TMLL Guide Chapter 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of Vermont- Nathaniel West V

West v. Holmes, 26 Vt. 530 (1854) contract 26 Vt. 530 Gaming and Lotteries Supreme Court of Vermont. Stakeholders NATHANIEL WEST All wagers are illegal; and a party making such a v. wager and depositing it in the hands of a GEORGE R. HOLMES. stakeholder may, by demanding it back at any time before it is paid over to the winner by his April Term, 1854. express or implied assent, entitle himself to recover back the money or other thing, and the stakeholder will be liable if he subsequently pays the winner. West Headnotes (4) 1 Cases that cite this headnote [1] Contracts Recovery of money paid or property transferred Gaming and Lotteries [4] Contracts Persons entitled to recover Recovery of money paid or property transferred At common law, the parties to a gaming Gaming and Lotteries transaction stand in pari delicto, and money lost Particular Contexts and paid over cannot be recovered. Money lost upon an ordinary wager does not come within C.S. 1850, c. 110, § 12, which 1 Cases that cite this headnote provides for the recovery of money lost at a “game or sport.” Cases that cite this headnote [2] Contracts Recovery of money paid or property transferred Gaming and Lotteries Persons liable and extent of liability Where a stakeholder pays the money over to the **1 *531 ASSUMPSIT for money had and received. winner, after the other party has demanded it of him, the loser may pursue the money into the Plea, the general issue, and trial by the court. winner’s hands, or into the hands of any person to whom it comes. -

A Handbook of Citation Form for Law Clerks at the Appellate Courts of the State of Hawai#I

A HANDBOOK OF CITATION FORM FOR LAW CLERKS AT THE APPELLATE COURTS OF THE STATE OF HAWAI ###I 2008 Edition Hawai #i State Judiciary 417 South King Street Honolulu, HI 96813 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. CASES............................................ .................... 2 A. Basic Citation Forms ............................................... 2 1. Hawai ###i Courts ............................................. 2 a. HAWAI #I SUPREME COURT ............................... 2 i. Pre-statehood cases .............................. 2 ii. Official Hawai #i Reports (volumes 1-75) ............. 3 iii. West Publishing Company Volumes (after 75 Haw.) . 3 b. INTERMEDIATE COURT OF APPEALS ........................ 3 i. Official Hawai #i Appellate Reports (volumes 1-10) . 3 ii. West Publishing Company Volumes (after 10 Haw. App.) .............................................. 3 2. Federal Courts ............................................. 4 a. UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT ......................... 4 b. UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS ...................... 4 c. DISTRICT COURTS ...................................... 4 3. Other State Courts .......................................... 4 B. Case Names ................................................... 4 1. Case Names in Textual Sentences .............................. 5 a. ACTIONS AND PARTIES CITED ............................ 5 b. PROCEDURAL PHRASES ................................. 5 c. ABBREVIATIONS ....................................... 5 i. in textual sentences .............................. 5 ii. business -

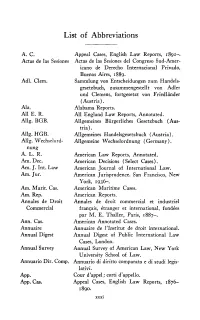

List of Abbreviations

List of Abbreviations A. C. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, r8gr-. Aetas de las Sesiones Aetas de las Sesiones del Congreso Sud-Amer icano de Derecho Internacional Privado, Buenos Aires, r88g. Adl. Clem. Sammlung von Entscheidungen zum Handels gesetzbuch, zusammengestellt von Adler und Clemens, fortgesetzt von Friedlander (Austria). Ala. Alabama Reports. All E. R. All England Law Reports, Annotated. Allg. BGB. Allgemeines Biirgerliches Gesetzbuch (Aus- tria). Allg. HGB. Allgemeines Handelsgesetzbuch (Austria). All g. W echselord- Allgemeine Wechselordnung (Germany). nung A. L. R. American Law Reports, Annotated. Am. Dec. American Decisions ( Select Cases) . Am. J. Int. Law American Journal of International Law. Am. Jur. American Jurisprudence. San Francisco, New York, 1936-. Am. Marit. Cas. American Maritime Cases. Am. Rep. American Reports. Annales de Droit Annales de droit commercial et industriel Commercial fran~ais, etranger et international, fondees par M. E. Thaller, Paris, r887-. Ann. Cas. American Annotated Cases. Annuaire Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international. Annual Digest Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, London. Annual Survey Annual Survey of American Law, New York University School of Law. Annuario Dir. Camp. Annuario di diritto comparato e di studi legis lativi. App. Cour d'appel; corti d'appello. App. Cas. Appeal Cases, English Law Reports, 1876- r8go. xxxi XXXll LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS App. D.C. Appeal Cases, District of Columbia. App. Div. New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division Reports. Arch. Civ. Prax. Archiv fiir die civilistische Praxis (Germany) . Arch. Jud. Archivo judiciario (Brazil). Ariz. Arizona Reports. Ark. Arkansas Reports. Asp. Marit. Cas. Aspinall's Maritime Cases. Atl. Atlantic Reporter, National Reporter System (United States). -

Teaching Rule Synthesis with Real Cases

245 Teaching Rule Synthesis with Real Cases Paul Figley Rule synthesis is the process of integrating a rule or principle from several cases.1 It is a skill attorneys and judges use on a daily basis to formulate effective arguments, develop jurisprudence, and anticipate future problems.2 Teaching new law students how to synthesize rules is a critical component in training them to think like lawyers.3 While rule synthesis is normally taught in legal writing classes, it has application throughout the law school experience. Academic support programs may teach it to students even before their first official law school class.4 Many professors convey analytical lawyering skills, including rule synthesis, in their 1. Richard K. Neumann, Jr. & Sheila Simon, Legal Writing 55 (Aspen 2008) (“Synthesis is the binding together of several opinions into a whole that stands for a rule or an expression of policy.”). 2. Jane Kent Gionfriddo, Thinking Like A Lawyer: The Heuristics of Case Synthesis, 40 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 1, 7 (2007). On a more pedestrian level, good litigators develop the facility to read the cases cited by an opponent in support of its proposed rule, and synthesize from them a different, more credible rule that undermines the opponent’s case. 3. See id. at 7; see also Kurt M. Saunders & Linda Levine, Learning to Think Like A Lawyer, 29 U.S.F. L. Rev. 121, 125 (1994). 4. See Sonia Bychkov Green, Maureen Straub Kordesh & Julie M. Spanbauer, Sailing Against the Wind: How A Pre-Admission Program Can Prepare at-Risk Students for Success in the Journey Through Law School and Beyond, 39 U. -

Principles of Administrative Law 1

CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD PRINCIPLES OF LAW SERIES Professor Paul Dobson Visiting Professor at Anglia Polytechnic University Professor Nigel Gravells Professor of English Law, Nottingham University Professor Phillip Kenny Professor and Head of the Law School, Northumbria University Professor Richard Kidner Professor and Head of the Law Department, University of Wales, Aberystwyth In order to ensure that the material presented by each title maintains the necessary balance between thoroughness in content and accessibility in arrangement, each title in the series has been read and approved by an independent specialist under the aegis of the Editorial Board. The Editorial Board oversees the development of the series as a whole, ensuring a conformity in all these vital aspects. David Stott, LLB, LLM Deputy Head, Anglia Law School Anglia Polytechnic University Alexandra Felix, LLB, LLM Lecturer in Law, Anglia Law School Anglia Polytechnic University CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney First published in Great Britain 1997 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX. Telephone: 0171-278 8000 Facsimile: 0171-278 8080 e-mail: [email protected] Visit our Home Page on http://www.cavendishpublishing.com © Stott, D and Felix, A 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. -

Towards an Effective Class Action Model for European Consumers: Lessons Learnt from Israel

Towards an Effective Class Action Model for European Consumers: Lessons Learnt from Israel A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ariel Flavian Brunel University School of Law September 2012 Towards an Effective Class Action Model for European Consumers: Lessons Learnt from Israel Ariel Flavian The class action is an important instrument for the enforcement of consumers' rights, particularly in personal actions for low sums known as Negative Expected Value (NEV) suits. Collective redress actions transform NEV suits into Positive Expected Value suits using economies of scale by the aggregation of smaller actions into a single legal action which is economically worthwhile pursuing. Collective redress promotes adherence to the law, deters illegal actions and furthers public interests. Collective redress also helps in the management of multiple cases in court. The introduction of a new class action model in Israel has proven to be very workable in the sense that it has improved access to justice, albeit that this system currently suffers from over-use, referred to in this work as the "flood problem". The purpose of this research is to introduce a class action model which brings with it the advantages of the Israeli model, as well as improvements upon it so as to promote consumer confidence in low figure transactions by individuals with large, powerful companies. The new model suggested in this work relies on the opt-out mechanism, monitored by regulatory bodies through public regulation or by private regulators. The reliance on the supremacy of public enforcement and follow-on actions over private stand-alone actions should make the system of collective redress more efficient than the current Israeli model, reducing the risk of a flood of actions whilst at the same time improving access to justice for large groups of claimants. -

Principles of Tort Law Rachael Mulheron Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-72764-8 — Principles of Tort Law Rachael Mulheron Frontmatter More Information Principles of Tort Law Presenting the law of Tort as a body of principles, this authoritative textbook leads students to an incisive and clear understanding of the subject. Each tort is carefully structured and examined within a consistent analytical framework that guides students through its preconditions, elements, defences, and remedies. Clear summaries and comparisons accompany the detailed exposition, and further support is provided by numerous diagrams and tables, which clarify complex aspects of the law. Critical discussion of legal judgments encourages students to develop strong analytical and case-reading skills, while key reform pro posals and leading cases from other jurisdictions illustrate different potential solutions to conun- drums in Tort law. A rich companion website, featuring semesterly updates, and ten additional chapters and sections on more advanced areas of Tort law, completes the learning package. Written speciically for students, the text is also ideal for practitioners, litigants, policy-makers, and law reformers seeking a comprehensive and accurate understanding of the law. Rachael Mulheron is Professor of Tort Law and Civil Justice at the School of Law, Queen Mary University of London, where she has taught since 2004. Her principal ields of academic research concern Tort law and class actions jurisprudence. She publishes regularly in both areas, and has frequently assisted law reform commissions, government departments, and law irms on Tort-related and collective redress- related matters. Professor Mulheron also undertakes extensive law reform work, previously as a member of the Civil Justice Council of England and Wales, and now as Research Consultant for that body. -

710 ATLANTIC REPORTER, 2D SERIES N. J. Suspensions. As

450 N. J. 710 ATLANTIC REPORTER, 2d SERIES suspensions. As modified, the judgment of of funding public schools, students chal- the Appellate Division is affirmed. lenged constitutionality of funding plan de- veloped by state in response to judicial For modification and affirmance—Chief mandate. The Supreme Court found plan Justice PORITZ and Justices HANDLER, facially constitutional but unconstitutional as POLLOCK, O’HERN, GARIBALDI, STEIN applied to special needs districts (SNDs), and COLEMAN—7. ordered parity funding as interim remedy, Opposed–none. and remanded for fact-finding hearings, 149 N.J. 145, 693 A.2d 417. Following conduct , of fact-finding hearings by the Superior Court, Chancery Division, King, J., and sub- mission of Report and Recommendation 153 N.J. 480 with respect thereto, the Supreme Court, S 480Raymond ABBOTT, a minor, by his Handler, J., held that: (1) elementary school Guardian Ad Litem, Frances ABBOTT; reform plan proposed by state education Arlene Figueroa, Frances Figueroa, and finance officials comported substantially Hector Figueroa, Orlando Figueroa, and with statutory and regulaStory481 policies de- Vivian Figueroa, minors, by their fining constitutional guarantee of thorough Guardian Ad Litem, Blanca Figueroa; and efficient education; (2) full-day kinder- Michael Hadley, a minor, by his Guard- garten plan comported substantially with ian Ad Litem, Lola Moore; Henry Ste- same statutory and regulatory policies and vens, Jr., a minor, by his Guardian Ad was essential to satisfaction of constitutional Litem, -

Report of the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts 2005

‘05 in Brief (listed chronologically) Pennsylvania’s minor court jurists, formerly called district judges, become known as magisterial district judges Report of the Chief Justice Ralph J. Administrative Office of Cappy forms the Pennsylvania Courts Interbranch Commis- sion for Gender, Racial 2005 and Ethnic Fairness to promote the equal application of the law for all citizens of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Supreme Court adopts Rules of Juvenile Procedure to establish for the first time uniform statewide procedures in juvenile courts that apply to all phases of delinquency cases that enter the state court system Justice Max Baer participates in “Changing Lives by Changing Systems: National Judicial Leadership Summit for Supreme Court of Pennsylvania the Protection of Chief Justice Ralph J. Cappy Children,” to work Justice Ronald D. Castille toward reforming the Justice Sandra Schultz Newman way abused and Justice Thomas G. Saylor neglected children’s Justice J. Michael Eakin cases proceed through Justice Max Baer the courts Justice Cynthia A. Baldwin Supreme Court issues order authorizing disciplinary pro- ceedings to be open to public review Pennsylvania begins development of a statewide education program for trial court judges who hear capital murder cases. The program, devel- oped with the Nevada- based National Judicial College, will be among the first of its kind in the nation. Kate Ford Elliott is elected president judge of Superior Court, becoming the first woman in Pennsyl- vania to lead an appellate court Title: (AOPC_Black.EPS) -

Fedresourcestutorial.Pdf

Guide to Federal Research Resources at Westminster Law Library (WLL) Revised 08/31/2011 A. United States Code – Level 3 KF62 2000.A2: The United States Code (USC) is the official compilation of federal statutes published by the Government Printing Office. It is arranged by subject into fifty chapters, or titles. The USC is republished every six years and includes yearly updates (separately bound supplements). It is the preferred resource for citing statutes in court documents and law review articles. Each statute entry is followed by its legislative history, including when it was enacted and amended. In addition to the tables of contents and chapters at the front of each volume, use the General Indexes and the Tables volumes that follow Title 50 to locate statutes on a particular topic. Relevant libguide: Federal Statutes. • Click and review Publication of Federal Statutes, Finding Statutes, and Updating Statutory Research tabs. B. United States Code Annotated - Level 3 KF62.5 .W45: Like the USC, West’s United States Code Annotated (USCA) is a compilation of federal statutes. It also includes indexes and table volumes at the end of the set to assist navigation. The USCA is updated more frequently than the USC, with smaller, integrated supplement volumes and, most importantly, pocket parts at the back of each book. Always check the pocket part for updates. The USCA is useful for research because the annotations include historical notes and cross-references to cases, regulations, law reviews and other secondary sources. LexisNexis has a similar set of annotated statutes titled “United States Code Service” (USCS), which Westminster Law Library does not own in print. -

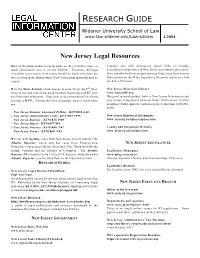

Research Guide

RESEARCH GUIDE Widener University School of Law www.law.widener.edu/Law-Library 4/2004 \ . New Jersey Legal Resources Most of the items in this research guide are free websites, since so Fantastic site with information and/or links to virtually much information now is on the Internet. However, the legal everything of importance in New Jersey government, plus more. researcher interested in New Jersey sho uld be aware that there are Here you will find links to such items as New Jersey Government two sections in the library where New Jersey print materials may be Publications on the W eb, Legislative Histories and even a link found: for Ask a Librarian. ! In the State Section which begins in aisle 30 on the 2nd floor. New Jersey State Law Library Items in the state section have call numbers beginning with KF, plus www.njstatelib.org the first initial of the state. Thus, New Jersey materials will be found Has good research guides, links to New Jersey Information and starting at KFN. Among the most frequently used of these items easy access to legislative histories from 1998 forward. Call for are: assistance with legislative histories prior to that time (609-292- 6230). – New Jersey Statutes Annotated (NJSA) - KFN1830.A42. – New Jersey Administrative Code - KFN1835 1995 New Jersey H istorical Documents – New Jersey Register - KFN1835 1969 www .state.nj.us/njfacts/njdocs.htm – New Jersey Digest - KFN1857.W4 – New Jersey Practice - KFN1880 .N47 County and Municipal Websites – New Jersey Forms - KFN1868 .N45 www .state.nj.us/localgov.htm ! In the U.S. -

Current Sources for Federal Court Decisions Prepared by Frank G

Current Sources for Federal Court Decisions Prepared by Frank G. Houdek, January 2009 Level of Court Name of Court Print Source Westlaw* LexisNexis* Internet TRIAL District Court Federal Supplement, 1932 •Dist. Court Cases—after •US Dist. Court Cases, U.S. Court Links (can select (e.g., S.D. Ill.) to date (F. Supp., F. 1944 Combined by type of court & Supp. 2d) •Dist. Court Cases—by •Dist. Court Cases—by location) circuit circuit http://www.uscourts.gov •Dist Court Cases—by •Dist. Court Cases—by state /courtlinks/ state/territory Federal Rules Decisions, 1938 to date (F.R.D.) Bankruptcy Court Bankruptcy Reporter, •Bankruptcy Cases—by US Bankruptcy Court Cases U.S. Court Links (can select 1979 to date (B.R.) circuit by type of court & location) •Bankruptcy Courts http://www.uscourts.gov /courtlinks/ INTERMEDIATE Courts of Appeals (e.g., Federal Reporter, 1891 to •US Courts of Appeals •US Courts of Appeals U.S. Court Links (can select APPELLATE 7th Cir., D.C. Cir.) date (F., F.2d, F.3d) Cases Cases, Combined by type of court & location) [formerly Circuit •Courts of Appeals •Circuit Court Cases—by http://www.uscourts.gov Courts of Appeals] Cases—by circuit circuit /courtlinks/ Federal Appendix, 2001 to US Courts of Appeals date (F. App’x) Cases, Unreported HIGHEST Supreme Court •United States Reports, All US Supreme Court US Supreme Court Cases, •Supreme Court of the APPELLATE 1790 to date (U.S.) Cases Lawyers’ Edition United States, •Supreme Court Reporter, 1991–present, 1882 to date (S. Ct.) http://www.supremecour •United States Supreme tus.gov/opinions/opinion Court Reports, s.html Lawyers’ Edition, 1790 •HeinOnline, vol.