710 ATLANTIC REPORTER, 2D SERIES N. J. Suspensions. As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

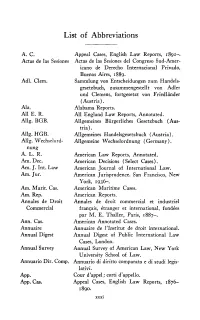

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r8gr-. Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, r88g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). All g. W echselord- Allgemeine Wechselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions ( Select Cases) . Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais, etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, r887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Camp. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1876- r8go. xxxi XXXll LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. Arch. Civ. Prax. Archiv fiir die civilistische Praxis (Germany) . Arch. Jud. Archivo judiciario (Brazil). Ariz. Arizona Reports. Ark. Arkansas Reports. Asp. Marit. Cas. Aspinall's Maritime Cases. Atl. Atlantic Reporter, National Reporter System (United States). -

Report of the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts 2005

‘05 in Brief (listed chronologically) Pennsylvania’s minor court jurists, formerly called district judges, become known as magisterial district judges Report of the Chief Justice Ralph J. Administrative Office of Cappy forms the Pennsylvania Courts Interbranch Commis- sion for Gender, Racial 2005 and Ethnic Fairness to promote the equal application of the law for all citizens of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Supreme Court adopts Rules of Juvenile Procedure to establish for the first time uniform statewide procedures in juvenile courts that apply to all phases of delinquency cases that enter the state court system Justice Max Baer participates in “Changing Lives by Changing Systems: National Judicial Leadership Summit for Supreme Court of Pennsylvania the Protection of Chief Justice Ralph J. Cappy Children,” to work Justice Ronald D. Castille toward reforming the Justice Sandra Schultz Newman way abused and Justice Thomas G. Saylor neglected children’s Justice J. Michael Eakin cases proceed through Justice Max Baer the courts Justice Cynthia A. Baldwin Supreme Court issues order authorizing disciplinary pro- ceedings to be open to public review Pennsylvania begins development of a statewide education program for trial court judges who hear capital murder cases. The program, devel- oped with the Nevada- based National Judicial College, will be among the first of its kind in the nation. Kate Ford Elliott is elected president judge of Superior Court, becoming the first woman in Pennsyl- vania to lead an appellate court Title: (AOPC_Black.EPS) -

Research Guide

RESEARCH GUIDE Widener University School of Law www.law.widener.edu/Law-Library 4/2004 \ . New Jersey Legal Resources Most of the items in this research guide are free websites, since so Fantastic site with information and/or links to virtually much information now is on the Internet. However, the legal everything of importance in New Jersey government, plus more. researcher interested in New Jersey sho uld be aware that there are Here you will find links to such items as New Jersey Government two sections in the library where New Jersey print materials may be Publications on the W eb, Legislative Histories and even a link found: for Ask a Librarian. ! In the State Section which begins in aisle 30 on the 2nd floor. New Jersey State Law Library Items in the state section have call numbers beginning with KF, plus www.njstatelib.org the first initial of the state. Thus, New Jersey materials will be found Has good research guides, links to New Jersey Information and starting at KFN. Among the most frequently used of these items easy access to legislative histories from 1998 forward. Call for are: assistance with legislative histories prior to that time (609-292- 6230). – New Jersey Statutes Annotated (NJSA) - KFN1830.A42. – New Jersey Administrative Code - KFN1835 1995 New Jersey H istorical Documents – New Jersey Register - KFN1835 1969 www .state.nj.us/njfacts/njdocs.htm – New Jersey Digest - KFN1857.W4 – New Jersey Practice - KFN1880 .N47 County and Municipal Websites – New Jersey Forms - KFN1868 .N45 www .state.nj.us/localgov.htm ! In the U.S. -

Research Guide

Research Guide FINDING CASES I. HOW TO FIND A CASE WHEN YOU KNOW THE CITATION A. DECIPHERING LEGAL CITATIONS 1. CASE CITATIONS A case citation includes: the names of the parties, the volume number of the case reporter, the abbreviated name of the reporter, the page number where the case can be found, and the year of the decision. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800 (1982). Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta = names of the parties 30 = volume number of the case reporter Cal. = abbreviated name of the case reporter, California Reports 3d = series number of the case reporter, California Reports 800 = page number of the case reporter (1982) = year of the decision 2. ABBREVIATIONS OF REPORTER NAMES The abbreviations used in citations can be deciphered by consulting: a. Prince’s Bieber Dictionary of Legal Abbreviations, 6th ed. (Ref. KF 246 .p74 2009) b. Black's Law Dictionary (Ref. KF 156 .B624 2009). This legal dictionary contains a table of abbreviations. Copies of Black's are located on dictionary stands throughout the library, as well as in the Reference Collection. 3. REPORTERS AND PARALLEL CITATIONS A case may be published in more than one reporter. Parallel citations indicate the different reporters publishing the same case. EXAMPLE: Reserve Insurance Co. v. Pisciotta, 30 Cal.3d 800, 180 Cal. Rptr. 628, 640 P.2d 764 (1982). 02/08/12 (Rev.) RG14 (OVER) This case will be found in three places: the "official" California Reports 3d (30 Cal. 3rd 800); and the two "unofficial" West reporters: the California Reporter (180 Cal. -

Supreme Court of Ohio Writing Manual Is the First Comprehensive Guide to Judicial Opinion Writing Published by the Court for Its Use

T S C of O WRITING MANUAL A Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing effective july 1, 2013 second edition Published for the Supreme Court of Ohio WRITING MANUAL A Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing MAUREEN O’CONNOR Chief Justice SHARON L. KENNEDY PATRICK F. FISCHER R. PATRICK DeWINE MICHAEL P. DONNELLY MELODY J. STEWART JENNIFER BRUNNER Justices STEPHANIE E. HESS Interim administrative Director The Supreme Court of Ohio Style Manual Committee HON. JUDITH ANN LANZINGER JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO Chair HON. TERRENCE O’DONNELL JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO HON. JUDITH L. FRENCH JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO STEVEN C. HOLLON ADMINISTRATIVE DIRECTOR, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO ARTHUR J. MARZIALE JR., Retired July 31, 2012 DIRECTOR OF LEGAL RESOURCES, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO SANDRA H. GROSKO REPORTER OF DECISIONS, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO RALPH W. PRESTON, Retired July 31, 2011 REPORTER OF DECISIONS, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO MARY BETH BEAZLEY ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF LAW AND DIRECTOR OF LEGAL WRITING, MORITZ COLLEGE OF LAW, THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY C. MICHAEL WALSH ADMINISTRATOR, NINTH APPELLATE DISTRICT The committee wishes to gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of editor Pam Wynsen of the Reporter’s Office, as well as the excellent formatting assistance of John VanNorman, Policy and Research Counsel to the Administrative Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...........................................................................................................................ix -

How to Locate a Case Using a Digest

Sacramento County Public Law Library 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 >> Home >> Law 101 DIGESTS How to Locate a Case Using a Digest The Law Library has two sets of West Digests in print format (now published by Thomson Reuters): Table of Contents The United States Supreme Court Digest, used to locate 1. How to Locate a Case Using United States Supreme Court cases, is located in Compact Topic and Key Number System in Shelving next to the Supreme Court Reporter, at KF 101 .1 Westlaw ...................................... 2 U55. Like all digests, each volume in the set is updated 2. Abbreviations and Locations of with pocket parts. Case Reporters ............................ 4 West’s California Digest, located in Row C-9 of Compact Shelving at KFC 57 .W47, is used to locate California Supreme Court and California Appellate Court cases. Digests are arranged alphabetically by topic. Examples of the approximately 400 topics are: Banks and Banking, Franchises, Insurance, Libel and Slander, Partnership, Fraud, and Criminal Law. Each topic is divided into subtopics known as "key numbers." A complete list of topic headings is available in the front of each digest volume. A complete list of key numbers is available at the beginning of each topic. A Quick Reference Guide to West Key Number System is available online west.thomson.com/documentation/westlaw/wlawdoc/wlres/keynmb06.pdf. Locate a topic and key number that interests you by scanning the list of topic headings and key numbers or by using the Descriptive Word Index at the end of each set of digests. -

Loislaw Case Coverage Federal Reporters

Loislaw Case Coverage Loislaw includes comprehensive coverage of cases and associated citations for the reporters and date ranges listed here (except as noted for the F. Supp and B.R. reporters) and select coverage of cases and associated citations for unofficial reporters not listed here or reporters outside of the date ranges we cover. Jurisdiction Court Reporter Citation Style Date Range Volumes Status Federal Reporters U.S. U.S. Supreme Court U.S. Reports U.S. 1754-present 1-present Official Supreme Court Reporter S.Ct. 1935-present 55-present Unofficial U.S. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F 3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F 2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. 7th Circuit Court of Appeals Federal Reporter, 2d F.2d 1924-1993 1-999 Unofficial Federal Reporter, 3d F.3d 1993-present 1-present Unofficial U.S. -

California Style Manual

CALIFORNIA STYLE MANUAL Fourth Edition A HANDBOOK OF LEGAL STYLE FOR CALIFORNIA COURTS AND LAWYERS By Edward W. Jessen Reporter of Decisions for the Supreme Court and Courts of Appeal .W4-23370-9 ©1942, 1961, 1977, 1986,2000 by the Supreme Court of California Page composition by Imagelnk, San Francisco Cover design by Side by Side Designs, San Francisco Editiorial preparation and manufacturing West Group, California's Official Legal Publisher FOREWORD For almost 60 years, the legal community of California has benefited from the publication of the California Style Manual. The manual provides a guide to standard legal style in the appellate courts, and benefits litigants and jurists alike by establishing a common stylistic base that permits read- ers to focus readily on substance rather than form. In the 14 years since publication of the third edition of the Style Manual, much has changed in the processes used for creating legal docu- ments. A personal computer on the desk is now the rule rather than the exception for most lawyers and judges. At the same time, the availability of diverse reference resources has expanded the ease and scope of research. This latest revision of the manual reflects and responds to many of the changes that the legal profession has experienced, while maintaining a steady hold on the practices that have served the courts and the profession so well. I extend my appreciation to the Reporter of Decisions and those who have assisted him in the task of revising this valuable reference tool. Ronald M. George Chief Justice of California iii SUPREME COURT APPROVAL To the Reporter of Decisions: Pursuant to the authority conferred on the Supreme Court of Cali- fornia by Government Code section 68902, the California Style Manual, Fourth Edition, as submitted to this court for review is approved and adopted as the official organ for the styles to be used in the publication of the Official Reports. -

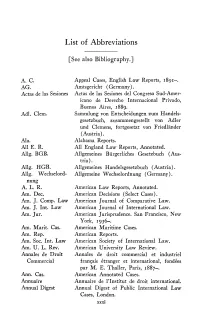

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations [See also Bibliography.] A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1891-. AG. Amtsgericht (Germany). Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, 188g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). Allg. W echselord- Allgemeine W echselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions (Select Cases). Am. J. Camp. Law American Journal of Comparative Law. Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Am. Soc. Int. Law American Society of International Law. Am. U. L. Rev. American University Law Review. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, 1887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. xxxi xxxn LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis Comp. lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r876- r8go. App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. -

TMLL Guide Chapter 7

CHAPTER 7 CASE LAW RESEARCH TABLE OF CONTENTS Case Law: Background Court Hierarchies and the Appellate Process Print Sources for Case Law Research Electronic Sources for Case Law Research Citators: Function and Formats Print Citators Electronic Citators Citation Format for Cases Highlights of Bluebook Form for Cases CASE LAW: BACKGROUND For the purpose of legal research the term “cases” or “case law” refers to opinions written by judges, usually on the appellate level, which resolve litigated disputes. In deciding cases, appellate judges base their reasoning on mandatory and persuasive legal authority, such as statutes, regulations, and previously decided cases. There are several points to keep in mind when conducting case research: • Opinions of the highest level appellate court of the jurisdiction are the most important mandatory authority. If the highest level court has ruled on a matter, that ruling binds any intermediate level appellate or trial courts in the jurisdiction. If the highest court has not ruled, the rulings of intermediate level courts are the best authority which can be found, but they do not bind the higher level court in any subsequent proceeding. • When researching, it is usually most efficient to seek out and read the most recent cases first and work your way back. The most recent cases will: a) reflect the current state of the law and b) contain citations to, and discussions of, earlier relevant cases. • Remember that the short summary of a case (known as the syllabus) and the headnotes which precede the court’s opinion are provided by the editors of the reporter, and do not constitute part of the actual opinion, although they often quote or paraphrase its actual text. -

TMLL Guide Chapter 9

CHAPTER 9 RESEARCHING A MARYLAND LAW PROBLEM TABLE OF CONTENTS Maryland Government Maryland Constitution Maryland Legislation Maryland Courts Maryland Court Rules Maryland Administrative Materials Maryland Local Law Baltimore City Materials Maryland Practice Materials MARYLAND GOVERNMENT Maryland government is comprised of three branches: the executive, legislative, and judicial. The executive is led by the governor of Maryland. Legislative power is vested with the General Assembly. The General Assembly has two chambers: the House of Delegates and the Senate. The judiciary consists of the Court of Appeals (the state’s highest appellate court); the Court of Special Appeals (the intermediate appellate court); circuit courts (trial courts of general jurisdiction); district courts, and the Orphan’s Court. For more information on the structure Maryland state and local government, see the Maryland Manual On-Line. MARYLAND CONSTITUTION The Maryland Constitution establishes the powers and structure of state government and guarantees certain fundamental rights. Maryland has had four constitutions in its history. The current Maryland Constitution is the 1867 constitution albeit with significant amendments. An excellent resource on the Maryland Constitution is The Maryland State Constitution by Dan Friedman. It is available online (EBSCO eBook Collection, login required) and in print (Law Library, Level 2, KFM1601 1867.A6 F747 2011). The Maryland Constitution begins with a Declaration of Rights, currently consisting of 47 articles, that describes and protects certain fundamental human rights. The Declaration of Rights protects some rights also found in the U.S. Constitution such as freedom of speech. However, Maryland’s Declaration of Rights also provides, in some instances, greater protections than those found in the U.S. -

New Jersey Practice Materials: a Selective Annotated Bibliography

New Jersey Practice Materials: A Selective Annotated Bibliography TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ... ............................................ 5 G eneral Publications ......................................... 6 General Reference and Research Sources ...................... 6 Statutory Sources ........................................ 7 Session Law s ............................................ 9 Legislation and Legislative Information ...................... 10 C ase R eports ........................................... 12 Free Case Law and Judicial Information on the Internet ......... 14 D igests and Citators ..................................... 15 C ourt R ules ............................................ 17 Attorney General Opinions ................................ 18 Executive and Administrative Materials ...................... 18 Administrative Rules and Regulations ....................... 18 Administrative Decisions ................................. 19 Ethics Codes and Opinions ................................ 20 D irectories ............................................. 21 Periodicals .... ............................................ 22 A cadem ic Journals ...................................... 22 Bar Association Publications .............................. 24 N ew spapers ............................................ 25 Topical Journals and Newsletters ........................... 26 Internet Resources .......................................... 27 State H om e Page ........................................ 27 Government Offices ....................................