 2011: An Arab Ministerial Committee on Syria was set up, including Algeria, Egypt, Oman, Sudan and LAS Secretary General, mandated to liaise with Syrian government to halt violence and commence dialogue under the auspices of the Arab League with the Syrian opposition on the implementation of political reforms that would meet the aspirations of the people. -

S Y R I a a R a B R E P U B L

PEOPLE IN NEED SO1 SO1RESPONSE RESPONSE DECEMBER CYCLE Food & Livelihood 8 5.78million Assistance 8.7 7 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m Million ORIGIN Food Basket Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2016 6 m m 5.96m 5.8m 6.16m 5.89m 4.43 1.35 September 2015 8.7 Million 5.74m 5.46m From within Syria From neighbouring Reached Beneficiaries 5 countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA September 2016 9.0 Million 4 102,724 Cash and Voucher 3 LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING OVERALL TARGET DECEMBER CYCLE RESPONSE So1 target FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 BENEFICIARIES Food Basket, Cash & Voucher 2 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher - 6.3 5.78 1 Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided life sustaining MODALITIES AND Million 7.5 Million Million Emergency 0 1.2 JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC BENEFICIARIES REACHED BY Response (92%) of SO1 Target 878,849 Million Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2016 Bread-Flour 280,385 598,464 From within Syria From neighbouring 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E countries 6 c Cizre- 1 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E g!42°0'0"E i 0 6 Kiziltepe-Ad c Nusaybin-Al Cizre- 2 1 l T U R K E Y Darbasiyah Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y g! i 0 r g! g! g! Ceylanpinar-Ras Nusaybin-Al 2 e Kiziltepe-Ad l Ayn al Arab Peshkabour b T U R K E Y Qamishli 93,306 T U R K E Y Al Yaroubiya Islahiye Al Ayn Darbasiyah b Karkamis-Jarabulus r g! Ayn al g! g! - Rabiaa g! Emergency Response with 39,000 ! Akcakale-Tall g! Ceylanpinar-Ras 54,306 e g g! Arab b Bab As g! Al Yaroubiya Ready to Eat Ration u m Abiad From neighbouring -

Syrian Armed Opposition Powerbrokers

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

Bashar Al-Assad's Struggle for Survival

Bashar al-Assad’s Struggle for Survival: Has the Miracle Occurred? Eyal Zisser The summer of 2014 marked the beginning of a turn in the tide of the civil war in Syria. The accomplishments of the rebels in battles against the regime tilted the scales in their favor and raised doubts regarding Bashar al-Assad’s ability to continue securing his rule, even in the heart of the Syrian state – the thin strip stretching from the capital Damascus to the city of Aleppo, to the Alawite coastal region in the north, and perhaps also to the city of Daraa and the Druze Mountain in the south. This changing tide in the Syrian war was the result of the ongoing depletion of the ranks of the Syrian regime and the exhaustion of the manpower at its disposal. Marked by fatigue and low morale, Bashar’s army was in growing need of members of his Alawite community who remained willing to fight and even die for him, as well as the Hizbollah fighters who were sent to his aid from neighboring Lebanon. The rebels, on the other hand, proved motivated, determined, and capable of perseverance. Indeed, they succeeded in unifying their ranks, and today, in contrast to the hundreds of groups that had been operating throughout the country, there are now only a few groups operating – all, incidentally, of radical Islamic character. Countries coming to the aid of the rebels also included Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, who decided to topple the Assad regime and showed determination equal to that of Bashar’s allies – Iran, Hizbollah, and Russia. -

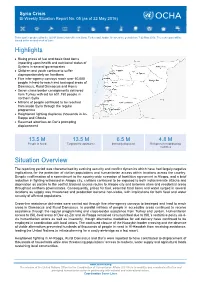

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations.